|

Fort Matanzas National Monument Florida |

|

NPS photo | |

Matanzas Inlet was the scene of crucial events in Spanish colonial history. The massacre of French soldiers here in 1565 was Spain's opening move in establishing a colony in Florida. The construction of Fort Matanzas in 1740-42 was Spain's last effort to ward off British encroachments on St. Augustine.

Outpost of Empire

Since its founding in 1565, the military outpost town of St. Augustine had been the heart of Spain's coastal defenses in Florida. After Castillo de San Marcos was completed in 1695, the town had only one weakness: Matanzas Inlet, 14 miles south, allowed access to the Matanzas River by which enemy vessels could attack the town from the rear—out of range of the Castillo's cannon. Spain had good reason to fear attack. Beginning with Francis Drake's raid on St. Augustine in 1586, England had repeatedly harassed the Spanish colony. In 1740 Gov. James Oglethorpe blockaded St. Augustine inlet with troops from the British colony of Georgia and began a 39-day siege of the town. A few Spanish vessels managed to break the siege by evading the blockade and resupplying the town. With the onset of hurricane season, Oglethorpe gave up the attack and returned to Georgia.

To prevent the British from controlling the inlet and starving St. Augustine into surrender, carpenters and masons began building Fort Matanzas, with labor supplied by convicts, slaves, and additional troops from Cuba. In 1742, with the fort near completion, Oglethorpe arrived off the inlet with 12 ships. The fort's cannon drove off his scouting boats and the warships left; it had passed its first test. As part of the Treaty of Paris ending the French and Indian War, Florida was transferred to Britain in 1763. After the American Revolution, a second Treaty of Paris returned Florida to Spain in 1784. Spain made little effort to maintain Fort Matanzas, and erosion and rainwater took their toll. When Spain transferred Florida to the United States in 1819, the fort was so badly deteriorated that its soldiers could no longer live inside. The United States took possession in 1821 but never occupied the fort.

The Tower at Matanzas

Fort Matanzas—50 feet on each side with a 30-foot tower—was built of coquina, a local shellstone. Lime for the mortar was made by burning oyster shells. A foundation of close-set pine pilings driven deep into the marshy ground stabilized the fort. Soldiers were rotated from St. Augustine for one-month duty tours at Matanzas, usually a cabo (officer-in-charge), four infantrymen, and two gunners. More could be assigned to this remote outpost when international tensions increased, up to the planned maximum of 50 during a crisis. The soldiers lived and ate together in a sparsely-furnished room off the gun deck; the officer lived in the vaulted room above.

The fort could cover the inlet with five guns: four six-pounders and one 18-pounder. All could reach the inlet, less than a half-mile away in 1742. Loopholes in the south wall of the tower allowed the infantrymen to fire their muskets from inside the fort. Besides warning St. Augustine of enemy vessels and driving them off if necessary, the fort served as a rest stop, coast guard station, and a place where vessels heading for St. Augustine could get advice on navigating the river. But its primary mission was to maintain control of Matanzas Inlet. After thwarting British attempts to gain the inlet in 1742, the fort never again fired its guns in battle.

Exploring Past and Present

1564 Amid the passionate conflicts of the Protestant Reformation, Philip II bf Spain learned that the Frenchman René de Laudonnière had established Fort Caroline in Florida on land claimed by Spain. Fort Caroline provided a perfect base for French attacks on Spanish treasure fleets sailing back to Europe along the Florida coast. Worse, to the devoutly Catholic Philip, the settlers were Huguenots—French Protestants. Despite Philip's protests, Jean Ribault sailed from France in May 1565 with over 600 soldiers and settlers to resupply Fort Caroline. Philip charged Adm. Pedro Menéndez de Aviles with establishing a settlement in Florida and with removing the French. He sailed from Spain with 800 people, arriving at the mouth of the St. Johns River in August, shortly after Ribault. After a brief sea chase the Spanish retired south to the newly founded post they had named St. Augustine.

Jean Ribault sailed on September 10 to attack St. Augustine, but a hurricane carried his ships far to the south, wrecking them on the Florida coast between present-day Daytona Beach and Cape Canaveral. At the same time, Menéndez led a force to attack Fort Caroline. With the French soldiers gone, Menéndez easily captured the settlement. Upon his return to St. Augustine, he learned from Timucuan Indians that a group of white men were on the beach a few miles to the south. He marched with about 50 soldiers to where an inlet blocked nearly 130 of the shipwrecked Frenchmen trying to get back to Fort Caroline.

