|

Fort Vancouver

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

II. FORT VANCOUVER: TRANSITION, 1829-1846

1829-1846

The period between 1829 and 1846 encompasses the principal period of development of Fort Vancouver under the Hudson's Bay Company. During this time, which begins with a major site development--the move of the fort proper from its original site to the location of the present reconstruction--Fort Vancouver's economic, political and social influence in the region reached its peak. The boundaries of the site were at their greatest extent. The Fort's administrative importance, as vested in Chief Factor John McLoughlin, was supreme in the Pacific Northwest While fur-trading activities declined throughout this period, agricultural activity under the Hudson's Bay Company flourished, with Fort Vancouver as the administrative and producing hub. In addition, many early industrial activities were initiated and developed at the fort--including large-scale timber milling, salmon fisheries, grain milling--which led to its prominence in Pacific Coast trade, with trading connections in Hawaii, California, and Alaska. The fort was the social center for the region throughout most of the period, with balls, plays, picnics and dinners attracting settlers from many miles away. During the latter years of this period, the Company's stores at the fort and cattle, seed, and produce from its fields, provided the first waves of American settlers in the region with the means to establish their farms--in some cases with the means to survive their first winter; these operations had a significant influence on the settlement of the region, from Puget Sound in Washington to the Willamette Valley in Oregon, and east as far as the Dalles, Oregon. Against a backdrop of the influx of American settlers, with attendant political and economic agendas and under a threatened imminent settlement of the northwest boundary dispute between Great Britain and the United States, the period ended with two events of particular significance: first, the signing of the Oregon Treaty of 1846, finally resolving the boundary issue; second, London's decision to terminate McLoughlin's superintendency of Fort Vancouver.

Administrative and Political Context

During this period Fort Vancouver served as the administrative center for the company's posts west of the Rocky Mountains. While American fur traders periodically mounted expeditions into the west, the Hudson's Bay Company, with its increasing number of trading posts--both on the coast and inland--and with established methods and routes for trade goods, fur processing and export, and a sufficient means of provisioning its posts and employees, dominated the trade in peltries until the rich fur resources of the region finally began to give out. Simpson's policy of increasing the supply of "in-country" produce, reducing the reliance on imported provisions, spurred the development of agriculture and other industries under Company aegis, which ultimately led, in the late 1830s, to the establishment of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company (P.S.A.C.), a subsidiary of the Hudson's Bay Company. This, in turn, made the Company the major player in Pacific Coast trade.

Early American missionaries in the Pacific Northwest ended their arduous overland treks and ocean voyages at Fort Vancouver, the principal settlement in the region in the 1830s, where they received necessary supplies, livestock and equipment to begin their own establishments. They were instrumental in publicizing the attractions of the rich Willamette Valley to land-hungry Americans in the States; in the late 1830s, the first wave of settlers reached the Oregon Country. Up until 1842-43, Fort Vancouver served as the principal supplier of food, clothing and materials to start a farm; the Company expanded its merchandizing and milling operations, opening stores in San Francisco, Oregon City and the Willamette Valley, and mills in Oregon City and Champoeg.

The principal political backdrop during this period was the uncertainty regarding the final location of the boundary between British and American territory in the Pacific Northwest In August of 1827 the joint occupation agreement regarding the disputed land was indefinitely extended, leading the Hudson's Bay Company to augment operations at Fort Vancouver's strategic Columbia River location, and for some years it was generally believed the boundary would be established along the lower Columbia River, leaving Fort Vancouver in British territory. By the 1840s, with the influx of American settlers into the Oregon Country, British assumptions regarding the boundary became increasingly unrealistic. In 1846 the Oregon Treaty was signed, establishing the boundary at the 49th parallel, legally ending British dominion over lands the Company had developed and exploited for over twenty years.

Seat of Columbia Department

Fort Vancouver became the supply center and administrative locus for an expanding number of fur-trading posts and two agricultural outposts. Returns from the Columbia Department and New Caledonia fur brigades were shipped via canoe and bateaux to Fort Vancouver, where they were inspected, prepared for shipment and recorded, and then loaded on the annual supply ships sent from London. From Fort Vancouver, annual supplies and trade goods for each post were ordered from London, and repacked, invoiced and shipped out to the posts. Under McLoughlin's direction, fur brigades were sent from the various posts to trap out the areas south and east of the Columbia River region, creating a "fur desert," which, combined with control of the Indians and various sales and bidding strategies for furs, was largely successful in ruining American competitors in the region. 103 By the early 1830s the rich fur resources of the Snake River region had been decimated by the Company, and by the early '40s, fur brigades to California, which had been conducted annually since 1835, ceased to be profitable.

A number of new posts were established during this period, including Fort Boise, in what is now Idaho, Fort Simpson, on the Nass River in Alaska (1831); Fort McLoughlin on Millbanke Sound (1833), and Fort Nisqually and Cowlitz Farm, the latter two principally as agricultural centers. At the end of this period, the Columbia Department posts administered from Fort Vancouver included the aforementioned forts, as well as Fort George, Fort The Dalles, Fort Nez Perces, Fort Okanogan, Fort Colvile, Fort Flathead, Fort Kootenai, Fort Langley, Fort Rupert, Fort Umpqua, and Fort Victoria.

Over time each post within the Department came to rely more on produce raised "in country," including cattle, grain, and so forth, either from its own location, or from other posts, particularly Fort Vancouver, and later Cowlitz Farm and Fort Nisqually, a result of the policy formulated by Simpson and London to reduce the expense of transporting foodstuffs from London. McLoughlin's letters to chief factors and chief traders at various posts during this period often include specific instructions for agricultural production, for intra-post shipment of produce, seed and livestock, and for repairs of tools, structures and expensive manufactured items.

As the years progressed, Fort Vancouver, under John McLoughlin's administration, and following policies established by Governor George Simpson and the Company's London directors, became the principal manufacturing and agricultural center in the Pacific Northwest. Eventually, products from cattle, swine and sheep were used not only to sustain the Company's posts, but to barter and sell to immigrants and to export markets. Commodities harvested and produced at posts other than Fort Vancouver, such as salmon from Fort Langley, were part of the Columbia Department's production; the operations were overseen by McLoughlin at Fort Vancouver. Agricultural operations--tares, clover and other crops to sustain livestock, and a significant amount of wheat for milling and marketing to local consumers and for export--continued to expand throughout this period, overseen by the offices at Fort Vancouver. In addition, the Company's Pacific Coast trade--the operation of ships servicing Company posts and carrying exported and imported goods--was directed from Fort Vancouver.

As the Company's principal administrative representative in the region and head of the Columbia Department, Chief Factor John McLoughlin directed every aspect of Company operations, from relations with Indians and American immigrants, to quantities and methods of agricultural production at the various posts. Because Fort Vancouver was the Company's principal west coast center for import and export, Fort Vancouver clerks kept accounts and records of all orders and shipments in furs, produce and manufactured items received from, or sent, abroad or sold in-country in the Columbia Department. The scope and power lodged in McLoughlin, as the Columbia Department's Chief Factor during this period, is illustrated by arrangements made for administration while McLoughlin was on leave in 1838. While he was absent the posts on the upper Columbia were administered by one chief factor, Samuel Black; the maritime trade and expeditions and posts on the lower Columbia, including Fort Vancouver, were placed under the control of Chief Trader James Douglas; and the administration of New Caledonia, an area where McLoughlin apparently spent little administrative energies, was directed by Chief Factor Peter Skene Ogden, who already operated it on a mostly autonomous basis. When McLoughlin returned from his furlough in the fall of 1839, he resumed direction of these various operations, with the additional charge of heading the administration of the newly-established Puget's Sound Agricultural Company.

