|

|

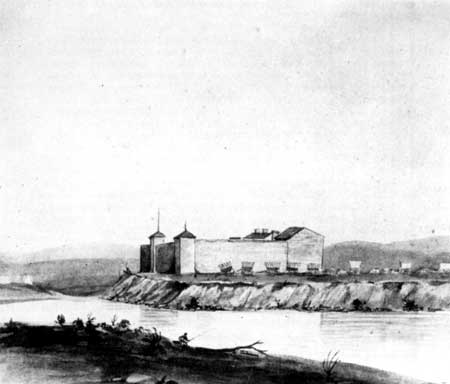

Contemporary sketch of Fort Laramie in 1849, made

by an unknown artist, possibly William Tappan, who accompanied the

Regiment of Mounted Riflemen under Colonel Loring. This was the

fur-traders' "Fort John," replaced subsequently by Army structures.

Courtesy Wisconsin Stale Historical Society.

|

Section III

While the Mounted Riflemen were still making furious

preparations for their strenuous assignment, the first wave of emigrants

was rolling westward from the border settlements. A correspondent for

the Missouri Republican wrote from Fort Kearny, on May 18:

. . . the inundation of gold diggers is upon us. The

first specimen, with a large pick-axe over his shoulder, a long rifle in

his hand, and two revolvers and a bowie knife stuck in his belt, made

his appearance here a week ago last Sunday . . . Up to this morning four

hundred and seventy-six wagons have gone past this point; and this is

but the advance guard.

Every state, and I presume almost every town and

county in the United States, is now represented in this part of the

world. Wagons of all patterns, sizes and descriptions, drawn by bulls,

cows, oxen, jack asses, mules and horses, are daily seen rolling along

towards the Pacific, guarded by walking arsenals . . . [28]

Endless columns of white-topped wagons crawled like

gigantic ants along both sides of the river Platte, jockeying for

position, milling and piling up at the dangerous fords. The advance

guard of a multitude variously estimated at 30,000 to 50,000 souls was

spearheading the advance upon Fort Laramie. After crossing the South

Platte, the emigrants came successively upon the famous landmarks along

the south bank of the North Platte—Ash Hollow, Courthouse Rock,

Chimney Rock, Scotts Bluffs. At the latter point, some fifty miles east

of Fort Laramie, was stationed a trader and blacksmith named Robidoux,

the only white settler in sight between Fort Kearny and Fort Laramie.

Otherwise, the Valley of the North Platte was given over to buffalo

herds, skulking Sioux, wolves, prairie dogs, and mirages.

According to eastbound Mormon observers, the first

Argonauts had reached Laramie Fork by May 22. [29] The first identifiable traveller to reach

the trading post, about May 28, was an Irish citizen, Kelly by name, who

was not impressed:

. . . my glowing fancy vanished before the wreched

reality—a miserable, cracked, dilapidated, adobe, quadrangular

enclosure, with a wall about twelve feet high, three sides of which were

shedded down as stores and workshops, the fourth, or front, having a

two-story erection, with a projecting balcony, for hurling projectiles

or hot water on the foe, propped all around on the outside with beams of

timber, which an enemy had only to kick away and down would come the

whole structure.

I found Mr. Husband, the manager, or governor as he

is styled, a most obliging, intelligent, and communicative person . . .

we made use of the forge to tighten our wheel tyres, and make other

small repairs . . . There were some Indians of the Sioux tribe about the

fort trading while we were there . . . rattling away with great

volubility . . . There is besides the governor, a superintendent and ten

men employed in stowing and packing robes and skins. [30]

(Bruce Husband, who was to figure in the sale of Fort

Laramie, had been left behind in charge by Maj. Andrew Drips, who had

left in the spring to conduct his buffalo robes to St. Louis. Little is

known of him, but we may infer that he was a full-blown "mountain man"

of the old time trade, who viewed with distaste the manner in which

events were rushing toward him. In a postscript to his letter of May 24

at "Fort John" to Andrew Drips, he prophesies: "I don't think I shall go

back to St. Louis or even to the states again.") [31]

William Johnston's company, on May 29, found the

Laramie low enough to ford comfortably, then camped at the forks, and

walked up to the stockade, which he describes with more fervor than

Kelly:

. . . Besides a private entrance, there was a large

one with a gate which faced toward the angles of the rivers. Over the

entrance was a tower with loopholes, and at two of the angles,

diagonally opposite each other, were bastions, also perforated with

loopholes, through which all sides of the fort could be defended. Two

brass swivels were mounted at the entrance . . . Fort Laramie is the

principal trading post of the American Fur Company . . . It is soon,

however, to pass into possession of the United States . . .

