|

Fort Union

Historic Structure Report |

|

| PART I |

Chapter III:

"PRIMITIVE LOG HOUSES . . . CHINKED AND COVERED WITH EARTH"

The Beginnings of the First Fort. The year was 1851. New Mexico had been a United States Territory for a year. Herman Melville had just published Moby Dick; and Nathaniel Hawthorne had just completed The House of Seven Gables. In New York, the New York Daily Times, which later became the New York Times, was founded. The nation's first pictorial magazine, Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion appeared in the parlors of better homes. American textile mills were switching to steam power. In New Orleans, a group of Spanish refugees and American southerners were planning an expedition to Cuba in hopes of starting an uprising against Spain. It was during this year that Lt. Colonel Edwin Vose Sumner of the 1st Dragoons established Fort Union, New Mexico, on July 26.

When the Army moved in to the area of Fort Union in 1851, the first order of business was construction of temporary shelters while the more permanent ones were under construction. Also, the army considered its position in terms of subsistence because of the numbers of animals it supported. A report prepared in August, 1851, summarized the resources of the area. Corn and hay were available for purchase, and the grazing around the post was considered very good during the summer and fall. The report noted:

There is sufficient building materials near the post for all purposes, consisting of a very fine white sand stone, clay for bricks and adobes and pitch and spruce pine in the mountains from 9 to 30 miles of the Post. All other articles required for building would have to come from the East, as they are not produced in this Department . . . The greatest objection to this point as a military post is the want of running water for stock . . . The only possible mode of transportation in this section of the country is by land . . . The usual and only transportation used here are wagons, carts and pack mules. [1]

The new soldiers and families at Fort Union arrived during the late summer. With fall and winter fast approaching, construction of quarters was the first order of business. Captain Isaac Bowen and his wife Katherine were among the early arrivals to Fort Union. Katie and Isaac wrote home frequently to her family, and her letters provided a very graphic picture of life in the early days of Fort Union. The new occupants lived in army tents while the buildings were under construction. Katie Bowen noted that the location of Fort Union was well suited to farming operations, had an ample water supply, and was surrounded by hills covered with pine trees with a supply of wood so good that it would "not fail in thousands of years." At the time she wrote that statement, she also noted that the hospital, company quarters and the commander's quarters were nearly completed, that Major Sibley's quarters were started, and theirs were next. Although houses were built in priority sequence according to rank, the commanding officer of the post had ordered that all the married officers' quarters should be built first. [2]

The Bowens began their life at Fort Union by living in one army tent, but soon they expanded into three attached tents of double thicknesses of duck. They cooked their food outdoors on an open fire, and ate their meals in a "bower" that was wet at times. [3] Charlotte Sibley, the wife of Major Ebenezer Sprote Sibley described her temporary tent quarters when writing home to her family. She wrote: "Our tents are put upon frames and are floored and carpeted. I have arranged them so that the word cozy would more properly apply in description of the interior than any word else." [4] The tents they spoke of most likely were the wall tents discussed in the previous chapter.

In early September, 1851, Major E. S. Sibley wrote to the Quartermaster General in Washington because he was concerned that the new post did not have enough stores of grain to get through the winter. Also, he increased by half an estimate that Colonel Sumner had sent in earlier for building materials. The estimate requested stationary, horse and muleshoe nails, horse equipments, scythe stones, rope, wagon timber, 2 kegs of #10 nails, 1 keg of #12 nails, 1 keg of #20 nails, 2 boxes of 7 x 9-inch window glass, 1 box of 8 x 10-inch window glass, and 15 pounds of putty. For tools, he requested felling axes, axe handles, spades, shovels, stone masons' hammers, stone masons' sledges, bricklayers trowels, and mattock handles. [5] That list of requested materials probably meant: 1) that some of the buildings were not receiving stock windows and some of the windows were being custom-made to fit buildings; 2) that logs used in construction were not hewn (otherwise adzes, too, would have been on the list of tools; 3) that stonework for building construction was common.

