|

FORT NECESSITY

New Light on Washington's Fort Necessity A Report on the Archeological Explorations at Fort Necessity National Battlefield Site |

|

PART II.

ARCHEOLOGICAL EXPLORATIONS

PREVIOUS ARCHEOLOGICAL EXPLORATIONS

The 1901 Project

The first careful examination of the site after Freeman Lewis' visit in 1816 took place in 1901 when Archer Hulbert went to Great Meadows to secure firsthand information for his account of the Braddock Road in the "Historic Highways of America" series. He was familiar with the controversy over the shape of the remains, and states that he went there convinced that Lewis, rather than Sparks was correct. [1] The owner of the land, however, pointed out that the visible surface remains did not conform to the Lewis survey. Robert McCracken, a surveyor, was in the Hulbert party and he soon discovered that two sides of the Lewis triangle were correctly mapped, but that the base of Lewis' triangle was not represented by visible traces. [2] They also found a third ridge, as distinct as the two correctly mapped by Lewis, but not shown on his map. In addition to these more conspicuous ridges and depressions, Mr. Fazenbaker, the owner, also called attention to a very faint trace of an isolated ridge along the fourth side near the Run, marked "O" on McCracken's map (Fig. 6).

Hulbert did enough digging to convince him that the main ridges were man-made, but what seemed more important to him was finding in "Mound O" what he believed to be remains of the original stockade. [3] Here, in two cross trenches (location unknown) at a depth of "about four and one-half feet", a considerable amount of bark was encountered. He interpreted this bark to be remains of the original stockade posts, and made quite a point of the alleged fact that bark is more durable than wood. This bark, which turned out to have no connection with Fort Necessity (see page 60), was encountered also in the 1931 excavations, and again interpreted as remains of Washington's "palisado'd Fort". It was simply a case of wishful thinking, but it seemed to Hulbert, as it did to later excavators, that this discovery furnished final proof that Lewis' triangular plan was in error. [4] It would almost seem that Hulbert was more interested in disposing of Lewis and Veech than in finding the remains of Fort Necessity, although I may be doing him an injustice. But in spite of his concern with Lewis' mistake, his major contribution was in noting and recording "Mound O", since the slight trace of this ridge had completely disappeared by 1931. As pointed out later in this report, the presence of a ridge at this location was a major factor in arriving at an entirely new interpretation of all the ridges, thus leading to the discovery of the original fort remains.

Hulbert refers to certain "relics" as having been found at the site, including "the barrel of an old flint-lock musket, a few grape shot, a bullet mould and ladle, leaden and iron musket balls". [5] The present location of these objects is not known.

The 1931 Project

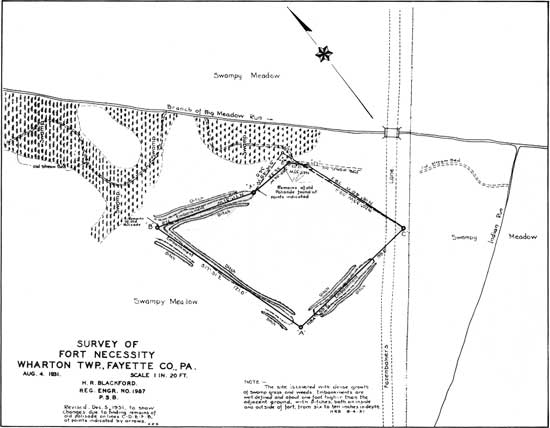

Only a brief summary of the 1931 excavations will be given here, since the excavator's account is appended to this report. The explorations carried out in preparation for the Washington Bicentennial Celebration developments were supervised by Harry Blackford, a Civil Engineer, who had mapped the site for the Memorial Committee in August of the same year (Fig. 9). [6]

|

| Fig. 9. Survey made by Harry R. Blackford, 1931. |

The first step in the archeological excavating, which began on November 17, was to dig "exploratory trenches at right angles to the existing embankments to determine, if possible, the location of the old stockade with reference to the embankments". [7] Finding no evidence of stockade remains in these cross trenches, the next step was to put down a continuous trench, approximately 3 feet wide and 2 to 3 feet deep along the crest of each of the three ridges. Where remains of embankments were no longer visible, these lineal exploratory trenches followed the general location of the fort outline shown on McCracken's map. Finally, at one point in this trench, at the northernmost section, near the Run, several post ends were found in what appeared to be a straight line. Using the new evidence, which departed at this point from the McCracken (Hulbert) map, the trench was continued in a straight line toward the point where the surface traces played out. Only one additional post fragment was found along these assumed lines of the fort, but the same bark reported by Hulbert was encountered, and again erroneously interpreted as remains of the stockade posts.

No plan was made showing the location of the 1931 explorations, but the lineal trenches were marked imperishably when they were filled with concrete as an anchor for the new posts of the reconstruction. Nor was a map made showing the exact position of the few post ends encountered, but, from the narrative account, it would appear that a short, continuous section was uncovered, as well as at least one isolated post (Fig. 21).

Although the first exploratory cross trenches would have intersected the original ditches of the entrenchments, these remains were not recognized. Nor was the line of the original circular stockade noted when it was crossed, except at those points where post remains occurred, and even there it was observed as a straight line rather than curved. The stockade line was later intetsected at several points in digging the trenches for the drain tiles, and several post ends were encountered, but they were not recognized as being significant since they were not found along the traditional or assumed line of the stockade. (Fragments of post ends were found during the 1953 excavating that had been thrown back into the drain tile ditches near where they crossed the original stockade.) A section of the stockade remains was also encountered when digging the hole for the flag pole, but, again, the wood fragments had no business being there, and so were dismissed as of no possible importance, if, in fact, they were noticed. Failure to note evidence of the original entrenchments or the stockade trench where post ends were missing is not at all surprising, since the people who did the excavating were not experienced in distinguishing subtle soil differences. Moreover, they were looking strictly for stockade evidence in the form of wood remains, and such remains, according to the accepted theory, lay in straight lines, mostly represented by visible surface ridges.

Quite a few "relics" were found during the 1931 excavating, as well as during the site development the following spring. They include lead and iron balls, a concentration of swan shot in one of the drain tile trenches, a few fragments of glass and china, and bits of rusty iron. This material is described, along with that found in the 1952-1953 explorations, in a later section.

THE SETTING

Although I promised in the Preface not to give a detailed description of the geography of the site and its flora and fauna, some mention of the physical setting is needed. Winding irregularly between low bordering hills for a distance of 1-1/2 to 2 miles is a typical upland meadow, called "Great Meadows" even before Washington's first visit. Some 200 to 300 yards wide, it is traversed by a small meandering stream known as Meadow Run. [8] Except for certain areas which have been altered in recent years, the meadow is marshy, with typical marsh vegetation — grasses generally, with alders and small bushes along the stream banks. [9] During spring floods, and possibly at times of heavy rains, the stream has overflowed its banks and over the years has gradually built up the floor of the plain. Archeological evidence shows that the meadow was 2 to 3 feet lower in relatively recent geological times, with indications of a heavier growth of vegetation, but the geological history of the area is really of no concern to us here.

The present meadow is relatively level, with an elevation of around 1840 feet above sea level. The ground slopes up from the edges of the flat bottom land, rather gradually at first, then more sharply to irregular ridges and hills, which reach an elevation of 1900 to 2100 feet. In 1754 a hardwood forest apparently began at the edge of the meadow (Fig. 1). These woods furnished logs for the stockade, and also provided shelter for the attacking French soldiers. Contemporary accounts of the battle indicate that the woods came to within 60 yards of the fort on the southeast side, but were beyond musket range on the other sides. The old trails and roads skirted the meadow, running just inside the woods line, presumably to stay on drier ground (Fig. 1). The area selected by Washington for his camp, and later for the fort, apparently was a slightly elevated knoll or tongue of higher ground extending into the meadow. [10] It was bounded on one side by a small tributary of Meadow Run, known as Indian Run. The presence of this second stream, which, with the meandering bed of the main stream, provided natural defenses for the troops until they could build their own, probably was the primary reason for selecting this particular site for the camp.

Today the scene has changed in many respects, although as noted previously, the terrain within the Battlefield has been restored to its earlier wooded condition. It has been reforested with pine, however, rather than oak. Outside the Battlefield most of the sloping land adjoining the meadow is under cultivation. Also, the meadow itself in the immediate vicinity of the fort site has been altered considerably. First of all, about 100 years ago a straight channel was dug for the portion of the Run adjacent to the fort. In 1932 the grading operations in the 2-acre memorial tract raised the ground level as much as 2 feet or more in places. Other work carried out at that time and during the later development of the Battlefield, such as the entrance road and parking area, has changed considerably the appearance of the meadow. Even more recently an earth dam has been built just upstream from the fort site, forming a small reservoir. Actually, none of these alterations had any real effect on the archeological explorations, other than the additional digging necessitated by the 1932 fill.

