|

Fort Vancouver

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

I. MANAGEMENT SUMMARY

PROJECT BACKGROUND

Fort Vancouver National Monument was established in 1948 to protect and maintain "the site of the original Hudson's Bay stockade and sufficient surrounding land to preserve the historical features of the area...", and preserve "the historic parade ground of the later U.S. Army post." The purpose of preserving the site was to interpret its role as a primary center of economic, social, cultural, and military development in the Pacific Northwest, and the part it played in our nation's westward expansion. [1] To fulfill these interpretive objectives, the National Park Service (NPS) initiated archeological investigations in the late 1940s and early 1950s to relocate and outline the fort stockade and major buildings inside the stockade. In 1961, the park's importance was further recognized through a Congressional Act that authorized enlarging the park and redesignating the monument as a historic site.

Following this expansion, the park embarked on a plan to go beyond interpreting the site as an on-going archeological excavation and begin to interpret the site through accurate historical reconstructions. In 1966, the north wall and a portion of the east wall were reconstructed. Beginning in 1972, and continuing to the present, another period of reconstruction ensued that led to the completion of the stockade, eight key buildings inside the stockade, and some small-scale features. In addition to these reconstructions, the historic scene was enhanced by reestablishing landscape features such as the historic north gate road, an interpretive orchard and garden, and post and rail fences.

These stockade reconstructions have done much to advance the interpretation of the site as a major Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) fur-trading center, but have been limited in terms of interpreting the fort's vast agricultural and industrial operations. The 1978 Master Plan recognized the need to expand the historic scene through general proposals that included restoring the cultivated fields, garden, and orchard; restoring East Fifth Street to its historic appearance; continuing land acquisition of key historic property; and providing interpretive facilities at the Columbia River waterfront area. While reconstructions of buildings within the stockade proceeded, few of the Master Plan's other proposals were implemented.

In recent years, the need for an updated Master Plan has arisen due to changes in park policy, contemporary program needs, and through on-going research which has led to a better understanding of the fort's history. This project will serve as a technical document that will supplement the Master Plan development process. The intent of this project is to identify and evaluate all significant cultural landscape resources and provide management recommendations for the preservation and enhancement of the historic scene at Fort Vancouver ca. 1844/46. The study investigates and documents a range of treatments for reestablishing key landscape components and features that contribute to interpreting a full spectrum of HBC operations and activities.

The scope of work for this report did not include any preliminary findings associated with the congressionally mandated study addressing the possible establishment of Vancouver National Historical Reserve. The purpose of the Commission study is to examine the historic, cultural, natural, and recreational significance of resources in the Vancouver, Washington area, and to determine the feasibility of a historical reserve. [2] Historic resources considered in the study include Fort Vancouver N.H.S., Vancouver Barracks, Pearson Airpark, and the W.W.I. Kaiser Shipyards. The Vancouver Historical Study Commission was in progress when the cultural landscape report was completed. Because it was impossible to surmise when or if Congress would approve of the historical reserve and what form the reserve would take, this report does not address the idea of a Historical Reserve, but concentrates on preservation treatment for Fort Vancouver's HBC cultural landscape resources. If at a future date, the Vancouver National Historical Reserve becomes a reality, recommendations and/or concepts of the cultural landscape plan described in this report may require additional review and/or revision.

One outcome of not including the Vancouver Historical Study Commission issues concerns NPS property in the eastern portion of the Fort Vancouver N.H.S. that is currently part of the municipal airport, Pearson Airpark. The Cultural Landscape Report utilizes the existing legal agreement concerning Pearson Airpark. The Statutory Warranty Deed, signed April 4, 1972, authorized the NPS to purchase 72.57 acres from the city of Vancouver to the NPS, with a "reservation" clause allowing the City to use the property for thirty years (until 2002). The final design recommendations and cultural landscape plan for the Cultural Landscape Report are based on NPS resources after the year 2002, when the City has vacated the Pearson Airpark property. Again, if the Historical Reserve is recommended and approved by Congress, this plan will have to be revised to accommodate any Congressionally recognized Pearson Airpark historic resources.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT [3]

Fort Vancouver National Historic Site has a rich and varied history, from its beginning as the most important Hudson's Bay Company post in the Pacific Northwest, through its development as the primary U.S. Military post in the region, to the present, as an important archeological and interpretive unit in the National Park Service. The site's development as chronicled in the landscape history identifies six periods of landscape development including: Fort Vancouver: Establishment 1824-1828; Fort Vancouver: Principal Development 1829-1846; Fort Vancouver: Transition 1847-1860; Fort Vancouver: Vancouver Barracks 1861-1918; Fort Vancouver: Vancouver Barracks 1919-1947; and Fort Vancouver: National Park Service 1948-Present. The focus of the Cultural Landscape Report is on the Hudson's Bay Company occupation from 1824-1860.