A letter to the Quartermaster General the following day stated:

We are progressing rapidly in the erection of buildings at this place & have already raised log cribs for quarters for two companies, one of Infantry & one of Dragoons, for a hospital & quarters for the commanding officer of the post & three staff officers—I have found limestone in our immediate vicinity which having been tested proves of good quality & I have had a kiln made which will be filled & burnt immediately—as soon as the mill which is now being built is in a state of readiness to saw lumber which will be the case I trust tomorrow. We shall commence covering the buildings & laying the floors & if no accident occurs I expect the quarters will be in readiness to receive the troops by the 1st day of November next at furthest. [6]

By mid-September, 1851, the quarters were still under construction. Besides gathering raw building materials from the surrounding landscape, the troops and the handful of civilians at Fort Union were expected to supplement their own rations through subsistence—growing their own vegetables, making butter, and even having a few animals. Because of all of the time devoted to survival on the frontier, building construction took longer than anticipated.

As the late fall and then winter approached in 1851, Katie Bowen was still concerned about the slow construction of the quarters. The fort residents built fires in front of their tents to keep warm. As they stood around those fires warming themselves, they watched the stone chimneys going up on the new rough buildings. Katie Bowen noted that the chimneys on the hospital and company quarters were drawing well and throwing out lots of heat. She approved of the overall quarters design. Also, she noted that their room allotment for that winter would be three rooms for each officer, either 18 x 18 or 18 x 20. [7]

By the beginning of October, 1851, log cribs were completed for quarters for two staff officers, the department commander, and two company captains. The commanding officers quarters had a roof, and the Dragoons' quarters were in the process of getting one. The letter complained that the sawmill was constantly breaking down and the saws kept wearing out. Because of those delays, they were compelled "to cover the officers quarters with earth, the custom of the country." The rough, unpeeled log buildings went up slowly. [8] At that point, the staff thought that the only buildings that would get board roofs during the winter of 1851-1852 were the company quarters and the hospital. The earth coverings were considered temporary, and were meant to hold through the winter until spring, 1852, when the lumber supply would be adequate enough to cover the remaining buildings. [9]

By December, 1851, the quarters were still short of completion, but the availability of boards for roofs and floors had improved. A progress report noted:

The quarters for one company & the hospital are completed except the glazing of the windows, & the hanging of the doors, & I am now busily occupied in sawing the lumber necessary to cover the other set of soldiers quarters. —The officers quarters are all covered and, with a few exceptions, floors are laid in one room of each set and the quarters are occupied by officers & their families. [10]

The quarters were not fully completed, but work on them had gotten to the point where the structures were considered suitable for winter shelter. The hospital, however, did "not exactly answer the purposes for which it was intended, another building will at once be erected & the present one will be converted into store houses to cover the public stores which are now in tents, as they have been since the establishment of this post." [11]

First Fort Occupancy. By April, 1852, Major E.S. Sibley reported to his superiors that with the exception of a few shops and a storehouse, all of the buildings had been erected and were in a relatively habitable condition. He planned to finish them completely and as rapidly as possible using the labor of the enlisted men he had. He also said that "I hope by the close of the ensuing summer to be able to announce to you that everything has been done that was originally contemplated & agreeably to the original design." He boasted that with the exception of a small quantity of lumber, all of the timber was sawn at the post. Also, he was "having both lime & coal burned thus providing the necessary materials with enlisted labor & reducing to some extent the expenses of the Quartermaster Department in this Territory." [12]

One year later, the first Fort Union was operating fairly efficiently in its physical plant. A summary of the fort in September, 1852, described the fort buildings as follows:

Nine sets of officers' quarters (HS-126 through HS-132, and HS-134 and HS-135); each set—with one exception, which is composed of three rooms and a kitchen—eighteen feet long and fifteen feet wide. These quarters have earthen roofs; and five of them have, in addition, board roofs. The other sets of quarters will also be covered with board roofs, as soon as lumber for the purpose can be sawed, and it can be conveniently done.

Two barracks (HS-138 and HS-139)—each one hundred feet long and eighteen feet wide, each two wings fifty feet long and sixteen feet wide; board roofs.

Hospital (HS-140)—forty-eight feet long and eighteen feet wide, with a wing forty-six feet long and sixteen feet wide; board roofs.

Storehouse—(probably HS-136) one hundred feet long and twenty-two feet wide, with a wing forty-five feet long and twenty-two feet wide; board roofs.

Commanding Officer's office and court-martial room—forty-eight feet long and eighteen feet wide; earthen roof.