Menéndez told them how Fort Caroline had been captured and urged the French to surrender; but with no promise of clemency. Exhausted and having lost most of their weapons in the shipwreck, they did surrender. But after they were brought across the inlet, Menéndez ordered them slain. Only 16 were spared—a few professed Catholics and four artisans needed at the new settlement of St. Augustine.

Two weeks later the sequence of events was repeated. More French survivors appeared at the inlet, including Jean Ribault. Again the French surrendered and met the same fate as their fellows. In all, nearly 250 were killed. From that time, the inlet was called Matanzas, the Spanish word for "slaughters." Were these vengeful acts motivated by religion, or, with food already low, was Menéndez simply doing what was necessary for his colony's survival?

Barrier Island Refuge

In preserving the site of historic events on Anastasia Island, Congress also set aside a slice of an intact barrier island ecosystem. Distinct habitats harbor many species, several listed as endangered or threatened. From May to August, the beach is the nesting site for sea turtles, including the loggerhead (threatened) and the green and leatherback (both endangered). The beach is also home to the ghost crab and the threatened least tern.

On the ocean side of the island, sea oats, legumes, and other hardy, salt-tolerant plants growing on the dunes help stabilize them with their extensive root systems. They also provide cover for several animal species, like the endangered Anastasia Island beach mouse.

In the scrub areas, characterized by prickly pear cactus, bayberry, and greenbrier vines, the gopher tortoise digs branching burrows up to 30 feet into the dunes. Other species like the southern leopard frog and the endangered eastern indigo snake exploit the tortoise's labor for their own shelter.

The island's highest part is old dunes covered with coastal forest rooted in thick, decayed remains of pioneer species. Palms, red bay, and live oak provide a canopy sheltering spiders, lizards, raccoons, and the great horned owl and other birds. Berries and fruits on understory plants provide food for some of these animals.

Behind the dunes and forest lie the tidal creeks and marshes of the estuary, where salt water meets fresh. This is the most diverse habitat of the island. Herons and egrets feed on the rich supply of fish and crustaceans living in the salt marshes.

Ospreys and bald eagles fight over the osprey's catch. Pelicans and terns dive head first into the river after the fish. Skimmers fly low over the water. Hawks swoop low over the grass. The tidal flats are alive with fiddler crabs waving their claws. Raccoons, owls, and night herons hunt at night. Marsh rabbits nibble on young sprouts in the morning. There is always action around the salt marsh.

The park is a nesting area for endangered and threatened animal species. Please observe any area closure signs. The ocean beaches, used by marine turtles for nesting and hatching, are closed to vehicles. To help preserve the fragile environment, do not walk or drive on the dunes and do not pick sea oats. Sea oats and other plants help hold the dunes in place. To cut break, or in any way destroy sea oats or other plants may subject you to fines and imprisonment.

Visiting the Park

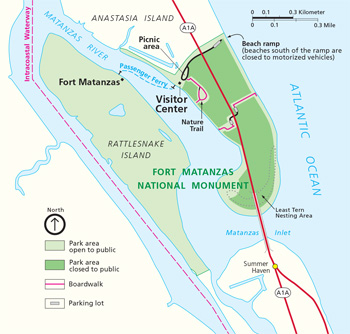

(click for larger map) |

Fort Matanzas National Monument is 14 miles south of Saint Augustine and is reached via Fla. A1A on Anastasia Island. The park is open 9 am to 5:30 pm daily; closed on December 25. There is no admission fee. The park consists of almost 300 acres on Rattlesnake and Anastasia islands.

The visitor center is open from 9 am to 4:30 pm daily. An eight-minute film about the fort and the area's history is shown. Restrooms are at the visitor center parking lot. A passenger ferry carries visitors to the fort, weather permitting, from 9:30 am to 4:30 pm. The ferry and fort are not wheelchair-accessible. The visitor center and restrooms are wheelchair-accessible.

Swimming For pedestrian access to beach, free parking is available in three lots: two beachside and one riverside. Parking lots close daily at 10 pm; no overnight vehicles permitted. Warning: Rip currents are sometimes encountered along the ocean shore. Always swim near a lifeguard.

For Your Safety The river beach near the visitor center contains many sharp oyster shells and slippery rocks along the bank. Do not climb on the rocks or oyster shells; serious injury can result.

