|

Fort Vancouver

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

IV. FORT VANCOUVER: VANCOUVER BARRACKS, 1861-1918

Administrative and Political Context

During this period the official curtain was finally drawn on the historic drama enacted by the Hudson's Bay Company in the Oregon Country, although it fell far distant from Fort Vancouver's Jolie Prairie.

Final Resolution of the Boundary

The Oregon Treaty of 1846 had left vague the westernmost boundary between the United States and Great Britain, through the San Juan Islands. By the late 1850s, both British--the Hudson's Bay Company--and Americans had settled in the islands, and both countries attempted to collect taxes and customs from the settlers. In 1858 Whatcom County, Washington, attempted to tax Company sheep grazing on San Juan Island; in 1859 a pig belonging to a Company employee was shot by an American who caught it rooting in his vegetable garden on the island, and who threatened to shoot any British authorities that might attempt to take action against him. The incident prompted General William Harney at Fort Vancouver, on his own, unsanctioned authority, to send a company of soldiers from the post to "protect American inhabitants," under the command of Captain George Pickett, later reinforced by troops under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Silas Casey. Three British ships, under the command of Captain Hornby, arrived at the island to reinforce British interests. The escalating tensions of the Pig War--which the sequence of events came to be called--was largely defused through an agreement reached between General Winfield Scott, sent from Washington D.C. to the Pacific Coast to take command of the Pacific Division, and Chief Factor James Douglas, by then in charge of the Hudson's Bay Company post at Victoria. The agreement, later sanctioned in Washington and Great Britain, allowed for joint occupancy of the islands until 1873. Both American and British troops occupied the island; eventually interaction between the two camps became one of parties, races and picnics. In 1872 the British and American governments agreed to the submit this final boundary issue dispute to arbitration by Emperor William I, who awarded the San Juan archipelago to the United States.

Final Resolution of Claims

Throughout most of this period, the Company set a price of one million dollars for their possessory rights--including Fort Vancouver, the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company farms, and other posts--of property left below the 49th parallel. Negotiations on these issues dragged on until 1863, linked to the settlement of the Northwest water boundary dispute in the San Juan Islands. An 1863 treaty allowed the companies' claims to be settled separately from the final boundary resolution, and it was agreed each country would appoint a representative to settle all claims provided for in the 1846 treaty. With the establishment of the British and American Joint Commission on the Settlement of Claims, the Hudson's Bay Company presented a claim of over five million dollars, which included Puget's Sound Agricultural Company lands and holdings, 1.2 million of which was an estimate of the value of the land and improvements at Fort Vancouver. It was not until September of 1869, after gathering voluminous testimony regarding the lands in question, that the Commission filed its awards, a total of $450,000 to the Hudson's Bay Company, and $200,000 to the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company. These monies were paid to Great Britain by the United States in the early 1870s, terminating the claims of the Hudson's Bay Company in the United States.

Puget's Sound Agricultural Company

During this period, the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company's operations were locally supervised and directed from Fort Victoria, where a small farm had been established in the mid-i 840s. In 1848 The British Colonial Office granted Vancouver Island to the Hudson's Bay Company; the terms of the grant required that the Company undertake the promotion of independent colonization. In December of that year, Chief Factor Douglas, under instructions from London reserved a large area of land for the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company on the southern end of the island. During the 1850s, the farms were operated by baliffs, hired and supervised by the company; it was during this period that most of the remaining livestock at Fort Nisqually were moved to Vancouver farms. As previously noted, the farms at Cowlitz and Fort Nisqually gradually ceased operations during the 1850s and '60s until the 1869 claims settlement: at Nisqually, Edward Huggins conduct a small company operation on the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company's much reduced acreage between 1856 and 1869, and at Cowlitz Farm, George Roberts occupied the central buildings and some acreage between 1859 and 1871. Farming operations on Vancouver Island were largely unsuccessful; by 1870 the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company was debt to the Hudson's Bay Company for £37,440, and by the mid-1880s most of the farm lands had been sold. In 1920, the original deed of settlement was replaced by a Memorandum and Articles of Association, and the company was registered as The Puget Sound Agricultural Society Limited. In 1934, the company, with no assets and no operations, ceased to be listed on the register of the Joint Stock Companies. [1138]

The U.S. Army at Fort Vancouver/Vancouver Barracks

With the withdrawal of the Hudson's Bay Company from the ruins of its much diminished site at Vancouver, the United States Army was left in control of the 640 acre military reservation it had declared in the 1850s, with the exception of the St. James Mission enclosure to which, along with its associated disputed donation land claim, the Roman Catholic Church laid claim. [1139] The story of the Fort Vancouver site during this period, then, is primarily associated with U.S. military activities in the region.