Offices for assistant quartermaster and commissary of subsistence—thirty-eight feet long and eighteen feet wide, earthen roofs.

Smoke-house (probably HS-163)—one hundred feet long and twenty-two feet wide; board roof.

Guard-house and prison—forty-two feet long and eighteen feet wide; earthen roof.

Blacksmith's and wheelwright's shop—fifty feet long and eighteen feet wide; board roof.

Bakehouse (HS-159)—thirty-one feet long and seventeen feet wide; earthen roof.

Ice-house—twenty feet long and thirty feet wide; earthen roof, covered by a board roof.

Quarters for laundresses (HS-144)—one hundred and fourteen feet long and eighteen feet wide; six rooms; earthen roof.

In addition, yards to five sets of officers' quarters have been enclosed, and two corrals have been made, each one hundred feet square.

The lumber used in the construction of these buildings, with the exception of fourteen thousand eight hundred and seventy-two feet, has been sawed at this post. [13]

Organization and Function: Houses, Yards, and Post. The Bowen letters contained a great deal of information about the organization of the officers' quarters and their yards. The general layout had the typical army regularity and relative symmetry. Katie Bowen noted to her mother that their side of the garrison where the officers were quartered was known as "Aristocrats' Row."

When the Bowen house finally was completed, it contained a central hall that the family used for a dining room flanked by one bedroom and a parlor. They also had a kitchen, a store room, and a servant's sleeping room. [14] The central hall floor was covered with a small carpet. The building originally had a flat dirt roof, but the house had a gable roof of flat boards above the dirt by 1852. [15] Although the Bowens had brought a cook stove with them when they arrived at the fort, they did not have it set up and working in the kitchen until 1852. [16]

Katie Bowen noted that the winds at Fort Union were very strong. According to her, they blew hard for a week from the north, then quieted down, and then they blew hard from the south. She had trouble keeping the dirt out of her new house, and she wrote home that the dirt drifted in like snow into every unprotected crevice. Occasionally she even had to shovel out her house because it was so deep. Despite the ever-present dirt problem, she found her house "pleasant and comfortable as any I ever lived in. The rooms are well arranged and are large and [ceilings] very high." [17] But she also missed the comforts of her childhood home. She wrote to her parents: "How I would like that you could look in and see how primitive we are in our log houses, white-washed logs overhead, chinked and covered with earth to shed snow and rain." [18]

The yards at the officers' quarters contained multiple functions. Because of the necessity of supplementing army rations, the Bowens had cows, three pigs, at least one horse, chickens, and a team of mules. [19] Isaac Bowen built a "cow house," a barn, and chicken houses in their yard. The Bowens had started making their own hay rather than paying the quartermaster $20 a ton—which also meant they needed a place to store it. They had chicken coops in their yard and kept as many as 80 chickens at one time. [20] To conduct water away from the house when it rained, the Bowens dug large trenches around the foundation of their house. [21] They were in the process of making plans for small cellars in their yard for keeping milk, but records do not indicate whether or not any were constructed. [22] Although the post had a large, irrigated public garden for growing vegetables, the Bowens had a small garden plot in their yard for raising herbs for medicinal purposes. [23] Katie Bowen noted that all of the "outdoor work is done by the police party and a man in Isaac's department takes care of the horse, cows, pigs and chickens. The dog oversees the whole and watches at night." [24]

Because army rations on the frontier were inadequate, families and individual soldiers often took it upon themselves to supplement their allotment, as Katie Bowen did. The barter system was a significant part of daily life on the frontier, and families in particular traded and exchanged vegetables, butter, eggs, and herbs. The system was more of a social exchange than a true barter, but the families tried to provide each other with what they needed out of what they had available.

This reliance on supplementing army rations had an impact on the physical experience of the post. The troops often became creative in providing for extra food they needed by growing small garden plots and raising stock. In September, 1859, the post commander issued an order stating that from that time forward hogs were prohibited from running loose through the garrison. [25] The hogs ate anything they found and the troops in turn ate them.