Regulations • Alcohol is prohibited. • Metal detectors are prohibited. • No glass containers may be used on the beach. • Visitors must keep pets on a leash and must clean up after them. • The fort may be visited only by ranger-led groups. • Docking private vessels at the fort or letting off passengers is prohibited. • Do not climb or sit on the fort walls. • Visitors are responsible for understanding and complying with all local, state, and federal firearms laws. Federal law prohibits firearms in the park's visitor center, administration offices, restrooms, or fort, and on the ferry boat. These places are posted with signs at public entrances. If you have questions, please contact a park ranger.

Source: NPS Brochure (2012)

Documents

Administrative History of Castillo de San Marcos National Monument and Fort Matanzas National Monument (Jere L. Krakow, July 1986)

Archeological Investigations at Fort Matanzas National Monument (Kathleen A. Deagan, February 1, 1976)

Assessment of Coastal Water Quality at Fort Matanzas National Monument, 2012 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2013/451 (Wendy Wright, M. Brian Gregory and Jennifer Asper, March 2013)

Coastal Hazards & Sea-Level Rise Asset Vulnerability Assessment for Castillo de San Marcos National Monument and Fort Matanzas National Monument: Summary of Results NPS 343/186743, NPS 347/186743 (K.M. Peek, H.L. Thompson, B.R. Tormey and R.S. Young, November 2022)

Cultural Landscape Report: Castillo de San Marcos and Fort Matanzas National Monuments (WLA Studio, February 2020)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Fort Matanzas National Monument (2020)

Final General Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement, Fort Matanzas National Monument (May 2012)

Foundation Document, Fort Matanzas National Monument, Florida (June 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Fort Matanzas National Monument, Florida (January 2016)

Historic Structure Report for Fort Matanzas National Monument, St. John's County, Florida (Luis Rafael Arana, John C. Paige and Edwin C. Bearss, 1980)

Historical Research Management Plan: Castillo de San Marcos and Fort Matanzas National Monuments, Florida (Luis R. Arana, David C. Dutcher, George M. Strock and F. Ross Holland, Jr., December 10, 1967)

Inventory of Coastal Engineering Projects in Fort Matanzas National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRTR-2013/703 (Kate Dallas, Michael Berry and Peter Ruggiero, March 2013)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Fort Matanzas National Monument (2016; for reference purposes only)

Landbird Community Monitoring at Fort Matanzas National Monument, 2010 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2011/297 (Michael W. Byrne, Joe C. DeVivo and Brent A. Blankley, September 2011)

Long Range Interpretive Plan, Fort Matanzas National Monument (July 2002)

Map: Road Approach Topography (June 19, 1934)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Fort Matanzas (Luis R. Arana, July 14, 1973 revised June 1976)

Fort Matanzas NM Headquarters and Visitor Center (Cynthia Walton, June 17, 2008)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Castillo de San Marcos and Fort Matanzas National Monuments, Florida NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRR-2012/515 (Jessica L. Dorr, David M. Palmer and Rebecca M. Schneider, April 2012)

Resumen del documento fundacional, Monumento nacional Fuerte de Matanzas (January 2016)

Shoreline Change at Fort Matanzas National Monument: 2019–2020 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2021/1327 (Lisa Cowart Baron, May 2021)

Shoreline Change at Fort Matanzas National Monument: 2020–2021 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2022/1343 (Elizabeth Claire Schmidt, January 2022)

Summary of Amphibian Community Monitoring at Fort Matanzas National Monument, 2009 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN//NRDS-2010/096 (Michael W. Byrne, Laura M. Elston, Briana D. Smrekar, Marylou N. Moore and Piper A. Bazemore, October 2010)

Terrestrial Vegetation Monitoring at Fort Matanzas National Monument: 2019 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2022/1352 (M. Forbes Boyle and Elizabeth Rico, May 2022)

Terrestrial Vegetation Monitoring in Southeast Coast Network Parks: Protocol Implementation Plan NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR-2019/1930 (M. Forbes Boyle, M. Brian Gregory, Michael W. Bryne, Paula Capace and Sarah Corbett, May 2019)

Theme IV: Spanish Exploration and Settlement. National Historic Landmark Theme Studies (April 1959)

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Fort Matanzas National Monument, 2009 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2012/255 (Michael W. Byrne, Sarah L. Corbett and Joseph C. DeVivo, March 2012)

Volunteer Handbook: Castillo de San Marcos & Fort Matanzas National Monuments (July 2021)

foma/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025