During the first half of this period the military forces at Fort Vancouver/Vancouver Barracks were generally engaged in enforcing U.S. government domestic policies throughout the Pacific Northwest. In the 1860s and '70s soldiers stationed at the post were primarily engaged in battles with Indians throughout the region and in escorting them to reservations. In the '70s and '80s, commanders at Vancouver Barracks organized and directed survey and exploring expeditions of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, which had been purchased from Russia in 1867. During the late '80s and throughout the depression of the last decade of the nineteenth century, the forces stationed at Vancouver Barracks primarily served as a police force, in Alaska and in Washington during episodes of civil strife. Beginning in the late 1890s, soldiers at the post were sent abroad large numbers from the post, as the United States entered into an expansionist foreign policy. Later, troops were sent to police foreign countries.

In 1887 the army evicted the Catholic church from the St. James Mission compound; the Holy Angels College building was used for a number of years by the army. In 1889 the old St. James church burned down. In the 1890s, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled the church was entitled only to the lands occupied by the mission--about one-half an acre--and not the 640 acres originally claimed, effectively ending an almost fifty year dispute between the church and the United States government over what had once been Hudson's Bay Company land. [1140]

Operations at Fort Vancouver/Vancouver Barracks

In the spring of 1860, Colonel George Wright, who had preceded Major General William S. Harney in commanding Fort Vancouver headquarters in the late '50s, returned to Vancouver to command the Oregon Department. [1141] The following year Wright was called to California to head Union troops preparing to leave for the Civil War, and most regular army troops were removed from the region. In 1861, the Departments of Oregon and California were folded into the Department of the Pacific, with headquarters in San Francisco. In 1865 the Department of the Columbia was established, with headquarters at Vancouver Barracks, which included Oregon and Washington and Idaho territories, under the Division of the Pacific. The Department of the Columbia's headquarters were moved to Portland in 1867, and remained there until 1878. Alaska was placed under the jurisdiction of the Columbia Department in 1870. In 1878, the Department of the Columbia headquarters were returned to Vancouver Barracks, where it remained until the U.S. Army reorganized in 1913. In 1879, the post's name was changed from Fort Vancouver to Vancouver Barracks, which it has been known as ever since.

Although Fort Vancouver fostered the careers of many young officers who were to become famous in the Civil War, troops stationed at the post during that war's years had little contact with the bloody battles raging a continent away. [1142] Most of the regular army units left the post for the war. To replace troops shipped east, the post was at first manned by companies from the California Volunteers; later it was garrisoned by volunteers recruited from Washington Territory and Oregon. The troops were generally occupied escorting immigrants enroute to Oregon and Washington and skirmishing with Indians whose lands were being appropriated.

After the Civil War ended, regular army units were once again sent to the post. Early in 1866 the Department of the Columbia was staffed with one battalion of the Fourteenth Infantry, three companies of artillery and seven volunteer infantry companies. One of the artillery companies was stationed, ironically, at American Camp in the San Juan Islands, where Great Britain and the United States had each posted troops pending the final settlement of the water boundary between Canada and the United States--a political remnant of the dispute which had led to the founding of the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Vancouver over forty years earlier.

In the late 1860s, the continuation of the post was in some doubt; the Department's headquarters were moved to Portland in 1867, and some army inspectors questioned its viability. In 1866, Brigadier General James F. Rusling, inspector for the Quartermaster's Department gave Fort Vancouver a scathing report: "Militarily considered it has ceased to be of value because of heavy settlement in that region and disappearance of Indians. As a depot of supplies facts and figures prove it useless. As a school for "practice" if such be deemed advisable on the north west Pacific coast it may be well to retain it, but San Francisco or Portland is preferable. Recommend early abandonment of Fort Vancouver as practically valueless to the Govt." [1143] However, the post was useful to the army as a staging area for military actions against periodic Indian uprisings in the region, and it remained in operation.