Fort Vancouver, as the Columbia Department depot, also administered a relatively short-lived merchandising venture in San Francisco (1841-45), and a trading establishment in the Hawaiian Islands (1833-1844). [104]

During the first few years of the 1840s, London began to express concern over some of McLoughlin's actions in the Columbia Department, including unauthorized expenditures at Oregon City and the credit advances he had been giving settlers. The Governor and Committee were also dissatisfied with the decline in revenues in the Department, and the failure of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company to bring in projected profits. In 1841 George Simpson returned to the Columbia for the first time since 1828-29. He and Chief Factor McLoughlin disagreed on the operations of the coastal trade, and their increasingly bitter discussions ended in a quarrel. Then, in 1842, Simpson found upon revisiting Fort Stikine, where John McLoughlin, Jr., was in charge, that the Chief Factor's son had been murdered by his own men. Simpson's handling of the affair was unacceptable to McLoughlin, who then conducted his own inquiry into the matter, arrested the men involved in his son's death, and insisted they be tried for murder. His letters to the Governor and Committee over the next four years were full of references to his progress in his murder investigation, and of accusations against Simpson's handling of the affair, including lodging responsibility for the murder with Simpson, who he claimed had left his son in charge of Stikine without adequate help. London directed McLoughlin to resolve his differences with Simpson, but McLoughlin ignored the direction. In 1844 McLoughlin was removed as sole administrative head of the Columbia Department; a joint administrative board for the department was established, to take effect in 1844-45, with McLoughlin sharing administrative tasks with Chief Factors James Douglas and Peter Skene Ogden. Using McLoughlin's purchase of land in Oregon City--which he made, ostensibly, in the name of the Company to protect its interests under the Oregon territorial donation land claim law--as a wedge, Simpson was able to force McLoughlin into retirement. The Chief Factor left Fort Vancouver in January of 1846.

Boundary Issues

As noted previously, in the summer of 1824, Great Britain and the United States suspended boundary negotiations regarding the territory between the 49th parallel and the lower Columbia River, leaving its ultimate fate unresolved and resulting in the Hudson's Bay Company's determination to exploit the region's fur resources and the development of its west coast operations, particularly Fort Vancouver. However, between 1829 and 1846, immigrants from the United States--spurred by published reports of fertile land from a trickle of early settlers and from American missionaries--began to settle in what became known as the Oregon Country, particularly in the Willamette Valley south of the Columbia River. From a total of sixty-five Americans settled in the Willamette Valley in 1841, by 1843, the number had grown to over one thousand. British attempts to counter American numbers with presumably loyal British subjects--most notably the Hudson's Bay Company attempt to resettle Red River colonists north of the Columbia River in 1839--were not successful. [105]

By the early 1840s it appeared that the boundary between British territory and the United States might well be drawn north of the Columbia River. In the spring of 1842, George Simpson, who, on an 1841 visit to the Columbia, had determined that a site on the south end of Vancouver Island was a more suitable and accessible location for the Company's shipping business--a new main depot to replace Fort Vancouver--directed Chief Factor McLoughlin to begin construction of a new post on that site. Construction of Fort Victoria on the harbor at the south end of the island under the supervision of Chief Factor James Douglas began in 1843. By 1845, a portion of the London cargo once shipped to Fort Vancouver for distribution was being shipped directly to Fort Victoria, and Columbia Department furs were sent directly to the new depot, rather than Fort Vancouver, for shipment to England. [106]

On June 15, 1846, the Oregon Treaty between Great Britain and the United States was concluded, fixing the boundary between British territory and the United States at the 49th parallel. Among the clauses of the treaty were guarantees respecting the "possessory rights" to land and property of the Hudson's Bay Company and the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company south of the border and guarantees of free navigation of the Columbia River for the Company. To determine the value of the lands and property of the Company now in United States territory, already being appropriated by American squatters and clearly unlikely to be retained in the future, Governor Simpson ordered an inventory of all property owned by the Company and its subsidiary, which was performed in late 1846 and early 1847. Using this inventory as a basis, the Company assigned monetary value to all its property, including structures and improvements, and submitted it as a claim to the U.S. government; representatives of the United States independently assessed the value of the Company's holdings. Ultimately, an international commission was established to settle the Company's claims and gather testimony; the process dragged on for over twenty years. [107]

Relationship with Americans

Generally speaking, American immigrants were well received at Fort Vancouver by Chief Factor McLoughlin. Among those who stayed at Fort Vancouver and received assistance were Methodists Rev. Jason Lee and Rev. Daniel Lee, who were to establish the Methodist Mission near Salem, Oregon, an institution which later contributed much to the American settlers' demands for the establishment of the Oregon Territory: it was McLoughlin who sent the Lees to the Willamette Valley--well south of the Columbia River--after their arrival in 1834. The Methodist mission size was enlarged somewhat in 1837, and considerably in 1840 when the Lausanne arrived from the States via Cape Horn. In 1835 the Rev. Samuel Parker, from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, arrived at Fort Vancouver, where he received free board and lodging, and free travel for his investigations of missionary work among the Nez Perces and Flathead Indian tribes. He was followed by Dr. Marcus Whitman and his wife, Narcissa, the Rev. Henry H. Spalding and his wife, and W.H. Gray, all of whom lodged at the fort, received assistance in the form of tools, livestock and seed, and who were aided in establishing their missions near Walla Walla and Lapwai.

Up until 1842-43, Fort Vancouver served as the principal supply for food, clothing, and materials to start a farm for Americans arriving overland: in 1833 John Ball wrote to friends back east, "He [John McLoughlin] has liberally engaged to lend me a plough, an axe, oxen, cow &c." [108] Reports of such aid, printed in newspapers in the states, furthered interest in migration. In the following years, reports from missionaries and other early travelers and settlers who found the Oregon country hospitable and fertile, sparked increasing numbers immigrants. Jason Lee, of the Methodist Mission, began to lecture on the advantages of the Oregon Country when he visited the east coast in the late 1830s, and his speeches and the 1838 published journal of his travels contributed to the spread of Oregon fever. By 1841 there were sixty-five Americans in the Willamette Valley, to whom McLoughlin had loaned seed, livestock and agricultural implements. By 1843 over one thousand American settlers had established themselves in the valley, and the economic base had begun to shift to there from Fort Vancouver. That year settlers in the Valley voted to form a Provisional Government, which McLoughlin felt obliged to join and pay taxes to, to protect the Company's interests. But for most of this period, it was John McLoughlin at Fort Vancouver who aided the Americans: his reasons have often been described as humanitarian--without aid, the settlers would almost certainly have starved--but assistance was also forthcoming to avoid confrontations and probable looting.

By the mid-1840s, squatters were claiming increasing amounts of Company lands. In March of 1845 James Douglas reported to Governor Simpson that Americans were attempting to establish claims at Fort Vancouver in the vicinity of Prairie du The', "above" the sawmill, on Sauvie Island, and west of the fort as far as the Lower Plain, where a Henry Williamson was attempting to lay out building lots near the Company's employee village. "We," Douglas wrote, "are determined to eject him at all hazards, otherwise they will go on with their encroachments until they take possession of our very garden..." Successful appeals to a still sympathetic Oregon Provisional Government, which upheld the Company, managed to forestall some efforts by squatters, and the Company embarked on a largely unsuccessful scheme to counter American claims by having their officers and employees take out claims to various portions of Fort Vancouver lands in their own names. [109]

After news of the settlement of the boundary issue in the spring of 1846 reached the Pacific Coast, the claims by American settlers of Company lands at Fort Vancouver and elsewhere below the 49th parallel accelerated. The interaction between settlers and the Company over the following fifteen years is discussed in the section of this document covering the transitional period of 1847 to 1860.