It seems to be a custom of emigrants on arriving here

to lighten up, and Fort Laramie is made a dumping place for all that can

be spared . . .

We observed quite a number of Indian women, the wives

of traders and trappers, and their children, lounging the fort or

sitting in the doorways . . . We could not escape the conviction that

soap and water were scarce . . . or . . . greatly neglected. [32]

By June 12 the banks of the Laramie were running full

and causing trouble. In George P. Burrall's diary we find:

. . . A good many teams crossing here. Had to raise

our wagon boxes to keep the water from running in. Stopped at the fort

one hour. No troops there. One trader and a blacksmith shop. Good many

wagons repairing here and some thrown away. [33]

Alonzo Delano, who also appeared on the scene on June

12, was a more useful observer:

. . . A drive of seven miles from our encampment

brought us to Laramie River, where we found a multitude of teams,

waiting their turn to cross a swift and not safe current. It became

necessary to raise our wagon boxes about six inches, in order to prevent

the water flowing in and wetting our provisions . . . Fort Laramie is

simply a trading post, standing about a mile above the ford . . . Its

neat white washed walls presented a welcome sight to us . . . and the

motley crowed of emigrants, with their array of wagons, cattle, horses

and mules, gave a pleasant appearance of life and animation . . .

Around the fort were many wagons, which had been sold

or abandoned . . . Here was a deposit for letters to be sent to the

States . . . on which the writers paid twenty-five cents . . . [34]

On the following day, June 13, Joseph Hackney found

the river still up and very swift:

. . . went 4 miles to larime river we had to raise

our wagon beds up and put block under them to raise them above the water

. . . [some] teams got into deep water and wet all of their load . . .

fort larime is one mile from the river it is built after the fashion of

the mexican's ranch theiere is no troops hear yet but they expect them

in a few days . . . [35]

Two valuable informants appear on June 14 to reflect

the crescendo-like rush of the migration. Both mention the difficult

ford and the deserted Fort Platte. Joseph Wood writes:

. . . found the water in Laramie's Fk so deep as to

cover the fore wheels of our Wagon . . . On our right from here; was the

bare mud walls of an old deserted fort and on our left & one mile up

Laramie's fork was the Fort of that name. It present quite an imposing

appearance as you approach it & was surrounded with emigrants, who

were gratifying their long pent up curiosity . . . The fort was nearly

deserted by those who propertly belong to it . . . they being gone to

the States with hides and furs. Emigrants were throwing away freight

which they had retained with the hope of selling here to advantage . . .

I went to view a spot where an Indian corpse had been pulled down from a

tree. [36]

Vincent Geiger found Mr. Husband still head man at

the Fort:

. . . Several Indian squaws with half breed children

were found there, and a number of Mexicans. There is nothing enticing or

pleasing about the place. They were destitute of all articles of trade

except jerked buffalo meat. We found a young emigrant who had been

accidentally shot in the thigh . . . There were no Indians about, they

having gone to war with the Crows. [37]

On June 15 Isaac Wistar and a companion, scouting in

advance of their train, attempted to elude Indians on the prowl for

stray scalps. Writes Wistar:

. . . We hoped to put Laramie's Fork between us and

those undesirable acquaintances, but on reaching it, found it swelled to

a turbulent river . . . cold as ice and with a rushing current full of

slippery, round boulders . . .

. . . We both stripped for swimming, and securely

fastened clothes and arms to the saddles, tying the ammunition on our

heads . . . I jumped my horse off the vertical bank, found swimming

water almost immediately, and quartering down stream, made the opposite

bank some 100 yards below . . .

Walking up to the adobe Fort, "a rough and

primitive-looking place," Wistar found countless dilapidated wagons

standing about, some broken up for material for pack saddles. Its

inhabitants consisted of a "clerk" and six or eight others, all French

or half-breeds. He continues:

. . . we lounged round the fort, looking at the

trading and store rooms, fur presses and other arrangements novel to us

. . . when, being assured . . . that Indians would not molest us in the

sight of the fort, . . . we moved across the level plain to the Platte .

. . and had an opportune success in killing a young antelope.

Wistar is the last recorded eyewitness of the adobe

Fort in its role as a sleepy trading post, for the next day, June 16,

Major Sanderson and his company of Mounted Riflemen arrived on the

scene. The journal continues:

A man and several head of stock were drowned last

night from a large emigrant train, while crossing Laramie's Fork.

Tonight our own train came rolling with men and teams well battered by .