In 1824, George Simpson, the governor of the Hudson's Bay Company's Northern Department, ordered the establishment of a new fur-trading post on the north side of the Columbia River. This post was named Fort Vancouver. During its existence between 1824 and 1860, Fort Vancouver became the most important settlement west of the Rocky Mountains. As administrative headquarters and principal supply depot for the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia District, Fort Vancouver developed into the economic, political, social, and agricultural center of present day Washington, Oregon, western Montana, and Idaho states, and British Columbia, Canada.

The fur resources of the Pacific Northwest began sparking the interest of American and British traders in the late 1780s when British explorers reported rich supplies of fur pelts. Soon, fur traders from North America and Europe began competing for these valuable resources. The 1804-1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition across the continent to the mouth of the Columbia River, increased interest in fur-trading profits in the Columbia River area. Beginning in 1811, John Jacob Astor from New York organized the Pacific Fur Company and established several fur-trading posts in the Columbia Basin, including Fort Astoria, on the south side of the mouth of the Columbia River. In the meantime, the powerful British fur-trading company from Montreal, the North West Company, had established posts in present day British Columbia and had expanded into the Columbia basin. The two companies competed with each other until the war of 1812, between America and Great Britain, disrupted supplies for the Pacific Fur Company. In 1813, the Pacific Fur Company was forced to sell out to the North West Company. The Canadian company took control of Fort Astoria, renaming it Fort George. The North West Company controlled the fur-trading industry in the Pacific Northwest until 1821 when it merged with its principal rival, the British Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). The reorganized Hudson's Bay Company divided North America into two departments, the Northern Department, which included the Columbia District and New Caledonia District, and the Southern Department. In 1824, the Hudson's Bay Company decided to move the headquarters of the Columbia District from Fort George to a more strategic location one hundred miles upstream to the north side of the Columbia River.

The decision to move the headquarters was primarily based on the desire to strengthen British claims to the land north of the Columbia River, and to find land suitable for large-scale subsistence farming. Starting with the Treaty of Ghent, after the war of 1812, the United States and Great Britain tried unsuccessfully to resolve boundary issues concerning the territory west of the Rocky Mountains, from Spanish settlements in the south, to Russian posts in the north. In 1818, a joint occupation treaty was negotiated that left this territory open to both countries for a period of ten years. In 1824, boundary negotiations were suspended leaving the HBC in a position to exploit the trade potential of the area between the forty-ninth parallel and the lower Columbia River. Establishing a fur-trading post on the north shore of the Columbia River supported the British campaign for dominion over the region.

|

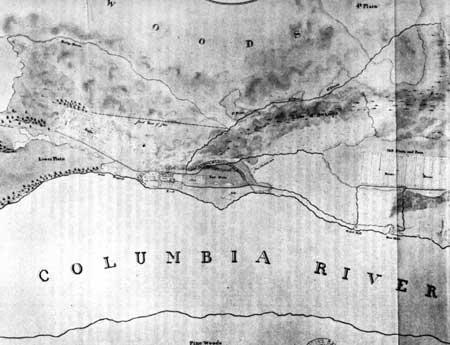

| "Sketch of the Environs of Fort Vancouver..." by H.N. Peers, (post 1844) showing Lower Plain, Fort Plain, Mill Plain and the Back Plains. Credit: Hudson's Bay Company Archives Provincial Archives of Manitoba. |

In the winter of 1824-1825, Fort Vancouver was constructed on a bluff sixty feet above a low-lying river plain. In addition to its strategic political location, the site was chosen for its agricultural potential. During the next four years, 1824-1828, the foundations were laid for international trade and a vast agricultural enterprise. In 1829, Fort Vancouver became the chief administrative headquarters of the Columbia Department. The decision to make the fort the principal Hudson's Bay Company establishment in the Pacific Northwest, and the stockade's inconvenient distance from the Columbia River, precipitated rebuilding the stockade at a new site lower down on the river plain, about one mile southwest of the first stockade site. It is the site of the second fort that is preserved at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