Puget's Sound Agricultural Company

In March of 1832 Chief Factor McLoughlin and several other officers of the Hudson's Bay Company issued a prospectus for "The Oragon Beef and Tallow Company," which would not be associated in any way with the Hudson's Bay Company, but rather would be a private venture financed and operated by McLoughlin and his colleagues. McLoughlin confided to young doctor William Tolmie in the spring of 1833 that "...he [McLoughlin] thinks that when the trade in furs is knocked up which at no very distant day must happen, the servants of Coy. may turn their attention to the rearing of cattle for the sake of the hides and tallow, in which he says business could be carried on to a greater amount, than that of the furs collected west of the Rocky Mountains..." [110] The prospectus described a joint stock company designed for "an export trade with England and elsewhere in tallow, beef, hides, horns &c.," which would be developed through the purchase of seven to eight hundred head of California cattle for breeding stock to be raised and slaughtered in the Oregon Country. [111]

A copy of the prospectus was sent to Governor Simpson who, in the summer of 1834, forwarded it on to London with a recommendation that the Company--not Company employees engaged in a private enterprise--embark on such an undertaking. London flatly rejected the idea of its employees forming their own concern, but did embrace the idea of entering the cattle-raising business for profit, rather than as just a means to self-sufficiency for their Columbia Department--Simpson had actually mentioned the idea of eventually exporting foodstuffs raised in the Columbia to London after his west coast trip in 1824. [112] With the urging of Simpson, who believed cattle could become a "highly" profitable trade for the Company, the Governor and Committee now authorized £300 for McLoughlin to buy cattle--for the Company--but did not direct that the purchase be made immediately. McLoughlin saw no merit in pursuing his ideas for the benefit of the Company, and did not aggressively search for new stock. For a few years the idea was dropped; it was to resurface with the incarnation of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company in 1838-39. [113]

Although the Hudson's Bay Company's exclusive license for English trade west of the Rockies was not due to expire until 1842, the Governor and Committee decided in 1837 to attempt to secure license renewal, before a change in government could adversely affect the Company's monopoly. At the time, the Company's arrangement with the British government was under fire in Parliament, particularly since fur-trading was not seen as compatible with colonization. [114] To bolster its request, the Company stressed its intent to promote settlement and develop export trade through expansion of agricultural efforts, thereby increasing British interests and influence in the region and reinforcing its physical possession of the territory under dispute with the United States. Simpson reported from his North American headquarters that at Fort Vancouver, "...we are directing our attention to agriculture on a large scale, and there is every prospect that we shall soon be able to establish important branches of export trade from thence in the articles of wool, tallow, hides, tobacco, and grain of various kinds." [115]

The Hudson's Bay Company's changing relationship with the Russian American Company in Alaska provided an additional impetus for expanding agricultural efforts in the Pacific Northwest during this period. For several years the two firms had been engaged in resolving territorial fur trade disputes, and Baron Ferdinand Wrangell of the Russian American Company had expressed an interest in obtaining both British manufactured trade goods and foodstuffs from the Company. [116] Although a formal agreement was not reached until February of 1839, the Governor and Committee were, a year earlier at least, anticipating an agreement which would commit the Company to supplying the Russians with foodstuffs, and not incidentally, exclude American traders in the region. In May of 1838 a new license for a twenty-one year term was granted by the British Government, committing the Company to agricultural expansion.

In the spring and summer of 1838, Chief Factor McLoughlin, on leave in London, met with the Governor and Committee and George Simpson to discuss expanding agricultural efforts in the Columbia Department. To avoid possibly invalidating the Company's charter, which did not provide for using capital for agricultural purposes, a subsidiary enterprise, the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company, was formed; only stockholders and officers of the Hudson's Bay Company were allowed to purchase stock in the new concern. [117] A prospectus for the new business was adopted by a committee of Hudson's Bay Company officers in London on February 27, 1839, with Governor John H. Pelly, Andrew Colvile, and George Simpson listed as the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company's first agents. Under the provisions of the prospectus, the new company would purchase livestock, tools and other agricultural material from the Hudson's Bay Company. Chief Factor McLoughlin was appointed to supervise the new company, in addition to his duties to its parent concern, and was given a £500 annual raise.

Two Hudson's Bay Company establishments were sold to the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company. In March, 1839, McLoughlin was directed to begin aggressive agricultural operations at Cowlitz and at Fort Nisqually, near the present-day towns of Toledo and DuPont, Washington, respectively. Both properties were legally transferred to the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company after the British government granted the company deed of settlement, dated December 23, 1840.

The Hudson's Bay Company was politically committed to encouraging settlement. In addition, it was evident colonists were needed to develop the territory's agricultural potential. However, the Company was adverse to any disruption of the fur trade, and wished to control the number of settlers and their impact on the Company. The terms for immigrant settlers were generous with the loan of seed, livestock, and materials, but the offer allowed only for a lease of land, and one-half of any increase in livestock or agricultural produce, the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company to take the remaining half. [118]

The Company believed its former employees already established on farms in the Willamette Valley were one source of settlers for the lands north of the Columbia River. French Canadians on the Willamette had repeatedly requested the services of a priest from the Bishop of Juliopolis, head of the Roman Catholic missions east of the Rockies, located at the Red River settlement in what is now Canada. [119] In 1837 the Bishop asked the Company to assist the overland passage of two Roman Catholic priests to the Columbia region, which the Company agreed to do if the priests would persuade the Willamette settlers to relocate to the new farm areas north of the Columbia, conditions which were accepted. [120] However, these settlers had no interest in leaving their established and freely-owned farms and nascent communities. As McLoughlin wrote to London in 1840:

If there were more Prairie Land at the Cowelitz it would be possible to encourage emigration to that place but the Puget Sound Association requires all there is and though the soil is equally as good as that of the Wallamette the large extent of the Prairies of the Wallamette and the great abundance of Deer on them and their more beautiful Scenery causes them to be preferred to the Cowelitz and Settlers will never settle on it till the Wallamette is settled or till the wood at the Cowelitz comes in demand... [121]

In an attempt to reinforce Company claims north of the Columbia, responding to indications that a large number of Americans would be migrating to the Oregon Country in 1840 and to a series of resolutions introduced to the United States senate calling for assertion of title to the "Territory of Oregon" in 1838 and 1839, the Company began, in 1839, a campaign to encourage families at its troublesome Red River colony in Rupert's Land to migrate to the Cowlitz. Upon the unsanctioned reassurances by Chief Factor Duncan Finlayson that the colonists' new lands would be sold, rather than leased to them upon settlement of the boundary issue, in the spring of 1841 twenty-one families left Red River under the leadership of James Sinclair. After their arrival at Fort Vancouver they waited for a number of weeks before the party was divided, with fourteen families sent to Nisqually, and the rest to Cowlitz. [122] By the fall of 1843, all the families at Nisqually had left for the Willamette Valley, due to poor weather and subsequent poor crops, livestock disease, and lack of amelioration of their terms by the Company.

Ultimately, the Company's desire to protects its fur-trading interests--viewed as inimicable to settlement--subsumed the political and economic reasons for encouraging settlement by British subjects, and its colonization policy became one of resistance, rather than encouragement. The Puget's Sound Agricultural Company's objectives became strictly economic in nature, and its farms devoted to increasing trade and fulfilling the Russian American Company contract. During this period, the Company sent a small number of skilled laborers--shepherds, dairymen and the like--and families from England to assist with the Puget Sound Agricultural Company's farm projects; these were almost unilaterally engaged under labor contracts, as direct employees of the company.

By 1841 the Hudson's Bay Company's policy was to strictly limit agriculture at the Company fur-trading posts--including Fort Vancouver--to supplying the posts' own needs and for that of the shipping trade. The Puget's Sound Agricultural Company's farms were to be devoted to fulfilling its agricultural contracts and developing an export trade in "...wool, hides, tallow etc..." [123] In practice, however, the officers and servants who worked on the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company's farms, and the equipment used on the farms, were carried on the Hudson's Bay Company books. In addition, farming at the Columbia Department posts capable of producing dairy, beef, grain, and other products was not, during this period, reduced. Although production of grain and other crops increased steadily at Cowlitz Farm and livestock production and processing, particularly sheep and cattle, grew rapidly at Fort Nisqually, the annual results were not sufficient to fulfill the Company's contract with the Russian American Company or other planned export markets on their own, and were supplemented by production from the Hudson's Bay Company post farms, primarily Fort Vancouver, and through Company purchase of wheat from settlers in the Willamette Valley.