. . forced marches . . . The Fork having gone down very much, all hands

went right to work blocking up wagon beds, doubling teams, lashing fast

cargoes, etc. and, after some hard work, crossed everything without

loss. Later a U. S. Government train of one company of dragoons under

Major Saunders, with wagons, stock and belongings, arrived and crossed,

the stream having still further fallen. Their business is to take charge

of the fort for a government post. [38]

E. B. Farnham was another eyewitness of events on

this crucial day:

Started at sunrise. Came to Larimie creek, one mile

from the fort, that we had to ford . . . Other trains that had gotten

there earlier had to take their turn, and there was quite a number. Our

hearts were light in anticipation of getting to the fort. Here among

this multitude all was excitement to get across. Something was ahead, it

seemed like a gala day, as a convention . . . Then the sound of the

cannon, that was fired to greet the arrival of Major Sanderson, came

booming from the fort . . .

. . . We found [Fort Laramie] to be a place of no

very imposing structure and appearance . . . The inhabitants of this

fort consist at this time of about 18 or 20 traders and trappers,

regular old 'hosses' as they term themselves. Some of these have squaw

wives living here at the fort and are a rough, outlandish, whisky

drinking, looking set . . . Major Sanderson is to take possession . . .

[39]

Company E, now on the scene, included 58 enlisted

men, 5 officers. Besides Sanderson and Woodbury, these were Maj. S. P.

Moore, Surgeon (later Surgeon General of the Confederate Army); Capt.

Thomas Duncan (to become a Brigadier General during the Civil War); and

Capt. George McLane (brevetted for gallantry in the Mexican War, killed

in battle against Indians in 1860), as Adjutant and Quartermaster. [40]

The emigrants who have testified thus far all

followed the south bank of the Platte. A respectable number, however,

"jumped off" from Council Bluffs, and thence followed the north bank of

the Platte as far as Fort Laramie, where they finally crossed. The

Platte was, of course, a much more formidable stream than the Laramie

and, during flood stage, could not be crossed except by a precarious

ferryboat, apparently rigged up and operated by the traders. Isaac

Foster was among those who pulled up, on the 15th, on the left bank:

. . . one man was drowned, they advised us not to

attempt to swim the river, which is 200 yards in width; saw an Indian;

young one, in the top of a tree, buried, being wrapped in a blanket and

skin.

Saturday, 16th—Crossed the Platte over to Fort

Laramie . . . we paid $1.00 per wagon for the use of the boat to ferry

us over . . . there seems to be about 50 persons residing [at the fort],

and provisions without money and without price; as you pass along you

see piles of bacon and hard bread thrown by the side of the road; about

50 wagons left here, and many burned and the irons left; trunks,

clothes, boots and shoes, left by the hundred, spades, picks, guns and

all other fixings for a California trip . . . here in the junction of

the roads hundreds of teams are coming together . . . here came up a

company of U. S. dragoons, two companies having passed on before, and a

company of infantry behind the troops for the protection of the

emigrants; I learned that one company is to be stationed here abouts;

here we enter the Black Hills . . . [41]

Lieutenant Woodbury wasted no time in getting down to

brass tacks with the Fur Company management. Although formal

arrangements were not concluded for another ten days, and although none

of the principals have recorded the event, it seems clear that Woodbury

and Husband talked things over right away, and a deal was agreed upon;

for, writes eyewitness Wistar, on June 17, "the stars and stripes went

up on the fort this morning, receiving our hearty cheers." The alacrity

of the Company at the prospect of a cash offer is testimonial enough to

the decrepit state of the fur trade in 1849.

Wistar continues,

. . . Since we can get no more animals and there is

no other inhabited place nearer than Fort Hall, many hundred miles

distant, it is evident we must carry our wagons through, or do worse; so

we conclude to nurse our failing teams and make the best of it . . . and

we still farther reduced our [load] to the estimated weight of about 200

pounds per man. This work, with washing, mending, reloading and cooking

for some days ahead, occupied all hands today, and tomorrow bright and

early, away we go. [42]

Farnham's train also laid over on the 17th:

This day we lay by and while we were here we had the

tires to our wagons cut and re-set . . . One of our men took a faint

spell while walking around the fort . . . took him into the avenue of

the fort where there was a shade and he soon recovered. The weather was

sultry hot. I saw a man that was wounded by a comrade . . . even the man

that shot him deserted him and . . . stole one of his blankets . . .