Nature, however, was more successful in confusing the archeologist through the activities of crayfish. Even though the site allegedly had never been cultivated, the ground had been worked over quite thoroughly by these industrious creatures, making it very difficult to distinguish soil differences at the upper levels. Moreover, these innumerable crayfish holes, some bigger than a shovel handle, were responsible for finding lead musket balls and other objects at a much lower level than they should have been.

OBJECTIVES

The program of archeological exploration at Fort Necessity can be divided into two distinct phases having quite different objectives. The first corresponds with the opening season's field work (August-September, 1952), and the second with the two periods of field work in 1953 (April and September).

Before excavating began in 1952, an "orientation" report was prepared, in which pertinent documentary materials were synthesized and interpreted as a guide to the archeologist in planning and reporting on the excavations. [11] The conclusions as to the physical appearance of Fort Necessity presented in this pre-excavation report followed those generally accepted over the years. The report, on the whole, dealt with the controversy as to whether the original stockade had been triangular in plan, or more square-shaped, a discussion that had been going on for over a hundred years. Even after assembling and reviewing all the documentary evidence, none of us seriously considered the third alternative of a small, round stockade — actually the only one of the three alternatives supported by contemporary documentary evidence. It was still assumed that both Shaw and Burd had actually observed an irregular, but straight-sided stockade, which appeared superficially to them to be round.

In the preliminary explorations, the primary concern was to locate the entrenchments presumably lying outside the stockade erected in 1932. It was thought that the restoration of this feature would be an interesting and valuable supplement to the reconstructed stockade, and would fill out the setting so that the story of the battle would be more intelligible to visitors. Secondary objectives were 1) to settle, once and for all, the "triangle versus square" controversy, 2) to establish the 1754 location of the stream bed, and 3) to secure additional objects for museum display. It was taken for granted that the excavating and construction carried on in 1931 and 1932 would have destroyed all remains of the original stockade, Recovery of additional information on this feature, therefore, seemed quite unlikely.

The second phase of the archeological explorations was concerned with locating the circular stockade and securing as full information as possible on the entire fort. Such a project, however, was quite unforeseen when the first season's field work was started.

EXCAVATING PROCEDURE

Three factors limited the extent of the preliminary explorations, and, to some extent, the later more extensive excavations. These were 1) the fill made in connection with the 1932 developments, 2) existing features, such as walks and lawn, and 3) limited funds. In the area explored, fills up to over a foot in depth had been made in 1932 for the purpose of providing a less marshy condition around the reconstructed fort, and to lessen the danger of inundation during spring floods. Ideally, this earth fill might better have been removed entirely, with power equipment, before starting the archeological work, but, for obvious reasons, such a plan was not practicable. Even though additional digging caused by this foot or so of fill limited the extent of testing that could be accomplished with the funds available, it is doubtful whether any more exploring would have been done in any event, for the only foreseeable result at that time was the recovery of more relics. Since it was assumed that the surface of the ground had been examined thoroughly before the fill was made, it seemed unlikely that any sizable objects would be found. Although it eventually became necessary to remove the 1932 stockade, as well as the paved walks, nothing so drastic was anticipated when the field work started.

When the excavating began in 1952, it was expected that only a few exploratory trenches would be dug. It did not seem necessary, therefore, to lay out the site on a grid system, particularly since the trenches could not be oriented with the grid lines in any event. The trenches, therefore, were designated "A", "B", etc., and were tied into the permanent boundary markers at the corners of the 2-acre tract. The same system was continued at the outset of the second season, for even at that time it was not yet known whether the modern structures would have to be removed. As soon as archeological evidence made it quite clear that the 1932 reconstruction was incorrect and would have to be replaced, the area was staked out on a regular coordinate system and subsequent trenches laid out in reference to this grid. For convenience, the 252-foot "south" side of the 2-acre rectangular tract was assumed to run east and west, with the southwest property marker designated as the zero point on the grid.

The top of the northeast corner marker, recorded in Blackford's field notes as elevation 1845.62 feet above sea level, was used as the datum for all vertical measurements. In some instances, features, soil levels, and artifacts were recorded by surface depth, without reference to the datum. Such figures, however, can be transposed to actual elevation, or vice versa, since surface elevations were recorded at each stake and at intermediate points as indicated by irregularities in the topography.

Exploratory trenches were either 3 or 5 feet wide, depending upon the nature of the anticipated feature. When an important feature was encountered, the trench was widened, as required.

Field records for the project consist of detailed notes in engineers' bound field notebooks; field drawings on 18 x 23 inch cross-section paper; and photographs, both black and white and colored. All objects were numbered in a continuous series (1 through 243). Wood fragments, consisting mostly of water-preserved post ends, were treated in different ways to assure preservation of typical examples. On most of the larger pieces, no preservative was used, the wood being allowed to dry out very slowly. After two years, the wood appeared to be quite sound, and further proof that this is a satisfactory method is offered by the untreated pieces excavated in 1931, which are in excellent condition. A few sample specimens of wood were dried out by the alum-glycerine treatment and then impregnated with a solution of linseed oil, turpentine, and acetone. Iron objects were preserved by the standard treatment of mechanical and chemical rust removal, with final paraffin coating. All objects, including those recovered in 1931 and 1932, are on display at the Fort or in the Tavern, or are in storage at the Tavern.

1952 PRELIMINARY EXPLORATIONS

Plan of Attack

Archeological explorations were started in August, 1952, for the express purpose of locating the entrenchments which presumably would be found just outside the stockade. At this time there was no inclination on anyone's part to question the correctness of the 1932 reconstruction, particularly as to the location of the stockade. There is no contemporary description of these entrenchments, and none of the later visitors to the site, with the exception of Jared Sparks, makes any mention of them. [12] Colonel James Burd, however, almost certainly was referring to the entrenchments when he noted after his visit in 1759 that "there is a small ditch goes around it (the stockade) about 8 yards from the stockade." [13] Whereas Burd left no drawing, Sparks provides us with a map purporting to be an accurate record of what he claimed to have observed at Great Meadows when he visited the area in 1830 (Fig. 3).

Several things in Sparks' drawing, however, raised doubts as to its reliability. Although the plan of the stockade appeared to conform, in general, to the plan established by Hulbert and by the 1931 explorations certain details, such as the three entrances, did not quite ring true. There were other reasons for questioning Sparks' map, notwithstanding its superficial appearance of authenticity. Although it showed many features in considerable detail, the few that can be checked — such as the "Road from Wills Creek" and the two streams — were seen to be inaccurately drawn. We could not overlook completely, however, the entrenchments, which Sparks showed approximately 20 feet from the line of the stockade, particularly when this conforms so closely to Burd's "8 yards". On the other hand, it was recalled that Lewis and Veech, who made a detailed survey of the site several years before Sparks' visit, had not been able to find any trace of entrenchments, although they searched the ground for them. However, we had no clear-cut evidence that Sparks had not seen and correctly recorded the entrenchments, and there was no good reason for not using his convincingly delineated map as a starting point for laying out the first test trenches. It was assumed that evidence of the entrenchments would be found within a reasonable distance of the stockade, and it seemed most likely that they would have been located on the south and west sides of the stockade, as shown by Sparks.

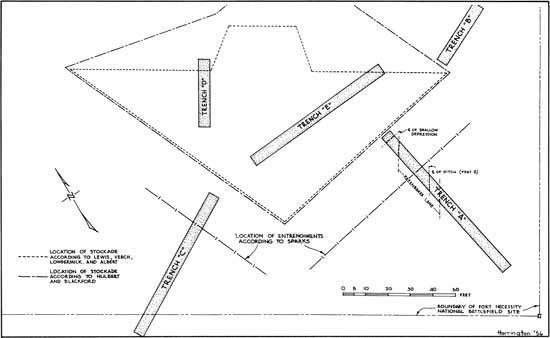

Two exploratory trenches were dug on the outside of the reconstructed stockade specifically in search of these entrenchments (Trenches "A" and "C", Fig. 10). A third trench, "B", was dug at the southeast corner for the purpose of checking original topography and soil conditions in the vicinity of the Run. We even considered the possibility of finding evidence of conventional pointed bastions at the corners, so convinced were we at that time that the original stockade corresponded in general with the 1932 reconstruction.

|

| Fig. 10. 1952 exploratory trenches in relations to various theories as to location of original stockade and entrenchments. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The nature of the earth made it rather difficult to detect old soil disturbances, largely because of its wet, marshy character, and because of the great number of crayfish holes that extended from the surface to a depth of two to three feet. The farm road (Fazenbaker lane) also confused things in Trench "A". Although its location was known (mapped by Blackford in 1931), it was assumed that the lane was relatively superficial and would not extend deep enough to obliterate remains of the original entrenchment.