The Army also provided its own grain. In 1861, the fort had an operating mill that crushed corn (location unknown). The quartermaster's office complained that the mill took three men and eight mules to operate it, but that it did grind corn from the ear. The post quartermaster complained that the army could already purchase shelled corn for about the same price, so he did not think it was worth the government's effort to use the mill. [26]

The fort also housed many non-military functions, some of which were of a transient nature, and so the first fort also contained a number of ancillary buildings. By March of 1853, a hot house (HS-164) existed, and Katie Bown noted that it was "a beautiful building, 50 feet long by 20 deep and the whole southern front of glass. A gardener's house (also HS-164) attached and fires kept night and day." The fort had two large ice houses for storing the ice needed during the summer months. [27] Bowen's enthusiasm for the hot house diminished six weeks later when she noted that the building had not been erected following "scientific principles" so it only yielded plants suitable for transplanting rather than full-grown ones. [28]

While Katie Bowen was concerned about the buildings that affected her domestic world, Military Storekeeper William Rawle Shoemaker was busy constructing the buildings he needed for his arsenal. In June, 1852, Shoemaker wrote to Colonel Craig, the chief of ordinance in Washington, ordering lightning rods (stems and conductors) for his buildings (HS-141). He noted that the highest points of his buildings did not exceed 20 feet in height, but that they covered "four sides of a square of 100 feet." He also wanted enough lightning rods for their future needs, since he was planning to extend the buildings. Also, his buildings were constructed in a fairly exposed location and they had no taller objects near them. Shoemaker was concerned about the prevalence of severe lightning storms in the area. He stated that he needed to construct a "larger & substantive" building for a magazine, but that its construction had been deferred until "after the other storehouses &c are completed." [29]

Shoemaker's request for a better magazine was approved, and in December of 1852, he requested permission to have some of the magazine and the wall surrounding it constructed by hired labor. He noted that making adobes and properly building with them could be best accomplished by hired labor since his own force was occupied with so many other duties. In the same letter he requested "fastenings & hinges suitable for a magazine with two doors and two windows . . . As the Magazine will be located at a distance from the other buildings, very secure fastenings will be required." [30]

Also in 1853, M.S.K. Shoemaker reported to the Assistant Adjutant General for the 9th Military District that his detachment consisted of 12 men "in the various grades of mechanics and artificers of ordnance, and in addition there is 1 hired armorer." Shoemaker had six of his detachment on detached service: one working the garden and five taking care of public animals. The remainder were "engaged in construction of shops and depot structures. [31]

Less than one year after the army moved in to Fort Union, other service-related businesses were well established in the vicinity. When the area of the reservation was declared eight square miles in 1852, an order went out to clear the reservation of all of its "shanties and grogeries" and the "keepers put in irons and sent to that town for trial." [32] Some of these "shanties and grogeries" were in caves in the cliffs in a canyon to the southwest of the fort. A high rate of venereal disease among the troops and large amounts of missing goods appearing in the "wastage or stolen report" for the first part of 1852 indicated that a vital subculture thrived in the vicinity. [33] Prostitution and black market trading were transient occupations that required only a modicum of shelter. [34]

Contemporary Descriptions. An 1853 inspection of the fort by Joseph Mansfield (see figure 1) noted some points about Fort Union and its location. Mansfield wrote that seven miles to the south of Fort Union was Barclay's Fort on the Moro River. The farm for Fort Union was about 23 miles north of the fort. He noted that the buildings for Fort Union were "of all kinds . . . as good as at any post and there seems to be enough of them to satisfy the demands of the service." He criticized the location of the fort, saying that it was too close to the mesa for adequate defense against the enemy unless a blockhouse were constructed on the mesa edge.