Another man that was sick and reduced to a mere living frame, was laying

in a wagon near the fort. His entire company had deserted him. However,

they left him the wagon to lay in and provisions of two barrels of

liquor; these they could not take along with them. [43]

Fort Laramie marked the end of the High Plains, the

beginning of the long upgrade haul to the Rocky Mountains. It was the

end of the line for the sick, the tired, the downhearted. Tempers,

frayed by weeks of toil, mud, dust, sunglare, and Indian alarms,

snapped. Amos Steck, on June 19, tried to buy ox-shoes and was asked an

exhorbitant price by the traders, "though there was a blacksmith shop

there and a copious abundance of iron. Such imposition we could not

stand. Camped one mile beyond. . . ." [44]

Sterling Clark was among those who, fed up with a clumsy, temperamental

wagon, discarded it and the bulk of his earthly possessions at this

point, and pinned his faith on a pack mule. Packing problems, coupled

with diarrhea, continued to plague him. [45] Another kind of annoyance cropped up to

bother Lucius Fairchild of the Madison (Wisconsin) Star Company. This

was the advent of a contingent of Mounted Riflemen under Col. William

Loring, headed for Oregon. He writes, "The U. S. Train has been near us

every since they struck this road and always in the way, in fact they

were the most perfect nusance on the whole road." Fairchild made it to

the Fort just ahead of the Riflemen, pausing only long enough to

observe: "Fort Laramie is built of mud & stone in the form of a

Hollow square." At Green River his luck ran out and he was "taken with

the Mountain Fever . . . and lay nearly 2 weeks in the wagon being

draged over a most awful road." [46]

The arrival of the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen at

Laramie Creek at 2 p.m. on the 22d of June has been officially and dully

recorded by Maj. Osborne Cross, Quartermaster:

. . . It was excessively warm and dusty . . .

There are no trees about the fort to protect it from

the rays of the sun, which are reflected from the surrounding hills. It

is by no means a handsome location . . . The hunting at this place has

generally been very good and is its only attraction. Even this has been

greatly diminished since the emigrants have made it the great

thoroughfare to Oregon and California . . .

. . . This was to be a resting place for us for a few

days . . . From the first of June our journey was made very unpleasant

by constant rains which made the roads very heavy and the hauling

extremely hard. Wood is not to be procured from the time you leave Fort

Kearny until you arrive at this place. Nothing is to be seen but the

naked valley and boundless prairies in whatever direction the eye is

turned. There is a little more variety after arriving on the North

Platte river . . . [47]

Much less stiff and stilted, and more informative, is

the journal of Pvt. George Gibbs:

Marched sixteen and one-half miles, reaching Fort

Laramie. Finding the grass destroyed by the emigrants in its immediate

vicinity (we) camped a mile or two above on the left (?) bank of

Laramie's river without crossing. We found Major Sanderson's command,

consisting at present of Company E only, already arrived and encamped on

this side of the creek opposite the trading-fort. Major S(anderson),

with (Lieutenant Daniel P.) Woodbury of the engineers, had proceeded

some forty or fifty miles up the Platte to select the site of the new

fort but we were most hospitably welcomed by Captains Duncan and McLane.

The situation of this trading-post is well known from Fremont's report.

report. Hardly anything could be more forlorn or destitute of interest.

The regiment, however, found excellent grass on the river in a pleasant

spot fringed with trees where the facilities for bathing and washing our

clothes were equally welcome. In the afternoon we had an amusing scene

at the lower encampment.

Here follows an account of a drumhead court-martial

staged by the enlisted men for the benefit of an emigrant found in

possession of Army horses. Just as the terror-stricken culprit supposed

he was about to be hanged, an officer intervened and told him to run for

his life, which he did "amidst a volley of balls fired in every other

direction but his, and ran for the hills with the speed of a greyhound."

Gibbs resumes, on the 24th,

. . . Orders had been given out to cut and dry a

quantity of grass in anticipation of scarcity on the route, but Major

Sanderson had returned with information that abundance exists for a

distance of seventy-five miles above here . . . The only change in the

disposition of the command is that Captain Rhett remains here and

Captain (Mc)Lane proceeds with us.

(1st Lieut. Thomas G. Rhett, of South Carolina, would

one day become a hero of the Confederacy.) And on the 25th:

. . . The regiment has crossed the creek and is under

way. This letter goes by special express sent by Major Sanderson under

charge of Captain Perry. A charge of two cents a letter is made to

defray expenses. [48]

|

|

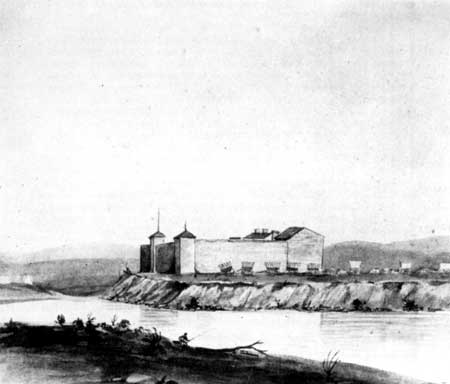

Sketch of adobe-walled Fort Laramie, made on July

11, 1849, by J. Goldsborough Bruff. See text. Contrast the angle of this

view with that of the sketch made by the anonymous Mounted Rifleman,

also herewith reproduced. Courtesy Columbia University

Press.

|

|