Not finding evidence of a ditch at a likely distance from the stockade, the first two exploratory trenches were extended as far as there seemed any possibility of the entrenchments having been located (80 feet for "A" and 70 for "C"). Although some interesting information came to light, no evidence of the ditch of the 1754 entrenchments was found in either trench. It was recognized that the shallow remains of the old ditch could have been obliterated by the lane, or made indistinguishable through years of crayfish activities. It was also realized by this time that the exploratory trenches had not been too well located, at least not for the purpose of checking Sparks' plan. Excavation of other test trenches outside the stockade was considered, but it was decided that this would have to wait until it was possible to carry out a more extensive program of explorations. Funds for the first season's tests were quite limited, and there was still the matter of looking for the base of the Lewis-Veech triangle.

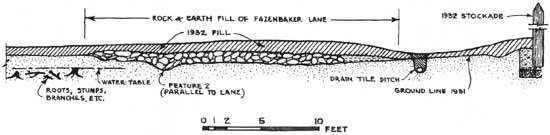

Trench "A"

The principal results from the excavation of this 80-foot trench were 1) negative evidence on the entrenchments (although not too satisfactory because of the deep disturbance of the lane), 2) exact location and certain construction details of the lane, 3) information concerning the natural soil conditions and the grading accomplished in 1932, and 4) location and depth of the shallow ditch along the outside of the ridge (confirming Blackford' 1931 survey).

The remains of Fazenbaker's lane, although found in the location shown on Blackford's map, were much more extensive than anticipated. But even though the ground had been disturbed to a depth of over a foot below the 1754 grade, some evidence of the entrenchment ditch should have been found if it had been in this location. In the vicinity of the fort, where the ground was low and marshy, earth and stones had been added to the roadbed of the lane from time to time. Where Trench "A" cuts the lane, this fill was more than a foot thick, and spread over a width of some 20 feet (Figures 10 and 11). Before the stone fill was made, there had been a ditch along the southeast side of the lane (Feat. 2, Fig. 11).

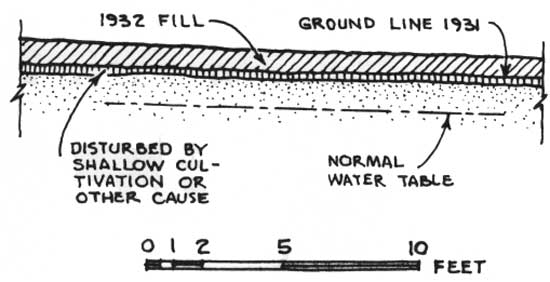

|

| Fig. 11. Simplified Profile — Trench "A" |

A full description and analysis of the various soil layers adjacent to the lane would require specialized geological study. Moreover, it is irrelevant to the present discussion, since all but the layer added in 1932 are natural deposits, and presumably date from well before 1754. Of interest to the present study, however, is the deep clay layer in which were found remains of tree roots, branches and grass. These remains of an ancient marsh vegetation were preserved by having been below the normal water table, and thus continuously wet. This buried plant zone obviously has no connection with the history of Fort Necessity, but its discovery in the exploratory trenches quite definitely contributed to the discovery of the original stockade, as later discussions will show. The soil above this zone appears to be a combination of natural humus development and flood deposits.

In the short distance between the lane and the existing stockade, the situation was confused and it was not possible to determine the 1754 ground line with any certainty. The trench profile did confirm the recent known history of the site beginning with the excavations of 1931. A trench had been dug along the crest of the still visible ridge, about 3 feet wide and 2.5 to 3.0 feet deep. (See description of 1931 excavations, Appendix 6.) When the stockade was reconstructed the following spring, a six-inch layer of crushed rock was laid in the bottom of this trench, on which was poured a thin layer of concrete. The stockade posts were then set on the concrete-stone footing and the entire space around the posts filled with concrete. Extensive grading followed, in which a wide, shallow depression was formed along the outside of the reconstructed stockade, and a firing step formed on the inside (Fig. 25). A tile drain, placed under the outside depression, further confused the soil picture. But in spite of these disturbances, it was possible to determine the pre-1931 surface, except along the crest of the ridge. A slight depression was noted in the Trench "A" profile, 3.5 feet from the centerline of the earlier excavation trench. This checks with Blackford's survey and undoubtedly represents the depression mapped by Lewis in 1816 and still faintly visible in 1931.

Trench "B"

This 30-foot trench was dug primarily to observe soil conditions in the vicinity of the original creek bed, and to see if the natural soil profile, as already noted in Trenches "A" and "C", also obtained in this area. No evidence of the "lost" entrenchments or extension of the stockade was found here. The most important observation was the presence of the deep clay layer containing remains of vegetation, exactly as found in Trench "A", although it was slightly deeper than in the first trench; not surprising in view of the proximity of the stream bed (Fig. 12). The 1754 ground line was readily apparent, with the thin edge of the Fazenbaker lane deposits lying directly on it. Above this was the 1932 fill, here a little more than a foot thick. The trench was not extended far enough to reach the original stream bed, but the soil conditions and the slope of the old ground line indicated that it must have been just beyond the end of the trench, which confirms the location recorded by Blackford in 1931 from surface traces.

|

| Fig. 12. Simplified Profile — Trench "B" |

Trench "C"

This trench, dug expressly in search of the original entrenchments, produced nothing of importance. It showed the normal soil conditions better than Trench "A", since the only post-1754 disturbances revealed in its 70-foot length were a superficial road fill (part of the 1932 developments) and the grading done in connection with the reconstruction.

Trenches "D" and "E"

The purpose of these two trenches was to check on the possibility of there having been some feature here to account for the base of Lewis' triangle (Figures 14 and 15). The surface of the ground had been examined here by Blackford when he mapped the site in 1931, and he had found no surface traces of any sort. In 1901, Hulbert and McCracken also had looked for evidences. However, no one had checked below the surface, and it was felt that the century-old argument could possibly be settled even more convincingly by some archeological testing. The two exploratory trenches were so located that they would cross the line in question.

|

| Fig. 13. Simplified Profile — Trench "E" |

|

| Fig. 14. Exploratory Trench "D" inside 1932 stockade. |

|

| Fig. 15. Exploratory Trench "E" inside 1932 stockade. |

Absolutely no subsurface disturbance, other than the drain tile ditches dug in 1932, was found in either trench. What was believed to be the 1754 ground line was quite evident in both trenches, although later evidence raised some question as to the accuracy of this interpretation. The situation was this. A humus layer, averaging about 3 inches in thickness, was found along each profile, lying directly below the 1932 fill (Fig. 13). Below this thin upper humus layer was a more normal natural humus zone. The line of demarkation between the two was quite indistinct, but nevertheless was there. At first this upper portion of the humus zone was thought to have been caused from intensive use of the site in 1754 — men and animals tramping over the ground when it was wet. This, however, would probably not have disturbed the ground to so uniform a depth. The only other conclusion is that the site had been subjected to relatively shallow cultivation. Further evidence for the latter interpretation came from subsequent excavating, and one is forced to the conclusion that Mr. Fazenbaker's claim that the site had never been under cultivation was in error (see page 44 and 46).

The few artifacts found in the excavating came from this upper disturbed zone (except those that had fallen into crayfish holes). They consisted mostly of lead musket balls, gun flints, and small iron cannon balls, and will be described along with the objects from the 1953 excavating.

Summary

Although the location for the three exploratory trenches outside the stockade had not been selected ideally, the evidence from them indicated that there had been no entrenchments in the area explored. Nor had the explorations thrown any new light on the function of the ridges and depressions along which the 1932 reconstruction had been erected. The discovery of roots, branches, and bark in Trenches "A" and "B" at approximately the same depth as the bark reported from the 1931 excavating was very revealing. Blackford had found "pieces of charred wood and lumps of charcoal" at a depth of "about three feet" (Appendix 6), and interpreted them as remains of the original stockade. Finding these remains of vegetation in 1931 was one of the principal arguments advanced at that time for the stockade plan as reconstructed the following year. It now appeared probable that the bark and "charcoal" encountered by Blackford was the ancient buried vegetation and had been misinterpreted as remains of the original stockade posts.

Discovery of the nature and extent of the Fazenbaker lane also proved valuable in working out a new theory for the location of the original stockade. A section of ridge had been noted by Hulbert early in the nineteenth century, and was shown on the sketch map prepared for Hulbert by Robert McCracken ("Mound O", Fig. 6). Blackford was unable to find any trace of this ridge when he mapped the site in 1931. Noting that the ridge and depressions mapped by Blackford between points "A" and "C" (Fig. 9) stopped at the edge of the lane, it was considered likely that the ridge noted by Hulbert might also have stopped at the lane. Plotting this ridge accordingly on the base map suggested that it, too, stopped at the edge of the lane. It was quite obvious now that the ridges near point "C" had not been obliterated by flood action, as all writers had contended previously, but by construction of the lane. Blackford undoubtedly was correct when he assumed that the ridges originally had continued to "C".