Apparently the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company sold its produce to the Hudson's Bay Company, which then marketed and distributed it. In 1844 the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company listed a profit for the first time, and in 1845-46 its shareholders received their first dividend. [124] However, accounting procedures for the divisions between the two companies appear not to have been clear cut--in 1841 the Governor and Committee told Simpson they wanted the departmental accounts between the two companies more distinguished--and it is not clear if the debt owed the Hudson's Bay Company for its initial transfer of livestock, agricultural materials and tools and labor, was ever completely repaid. [125] Because Fort Vancouver was the Columbia Department's principal depot and by far its largest farming operation, the division between Puget's Sound Agricultural Company activities at the post and the post's farming to supply in-country and shipping needs is not clear, but it is evident that Fort Vancouver plains were used to pasture Puget's Sound Agricultural Company sheep, and probably cattle, and that Fort Vancouver grain and other agricultural products, not grown on the account of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company, were used to fulfill contracts with the Russians and to send to other markets. Likewise, the dairies at Fort Vancouver were established and operated to fulfill the Russian American Company contract.

One goal of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company was to produce wool for the English market. A large number of sheep were imported from California, most of which were situated at Fort Nisqually, where eventually two Scottish shepherds were sent by London to improve wool production, and purebred rams and ewes were shipped from Great Britain in an attempt to improve the local stock. In 1839, 2,435 pounds of wool from Fort Vancouver were sent to London, followed in successive years by wool produced primarily at Nisqually. The ovine products were not a great commercial success. In 1844, the 8,000 or so pounds of wool and 608 sheepskins shipped from the Columbia were judged as wildly uneven in quality and size by experts examining it in London. [126] Although the sheep business came to be located primarily at Fort Nisqually, sheep farming continued to be a major activity at Fort Vancouver, at least through 1846. In the 1840s, a sheep farm was listed in Fort Vancouver account books, credited "on account" of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company; in Outfit 1845, six employees, including two shepherds, on the Fort Vancouver labor rolls were employed by the agricultural company. [127] Governor Pelly reported to Lord Palmerston of the British Foreign Office in July of 1846, that the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company had 1,977 sheep at Fort Vancouver, valued at £2,037.

Fort Nisqually

Fort Nisqually, located on the bank of Puget Sound, had been established as a Hudson's Bay Company fur-trading post in 1833, and was selected as a Puget's Sound Agricultural Company farm in 1839 because its site, near large, open plains, was suitable for grazing large numbers of livestock. In the winter of 1840-41 it was transferred from the Hudson's Bay Company to the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company.

Ultimately the farm at Nisqually may have included a total of 261 square miles--at least that was the claim in later testimony. [128] Similar to Fort Vancouver at the peak of its development, the farm at Fort Nisqually included sub-units or farms at varying distances from the main post and development. The post at Fort Nisqually was moved between 1841 and 1843 one mile north of its original site, where water was more readily available; development of the farm and its structures spanned over ten years. By the late 1840s, the central farm included a partially stockaded fort, with residences and storehouses for produce, gardens, about 220 acres of cultivated fields, barns, a slaughter house, sheepfolds, a piggery, a number of livestock pens, and a dairy, and dwellings and outbuildings at its satellite farms.

Before McLoughlin left Fort Vancouver on furlough in the spring of 1838, he sent Captain William Brotchie on the Neriede to Hawaii with a cargo of Fort Vancouver produce and timber, and instructions to purchase sheep. Brotchie eventually purchased sheep from General Vallejo in California, 634 of which survived the voyage north, and were landed at Fort Nisqually in the summer. [129] These rough California woolies became the foundation flock for the P.S.A.C. After the Company committed to large-scale farming, McLoughlin, as manager of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company, began to enlarge the Company's herds and flocks. Apparently, McLoughlin had been told to move cattle and sheep from Fort Vancouver to Nisqually and the Cowlitz Farm late in 1839; in March of 1840 he wrote Simpson, explaining he had not transferred the livestock to the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company because driving the cattle north in the winter would have resulted in the loss of many animals; he stated he would move them after an inventory at Fort Vancouver was completed, presumably that spring. [130] That summer, he sent clerk Alexander Simpson and the English farmer, James Steel, to California to purchase more sheep for the P.S.A.C.: they bought seven hundred ewes which were loaded on the Columbia at San Francisco Bay, and were brought back to Fort Vancouver in September. They were probably later driven to Cowlitz or Nisqually. In September of 1841 McLoughlin notified London that sheep and cattle were enroute from the south bank of the Columbia to Nisqually, after being delayed by spring floods and the need to keep herders at Fort Vancouver to work the annual summer harvest. [131]

Farming operations at Fort Nisqually were closely supervised by McLoughlin and, by 1842, by Chief Factor James Douglas, also stationed at Fort Vancouver. In 1841-42 Douglas sent a series of missives to the superintendent at Nisqually, Angus McDonald, with specific instructions; for example: "I wrote you on the 16th December to have the wheat field at the Dairy sown with Timothy seed and Clover, and also to set out turnip and Cole roots for seed plants, but I have yet to learn when these objects are likely to receive attention...it is essential to the prosperity of the future crops that the seed be in the ground at the very earliest season. The land should also be manured or the crop will yield a poor return: with this view the strongest of the cattle may be penned at the dairy, as early as the middle of February unless the weather should be severe, when it should be manured and ploughed for the purpose..." [132]

In an attempt to bolster British claims to the area north of the lower Columbia River, the Company brought colonists from the Canadian Red River settlement to Nisqually and to the Cowlitz Farm. The settlers were not impressed with the opportunities offered them, which included plows and other farming tools, loans of pigs, cattle and working oxen, and of seed for cultivation. In the fall of 1842 McLoughlin told London that wheat and pea crops in the Columbia Department were "not so good as usual..." and that the crops of the Red River settlers at Nisqually were "very bad," prompting five to leave for the Willamette Valley. McLoughlin said, "no man who can take a Farm in the Wallamette will remain at the Cowelitz or Nisqually..." [133]

However, livestock production on the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company farm increased steadily in the 1840s. The number of sheep at Nisqually rose steadily: in 1840, there were a little less than one thousand sheep pastured at the post; by 1845, there were almost six thousand sheep at the farm, and almost two thousand head of cattle, both numbers far exceeding the quantity of livestock located at any other post in the Columbia Department, including Fort Vancouver. [134] The shepherds at their outlying stations, were lodged in small wooden houses on wheels, which could be moved from area to area, along with the sheep, which were penned at night to protect them from wolves. The houses were prefabricated at Fort Vancouver in 1842, and shipped from there via the Cadboro to Nisqually. [135]

Cowlitz Farm

Cowlitz portage was the termination point of river travel from the Columbia, and the embarkation stage for the overland route north to Puget Sound. A large prairie was located about a mile from the landing, and from the mid-1830s on, cattle from Fort Vancouver were driven to the site to graze. In the summer of 1838, while Chief Factor McLoughlin was on furlough, James Douglas sent a herd of cattle to the Cowlitz from Fort Vancouver, with "Mr. Ross & eight men with a number of agricultural implements." [136] Farming at the new establishment was already underway when Chief Factor McLoughlin returned to the Columbia from England in 1839, with the instructions to begin intensive farming operations at the Cowlitz, which the Hudson's Bay Company sold to the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company. Chief Trader John Tod had been sent to superintend establishment of the farm in the fall of 1838, and by the time McLoughlin arrived at the Cowlitz in November of 1839: "...[I] found that Mr. Chief Trader Tod had sown 275 bushels of Wheat, which looked as well as any I ever saw he had 200 acres of new land ploughed and which has been cross ploughed during the winter and 135 acres broken up and rails cut and carted to fence these fields." [137] Hudson's Bay Company clerk John Work wrote a colleague, Edward Ermatinger, that fall: "Our friend Tod is superintending a newly established farm on an extensive scale at the Cowlitz..." [138]