|

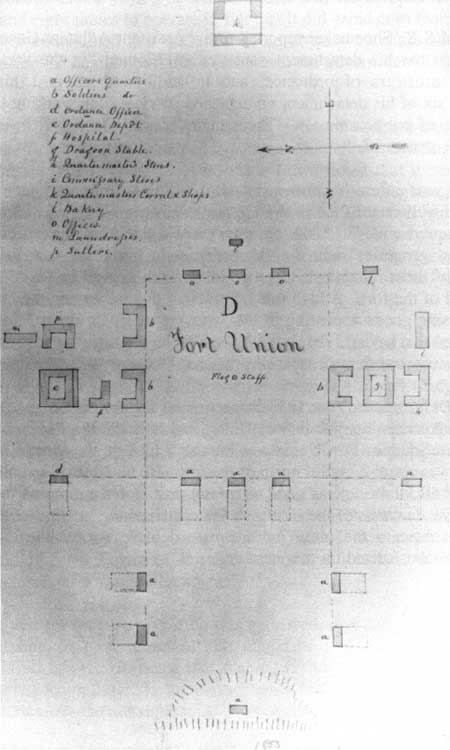

| Figure 1. This plan of the first Fort Union accompanied the 1853 Mansfield inspection report. The plan shows the principal structures and the layout of the fort at that time around a central rectangular parade ground. Missing are the small ancillary structures adjacent to the main buildings. Outhouses, chicken coops, small storage buildings, and small personal barns do not appear on this plan although they did exist. Also, this map should be considered a relatively schematic representation rather than a thorough plan. |

|

| Figure 2. This building, identified in the files at Fort Union as the first fort, was taken from the east-southeast about 1865. It is either HS-129, 130, 131, or 132. The building has no foundation, and the sill logs lie on the ground. The building has a board roof, gable-end chimneys, a log addition (kitchen) to the rear behind which is the stockaded fence for the yard. Katie Bowen described her house (which would have been similar) as containing a central hall, one bedroom, and a parlor for the principal rooms, with a kitchen, store room, and servant's room at the rear of the building, and servant's sleeping room attached. Museum of New Mexico. |

|

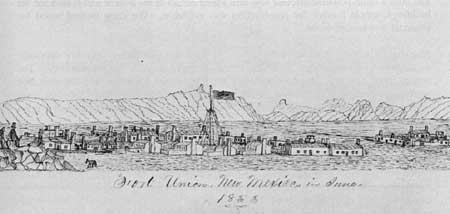

| Figure 3. This 1859 drawing of the first Fort Union depicts the general layout of the installation. The Commanding Officer's Quarters sat on a rise above the fort proper. Note the layout of the officer's quarters with their fenced yards, the paths and roadways connecting different areas of the fort. Of particular note is the Commanding Officer's Quarters on the left of the sketch. The ridge line and placement of the chimneys is different than that of the other structures, possibly indicating expansion between the time of construction in 1851 and this drawing (1859). Drawing by Joseph Heger. Arizona Historical Society. |

|

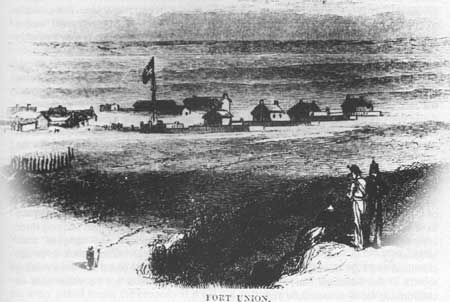

| Figure 4. This primitive sketch of Fort Union in 1853 appeared in A Cannoneer in Navajo Country: Journal of Private Josiah M. Rice, 1851. Although the sketch lacked the detail given by more accomplished artists, the drawing showed certain architectural features. On the right, some of the buildings retained flat, earthen roofs. Kansas Historical Society. |

Mansfield noted that the fort was the general supply and quartermaster depot for the department. Mansfield found the post "in a high state of discipline and every department of it in good order," especially when the troops had to do everything from building quarters, gathering timber and hay, farming, escorting trains, and pursuing Indians. The troops also cultivated a garden "which is irrigated by raising water by mule and hand power, and thus they are supplied with vegetables in part. A farm is also cultivated under the regulations established by the Honorable Secretary of War Conrad." The public garden was located by the side of the pond, and it had a six-horsepower pump to irrigate it. [35] Mansfield wrote about the good bakery, and how the quartermaster buildings were "as good as circumstances would admit." Because Major E.S. Sibley of that department had built a mule-powered circular saw mill which cut all of the boards and planks for the buildings, ample lumber for construction was available. The crew burned wood for charcoal and hauled wood.