The preliminary explorations left certain questions unanswered, and raised others. Why had we not found those well-documented entrenchments? Was it because we had not dug in the right places, or was it because the evidence had been obliterated or confused by later disturbances, such as the Fazenbaker lane? Should the search be continued in other directions from the fort, and possibly at a greater distance? It was also possible, although we were reluctant to press the point, that remains of the entrenchments were present but had not been recognized. Each of these problems were considered, for we knew that the entrenchments had been some place in this vicinity, and almost certainly not very far from the line of the stockade.

A New Stockade Theory

It has already become legend that the discovery of a previously unknown document (the Shaw Deposition) was responsible for the new theory that the stockade had been circular, rather than squarish or triangular in plan. The truth is that this document was looked upon with favor only after the theory of a circular stockade was advanced in the archeological report for the 1952 preliminary explorations, and was, in fact, not exploited in publicity until after the circular stockade was found. The document had been known, however, long before the new theory was worked out, and had, in fact, been dismissed by everyone concerned, as unreliable evidence. When the exploratory excavations were started in 1952, there still seemed to be too much evidence in favor of a straight-sided stockade, and everyone was content with the existing reconstruction, or, at least, with its location.

The three main factors that brought a reappraisal of the evidence, resulting in a new theory as to the location and shape of the stockade and location of the entrenchments were 1) the absence of remains of the entrenchments in the exploratory trenches, 2) the absence of ridges and depressions in one area only (their absence at the lane had now been accounted for, and erosion by the creek, when it overflowed its banks, could no longer be credited with the total obliteration of the traces in the single vacant space), and 3) the fact that stockades were not usually constructed by piling up earth against the posts. A minor factor that also had to be considered was the bulge shown at the north side of the fort on all early maps of the site, particularly those prepared by Lewis and Sparks, both of whom had visited the area before it had been disturbed. Later writers rationalized this bulge as representing an extension of the stockade over the creek for access to drinking water, but the early visitors to Fort Necessity must have observed some evidence on the ground to have caused them to map this extension. The interesting point was that this bulge lay exactly in the space where the ridges and depressions, always assumed to be remnants of the stockade, were missing.

In regard to the method of constructing the stockade, even if earth had been piled against the posts to strength them, there would have been no need to have set them 3 feet in the ground, the depth at which the few posts ends were found in 1931. The 1952 explorations showed that at this depth the bottom ends of the posts would have been preserved by ground water. Why, then, had no post ends been found along the ridges, and corollarially, why were the ones that were found all from the section where there was no ridge? These are some of the questions that arose when the results of the preliminary explorations were appraised in the light of all other evidence; questions that could not be answered satisfactorily by the currently accepted theory that the stockade had originally been located along the ridges.

Once these questions had been raised, and other inconsistencies considered, it was quite natural that the discarded documentary evidence for a small, circular stockade should be looked at again with a less prejudiced view. After weighing all the evidence very carefully, and, at first, rather hesitantly, a report was submitted suggesting that the ridges and depressions were not the remains of the earth banked against a stockade, but rather the remains of the entrenchments, Working on this thesis, it was a natural step to the theory that the stockade had, in fact, been small and circular, and had been located in the space where the ridges were lacking. In the report presenting this new idea, which also outlined plans for future explorations, a circular stockade, roughly 54 feet in diameter, was proposed. [14]

1953 EXPLORATIONS

Summary of Procedure and Results

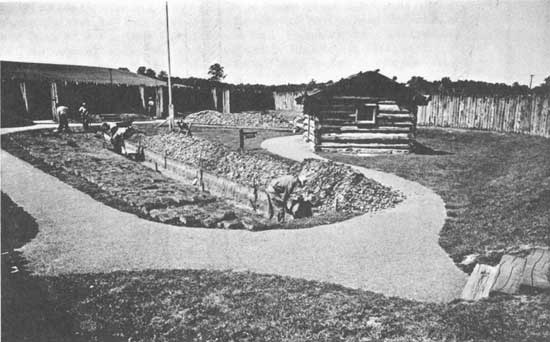

Excavating was resumed in the spring of 1953 with quite definite objectives based upon conclusions and recommendations presented in the report on the previous year's preliminary explorations. [15] These objectives were 1) to check the circular stockade theory, and, if found to be correct, to obtain as much information as possible on the stockade's original construction; and 2) to look for evidence of the outer entrenchments, which, according to the newly developed theory, would be found under the reconstructed "firing step" just inside the 1932 stockade.

We started by laying out three test trenches across the calculated line of the circular stockade (Trenches "G", "H" and "I", Fig. 16). The presence of paved walks, the log cabin, and the high "firing step" along the reconstructed stockade limited the area that could be explored and still keep the site open to the public. Before the removal of these features could be justified, it was necessary to demonstrate clearly the validity of the circular stockade thesis.

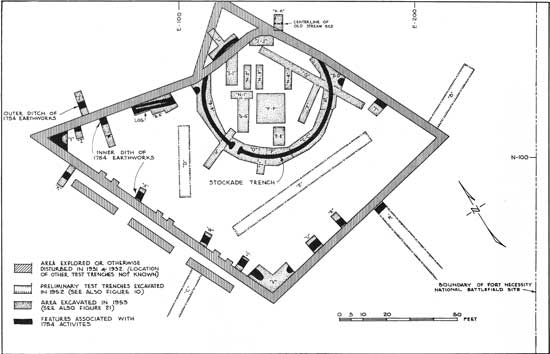

|

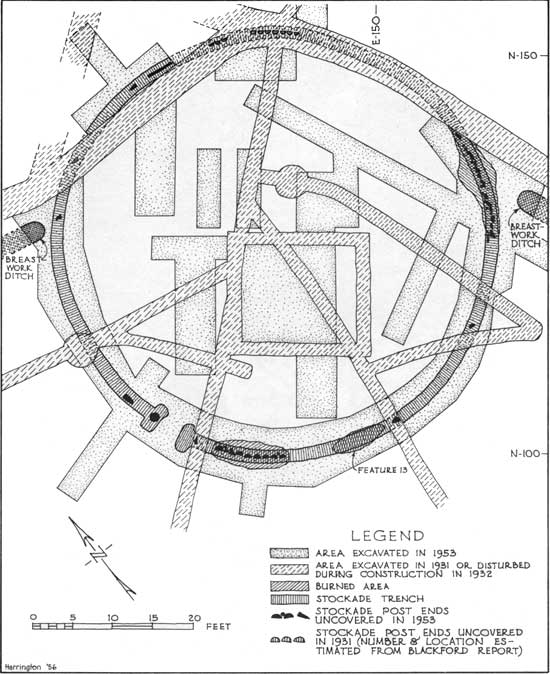

| Fig. 16. Location of excavations of 1931, 1952, and 1953 showing archeological features associated with Fort Necessity. (click on image for a PDF version) |

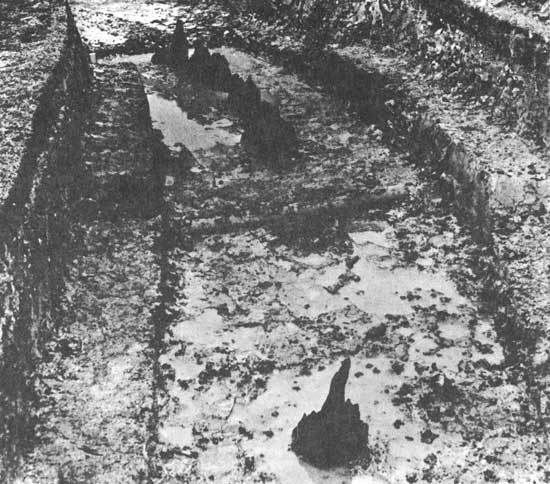

After removing the 1932 fill and a post-1754 accumulation or disturbance from shallow cultivation, an intrusive band of earth was noted in each of the three test trenches. This band of differently colored earth varied in width in each of the three trenches, but was roughly a foot and a half wide. It was quite evident that these bands represented an old ditch or trench, and their position conformed almost exactly to the pre-exploration calculation of the circular stockade location. There could be little doubt about this being the line of the original stockade but even more conclusive evidence was soon to be found as we went deeper. Charcoal and burned earth was found in two of the three trenches (Fig. 17), and, at the level of normal ground water, remains of wood posts were encountered in the same two trenches in which charcoal and burned earth had been noted at a higher point (Figures 18, 19, and 20). These water-preserved post ends averaged from one to one and a half feet in length, and were found standing in a vertical position. The lower ends rested on the bottom of the original stockade trench, which had been dug to a depth of 2.0 to 2.3 feet below the 1754 ground line. There was no doubt now that the original stockade had been found, and almost exactly according to the estimated location.

|

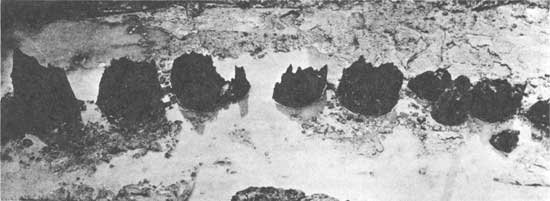

| Fig. 17. Charred remains of stockade posts lying just below 1931 ground line (Trench "O-I-P"). |

|

| Fig. 18. Second section of water-preserved post ends (Trench "D-D"). |

|

| Fig. 19. First section of water-preserved post ends (Trench "O-I-P"), with round gate post in foreground. |

|

| Fig. 20. Close-up of portion of first section of water-preserved post ends. |

The stockade was then checked at a fourth point on the circle, permitting its outline to be plotted with considerable accuracy. It was found to be almost exactly circular, with a diameter of roughly 53 feet. Very little more digging was done in the vicinity of the stockade during the spring of 1953, since it was now evident that the walks, as well as the entire 1932 stockade and log cabin, would have to be removed before the area could be excavated systematically. Quite obviously we would now have to give up entirely any idea of revising the earlier reconstruction; it would have to be removed and rebuilt completely.