The soil at Cowlitz was rich, and far better suited than that of Nisqually's for crop production. Over the years, the Cowlitz farm became the chief grain producer for the P.S.A.C. Land was rapidly put into production: by the spring of 1840, six hundred acres had been ploughed, and by the fall of 1841 one thousand acres were under cultivation. At the time of the 1846-47 inventory, 1,432 1/2 acres were under cultivation. [139] Crops included wheat, oats, barley, peas, turnips, beans, cole seed and potatoes. During later testimony before the British and American Joint Commission, a former employee stated that in 1846 about twelve hundred acres were enclosed "...and subdivided by fences and ditches, into fields of convenient size, say from fifty to one hundred acres. Portions of this land were laid down under cultivated grasses, and the pastures were fully stocked." [140]

Fort Vancouver Outposts

During this period, Fort Vancouver's operations extended far beyond the thousands of acres surrounding the depot north of the Columbia River. As previously noted, Cowlitz Farm and Fort Nisqually operations were closely overseen by Chief Factor McLoughlin and Chief Factor James Douglas from Fort Vancouver, as part of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company operations. In addition, the Company's influence and control from Fort Vancouver extended south, into the fertile Willamette Valley; to a large Columbia River island now known as Sauvie Island and to several other outposts in the general region of the post. Brief study of these satellites contributes to a greater understanding of Fort Vancouver's development during this period.

Willamette Valley

The small settlement of retired engages in the vicinity of Champoeg in the Willamette Valley in the late 1 820s continued to grow, with the assistance of loans from Chief Factor McLoughlin. In 1834 the population increased when the Reverend Jason Lee of the Methodist mission, established his mission farm, and a few hardy American settlers and freemen began to establish farms in the area.

The Hudson's Bay Company was an overwhelming economic presence, by virtue of its loans of cattle and seed, principally wheat. When the inward migrations of Americans to the Valley swelled in the 1840s, it was to Fort Vancouver that settlers turned for assistance. McLoughlin later stated that:

...When the immigration of 1842 came, we had enough of breadstuffs in the country for one year, but as the immigrants reported that next season there would be a greater immigration, it was evident if there was not a proportionate increase of seed sown in 1843 and 1844, there would be a famine in the country in 1845, which would lead to trouble, as those that had families, to save them from starvation, would be obliged to have recourse to violence, to get food for them. To avert this I freely supplied the immigrants of 1843 and 1844 with the necessary articles to open farms, and by these means avoided the evils. In short I afforded every assistance to the immigrants so long as they required it... [141]

The Company purchased the settler's wheat, raised from Company seed, and milled it at the gristmill at Fort Vancouver. By 1839, there was sufficient wheat production in the Valley for McLoughlin to agree to send a boat to accept the harvest in the Valley, at Champoeg. and a few years later, the Company built a storehouse for the grain at the site. In the mid-1840s, a busy river transportation system was in place to move wheat from the Valley to Fort Vancouver's mill: beginning in April, and continuing for five months, boats continuously moved up the Willamette River, laden with settler-raised wheat, which when processed, was sent to fulfill the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company's contract with the Russians in Alaska. By 1844, river trade in items other than wheat was also in effect--a shipment of five thousand bricks made in the Valley arrived at the post in August of that year. [142] A French visitor--Eugene Duflot de Mofrás--visited the Valley late in 1841, where he noted that:

Since the colonists [in Willamette Valley] have no outlet for the sale of their pructs except through the Company's forts, obviously the Company can arbitrarily set whatever price it chooses. For example, only two and one-half or three piasters a hecoliter are paid for wheat, and even at that price the colonists are forced to take in exchange for grain English merchandise on which the Company makes a considerable profit. [143]

Portions of Fort Vancouver's horse and cattle herds were grazed in the rich grasses of the Willamette Valley throughout this period. Horses were probably pastured there to supplement fur brigades traveling south. While McLoughlin was on leave in 1838-9, James Douglas sent a herd of Fort Vancouver cattle to the Tualatin Plains, pasture for which, he said, was "superior to any other" in the vicinity of the fort. [144] Poor weather and periodic flooding of the lower plains of Fort Vancouver made additional pasturage for the farm's vast herds a necessity. In addition, the bulk of the cattle lodged in the valley under the care of settlers belonged to the Company; with most of the offspring pledged to repay the loan from the Company, settlers' herds increased slowly. This situation was remedied somewhat in 1837, when long-horned cattle from California, driven by Valley settlers, were brought to the Willamette.

As continuing waves of American immigrants entered the Valley, the Company's hold on the economics of the region began to loosen. Independent merchandising operations and mills were established by enterprising Americans. When the Oregon Provisional Government was formed in the Willamette Valley in 1843, it was evident that the Hudson's Bay Company influence on the area had slipped; in fact, McLoughlin viewed it as politic to cooperate fully with the fledgling government. The Company, however, continued to purchase wheat from the Valley settlers to enable it to fulfill its contract with the Russians in Alaska for more than a decade.

The present-day town of Oregon City, located in the Valley at the falls of the Willamette River, was the selected as a site for a Company sawmill in the late 1820s, and construction on a mill race and other buildings began in the early 1830s, but limited manpower and a fire postponed further development until later in the decade. In 1842-43, McLoughlin had the site surveyed and named, and filed a claim to it in his name. After the establishment of the Oregon Country's provisional government in 1843, Oregon City was selected its first seat of government, and it was granted a charter by the provisional legislature, making it the first incorporated city west of the Mississippi River. It was to Oregon City that McLoughlin retired in 1845-6. The Company operated a sales store at Oregon City in the 1840s.

Sauvie Island

Nathaniel Wyeth was an American entrepreneur attempting to establish a fur-trading enterprise in Hudson's Bay Company territory. In 1834-35 he established a post, Fort William, on what is now known as Sauvie Island, near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, about five miles from Fort Vancouver. Underfunded and inexperienced, Wyeth was unable to break the Company's hold on the fur trade, and when he abandoned his business in 1836, he left his buildings and other improvements on the island in the care of Chief Factor McLoughlin, with whom he maintained good relations.

By 1838, the Company was utilizing the island to graze cattle and horses, where there was "abundant feed," although the livestock was moved from the island during the flood season--its highest point was only fifty feet above sea level. By 1841, four dairies were operating on the island to help fulfill the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company's contract for butter with the Russians in Alaska. By the end of this period, 1846, there were several outbuildings and dwellings on the island, associated with the Company's dairies, although squatters had, by 1845, already begun to appropriate land there. [145]

Government Island

Another Columbia River island, about six miles east of Fort Vancouver, was utilized by the Company post. According to William Crate, who built sawmills for the post during this period on a site opposite the island, Fort Vancouver's employees gathered grass on the island to feed to oxen stabled near the mills. The island, referred to as Goose Grass Island during this period, was later mentioned in the Company's claims for compensation from the United States Government as the "Saw-Mill Island." It was referred to as Miller's Island when the U.S. Army reserved its use for raising hay in 1850; by 1867 it was referred to by its present name, Government Island. [146]

Operations at Fort Vancouver

Overview

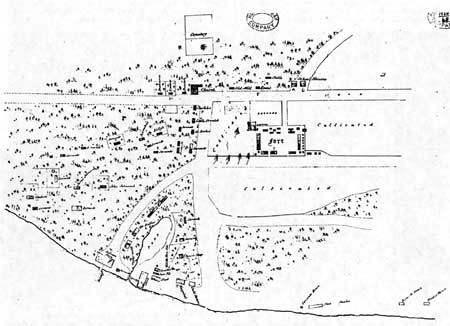

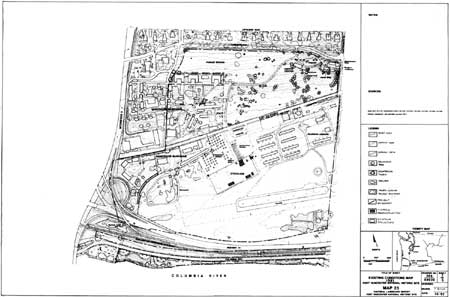

George Simpson's perilous canoe trip down the Fraser River enroute to Fort Vancouver in the fall of 1828 ended his plans to establish the Columbia Department's principal depot on that river. [147] With that scheme abandoned, and with the agreement with the United States to indefinitely extend joint occupation of the disputed territory, Fort Vancouver became the permanent supply depot for all of the department's posts in the Columbia and New Caledonia. The location of the original stockade, at least a mile from the Columbia River, was not practical for the increasing amounts of goods and material which would have to be moved in and out of the depot enroute to and from other posts, England, and, if the envisioned agricultural and industrial production plans materialized, Hawaii, California, and possibly the Russians in Alaska. Hauling water to the stockade, with an increased complement of employees stationed there to perform depot duties, would be inefficient. Also, as noted by several later visitors, a high, naturally-defensible site to repel Indians who, as it turned out, were mostly peaceful, was unnecessary. [148] Thus, in the winter of 1828-29, or possibly in the early spring of 1829, construction began on a new stockade on the plain lying along the river, about four hundred yards from its bank. [149]