Mansfield's report included information on M.S.K. Shoemaker and his ordnance department—responsible for all of the ordnance depot supplies for the territory. The report stated that the ordnance buildings for storehouses, quarters, and the gun shed were considered sufficient. Also, Mansfield wrote that Shoemaker had a six-mule team which he used in building construction. Shoemaker's ordnance outfit also had a good garden approximately 3/4 mile away from the fort which gave the men good vegetables. [36]

During 1853, a civilian named W.W.H. Davis visited Fort Union and described it as an "open post, without either stockades or breastworks of any kind, and . . . it has much more the appearance of a quiet frontier village than that of a military station. It is laid out with broad and straight street crossing each other at right angles. The houses are built of pine logs, obtained from the neighboring mountains, and the quarters of both officers and men work a neat and comfortable appearance." [37] Although Davis' view of Fort Union from a traveler's standpoint differed considerably from that of resident Katie Bowen, both views hinted at a fond attachment to the rustic fort: Davis enjoyed his first real view of civilization on the frontier after crossing the plains, while Katie Bowen struggled with daily life at the fort.

|

| Figure 5. This depiction of Fort Union showed the simplicity of construction of the buildings of the fort, along with the apparent regularity of the development around the flagstaff. This appeared in the W.W.H. Davis book El Gringo; or New Mexico and Her People, published in 1857. Davis visited Fort Union in 1853. |

Deterioration. The first Fort Union was built rapidly and with minimal concern for permanence. The fort underwent an inspection three years after its construction, and the report noted that most of the buildings were constructed in haste because autumn was setting in and the post commander wanted to house his men before winter. The report stated that the rough pine logs that were used in construction of the buildings still had their bark on, and many had begun to rot only three years later. By that time many of the buildings still had flat roofs covered with dirt, although some had board roofs over the dirt. When the logs rotted, the roofs fell in.

The report did concede that the buildings were in "habitable condition" for the two companies of the 2nd Dragoons and the one company of the 3rd Infantry that occupied them. Of note at the time of the inspection was a new stable constructed for the dragoon horses (HS-161). The building was 190 feet in length and 30 feet wide. It was made of "upright logs set in the ground with a sharp board roof. Also [constructed was] a large corral made with upright logs and plank gates for the preservation of hay probably [HS-184]." [38]

At the time the 1854 inspection was completed, a company of artillery was being transferred out of Fort Union and replaced with a company of dragoons. This meant that the fort needed a second dragoon stable. They intended to construct it to the same dimensions as the first, but to build it with a flat roof instead of a gable (plank-covered) roof. The transfer of the quartermaster and commissary depots to Albuquerque at about the same time freed up some space, but Fort Union remained a sub-depot to supply the northern posts of that department. [39]

Four years after construction had started, the post commander reported that "all the quarters of this Post want extensive repairs, many entirely rebuilding . . . a whole set of Company quarters were in a state of rapid dilapidation & the stables for one Company have to be rebuilt entire." Living at Fort Union at the time were 238 men forming three companies and one company of artillery, the latter of which was assigned there temporarily. [40] A year later a new commander, Bvt. Major Grier, took over the command and Fort Union and voiced similar concerns. He also stated that even making repairs to the buildings that they could, the structures would not be either safe or comfortable for even one more year. [41]

Conditions continued to deteriorate, and in the latter part of 1856 Assistant Surgeon Jonathan Letterman did an inspection report on Fort Union. He wrote that the fort was shut in on the east by the Turkey Mountains and on the west "by a precipitous mass of sandstone, about 150 feet in height." When the rains came, the run-off drained down the mesa sometimes with such force that the buildings were flooded. Letterman discussed how the building timbers and firewood came from six or eight miles away (the Turkey Mountains), and how the existing water supply was adequate although at times it gave people the runs. He estimated the area that the fort occupied as about 80 acres and that the fort presented "the appearance more of a village . . . than a military post." [42]

As far as the quarters were concerned, he described them as made of "unseasoned, unhewn, and unbarked pine logs, placed upright in some, and horizontal in other houses." He noted that the logs were decaying fast, and that his own house had decayed so much that the walls would not hold a nail. By 1856, one set of barracks had been torn down, and others were in imminent danger of collapse. But, he mentioned, the dangers posed by potential accidents from the collapse of buildings were "less awesome than the consequence from using the quarters which stood . . . for the unbarked logs afford excellent hiding places for that annoying and disgusting insect, the cimex lectularius [bedbug]." [43]

Conditions were so uncomfortable that troops often slept outside in the open air. Also, Letterman noted that all of the hospital rooms were wet, so the hospital staff had moved the sick to tents, and they laid out canvas to protect the hospital equipment. He concluded that the original fort was not well laid out or built, and he recommended rebuilding the post and erecting buildings "with some regard to the welfare of those who are destined to occupy them, and not on the principal of shortsighted and extravagant economy." [44]