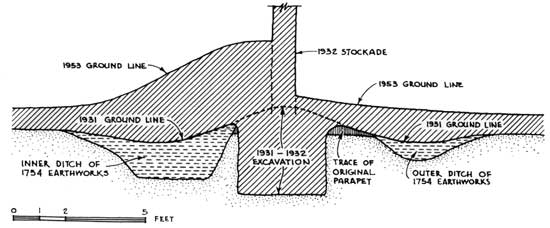

The principal thing left to be done at this time was to check under the reconstructed "firing step" for evidence of the original outer entrenchments, which we were now more confident than ever would be found just inside the line of the reconstructed stockade. Excavating soon showed the validity of this thesis. Not only was the inner ditch of the original entrenchments found in each of the three test trenches (Trenches "M", "R", and "S"), but their exact size and shape could be determined. Fortunately, the 1931-1932 excavating had followed along the center of the ridges (the remains of the original parapet), leaving the ditches unmolested. Work was terminated at this point, postponing fuller excavation and the demolition of modern features until after the summer travel season.

Excavating was resumed in September, the first operation being the removal of the 1932 stockade, "firing step", log cabin, and paved walks. It was then possible to follow out the entire length of the circular stockade, or that portion which had not been destroyed by the 1932 developments. Because of the fill placed over the entire area in 1932, averaging nearly a foot in depth, it was not feasible to excavate as much of the site as desired. For example, instead of following out the entire length of the entrenchment ditch, it was checked only at intervals by a series of cross trenches (Fig. 16). About half the area inside the original stockade was explored, although we soon discovered that the ground here had been disturbed considerably in 1932 in laying a network of underground drains and in constructing the log cabin. No excavating was done beyond the limits of the line of the original entrenchments, except to locate the earlier course of the stream where it had come closest to the circular stockade.

In the following detailed discussions of the principal archeological features, identification and interpretation will be presented along with the discussion of evidence found in the excavating. Description and interpretation of objects found in the excavations will be discussed under functional groups (cannon, small arms, uniforms, other military equipment, etc.).

The Circular Stockade

Approximately one-fourth of the stockade had been destroyed in the course of the 1932 work, but there was enough left to determine quite accurately its original plan and method of construction. Equally interesting was the clear evidence of how the stockade had been destroyed by the French the day after the battle. It had been almost exactly circular in plan, varying in overall diameter from 53.0 to 53.5 feet (Fig. 21). The stockade trench varied in cross-section from point to point, but its general character was the same throughout, as shown in Fig. 22. In digging this trench, the men had worked from the inside of the circle, since the vertical face of the trench was always on the outside and the sloping face on the inside. The trench varied from 2.2 to 2.5 feet in width at a point just below the thin pre-1932 plowed or disturbed zone. Although post remains were missing completely along much of the stockade trench, there was no difficulty in locating it, as the trench fill contrasted quite definitely with the natural yellow clay subsoil into which the trench had been dug.

|

| Fig. 21. Detailed plan of exploration in vicinity of circular stockade, showing 1931-1932 and 1952-53 excavations and principal archeological features. |

|

|

Fig. 22. Cross-section and plan of stockade trench. a. Typical cross-section at point where posts were burned in place. b. Plans of two sections of stockade where posts were burned in place. A third similar section was probably encountered in 1931. |

Careful examination revealed no irregularities at the 1931 ground line which would mark in any way the presence of the stockade trench, If there ever had been anything of this sort, such as earth thrown out when the trench was dug originally, or a depression from removal of the posts, such evidence had been obliterated, either through cultivation or by natural processes.

Most of the stockade posts were missing, and those found were largely in two continuous, but separate sections. Although no record was made of the post ends found in 1931, Blackford's description of their discovery furnishes a rough idea of their position, and it would now seem that they stood in a more-or-less continuous line, thus making in all three such sections of post ends (Fig. 21).

At the top of the stockade trench, and directly over the two sections of post ends uncovered in 1953, were found charcoal and burned earth. The charcoal was in very poor condition, but it definitely constituted the remains of vertical wood members of the same size and shape as the lower water-preserved post ends (Fig. 17). The earth in the vicinity of this charcoal was burned hard and red, showing that the posts at these points had been burned while still in place. In addition to the charred remains of the standing posts, charcoal was also found scattered out a short distance from the stockade trench. This might have been interpreted as charcoal scattered from the charred posts through cultivation, except for the fact that the earth under this scattered charcoal showed evidence of exposure to heat. In addition to the burned sections above the preserved post ends, charcoal and burned earth were observed also along the top of the stockade trench at another point where no post remains were found (Feature 13). The charcoal in this instance, however, was lying with the grain of the wood horizontal. In every instance, the 3-inch cultivated or disturbed zone at the 1931 ground line extended unbroken over the stockade trench and over these burned areas.

The evidence is quite clear, therefore, that the French destroyed the stockade by pulling up about three-fourths of the posts, stacking them against the three standing sections of the stockade, and then burning them. In addition, some logs were burned in separate piles, such as represented by Feature 13. Almost certainly the posts would not have been consumed entirely, and this would account for the fact that Col. Burd could still see the remains of a circular stockade when he visited the site five years after the battle. Gradually the above-ground remains disappeared (which they apparently had by the time of Lewis' visit in 1816), leaving about 2.0 to 2.5 feet of post in the ground, the upper few inches of which had been charred by the fire, Some of the charred section lasted through the years, along with the lower ends that were below the ground water line, while the portion between gradually rotted away. This was the condition discovered in the excavations, as shown in Figure 22. Since the charcoal and burned earth did not show up in the 3-inch surface zone, it would appear that this layer had been disturbed after the fort was burned. The only explanation is that the area had been cultivated, but probably no more than a disking to improve the pasture. In his claim that the fort site had never been cultivated, Mr. Fazenbaker apparently meant that it had never been plowed and planted to crops, and the archeological evidence seems to bear this out.

Scattered along the stockade trench were a few ends of posts, lying horizontally or at an angle, not vertically, with the exception of a single large gate post, described later. Six such fragments were found, and presumably represent posts that had broken off when the stockade was torn down, or isolated posts that were partly pushed over, but not removed and burned with the majority. As with the vertical remains, these odd pieces rotted away, except for the portion below the ground water level.

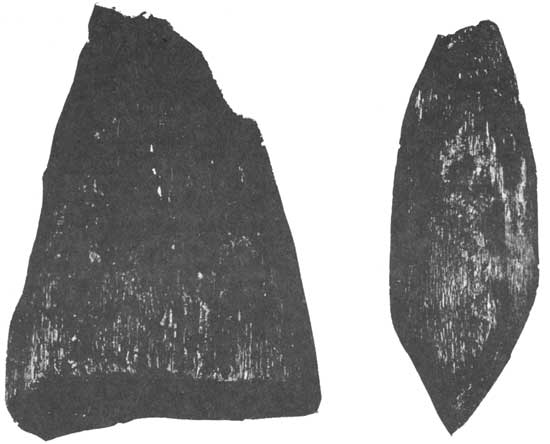

The stockade had been built with logs of white oak (Quercus alba L.), split in two, with the split, or flat, side facing out. The original logs ranged from 7 to 13 inches in diameter; the majority 9 or 10 inches. The lower ends show the original ax cuts, some cut nearly at right angles to the log, and some quite slanted (Fig. 23). Some bark remained on most of the posts, and there is no reason to assume that any of the logs were peeled before they were split and set in the stockade trench.

|

| Fig. 23. Typical water-preserved stockade post ends. Split post on left, unsplit "filler" post on right. |

In addition to the large split posts, small unsplit logs were used along the inside of the stockade wall. These were mostly about 5 inches in diameter, and seemed to have been distributed quite at random. They probably were used largely as fillers behind large cracks, although shorter ones possibly served as gun rests at the bottom of loopholes. Judging from the number of posts found in the two undisturbed sections, it is estimated that approximately 150 split posts and 50 to 75 small round posts were used in the original structure.