The principal period of development for Fort Vancouver was between 1829 and 1846. During this time, Fort Vancouver's influence in the Pacific Northwest reached its peak and the site was developed to its fullest extent. Under the leadership of Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin, Fort Vancouver dominated the fur-trade industry and became the administrative and producing hub of an important agricultural and manufacturing establishment. The agricultural operations at the fort extended for miles along the north shore of the Columbia River, with farming operations located on several large plains surrounded by extensive forests. Agricultural features included cultivated fields, livestock pastures, dairies, and piggeries, as well as the fort's garden and orchard. Agricultural operations also extended beyond Fort Vancouver to outlying areas such as Cowlitz Farm and Fort Nisqually, as part of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company, a subsidiary of the Hudson's Bay Company. In addition, Fort Vancouver's influence and control spread south into the fertile Willamette Valley, to a large island in the Columbia River now known as Sauvie Island, and to other areas of the region.

Manufacturing operations also contributed to the fort's prominent lead in Pacific Coast trade, including trade with California, Hawaii and Alaska. Industrial operations included large-scale timber milling, grain milling, and salmon fishing. Industrial activities that supported the fort's operations included coopering (barrel making), boat building, hide tanning, and blacksmithing.

Fort Vancouver was also the social and cultural center of the region. The first schools and churches were established at the fort, and social activities enjoyed by employees, visitors, and settlers included plays, balls, dinners, and picnics. Also, as the only source of emergency shelter and transportation, and the only dependable supply of food and clothing, Fort Vancouver became a destination point for American missionaries during the 1830s, and American settlers in the 1840s. Although Hudson's Bay Company policy did not encourage American settlers in the region, Dr. McLoughlin, through necessity and kindness, helped most settlers by supplying them with material necessary to start a farm including seed, livestock and agricultural implements.

The HBC policy on and treatment of Native Americans in the region was directed to maintaining a peaceful coexistence. The predominant group of Native Americans in the region were speakers of several closely related Chinookan languages. They occupied an area that was concentrated along the bank of the Columbia River from the mouth of the river at Astoria, to the Dalles east of the Cascade mountains. Those Chinookan speakers who had villages near Fort Vancouver spoke the Multnomah dialect of Upper Chinookan. [4] Their economy was based primarily on fishing, hunting and gathering. Although the HBC defended its property and employees, and exacted retribution for damage, Chief Factor McLoughlin noted that as traders, it was in the best interest of the Company and more profitable to treat the Indians fairly and avoid hostilities. [5] The local Multnomah Chinookans and other Indians interacted in Fort Vancouver's social and economic network through trading, as HBC "engage" or "servant" class employees, and through liaisons or marriages between Indian women and non-Indian HBC male employees. The most dramatic and far-reaching consequence of contact period history for Chinookans in the region was severe population decline due to smallpox, measles, malaria, and other diseases. In the early 1830s, an estimated ninety-eight percent of the Chinook population in the Portland Basin, including both Multnomah Chinookans and the more easterly Clackamas Chinookans died. The entire population of a Multnomah Chinook village in the vicinity of Fort Vancouver was exterminated by disease during this epidemic. [6] In the 1850s, the few Multnomah that survived diseases moved onto reservations (located away from the Columbia River) in exchange for residual fishing rights. [7]

In the early 1840s, as the American population in the region grew and the boundary dispute between Great Britain and the United States escalated, the Hudson's Bay Company began to transfer some of its operations from Fort Vancouver to Fort Victoria, in present day British Columbia. This administrative shift was accelerated by two events in 1846; the Treaty of 1846 which established the boundary at the forty-ninth parallel, and the termination of McLoughlin's superintendency of Fort Vancouver. During the following decade, the fort's influence declined as it was reduced to a subordinate trading and supply post, and Fort Victoria became the principle HBC center. In 1849, the U.S. Army established a military post on the hill above the fort's stockade. Although the HBC and the army co-existed somewhat peacefully for several years, political, economic and social pressure by increasing numbers of Americans led to losses of thousands of acres of HBC land to American squatters and increasing hostility towards the HBC. In 1860, Fort Vancouver was abandoned and the remaining HBC land around the stockade was encompassed by the 640 acre military reservation, claimed by the U.S. Army in 1850.