While the Surgeon General was concerned with living conditions for the inhabitants, the Adjutant General's office saw things differently. The Brigadier General's office in Santa Fe did not like having to lease the grounds of Fort Union at "an extravagant rate" based on the court decision that the land still belonged to owners of the original land grant; the army risked losing the property if it did not comply with the court decision. So, the district office in Santa Fe recommended transferring some stores to Albuquerque. General Garland did not see much sense in repairing and rebuilding structures on land the army did not own or might lose. [45]

The buildings continued to deteriorate as the years passed. They were, after all, not constructed as permanent buildings. When Bvt. Major William Grier took over the command of Fort Union in June, 1856, he commented on an inspection report that had just been completed. He noted that even making repairs to the quarters would make them "barely tenable, but not really comfortable or very safe for another year." [46] An inspection report to the quartermaster general in Washington at the same time noted that Fort Union was built in a very economical style. The bark was left on the green pine logs, and "the logs laid on the ground without any thing under them to protect them from the moisture &c of the earth.— Some of the buildings are constructed by placing the logs upright with one end in the ground like picket work. The logs are rapidly decaying, and the post will have to be repaired or abandoned." Captain Easton, the author of the report, also noted that he had brought this matter of fort decay to the attention of the Quartermaster General two years earlier. [47]

Shortly after Captain Easton submitted his report to the Quartermaster General in Washington, Captain John McFerran submitted an inspection report to Captain Easton. McFerran stated in no uncertain terms that the entire post needed to be rebuilt before the rainy season started. He commented: "At present some of the company quarters have to be propped up outside & in, to prevent them falling and all of the quarters & public buildings at the post are very much decayed, out of repair, unsafe & filled with insects & vermin." [48]

Living conditions at the fort were still in bad shape in 1859, when post commander Captain Robert M. Morris wrote to the acting assistant adjutant general of the Department of New Mexico. Morris wrote that the company quarters for two companies of rifles were not habitable for winter, and also that Fort Union did not have sufficient space for the companies. Morris requested the employment of "citizen mechanics" to build more space. [49] In response, Morris was denied his request and told to suspend all improvements until instructions came from Washington. [50] Those orders arrived, but in the meantime, Captain Morris was still required to take immediate action. He moved Company G of the Mounted Riflemen out of their quarters because they were in a dangerous, deteriorated condition; then he ordered those quarters to be partially demolished. He temporarily moved that company into the quarters of Companies K and H, which were away from the fort at the time. He requested that the quartermaster at that post reconstruct the buildings quickly, otherwise Company G would be forced to winter in tents, which he felt was impractical, or be shipped elsewhere for winter quarters. [51]

Although no response to that letter appeared in the files, the situation remained grim even two years later. An inspection noted that the buildings:

with scarcely a single exception [are] rotting down, the majority of them almost unfit for occupation and in fact, all of them in such a dilapidated state as to require continual and extensive repairs to keep them in an habitable condition. The Hospital, Commissary and Quarter Master's Buildings are entirely unfit for the purposes for which they are required. There have been no additions to nor alterations of consequence at the Post during the Past Year. Several complained of troops now here are occupying tents because of the lack of quarters for their accommodation. In previous letters from this Office, Plans and estimates have been submitted, to which I beg to refer you. [52]

In January, 1861, the buildings of the fort continued to decay, and the dilapidated condition of the quarters took a particularly strong toll on their occupants. One soldier wrote that the men were "compelled to keep fires all night in Officers (sic) Quarters, and in the Soldiers', they have to leave their bunks, and collect around the fire, so cold are the nights." [53]

Work was still underway to expand the existing storehouses at the first fort in 1861 when construction began on the earthen fortification—the second Fort Union. When it became evident that the entire garrison was necessary to defend the post, work on the storehouses "laid out as joining the old ones was suspended." [54] During the summer of 1861, an order came through that pickets would be stationed near the spring to prevent any individuals from washing or bathing in the spring or the irrigating pond adjacent to it, and to protect the public gardens. Also, the orders called for the construction of a sink for use of the volunteers. The sink was to be screened by brush. [55]