It was a distinct surprise to find split posts in the stockade, for such a practice, to my knowledge, was not common, and, in fact, its use at Fort Necessity may be unique. It is easy to rationalize that a flat surface would be better than a round one as protection from musket fire, and it is obvious that if split posts were used, the flat side would be faced outward. Even though this sounds quite plausible, it is possible that defense against enemy fire was not the full reason for the logs having been split. When the stockade was erected Washington had only about 160 men to cut and carry the logs to the fort site, dig the stockade trench, erect the posts, and build entrenchments, all within a period of less than five days. [16] In fact, there must have been considerably fewer than 160 men available to work on the fort, for some were out on scouting parties, some were taking the French prisoners from the Jumonville skirmish back to Wills Creek, and some undoubtedly were indisposed for one reason or another. Thus, the number of able bodied men available, as well as the need for great haste, accounts for the small size of the stockade and possibly, too, for the use of split logs. It was quicker and easier to split a log than to chop down another tree and cut off a log of the right length. Moreover, a full oak log of this size would weigh at least 300 pounds, whereas a split one could be carried from the woods and erected quite easily by two men. Even the archeological evidence, therefore, or at least the interpretation of that evidence, bears witness to the appropriateness of the name "Fort Necessity".

Only one break was found in the stockade trench. At a point on the west side there was a space exactly 3 feet wide where the trench had not been dug. At each side of this break the trench had been extended out in the form of a T (Fig. 21). The preserved end of an 11-inch round post was found at the center of one of these T's (Fig. 19), but all other stockade members were missing in this vicinity. The shape of the trench, however, suggests that there had been three round posts at each side of the opening, which almost certainly formed a gateway.

Every writer on Fort Necessity, and everyone who has drawn a map of the surface remains, real or imaginary, assumed that the stockade had been built partly over Great Meadow Run to provide a ready source of water for the men stationed within the fort. Blackford's record of the trace of the original channel, still partly visible in 1931, suggests that the stream had been very close to the stockade, but possibly did not extend into it. To check this, a test trench was excavated at the side of the circle nearest the stream. Archeological evidence here showed quite clearly that the circular stockade had been erected right up to the stream, but had not extended over it.

It is possible that a second gate was located at the rear of the stockade to provide access to the stream, or a surface well may have been dug against the inner side of the stockade wall at the closest point to the stream. But what provision, if any, was made for a water supply inside the fort will never be known, since the ground in this vicinity was disturbed to a depth of over 3 feet during the earlier excavating. Of course, if every square foot of the site had been excavated, evidence of a well — if one had existed within the fort — would have been found.

Although the 1953 excavations produced considerable evidence as to the method of constructing the stockade, there is no way of determining the length of the posts. Large, permanent stockade structures, such as Washington saw at Fort Le Boeuf, made use of whole, squared logs, pointed at the top, and often extending as much as 12 feet above the ground. The makeshift structure at Great Meadows would certainly have been lower, but that is about all we can say as to its height. Loopholes would probably have been provided by separating adjacent split logs and placing a short round log behind this opening, with the top of the filler log about 4 feet above the ground. This would account for some of the round poles, while others approximately the length of the main posts would have served to fill normal cracks. Except for the use of split logs, this method of constructing a stockade is shown in military manuals of that period.

The Storehouse

According to Shaw, there was a crudely built storehouse, covered with bark and hides, in the center of the stockade, Presumably it was made of logs or split planks, as he states that men were wounded during the battle by splinters knocked from this structure. Although built for the storage of provisions and ammunition, it is said that the storehouse was used during the battle as a first aid station. [17] Shaw said that this building "might be 14 feet square" but he said also that it was 8 feet from the stockade wall. [18] One of these figures obviously is wrong, since the stockade is known to have been 53 feet across. The 8-foot dimension is less reasonable than the 14-foot storehouse, as 14 feet would seem to be about the maximum size for a small storage shed. It is quite possible that an error was made in recording Shaw's deposition, and that he had said 18 feet, rather than 8. This figure would fit the requirements very nicely.

Even though the space within the stockade circle had been disturbed considerably in 1932, much of this area was explored in 1953, primarily in search of some indication of the storehouse size and orientation. No positive evidence was found, but this is not surprising, as the structure must have rested directly on the ground. In one of the exploratory trenches a change in the character of the original upper soil layer was noted. Although the edge of this soil change could be followed but a short distance because of recent ground disturbances, its location and orientation was suggestive. It was at right angles to the line of the gate and 8 feet from the exact center of the stockade, thus coinciding rather closely with 14-foot dimension for the storehouse. Suggestive as this is, it is really too vague to consider as acceptable evidence for the location and size of the original structure.

One discovery outside the stockade may have some relation to the storehouse. This was a log found at the bottom of the entrenchment ditch (Fig. 24). The log has a diameter of nearly 9 inches at the butt, and is exactly 13 feet long, with ax cuts on both ends. Being a whole log, it obviously was not used in the stockade, unless as one of the gate posts. It might have been a wall or roof log from the storehouse or a log reinforcement along the top of the entrenchment. The former probably should be ruled out, since this log, although of approximately the right length, is not notched or shaped in any way.

|

| Fig. 24. Log, 13 feet long, found in bottom of inner ditch of earthworks. |

Lacking archeological evidence, we can only surmise that the storehouse was probably a very crude log structure. Since it was intended as a storehouse for powder and provisions, it would have been of fairly solid construction, even though hurriedly and crudely built. It may well have had a relatively flat, shed roof, as suggested in the conjectural reconstruction shown in Fig. 38. The bark and skins mentioned by Shaw would have been laid on small branches placed close together across the sloping roof logs. The building would have had a fairly rugged door, probably of split planks. It would have been windowless, with a dirt floor.

Other Features Associated with the Stockade

No features that can be associated with the construction of the fort, or with its occupancy, were discovered inside the stockade. The only evidences of fires were the burned areas along the line of the stockade, and these can only be explained as incident to the final destruction of the fort. Since ammunition was stored in the storehouse, remains of campfires would not be expected in, or near, this structure, although it would seem quite probable that the men, clustered inside the stockade on the day of the battle, might have built small fires close to the stockade wall.

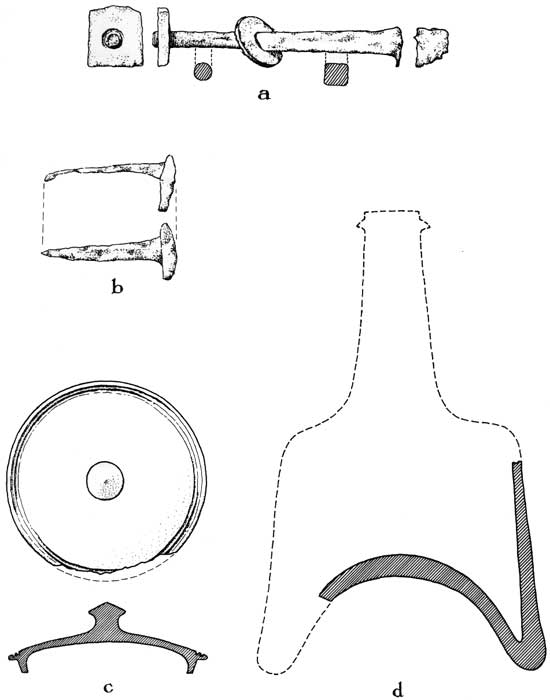

No metal objects were recovered which definitely can be identified as having been used in the fort structures. An iron bolt was found just above the remains of the large round gate post, and may have been used in some manner in framing or hanging the gate (Fig. 28). On the other hand, it is more likely that this bolt came from one of the wagons which were destroyed, with the fort, by the French. Both the stockade gate and the storehouse door probably were supported on wooden pins and secured with wooden bars and other improvised fasteners.

A few iron nails were found scattered about the area, but there certainly were not enough in the vicinity of the storehouse to suggest that nails or spikes were used in its construction. Those that were found very likely came from wagons, chests and boxes that were destroyed with the fort.

The Entrenchments

No less important than the discovery of the stockade remains was that of the entrenchments. Limitations of time and funds prohibited the exploration of the entire length of the trenches, and probably the only value of their complete excavation would have been the recovery of additional objects, particularly musket balls. The first exploratory trenches crossing the line of the entrenchments revealed that the original ditch lay inside the 1932 concrete footing. Fortunately, the reconstructed stockade was placed along the crest of the original parapet or breastwork.

After the ditch as disclosed in the first three cross trenches had been carefully plotted, it was apparent that Blackford's survey provided an accurate record of the entire ditch location, except for the missing section on the east side. Cross trenches were dug at points where Blackford's map showed a change in course of the ditch, as well as at the ends adjacent to the circular stockade. No attempt was made to locate the ditch at Corner "C", since evidence from the previous season's work indicated that the rock fill of Fazenbaker's lane would have destroyed all remains of the entrenchment.