Fort Vancouver: Headquarters of the Columbia Department

As noted previously, from this new site, Fort Vancouver became the supply center and administrative locus for an expanding number of fur-trading posts and two agricultural outposts. Returns from the Columbia Department and New Caledonia fur brigades were shipped via canoe and bateaux to Fort Vancouver, where they were inspected, prepared for shipment and recorded, and then loaded on the annual supply ships sent from London. From Fort Vancouver, annual supplies and trade goods for each post were ordered from London, and repacked, invoiced and shipped out to the posts. Over time each post came to rely more on produce raised "in country," including cattle, grain, and so forth, either from its own location, or from other posts, particularly Fort Vancouver, and later Cowlitz Farm and Fort Nisqually, a result of the policy formulated by Simpson and London to reduce the expense of transporting foodstuffs from London. McLoughlin's letters to chief factors and chief traders at various posts during this period often include specific instructions for agricultural production, for intra-post shipment of produce, seed and livestock, and for repairs of tools, structures and expensive manufactured items. As noted earlier, Fort Vancouver also administered a relatively short-lived merchandising venture in San Francisco (1841-45), and a trading establishment in the Hawaiian Islands (1833-1844). [150]

Headquarters of Coastal Trade

To conform with London's policy to maximize the joint occupation agreement with the United States, Fort Vancouver also became the base of operations for an expanded coastal trade, designed to compete with American ships, primarily operated from Boston, that carried on a provisioning and trade goods enterprise with the Russian American Company in Alaska, and direct trading activity with Indians along the Pacific Northwest coast. By the mid-1830s seven vessels, including a steamship, the Beaver, were operating along the coast, under the direction of John McLoughlin at Fort Vancouver; some of these were the annual supply vessels from London, which were dispatched to other Company ports before their return to Europe. The Marine Department also served to move provisions between Fort Vancouver and various trading posts, and were vital links in the industrial development at Fort Vancouver, used to ship lumber, salmon, and other goods--such as flour--to California and Hawaii, and later, Alaska, to transport livestock, and to import such goods as rice, molasses, and sugar.

Center of Agricultural Production

By the mid 1830s, agricultural production at Fort Vancouver allowed Simpson to tell London that: "The Farm...has enabled us to dispense with imported provisions, for the maintenance of our shipping and establishments, where as, without this farm, it would have been necessary to import such provisions, at an expense that the trade could not afford." [151] Agricultural production was a major activity at several other posts in the Department--notably Fort Colvile, designated as the principal supplier of the inland posts of the upper Columbia, and later, New Caledonia posts, and Fort Langley, which partially provisioned the coast posts with agricultural produce, and provided a substantial percentage of the salted salmon trade. Fort Nisqually (1833) and, later, the Cowlitz Farm (1838), both of which were folded into the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company, were established as agricultural production centers, both to provision the Hudson's Bay Company posts and to produce foodstuffs for export. It was, however, the Fort Vancouver farm, that was the center of agricultural enterprise during this period.

Early Industrial and Marketing Center

Governor George Simpson's acute eye noted the rich potential of natural resources in the Columbia region during his 1828-29 visit. During this period, Fort Vancouver became a hub of early industrial activity on the Pacific Coast, and an exporter and marketer of, in addition to furs, a variety of other products to foreign countries. In addition to salmon, noted above, the Company at Fort Vancouver became a major producer of flour, shipped primarily to Alaska, after 1839, but also to Hawaii and California, as well as to its own departmental posts. There was some trade in hides and tallow, and again, after 1839 and the establishment of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company, wool, although this principally came from the farm at Fort Nisqually. Nisqually and Fort Vancouver also produced butter for foreign trade. Another major industry at Fort Vancouver was lumber, milled at the post's sawmill, and shipped in the form of planks and deals to Hawaii and California. [152] Beginning in the 1830s, and expanding rapidly in the 1840s, Fort Vancouver became a merchandising center for imported goods, primarily sold--in exchange for wheat--to American immigrants; two additional sales outlets for goods were established under Fort Vancouver's aegis in the 1840s at Oregon City and in San Francisco.

Crossroads of Civilization

In 1836, Chief Factor Peter Skene Ogden, by then in charge of the New Caledonia District of the Columbia Department, wrote an associate:

When at Vancouver last summer I saw our Steam Boat and made a short trip in her....the Americans had four ships there... amongst the many good things their honours from Frenchurch Street [the Governor and Committee in London] sent us last summer was a Clergyman and with him his wife the Rev'd. Mr. Beaver a very appropriate name for the fur trade, also Mr. & Mrs. Coppindale [Capendale] to conduct the Farming Establishment & by the Snake country we had an assortment of Am. [American] Missionarys the Rev. Mr. Spaulding & Lady two Mr. Lees & Mr. Shephard surely clergymen enough when the Indian population is now so reduced but this is not all there are also five more Gent. [gentlemen] as follows 2 in quest of Flowers 2 killing all the Birds in the Columbia & 1 in quest of rocks and stones all these bucks came with letters from the President of the U. States and you know it would not be good policy not to greet them politely they are a perfect nuisance... [153]

During this period, Fort Vancouver served as the principal outpost of civilization in the North Pacific. It was the initial destination for almost all American and European visitors to the Pacific Northwest, including American missionaries and foreign scientists, and later American immigrants.

Scientists and Explorers

Fort Vancouver served both as the destination and home base for British, American and other foreign naturalists, many of whom became internationally-recognized scientists, with reputations based in part on their research from Fort Vancouver. To all Chief Factor McLoughlin extended assistance and aid. Among them, as noted earlier, botanist David Douglas, whose first visit in 1825-27, was followed by a second in 1829-30. Douglas was accompanied on his first trip by physician and scientist Dr. John Scouler. Botanist Thomas Nuttall, who travelled with the Nathaniel Wyeth Expedition in 1834-35 to Fort Vancouver, was recognized as the discoverer of many new genera and species of plants: his association with the Pacific Northwest is memorialized by the name given to the native flowering dogwood, Cornus nuttalii. With Nuttall was John Kirk Townsend, a Philadelphia ornithologist, who later acted as a temporary physician at Fort Vancouver.

William Brackenridge, at the post in 1841 with the U.S. Exploring Expedition, collected botanical data which was later published, including an important study of ferns. In fact, many members of the U.S. Exploring Expedition were guests of the Hudson's Bay Company, at Fort Vancouver and at other posts; some of the specimens from the collections of the expedition's naturalists and anthropologists, and the elaborate drawings, many of which were published in following years, were made at and near Fort Vancouver; the collections led to the establishment of the first federally supported museum, in the National Gallery of the Patent Office; later, they were lodged at the Smithsonian. John C. Fremont's overland exploring expedition from the United States, arriving at Fort Vancouver in November of 1843, included a collection of plants later described in a Smithsonian publication.