In 1848, the U.S. Secretary of War ordered the establishment of a ten square mile military reservation on the Columbia River, part of a series of military posts authorized to protect settlers traveling from the Mississippi to the Columbia. In May of 1849, a column of riflemen and two artillery companies arrived at the HBC's Fort Vancouver where they established a camp, called Camp Vancouver, on the hill above the stockade. By 1850, more soldiers had arrived, twenty-six buildings had been constructed, and the army had formally proclaimed the establishment of a military reservation called Columbia Barracks. In 1865, the army's Department of Columbia was established with Columbia Barracks as its headquarters until 1867 when it moved to Portland. The Columbia Department included Oregon, Washington and Idaho territories. In 1878, the headquarters for the Columbia Department was returned to Columbia Barracks and a period of expansion ensued. The post was renamed Vancouver Barracks in 1879, a name that continues to the present.

From its establishment in 1849 until World War I, Vancouver Barracks was the principal military site in the Pacific Northwest. Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, the soldiers of Columbia Barracks primarily engaged in enforcing domestic policies in the Pacific Northwest including actions to control periodic Indian uprisings with the Nez Perce, Modoc and Bannock Indians. The post also served as headquarters for organizing survey and exploration expeditions to Alaska in 1870s and 1880s. In the late 1880s and 1890s, forces at Vancouver Barracks served as a police force during civil unrest in the region including anti-Chinese riots in Seattle and Tacoma, Washington, mine union strikes in Coeur d' Alene, Idaho, and railroad union strikes that occurred across twenty-seven states and territories. During World War I, the Spruce Production Division, part of the U.S. Army Signal Cops, was formed at Vancouver Barracks to provide milled spruce for Allied demands. It became the site of the Cut-up Plant, the largest spruce mill in the Division. While the post served an important role in the war, with the construction of Camp Lewis which became a major training and assembly point for overseas bound soldiers, Vancouver Barracks was no longer the most important military site in the region.

Between World War I and World War II, military activity at Vancouver Barracks was low. During this time the post served as a Citizen's Military Training Center, and a branch of the newly formed U.S. Army Air Service began operations at Vancouver Barracks which led to the establishment of an army airfield in 1925. The post also served as a headquarters and dispersing agency for the Civilian Conservation Corps program in the Pacific Northwest during the 1930s. During World War II, Vancouver Barracks was revitalized when it served as a staging area for the Portland Subport of Embarkation under the control of the Ninth Service Command. It also served as a training center for some units. In 1946, Vancouver Barracks was declared surplus by the army. The reservation was slated for disposal but in 1947 about sixty-four acres of the post were reactivated to serve as headquarters for reserve training in the Pacific Northwest. Today, Vancouver Barracks occupies fifty-two acres of the original reservation and is under the command of Fort Lewis, Washington. A portion of Vancouver Barracks lies within the authorized boundary of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

|

| 1859 map by Richard Covington showing the overall organization of Fort Plain. Fort Vancouver N.H.S. photo file. |

METHODOLOGY AND SCOPE

The Cultural Landscape Report for Fort Vancouver consists of two main parts: 1) research, analysis and evaluation, and 2) design development. A wide range of primary and secondary sources were reviewed for the research portion of the report. The park's extensive historical files and archives were reviewed including historic photos, maps, illustrations, journals, diaries, and the records associated with numerous archeological investigations. In addition, a large body of existing historical material was also reevaluated including periodicals, special studies, U.S. Army records, and primary research books such as John Hussey's The History of Fort Vancouver and its Physical Structure (1957) and Fort Vancouver Farm (n.d.). In addition to the National Park Service files, historical research was conducted at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.; the Hudson's Bay Company Archives in Winnipeg, Canada; the Royal Provincial Archives in Victoria, British Columbia; the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; and the archives of several key historical societies in the Pacific Northwest. The extensive collection of archeological records, reports, and maps also played a key role in the research phase of the study. This included two new archeological projects that were completed for this report. The first project involved development of a comprehensive archeological base map for Fort Vancouver and Vancouver Barracks, based on a reconciliation of all existing archeological excavation maps. The second project utilized remote sensing, a non-invasive archeological technology, to investigate the conjectural location of several historic structures and features. Both of these projects were critical for accurately mapping confirmed and conjectural locations of non-extant historic structures and features. Based on this research, a detailed landscape history and historic base maps were prepared for six historic periods of landscape development. The landscape history and base maps are found in Volume II of this report.

In addition to historical research, all park resource and planning documents were reviewed and an inventory of existing conditions was conducted. Documentation of existing conditions included the preparation of an accurate 1:200 scale site map that was used as the primary base map for the project. In the analysis portion of the project, an evaluation of the historical research and existing conditions led to identification of key character-defining features, significant historic resources, and contemporary site impacts. This evaluation set the framework for design development.