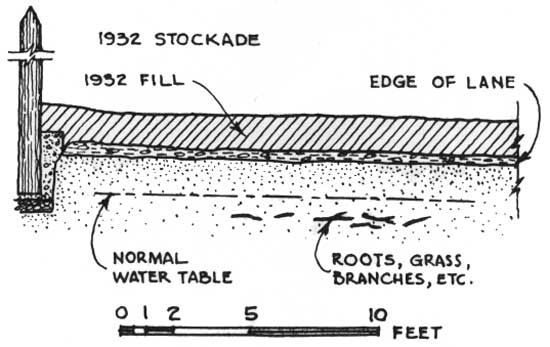

The various cross trenches showed that the ditch was fairly uniform in section. It had been dug about 2 feet below the 1754 grade, which took it down to the level of the normal water table (Fig. 25). In spite of the 1932 disturbances, it was possible to determine the exact shape of the original ditch, which, in turn, permitted an accurate reconstruction of the entire entrenchment.

|

| Fig. 25. Typical cross-section through 1932 stockade and across line of 1754 earthworks. |

Observations at the site through the years indicated quite definitely that there had also been a ditch along the outside of the parapet, but probably not as deep as the main ditch. [19] Previous excavating and grading on the outside of the ridges made it difficult to obtain a clear picture of what the original situation had been. Apparently a relatively shallow ditch had also been dug adjacent to the toe of the parapet along certain portions of the entrenchment. Customarily, such a ditch was not dug in constructing a simple shelter trench, but there are obvious reasons for its use at Fort Necessity, which will be discussed later.

The ends of the ditches adjacent to the circular stockade were found, as well as a gap at one corner, this opening obviously providing the main entrance into the entrenched area. There is a possibility that some sort of a detached breastwork or even a palisade was placed outside this opening, but it was not feasible to explore this area during the 1953 field season. Except for the opening at one corner, the evidence from previous surveys and archeological excavations shows that the earthworks formed a continuous line of defenses protecting the side of the stockade facing the road, or trail, some 180 yards distant. It had been calculated correctly that any enemy attack would come from this side due, presumably, to the proximity of both the trail and the woods.

Quite a few lead musket balls were found in the back slope of the inner ditch; otherwise relatively few objects were recovered from exploration of the entrenchments. The 13-foot log, previously mentioned, was found near the stockade end of the north ditch, with a small round post, 3.4 feet long, lying beside it. In the earth adjacent to these logs were found fragments of clay tobacco pipe stems, several lead musket balls, and four gun flints.

With the location and width of the parapet delimited by the outer and inner ditches, and the amount of earth used to form the parapet determined by the cross-section of these ditches, the original shape was not difficult to reconstruct (Fig. 26). The inner slope would have been relatively steep, probably approximately the slope of the ditch wall immediately below it. Many writers have stated, or suggested, that the breastwork was reinforced with logs. It is not improbable that logs were imbedded in the parapet near the top of the outer slope, particularly in view of finding the 13-foot log in the bottom of the ditch, although one log was insufficient evidence from which to conclude that logs were used along the entire breastwork. Moreover, there seemed to have been enough earth from the two ditches to form a parapet high enough to conform to requirements for a simple shelter trench.

|

| Fig. 26. Cross-section (parapet conjectural) of 1754 earthworks and earthworks constructed in 1953. |

In constructing the breastworks, digging in the inner ditch would have stopped when ground water was reached. Since, upon reaching the water table, additional earth would be needed to bring the parapet up to the required height, either the ditch would have to be widened or earth supplied from the outside. Simple shelter, or field, trenches varied considerably in design, often depending upon the time available to build them. A good height for the parapet was 4.5 feet above the bottom of the ditch, which would provide protection for reloading by stooping down, and the proper height for resting the barrel of the gun when firing. A parapet six feet high was even more desirable, but this would have required a firing step. Such a design would not be expected in a simple, hastily constructed work, nor was there sufficient room as the ditch did not have width enough for even a narrow firing step. Assuming, too, that the main ditch did not provide enough earth to bring the parapet up to the required height, additional earth could have been secured most easily from the topsoil layer just outside the parapet.

There is good evidence that an attempt was being made to improve or extend the fortifications on the morning of the French attack. Washington reported that "as our Numbers were so unequal, we prepared for our Defence in the best manner we could, by throwing up a small Intrenchment, which we had not Time to perfect. . ." [20] It might seem from this reference that the "small Intrenchment" was distinct from the major earthworks constructed a month earlier. Almost certainly Washington was referring to the completed, larger works when he stated that his troops "drew up in Order before our Trenches" when the French approached. [21]

The archeological explorations throw no light on the problem of how much, or which part, of the entrenchments were built during the first period of construction, or the portion which may have been built just before the battle. Nor did the explorations reveal any supplementary works, either outside or inside the main line of entrenchments, although it is possible that this last-minute effort was so scattered, or so superficial, that evidence of it was missed in the test trenches.

There can be no question but that entrenchments were constructed during the first flurry of activity immediately after the Jumonville incident. Washington stated quite definitely that the entrenchments had been completed early in June, and that they were considered suitable for defense against any conceivable attacking force. [22] These entrenchments, with the stockade, were built in great haste, and for a specific emergency. They were designed to accommodate the force at Great Meadows, at the time less than 160 men. With the coming of additional troops during the following few weeks, bringing the total force to around 400, no thought apparently was given to enlarging the fortifications. Since Washington considered the first entrenchments properly constructed for defensive purposes, although by a smaller garrison, it would seem that the activities interrupted by the attack on July 3 most likely consisted in extending, rather than modifying, the existing entrenchments. It is reasonable to conclude, therefore, that the system of earthworks represented by the ridges and depressions, and more definitely delimited through archeological explorations, is the final enlarged line of entrenchments.

Another troublesome problem is accounting for the disposition of some 400 men during the battle. The main camp area, possibly located in the meadow upstream from the fort, would have been abandoned with the first warning of the French approach. We know that the horses and cattle were left outside the fort, for it is recorded that one of the first things the French did was to kill these animals. [23] If the fighting strength was only about 300 men, as Washington claimed, the rest of the troops, many of whom were sick, must have been packed within the circular stockade. [24] Some may have huddled outside the stockade on the side away from the line of fire, or in sheltered spots along the stream bed. The main fighting strength was stationed in the entrenchments, but, at best, not over half the force could have fought effectively from the earthworks. The stockade might have served some 50 fighters, and a number of men, of course, were involved in various other activities, such as caring for the wounded. It is quite obvious, therefore, that the defenses at Fort Necessity were badly designed for use by an army of 400 men, and that undoubtedly the fort could have been defended more easily with half that force.

Great Meadows Run

One of the main objectives listed in the plans for the first season's explorations was to determine the exact location of the pre-Fazenbaker channel of Great Meadows Run. However, as we learned more about the physical conditions at the site, and when Blackford's original survey records were made available, this phase of the project was given up. Moreover, one of the principal reasons for determining the original stream location was to have just that much more information on which to interpret the documentary data and to appraise the previous interpretations.

It had been said by several writers that spring floods caused frequent changes in the stream's channel. This claim apparently had been advanced in support of certain theories as to the fort's original shape and to explain the absence of the ridge and depressions near the Run. Once the true situation had been determined, the exact position of the stream in 1754 was no longer of any great concern.

One trench was excavated at the back of the original stockade, as mentioned in the discussion of the stockade's location in reference to the Run. Evidence here showed that the banks of the stream channel prior to its straightening were not particularly steep, and presented a profile which one could assume would have withstood normal flooding conditions. It would also seem a reasonable assumption that Blackford's survey shows correctly the stream bed location prior to its straightening by Fazenbaker (Figures 9 and 16). The channel change by Fazenbaker took place only about 100 years after the battle, and there is no strong reason to believe that the old trace mapped by Blackford is too different from its 1754 course.

FURNISHINGS AND EQUIPMENT

General Comments

Very little can be learned from the records as to the military equipment, tools, or personal furnishings of the armies at Great Meadows. Archeology adds some information, but not a great deal. Accounts by early travelers passing the site speak of seeing swivel guns lying about, but even these were finally carried away. [25] Undoubtedly the Indians, as well as emigrants traveling the Braddock Road, salvaged all usable objects and picked up other things simply as trinkets or souvenirs. Owners of the property and later visitors probably recovered an occasional relic and a number of items exhibited in the Tavern are said to have been picked up on the fort site or in the surrounding meadow or woods.

From some of Dinwiddie's letters written just before Washington set out from Alexandria, we might formulate a list of things considered desirable or essential for such an expedition. There is no evidence, however, that these items were assembled, and, in fact, one might judge from Washington's numerous complaints, that many of them were never furnished. Except for the officers, the Virginia Regiment undoubtedly was poorly equipped, although the South Carolina company would surely have been in regular army uniforms and properly armed. From scattered references, as well as from inference, we can be reasonably certain that there were wagons, horses and riding gear, axes and shovels, pickaxes and spades, and other tools needed in felling trees, erecting structures, and building roads. There would have been medical supplies and equipment, utensils for storing, preparing and eating food, tents and blankets, casks for the rum, and personal items, such as tobacco pipes.