As noted earlier, the London Horticultural Society maintained close ties with Fort Vancouver via the Company's London office, and many native plants and trees from the Fort Vancouver region found their way into the Society's gardens at Chiswick. [154]

Missionaries and Immigrants

"...Vancouver the New York of the Pacific Ocean." missionary Narcissa Whitman recorded upon her arrival at the post in September of 1836. [155] Fort Vancouver, with its supplies of imported goods, agricultural produce, seed and livestock--not to mention its permanent buildings offering comparative comfort to recover from the rigors of travel--became the goal of missionaries, and later settlers, who began to filter into the Pacific Northwest in the 1 830s. The missionaries, despite the implications their arrival harbinged, were received hospitably.

A brief sketch of the role Fort Vancouver and John McLoughlin played in the settlement of the Oregon Country has been discussed. The operations of the post were, of course affected by immigration. Probably the most significant effects occurred during the latter years of this period, from around 1842 to 1846, when the numbers of immigrants and existing settlers in the Willamette Valley reached a certain critical mass. Taking the broadest view, it is obvious that the influx of Americans--some of whom were extremely vocal and had the ear of the likes of Horace Greeley and imperialistic politicians in Washington D.C.--was eventually bound to tilt the balance in the claims of the United States to the disputed territory. It was apparently hoped by McLoughlin that by steering settlers to the Willamette Valley, the British might yet retain their hold on the lands north of the Columbia River.

In 1837 U.S. Navy purser William Slacum assisted Willamette Valley settlers in driving a herd of cattle from California to the valley, a move which began to wean the settlers from the assistance of Fort Vancouver, at least in terms of livestock. More sheep, cattle and horses were brought north from California in 1842; the policy McLoughlin had established of obtaining repayment on his livestock loans with the increase of the settler's herds began to unravel. Settlers could no longer be relied upon to supervise herd increases for the Company. Until 1842-43, the immigrants had to rely on Fort Vancouver for supplies of clothing, seed and manufactured items. But around 1842-43, certain enterprising settlers in the Valley began to establish their own stores, loosening the monopoly on imported goods offered by the Company shop at Fort Vancouver, and one opened later at Oregon City. However, general merchandising from Fort Vancouver continued to be profitable for the Company into the 1850s, until American merchants became firmly established in the towns of Portland and Oregon City. [156] Also in the early '40s, some Americans began to establish their own flour mills, cutting into the milling operations at the post, although the Company remained the biggest purchaser of wheat in the Valley for a few more years, scrambling to fulfill its sales commitments to the Russian American Company in Alaska.

Activities within the Stockade

Discussions of life within the stockade has been addressed in some detail in the two-volume work by historian John Hussey, Fort Vancouver: Historic Structure Report, and has since been augmented by various other manuscripts, articles and reports.

One of the central points of activity within the stockade must have been the fur store--in its various locations during this period within the stockade--where furs from the entire department's brigades were collected and stored until shipment to England in the fall. This activity slackened when, in 1845, Simpson directed the bulk of the Columbia Department s furs be shipped to Fort Victoria, signalling the end of Fort Vancouver's role as the main fur repository for the Company. Furs arriving from outlying posts would have been unpacked, cleaned and aired, and then placed in storage in the fur store; they were apparently periodically removed from storage and beaten again to free them of insects, and given a final beating prior to baling on a fur press and shipment to London. Historic sources indicate the fur beatings took place out of doors, presumably in the courtyard, or behind the fur store, in an area enclosed by a fence. [157]

Another early activity would have been trading imported goods--shirts, cloth, tobacco, beads and so forth--for furs brought to the post directly by Indians. It is believed that at Fort Vancouver, natives were allowed access to a building set aside for that purpose, where bartering took place. Periodically, then, Indians would have been allowed access to the stockade interior for the purpose of trading. In addition, the Company maintained a sales shop, where it sold imported items necessary to its employees, both at Fort Vancouver and elsewhere within the department--clothing, pipes, tobacco and so forth. Later, as traffic in the Columbia increased, the shop carried goods for travelers and still later, settlers, most of whom purchased on credit, against wheat crops to be raised. In the 1840s, as settlers increased, the merchandise at the Fort Vancouver sales shop increased in variety and quantity.

Among the distinguishing traits of Fort Vancouver's physical structure was the presence of large warehouses. These were built as part of the post's function as the depot for the Columbia Department, where all goods destined for the subsidiary posts were stored prior to shipment: bales, cases, boxes and barrels of clothing, blankets, hardware, sugar, tea, medicines, and all the items necessary to conduct trade with the natives. In addition, all stock not on hand in the shop at Fort Vancouver was housed here, as well as Fort Vancouver farm products slated for later rations and use, or for distribution to other posts--grain, salted beef, seed. All these items were brought to the warehouses, tallied, stored, prepared for packing and disbursed throughout the year.

As the central depot for the Columbia Department, Fort Vancouver was the site of a great many other activities. A succession of bakeries provided bread for use at the post, and also biscuit for the Marine Department and for the forts on the coast. Blacksmith shops produced everything from hardware to ironwork required to repair and build ships, from agricultural implements to beaver traps. Carpenter shops made furniture, building parts, and probably repaired and made the wooden parts of agricultural implements, including wheels. Coopers made the thousands of barrels in which agricultural produce was shipped. Hamess makers made and repaired the saddles, hamess and pack gear necessary to keep the fur brigades and farm operating. "Everything," Charles Wilkes observed in 1841, "may be had within the fort: they have an extensive apothecary shop, a bakery, blacksmiths' and coopers' shops, trade-offices for buying, others for selling, others again for keeping accounts and transacting business; shops for retail..." [158]

Some agricultural functions were lodged in the fort--storage for salted meat was provided in a Beef Store for a few years in the mid to late 1840s. A granary was erected within the fort to store grain and flour for use at the post and for shipment as part of its export business. At least one root house was built within the confines of the stockade.

Administration of the Columbia Department and the Fort Vancouver farm took place in McLoughlin's office in the "Big House," or "Manager's Residence" (Chief Factor's house), and also in the two successive office buildings within the stockade. An enormous amount of paperwork was involved in the operation of the Department. Among the records required by the Company were journals of daily occurrences; correspondence books; inventories; indents from each post; returns from the fur trade; invoices and other related shipping records; accounts from each post; accounts for employees, and many other records. [159] Clerks and apprentice clerks labored long hours over the documents.

Subordinate officers of the Company, their families, and most visitors were housed in the structure, or range of structures referred to as the Bachelors' Quarters, and at times in various other buildings within the stockade, fitted up to provide housing--William Tolmie, who arrived in 1833, was apparently temporarily lodged in one of the buildings used as a store. When London sent the post a chaplain, in 1836, the Rev. Herbert Beaver and his wife were eventually placed in a small "parsonage," where they lived until their departure in 1838; the building was then used by Catholic priests, and was replaced in 1841 by a larger structure referred to as the Priest's House, or Chaplain's Residence. It appears that adequate lodging was frequently in short supply within the stockade throughout this period: the demolition of the "old" office in the center of the 1846 stockade's courtyard was delayed because Captain Baillie, of the sloop, Modeste, was using the new office as a residence.

Eugene Duflot de Mofrás, a visitor from France in 1841, described activity in the Bachelor's Quarters: "Every evening the young employe's assemble in a room called Bachelor's Hall. Here they smoke and discuss their adventures, journeys and skirmishes with the Indians. One tells how he was reduced to eating leather moccasins; another boasts of such expert rifle-shooting that he aims only at a bear's mouth to avoid damaging the skin. Often Scotch airs will be varied by old French-Canadian tunes when the French spirit of gayety grips these hardy Highlanders." [160]

In 1838, the Rev. Herbert Beaver describing living conditions at the post with a jaundiced eye, reported "...indecent lodging for all classes...eleven persons in the same room, which is undivided and a thirty feet by fifteen in size and in which, with the exception of the man, who takes his meals at the mess, they all eat, wash and dry their clothes, none ever being hung out." [161] However, as de Mofrás observed, "Their quarters resemble barracks and are bare of all comfort reminscent of England. Furniture consists of a small table, a chair or bench, and a hard plank bed infested with vermin and covered with two woolen blankets. And yet this modest furniture seems the height of luxury to men who frequently live out in the open for two years or more at a stretch, of often spend weeks exploring rivers in open canoes, exposed to incessant rains and cold." [162] The Company's servants were, for the most part, housed outside the stockade, in the village now referred to as Kanaka Village.