Between the mid '60s and the early 1880s, troops stationed at the post were largely engaged in rounding up the few remaining bands of Indians not living on reservations, or putting those who had escaped and were rebelling back onto the lands assigned to them. The first significant engagements in which Fort Vancouver troops participated during this period was the Modoc War on the south Oregon border, during which Major General Edward Richard Sprig Canby was murdered while on a peace mission to the Modocs, who refused to enter a reservation. [1144]

In 1863 the government attempted to persuade the Nez Perces to relinquish Wallowa, the lands granted them by treaty in 1855 when gold was discovered in the region; a smaller reservation in the Lapwai Valley was offered to their leader, Chief Joseph. The matter had simmered for some years, but the valley was finally ceded to the Indians in 1873. A change in policy reversed that decision in 1875, and, following a meeting in which a holy man of the tribe was arrested for stating he would not go to Lapwai, Nez Perces attacked settlers in the Salmon River country. Fort Lapwai sent two calvary companies to engage the Nez Perces, one of which was almost annihilated in a battle in June. The Department of the Columbia mobilized six hundred soldiers, including troops from Fort Vancouver, to capture Chief Joseph's band. In September, the Nez Perces were captured while attempting to retreat to Canada for the winter. In 1878 soldiers from Fort Vancouver were dispatched again to fight the Bannack Indians in Idaho and eastern Oregon. Some Indians captured in those battles were brought to Fort Vancouver and placed in the guardhouse. [1145]

In 1878, an army appropriations bill was passed by Congress, requiring all division and departmental headquarters to be located at forts or barracks. The headquarters for the Department of the Columbia were shifted from Portland, back to Fort Vancouver, leading to the first major period of expansion of the post's physical facilities since the early 1860s. A wave of new construction on the site followed in the first half of the 1880s, most evident today in the structures of what is now called Officers' Row. The following year the post was renamed Vancouver Barracks. [1146]

In 1881, General Nelson Miles arrived at Vancouver Barracks as the new commander of the Department of the Columbia. His aide-de-camp was First Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka, already known for his leadership in an exploring party that found the remains of Sir John Franklin's ill-fated Northwest Passage exploring party of 1847. Under orders from General Miles, Schwatka took part in an 1882-83 expedition to Alaska, crossing the Chilkoot Pass in 1883, and arriving at the source of the Yukon, which he navigated to its mouth. Other expeditions organized at the post included Lieutenant Symons' 1881 survey of the Upper Columbia drainage, and Lieutenant Henry T. Allen's 1885-86 reconnaissance expedition into the Copper River and Tanana Valley region, living off the country with his party. These early surveys provided information that later led to the Alaskan gold rushes, including the famous Kkondike gold rush of 1897. [1147]

The completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1883, which linked Portland, via the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company to central Washington, and thence to the east coast over both Northern Pacific and Great Northern routes, signalled the end of the Pacific Northwest's frontier era. Smaller army posts in the region were closed; reserve units at Vancouver Barracks could be rapidly transported at least partially via rail to any potentially troublesome spots.

Until the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, troops stationed at Vancouver Barracks were largely engaged in drills, and military instruction at the post. Some units participated in the survey expeditions previously mentioned, and in enforcing martial law in domestic uprisings. In 1885 and '86, troops were belatedly sent to both Tacoma and Seattle to assist civil authorities in controlling anti-Chinese riots. [1148]

In 1892 Vancouver Barracks sent five companies as part of a massive twenty company force of infantry called up by President Benjamin Harrison to control violence erupting as a result of a union strike against the Mine Owner's Protective Association (MOA) in Coeur d'Alene Idaho. The following year, Vancouver Barracks soldiers were ordered up to control a large group of unemployed Puget Sound workers who joined Coxey's march on Washington, and in 1894 troops were sent out to assist the Northern Pacific Railroad during the Pullman strike, part of a federal call up by President Grover Cleveland when the American Railway Union strike spread to twenty-seven states and territories. [1149] Other policing actions by Vancouver Barracks-based soldiers included escorting relief pack trains to Alaska during the turbulent gold rush years of the late '90s. [1150]