For the present report to be complete, I probably should analyze all documentary references and describe in detail the most likely tools, equipment, and furnishings that would have been used or stored at Fort Necessity. However, I am leaving for some future student with special interests and knowledge of the subject the task of providing such inventory and description. I will confine my discussion of artifacts to those found in the excavating, relating them, where possible, to documentary references.

Weapons

Small Arms

Small arms, in contrast to cannon, would have been taken for granted, whereas powder and shot would have to have been provided in considerable quantity and issued to the men as needed. That is why the latter appear more frequently in the records. A man's musket posed no problem of transportation and would have been the last thing he would have relinquished. In various letters written in connection with preparing for the expedition, Governor Dinwiddie mentions equipment required, including "300 small arms, powder and shott". [26]

There are other indirect references to powder, but no mention of arms. Probably almost every man carried a musket, and some of them, if not all, were equipped with bayonets. [27] The officers would have carried swords and, in some instances, pistols.

Of the objects found in the excavating, very few relate to small arms. One interesting item is the brass tip of a sword scabbard of the type used with a typical British infantry sword of the period (Fig. 28). Probably the most common items in this category are the numerous lead balls and shot. These are of several sizes and, of course, include both French and English ammunition.

On the whole, the lead balls fall into two size groups, the larger ranging from 66 to 73 caliber, the smaller from 52 to 60, as shown in Table 1. Measurements, of course, are not true indications of original sizes, since there is considerable corrosion and often slight deformation, Because of the corrosion and irregularity of the balls, measurements were made only to the nearest 0.02 of an inch. Balls flattened from impact with a hard object are not included in the table.

Table 1 Lead Musket Balls

| Caliber (approximate) |

Average Weight (ounces) | Number of Specimens | ||

| Group A — | 1 | 52 | 0.47 | 9 |

| 2 | 54 | 0.52 | 12 | |

| 3 | 56 | 0.56 | 10 | |

| 4 | 58 | 0.61 | 9 | |

| 5 | 60 | 0.66 | 3 | |

| Group B — | 1 | 66 | 0.92 | 19 |

| 2 | 68 | 1.00 | 27 | |

| 3 | 70 | 1.05 | 20 | |

| 4 | 72 | 1.25 | 2 | |

There were probably at least three different caliber muskets represented, 54 or 55, 69, and 75. The smallest balls (A-1 and A-2) could have been intended for either rifles or pistols.

All flattened balls (29 in number) fall in the small group, their weight being around 0.50 ounces. They were found mostly along the stockade trench, where they apparently had dropped after striking the stockade. This is in agreement with other evidence that the French muskets of that period were a smaller caliber than the British.

Several musket balls were found imbedded in the back slope of the entrenchment ditches, and a great many undoubtedly would have been recovered if more of the ditch had been excavated. The British troops must have left fairly large quantities of ammunition at the fort, and we know that they broke the powder casks and scattered the powder about so that it could not be used by the French and Indians. This would account for a greater number of larger size balls being found, although if the entire fort site had been dug, and the earth carefully screened, it is possible that the smaller French sizes would have predominated.

Several blobs of lead, found in the stockade area, showed evidence of having been in a fire. Since the weight of each of these is about that of an average musket ball, they are probably balls that were imbedded in the logs of the stockade or cabin, and melted when the logs were burned by the French.

A "cache" of small lead shot was found in 1932 when digging a drain tile trench in the vicinity of the reconstructed cabin. This deposit totaled 610 shot, ranging in size from 0.08 to 0.22 of an inch in diameter, the majority falling between 0.14 to 0.18. These "bird shot" may well have been for hunting birds and other small game. In the same deposit were 10 larger shot measuring 0.24 to 0.36 of an inch, which is in the "buck shot" range. Except for this single concentration, relatively few shot of these smaller sizes were found.

Of the guns themselves, not a single fragment was found. Sixteen gun flints, however, were recovered, although they tell us less about the guns than do the lead balls. (Fig. 27). Since they mostly came from within the stockade area, or from the entrenchments, we can assume that they were from muskets of the Virginia or Carolina troops, rather than the French.

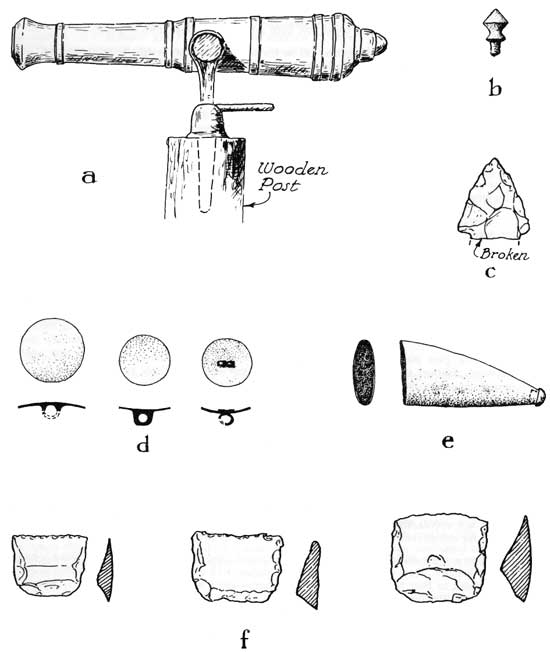

|

|

Fig. 27. Military Specimens. a. Swivel gun typical of the 1/2 pounder type probably used at Fort Necessity. (1/8) b. Brass fastener. c. Indian arrow head. d. Brass buttons. e. Brass tip of sword scabbard. f. Typical gun flints. Objects b through f were recovered in the excavations. All are 3/4 life size. |

Cannon

Not until June 9, with the arrival of reinforcements bringing 9 swivel guns, did Washington have any weapons other than the small arms carried by the troops. [28] These small cannon, however, are mentioned more often in the records than all other military equipment combined. Washington quite obviously looked upon this armament as important in the defense of Fort Necessity, should the need arise to make a stand there. This is reflected, for example, in preparations made on June 12 for an anticipated attack. Through a misunderstanding of intelligence from a scout that a large force of French was approaching, Washington "ordered Major Muse to repair into the fort, and erect the small swivels for the defence of the place, which he could do in an hour's time." [29]

There is other evidence that great stock was put in these cannon, although they turned out to be a distinct liability. They were lugged over the mountain trail during the late June expedition, and then carried back to Fort Necessity when the pack horses could better have been used for transporting the sick and tired troops.

When the French attack finally came on July 3, these "small swivels", on which Washington had relied so heavily, proved quite ineffectual. According to the French commander's report, the swivel guns were used only at the outset of the battle, and then with little effect. He described the action as follows: "As we had no knowledge of the locality we presented our flank to the fort whence they began to fire cannon on us . . . The fire was very brisk on both sides . . . We succeeded in silencing (so to say) the fire of their cannon with our musketry". [30]

Shaw's description of the battle mentions only two swivels, which is probably all the troops had time to set up. [31] It is very doubtful if there were any prepared gun emplacements or protected battery positions. The two swivels were probably mounted on wooden posts or blocks set in the open area between the stockade and the trenches. In addition to Shaw's reference, another participant, Major Stephen, reported that a section of the stockade was removed during the later stages of the battle so that swivel guns could be fired from within the stockade. [32]

On the day after the battle, according to Villier, "M. de Mercier caused the cannon to be broken, as also the one granted by the capitulation, the English not being able to take it away." [33] These "broken" (spiked?) guns must have been left lying about the site, and were probably among the very few things the Indians did not salvage, although Col. Burd reported seeing only two iron swivels when he passed there in 1759.

Except for the number of guns, all we can glean from the records is that at least two were of iron, which we learn from Burd's accounts. Archeological evidence, however, in the way of iron balls, furnishes a clue to the size of these swivels. Altogether, 12 iron balls were recovered in the various excavating activities, and they almost certainly were for use in Washington's nine swivel guns, since the French would certainly not have brought cannon all the way from Fort Duquesne.

Nine of the 12 balls were roughly 1.5 inches in diameter and weigh 7 ounces each. Three iron balls are a smaller size, about 7/8 of an inch in diameter, and weigh only 1-1/4 ounces. The guns for which these two sizes of balls were intended are difficult to determine, since the balls are badly rusted. The larger size was probably for 1/2 pounder guns. In addition to firing iron balls, "scatter" or "case" shot was also used in guns of this type. Such shot could have been either the larger musket balls, or the small pistol size.

Swivel guns of even the larger size could have been carried quite readily by packhorse, or in the wagons. Although such guns were sometimes mounted on galloper carriages, it is not likely that carriages were used in the 1754 expedition.