In 1835 Rev. Samuel Parker wrote, "Half of a new house is assigned me, well furnished, and all attendance which I could wish, with access to as many valuable books. There is a school connected with this establishment for the benefit of the children of the traders and common laborers, some of whom are orphans whose parents were attached to the company; and also some Indian children, who are provided for by the generosity of the resident gentlemen..." [163] The school was established in 1832, with John Ball, a young American who had arrived with Nathaniel Wyeth's first expedition, teaching McLoughlin's son and other boys at the fort to read. Instruction was given under a succession of teachers. Some students boarded at Fort Vancouver, in the schoolhouse--later the Owyhee Church--sent by officers and clerks from throughout the Columbia District For some years the education was apparently free of charge, but by the mid-30s, some students, at least, were required to work on the farm to help defray the expenses of keeping them. It seems the school may have been discontinued for a time, beginning in 1843. There is some evidence to indicate a school on a reduced scale operated under the direction of the wife of clerk George Roberts in 1844, and later under the wife of British engineer Richard Covington, who arrived at Fort Vancouver in 1846-47. Late in 1843 or early in 1844, Chief Factor James Douglas, in consultation with George Simpson, began to plan for a school which would be supported by subscription to pay the salaries of a teacher. [164] Douglas directed the construction of two new school buildings north of the stockade, anticipating the new school, but these structures were still unfinished when the U.S. Army arrived at the post in 1849.

It was Company policy to require all residents of the posts in the Northern Department to attend religious services on Sunday. At Fort Vancouver, two services were held on that day in the dining hall of the manager's residence, or "Big House;" one was conducted in English by McLoughlin or a designated employee according to the Episcopal ritual, and one was read by McLoughlin in French for Roman Catholics. Visiting missionaries were invited to preach at Fort Vancouver after they began to arrive in the mid-i 830s. As noted earlier, in 1836 London sent the Rev. Herbert Beaver, an ordained minister of the Church of England, to Fort Vancouver. During the course of the minister's two-year sojourn at the post, antipathy developed between Beaver and Chief Factor McLoughlin regarding religious instruction of the fort's children and the "fur trade" marriages of the post's employees; when McLoughlin left on leave in the spring of 1838, originally satisfactory relations between Chief Trader James Douglas and the Reverend disintegrated. Beaver and his wife set sail for England upon hearing of McLoughlin's return from his furlough in Europe. [165] On November 24, 1838, two priests, Francois Norbert Blanchet and Modeste Demers, arrived at Fort Vancouver, dispatched by the Bishop of Juliopolis near the Red River in Canada, after negotiations with Governor Simpson and London. The first Catholic mass in "lower" Oregon was held the following day. The priests were given a building to use as a church within the stockade; the building was also occasionally used for Episcopal services. The priests resided at the fort when not administering to the missions and other Columbia Department posts; in 1842, two additional priests arrived in Oregon Country. Around 1844 the Company offered Father Blanchet a tract of land north of the stockade, and in 1845-46 a new church was built beyond the confines of the stockade.

Agriculture

The farm at Fort Vancouver was the first such large-scale enterprise in the Pacific Northwest. Its establishment was a matter of economics, intended primarily to reduce the reliance of Hudson's Bay Company posts in the country west of the Rocky Mountains on imported foodstuffs, the transportation of which was expensive. John McLoughlin later wrote, "...if it had not been for the great expense of importing flour from Europe, the serious injury it received on the voyage, and the absolute necessity of being independent of Indians for provisions, I would never have encouraged our farming in this Country, but it was impossible to carry on the trade without it." [166] When Governor George Simpson visited the Columbia region in 1824-25, he realized the country had untapped potential for exploitation--not only to service the Company's fur-trading posts, but to turn a profit by exporting surplus produce, diversifying the Company's operations on the west coast. In addition, it was thought that agricultural development would eventually attract British immigrants, which would in turn bolster Great Britain's claim to the disputed territory.

George Simpson arrived at Fort Vancouver in the fall of 1828 on his second inspection trip. Highly satisfied with the progress of the Fort Vancouver farm, he wrote McLoughlin in March of 1829:

The farming operations at this Establishment are of vital importance to the whole of the business of this side of the Continent and the rapid progress you have already made in that object far surpasses the most sanguine expectations which could have been formed respecting it. That branch of our business however, cannot be considered as brought to the extent required, until our Fields yield 8000 bushels of Grain p Annum, our Stock of Cattle amounts to 600 head and our Piggery enables us to cure 10,000 lb of Pork pr Annum. I am aware that some little dissatisfaction has been occasioned by your refusing to Slaughter Cattle for the Shipping from England, but when both you and I can say that so anxious have we been to increase our Stock, that neither of us have ever indulged by tasting either Beef or Veal, the produce of Vancouver Farm, they have no cause to complain and particularly so when they get as much fresh Fish, Pork & Game as they can consume, with the run of our Gardens & Fields in fruit and Vegetables. [167]

His enthusiasm was communicated to the Board of Governor and Committee of the Hudson's Bay Company in London in a dispatch sent in the spring of 1829. London responded by commending McLoughlin for "...the success which has attended your exertions in Agricultural pursuits and raising Stock..." in a communication sent him in October of 1829. [168]

Simpson was, by this time, considering using Vancouver's agricultural production as an economic/political tool to help drive American maritime traders from the Pacific Northwest coast, where their vessels traded with Russian posts in Alaska and plyed the coast, trading with Indians for furs, in competition with the Company's operations. He told the Governor and Committee "...we could furnish them [the Russians] with provisions, say Grain, Beef and Prk, as the Farm at Vancouver can be made to produce, much more than we require; indeed we know that they now pay 3$ p. Bushel for wheat in California, which we can raise at 2/-[Shillings per Bushel]." [169] A proposal to the Russians in Sitka, where the Company would supply grain and salted meat, was refused at that time. A decade later, however, Russian trade serviced from Fort Vancouver would be a cornerstone in the development and operations of the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company.

During this historic period, Fort Vancouver became the agricultural center of the Company's empire west of the Rockies. As noted earlier, Fort Colvile, established in 1825-26, was intended to provision the interior posts of the upper Snake and mid-Fraser Rivers: by 1830 it was close to self-sufficient, and by 1834 it was fulfilling its role as provisioner of the interior, including New Caledonia. Likewise, Fort Langley, located on the flood plain of the lower Fraser in 1827, in part to provision a series of coastal forts Simpson intended to establish, eventually succeeded in raising sufficient produce to supply itself and some other posts. However, Langley became most profitable as a salmon fishing and export center, and in the 1840s a dairy center providing butter for export to Alaska. Both Colvile and Langley received their agricultural materials--especially livestock--from Fort Vancouver. [170] Later, the farms at the Cowlitz, Fort Nisqually, and, in the mid-1840s, Fort Victoria, increased the Columbia Department's agricultural production. However, Fort Vancouver was the operational hub and main production post of all the Department's agricultural production.

By 1837, George Simpson was telling London:

The fur trade is the principal branch of business at present in the country situated between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific ocean. On the banks of the Columbia river, however, where the soil and climate are favorable to cultivation, we are directing our attention to agriculture on a large scale, and there is every prospect that we shall soon be able to establish important branches of export trade from thence in the articles of wood, tallow, hides, tobacco, and grain of various kinds.

I have also the satisfaction to say, that the native population are beginning to profit by our example, as many, formerly dependent on hunting and fishing, now maintain themselves by the produce of the soil.

The possession of that country to Great Britain may become an object of very great importance, and we are strengthening that claim to it (independent of the claims of prior discovery and occupation for the purpose of Indian trade) by forming a nucleus of a colony through the establishment of farms, and the settlement of some of our retiring officers and servants as agriculturists. [171]

Environmental Impacts on Farming