After the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, the Fourteenth Infantry, which had been stationed at Vancouver Barracks for fourteen years, and all other units of the regular army at the post were transferred, and the establishment was garrisoned by volunteer troops. During the conflict with Spain, the post was an important mobilization and training center for Oregon and Washington volunteers. After the war, troops were sent from Vancouver Barracks as part of the occupying force in the Philippines used to suppress the nationalist movement. Several well-known regiments--the Second Oregon and the Thirty-fifth Infantry Volunteers were recruited, organized and trained there. [1151]

Following the war, the military was reorganized, and the size of the United States' standing army was increased. Vancouver Barracks was selected to house an infantry regiment and two batteries of artillery. Funds were authorized for a major construction program to upgrade the facilities, which began in 1902-3, and continued through 1910. A number of the post's extant buildings date from this period. [1152]

In 1906, artillery troops from Vancouver Barracks were sent to Cuba to intervene in the nationalist movement rising there. In the mid-teens Vancouver soldiers were sent to Mexico to support U.S. intervention in that country's affairs, after Francisco Villas's 1916 raid across the U.S. border in New Mexico during the on-going Mexican revolution. [1153]

Until the outbreak of the Spanish-American war, social and recreational activities at Vancouver Barracks were largely limited to officers and their wives. The average soldier's life consisted of assigned duties, field marches, occasional parades, poor rations--supplemented in some years by company gardens, and off-duty drinking in Vancouver saloons. In 1897, a new building dedicated as a post exchange and an athletic field built north of the officers' residences erected in the 1880s, expanded recreational opportunities for the typical soldier at the post. During and after the war, when occupation troops cycled in and out of Vancouver Barracks, the frequency of parades, balls and band concerts increased to celebrate departures or returns of different regiments, and field day events, which featured such events as baseball, track, boxing became part of the annual cycle of events at the post. Officers took part in these activities, as well as receptions and balls for visiting dignitaries; polo matches were held on a field south of old Upper Mill Road, just east of the now-vanished Hudson's Bay Company fort. [1154]

In 1913, the military abolished the Department of the Columbia in a reorganization which eliminated military departments throughout the country. Vancouver Barracks became the headquarters of the Seventh Brigade, reporting to Third Division headquarters in San Francisco. One regiment was stationed at Vancouver Barracks. By 1916, as a result of troops sent to the Mexican border, about 150 soldiers were left at Fort Vancouver, later supplemented by recruiting drives as the war in Europe continued. During the World War I, the barracks became a recruiting station from which the 318th and Fourth Engineers and the 44th Infantry were formed and sent to France, but its principal role was to serve as an airplane materials manufacturing center under the direction of the Spruce Division of the Army Signal Corps. [1155]

Spruce Production Division

In November of 1917 the United States announced the formation of the Spruce Production Division, part of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, at Vancouver Barracks, with headquarters in Portland, Oregon. It was a home front activity designed to supply high quality spruce wood for the production of allied combat airplanes, utilizing the Pacific Northwest's large and accessible stands of old growth Sitka spruce. [1156] The division was placed under the command of an army captain, Brice Disque, who forged an alliance between the federal government and northwest mill owners to bring soldiers into the forests to log. [1157]

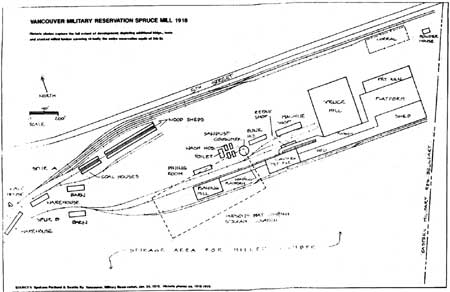

At that time, Vancouver Barracks was to serve as a training center for soldiers enroute to the forests of the Pacific Northwest, and to that end, infantry regiments stationed at the post were removed to make room for the thousands of "spruce" soldiers Disque planned to employ. However, early in 1918, the Barracks also became the site of the Cut-up Plant, the principal spruce mill of the Division, built and operated by spruce soldiers. Disque later said "There was not a commercial mill on the coast that was equipped to saw straight-grained spruce in the quantity demanded, and remain in business." [1158] Ultimately, there were six districts and sub-districts of the Division, located in Oregon and Washington, and many dozens of soldier camps, most of which were near lumber company camps, logging or building the miles of railroads necessary to reach remote stands of the premium Sitka spruce.