Based on the analysis and evaluation, seven cultural landscape character areas, and five management zones were identified providing a framework for the development of a landscape design. A series of design recommendations and alternatives were developed according to the general management philosophy of the park which is to preserve, restore, and reconstruct (when appropriate) key landscape patterns and features that are critical to the park's interpretive mandate. These design alternatives were reviewed by park and regional staff. Based on this review, a preferred alternative combining elements from several plans was selected and refined. Finally, a three phase plan was developed to facilitate both short and long-term implementation of the plan.

The scope of this report was influenced by several factors. In addition to issues associated with the Vancouver Historical Commission Study and Pearson airpark, a significant portion of the cultural landscape historically associated with Fort Vancouver is outside of current park boundaries. In keeping with NPS management policy, design recommendations have been developed only for property in which the NPS has current legal interest. The portions of Vancouver Barracks within the authorized park boundaries but owned by the U.S. Army will be addressed in the research section but, with few exceptions will not be addressed in the design recommendations. Prior to any action impacting these resources, however, an evaluation of their significance and integrity should be completed.

The focus of the Cultural Landscape Report is based on the park's primary mandate, to interpret the role of the Hudson's Bay Company in the development of the Pacific Northwest. Although the historical research covers the landscape development at Fort Vancouver up to the present--including an extensive discussion of Vancouver Barracks--the primary focus of the analysis and evaluation, and design development is on the cultural landscape of the HBC occupation, specifically the principal development period, 1829-1844/46.

This report concentrates on the physical development of the fort rather than social development, therefore, the impact of the Hudson's Bay Company on Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest and at Fort Vancouver is not detailed. Additional research should be conducted for inclusion in the interpretive program.

ADMINISTRATIVE CONTEXT FOR THE

PROJECT

As part of the planning process, all approved park documents and policies were reviewed and included, as appropriate, in the report's recommendations. The administrative basis of this project stems from the park's enabling legislation as well as several park planning and management documents. These documents included the Master Plan (1969 & 1978), Statement for Management (1976, 83-85), Interpretive Prospectus (1985), and the Resource Management Plan and Environmental Assessment (1986).

The following management objectives for the historic landscape were approved in the 1978 Master Plan and Statement for Management (1976, 83-85):

1) "Secure a land base through acquisition or other means that facilitates preservation of the historic scene and interpretation of the cultural resources within the historic site's authorized boundary;

2) Include a greenbelt plan for the Columbia River waterfront as an integral part of the Fort Vancouver site and strive for a physical access connection with the main fort site unit;

3) Restore the fort scene on its original location to its historic appearance insofar as is possible by planting fields, pastures, and the orchard and by reconstructing fences and roads;

4) Reconstruct . . . additional buildings outside the stockade as is necessary to enable visitors to visualize the historic fort's full range of structures and activities;

5) Ensure that visitor-use facilities and developments are compatible with the historic scene and maintained in a manner consistent with the purpose for which this historic site was established; and

6) Interpret, as the primary theme, the story of the fur trade and the important role played by the Hudson's Bay Company in the exploration, settlement, and development of the Pacific Northwest. As a second theme, interpret the story of Vancouver Barracks and the part played by the United States Army in opening the Northwest to American settlement." [8]

ENDNOTES

1. National Park Service, Fort Vancouver N.H.S. Master Plan, February, 1978.

2. Memorandum, Stephanie Toothman, Chief, Cultural Resources Division, Pacific Northwest Region, to Director, Pacific Northwest Region, October 29, 1990, Planning Division ???? Files, Pearson Correspondence 1990, PNRO.

3. A complete landscape history can be found in Volume II of this report. Cultural Landscape Report: Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Volume II.

4. Silverstein, Micheal, "Chinookans of the Lower Columbia" in Handbook of North American Indians, William C. Sturtevant general editor, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., 1990, Volume 7: Northwest Coast, pp. 533-535.

5. Carley, Caroline D., HBC Kanaka Village/Vancouver Barracks 1977, Office of Public Archeology, Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Washington, Seattle, WA. p.3, 1982.

6. Thomas, Bryn, An Archeological Overview of Fort Vancouver, Vancouver Barracks, House of Providence, and World War II Shipyard, Clark County, Washington, Archeological and Historical Services Eastern Washington University, submitted to: National Park Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Cultural Resource Division, CA 9000-8-0008, pp. 1-2, March 1992.

7. Silverstein, "Chinookans of the Lower Columbia", p. 535.

8. National Park Service, Resource Management Plan and Environmental Assessment, 1986, pg. 1-2.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

fova/clr/chap1-1.htm

Last Updated: 27-Oct-2003