New Construction Ordered. In 1862, General Edward R. S. Canby ordered the Quartermaster Depot and Post to be reconstructed on grounds "contiguous to the Old Post." Major James Lowrey Donaldson, the post commander at Fort Union at the time, did not want to make any recommendations to spend money on the old buildings at the first fort other than what would be necessary to make the structures habitable. In fact, Donaldson admitted that he had $13,000 that he had been authorized to spend on the buildings of the first fort, but he had chosen not to spend the money because he considered that spending it on the old buildings of the first fort would be equivalent to throwing the money away. Thus, he left the money in the Treasury. [56]

Even in 1863, when most of the troops occupied the earthen fortification, at least two officers remained living at the first fort—Majors George W. (?) Burns and Archibald H. Gillespie—because living space was limited in the post. [57] An 1862 inspection noted that: "The old Post, built in 1851, is in a state of dilapidation, having been reported some years ago unfit for occupancy; there are a few buildings which have been repaired and are now used temporarily as quarters and storehouses; it is impossible to render this place fit for permanent use without rebuilding it." [58] Finally in February, 1863, the order came through to "tear down the old house on the hill, known as Col. Sumner's house, which was formerly used as a Hospital at Fort Union—and as far as possible use the lumber and doors and windows now in it to make a set of officers quarters, say four rooms and a Kitchen, with a yard &c., complete and comfortable-over near the Redoubt." [59]

Because the troops needed the space, a group of the Fort Union buildings remained in use through April, 1863. At that time an order issued out of department headquarters in Santa Fe ordered the commanding officer of the post of Fort Union to move into the new quarters (probably HS-224) near the earthwork. Also, all enlisted men and laundresses belonging to the garrison were to move into the demi-lunes or into tents for shelter, pitched near the redoubt. At that time, the depot quartermaster was to take possession of all of the buildings of old Fort Union (with the exception of the ordnance depot buildings, presumably because they were a separate command) for the use of the quartermaster and subsistence depots and for quarters for general staff officers. [60]

Although most reports discussed the dilapidation of the buildings at the first fort, one observer presented a more lyrical view. Mrs. Eveline Alexander visited Fort Union in 1866 and described the buildings at the old fort as "one story houses . . . [with] a flat roof made of logs filled in with mud and this affords but a poor protection against the rain." She also wrote that she visited the old Fort to return the calls she had received from the Shoemaker family. While she was there, she noted that some of the old houses "had quite a flower garden on their roofs which had sprung up from the mud. Most of the old houses here have been torn down." [61]

Structures on the edge of the first fort also became worn out from bad construction and overuse. During the summer of 1866, authorization came through to construct a new butcher corral. The first one had "the accumulated blood of the winter, as well as the bones of years" that made it offensive. [62] In November, 1866, the officers' quarters in the third fort were not yet completed, so the officers were living "in the unoccupied quarters of the Depot's old Garrison." [63] Other than the arsenal buildings, this was the last time the army officially used any of the old buildings at the first fort.

Summary. When the army moved into the area around Los Pozos during the summer of 1851, the first order of business was construction of buildings to house the troops and supplies. Temporarily the soldiers, their families, civilian staff, and supplies were housed in tents on the prairie. During that time, the troops cut ponderosa pine timber—the primary building material. They also manufactured other building materials including lime, cut stone, and adobes. After the sawmill arrived at the fort, boards were available to cover roofs and to serve as floor material.

The buildings, however, were erected in such haste that most were not constructed with foundations under them. Because the unpeeled logs lay directly on the ground, rot set in quickly. The installation of gable roofs made of sawn boards on top of the flat earthen roofs slowed deterioration from above. Because the buildings were so shoddily constructed, deterioration began within the first two years of construction. Constant patching and refitting held the buildings together for use through 1861; but then work began on the second fort and in 1863 work began on the third Fort Union.

While these were under construction, salvaging building materials from the first fort was common practice because those items were so scarce on the frontier. As the materials—boards, windows, glass, and stone—were salvaged, additional deterioration set in to the first fort buildings. Although the remaining buildings did receive some intermittent use through the fall of 1866, the army set aside a separate reservation for the arsenal that same year. The arsenal reservation included nearly all of the area of the first Fort Union.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

foun/hsr/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006