The mill and its associated structures at Vancouver Barracks eventually covered fifty acres south of old Upper Mill Road, including the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Vancouver site. Operations began on February 7, 1918; it had taken forty-five working days from ground-breaking to opening ceremonies. [1159] According to Disque, the entire plant cost $825,000. [1160] The Vancouver Barracks mill was the first of four mills that were to have been built in Oregon and Washington: two, one at Toledo, Oregon, and one at Port Angeles, Washington, were under construction in the summer of 1918, but were only around seventy percent complete when the armistice was signed. A fourth, to be erected in Washington's Clallam County from a dismantled mill in British Columbia, was in the process of being shipped when the war ended. The materials for the mills were later sent to Vancouver for storage and later auction.

The impact of the mill and the thousands of spruce soldiers that descended upon Vancouver Barracks was significant: a cantonment was built north of Officers' Row to house soldiers, and, as the mill geared up into production, tents and support buildings were erected around the mill on the historic lower plain to house and care for the spruce soldiers.

Special "Provisional Regiments" were formed--to operate the mill at Vancouver; to provide guard duty, and to provide motor transport. Major J.D. Reardan was placed in charge of the Second Provisional Regiment, responsible for building and operating the plant and kilns, including installing a sewage plant, and lighting system: by July of 1918, there were 2,400 troops housed at the mill site. The First Provisional Regiment was initially housed in the Upper Cantonment, and later transferred to the Barracks, where it provided guard and military police duties. The Third Provisional Regiment was primarily comprised of automobile mechanics and drivers, about half of which was stationed in the forests to keep trucks, cars, and ambulances running. A fourth regiment was stationed, briefly, at Yaquina Bay near Toledo, Oregon. The mill ran continuously, night and day; the soldiers worked six hour shifts.

When the armistice was signed in November of 1918, the Cut-up Plant had been in production for less than a year. Operations in the woods ceased on November 12, and all contracts with private mills were cancelled. Any timber already felled, or cants already manufactured was shipped to Vancouver. Some--but not all--Spruce Division Railroads throughout the two states were torn up and the equipment warehoused. Demobilization of the spruce soldiers began on December 3. When the war ended, the Cut-up mill at Vancouver Barracks had over four million feet of select airplane stock ready for shipment, and a portion of between twenty-five and thirty million feet of the commercially-suitable by-product ready for delivery. Eight hundred soldiers were kept at Vancouver Barracks to inventory and store the materials and equipment at the plant and those being shipped to the plant from the forests. The Division formed a Sales Board to market all major equipment and materials through sealed bid. It was, Disque claimed, "...the largest sale of Government property ever advertised, only the sale of equipment from the Panama Canal excelling it in number of items and valuation." [1161] The bids were low, and only about $200,000--valued at $12 million--of government property was sold. Some logs, the commissary stores which supported the spruce soldiers, and the commercial lumber that was the mill's by-product were disposed of, primarily through negotiation with private firms.

Site

General Description

During this period, all former Hudson's Bay Company acreage beyond the 640 acres of the U.S. military reservation, which centered on Fort Plain, fell into the hands of Americans. The small town of Vancouver, on the west edge of the military reservation, increased in population and became a shipping center for produce and lumber. The Company's former outlying farms, had, by 1860, largely fallen into the hands of Americans, but throughout this period, the functional uses of these sites continued to be agrarian in nature.

The most significant impact on the entire area was the completion of the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway in 1908, which linked Portland to Vancouver via a railroad bridge, crossed the military reservation at Vancouver Barracks along its south edge, and continued to Pascoe and Spokane in eastern Washington, where it connected to both Great Northern and Northern Pacific railroad lines to the Twin Cities in the midwest, and from there to points on the east coast. This impacted the spatial, organizational and functional aspects of the military reservation's site, but, more importantly, led to an increase in the importance and growth of the town of Vancouver as a shipping center, contributing to its dramatic increase in population. In 1912, the facilities for the newly-established Port of Vancouver were built along the river in the vicinity of the Hudson's Bay Company's Lower Plain Farm, and in 1917 the Interstate Highway Bridge was completed, linking Washington and Oregon via the Pacific Highway (Highway 99), which ran north-south through the town of Vancouver.

Circulation Networks

The principal routes leading from the military reservation in 1860, most of which were based on old Hudson's Bay Company roads, still served as primary arterials at the outbreak of World War I. Upper Mill Road (today East Fifth Street), crossed the reservation from east to west on roughly the same alignment used in previous decades; however, by the early 1870s, it was shifted slightly to the south at the west edge of the reservation, near the old quartermaster's depot, to align with the growing town of Vancouver's Fifth Street. To the east, it connected with a north-south road running along the east edge of the military reservation. Beyond the military reservation the roads to the Back Plains and to Mill Plain essentially followed the same routes established by the Company. A route to the north, Salmon Creek Road, in place by 1860, was still a main road in the teens. The road extending north to Puget Sound from the northwest corner of the reserve in 1860 had been rebuilt by 1914, although it followed much of the earlier alignment until it reached the northwest region of the army post, where, instead of swinging on a diagonal east towards the reserve, it continued south, connecting with Main Street in Vancouver, and forming part of the Pacific Highway.

The Military Reservation on Historic Fort Plain

During this period the 640 acres of the U.S. military reservation encompassing the Hudson's Bay Company's former Fort Plain farm underwent a gradual transformation. It no longer functioned as a trade center and farm, but as a military base, with some farming activities. However, up until the turn of the century, the changes in use were more a matte of degree than of abrupt alteration. For example, the area of cultivated fields and gardens just south of the Hudson's Bay Company's Upper Mill Road (today East Fifth Street), was periodically used as army company gardens through the 1890s, and the meadowland alont the river continued to be used to pasture army mules and horses until construction of the spruce mill in 1917. Such former Hudson's Bay Company functions as housing and feeding employees, caring for the sick, and administration were also performed by the military throughout this period.

The spatial organization of the site, however, changed dramatically during this period, responding to the changing role and internal organization of the army and to civilian developments as the region's population increased. Various areas of the post on the former Fort Plain underwent significant transformations throughout these decades: roads were realigned, removed and built, as land uses shifted; new building clusters were erected and new centers of activity established, while old ones were demolished; changes in vegetation were made to reinforce changes in use. [1162]

In the early 1860s, when the post was largely manned by volunteer troops, and the U.S.. military focus was on the war raging in the east, few alterations occurred on the site. After the war, the principal changes were the establishment of an ordnance reserve along the east edge of the reservation, separated from it by a fence which ran north-south to the east of the hospital and east barracks; the construction of a north-south line of forage barns roughly aligned along the previous route of the Hudson's Bay Company's "river road;" the construction of a new wharf along the river, and the reinforcement of connections to the town of Vancouver on the west edge of the military reservation. By 1869, maps of Vancouver Barracks showed no trace of the structures that had comprised the Company's Fort Vancouver stockade: the stockade site was contained within a large fenced pasture.

In the nine years between 1869 and 1878--when the Department of the Columbia headquarters were moved back to Fort Vancouver from Portland--and when the fate of the post was still in doubt, practically no changes were made to the post site or buildings, although some functions were shifted. During this period, the Ordnance Reserve was developed, with various quarters, storerooms and a guard house built.

Significant changes to the site occurred after the departmental headquarters were moved back to Fort Vancouver, beginning in 1879 and continuing through the end of the 1880s. During this decade, the post assumed an air of grace, with gardens, landscaping, and recreational facilities for soldiers. Military duties were not tasking, and soldiers were set to work on such duties as improving roads and cultivating gardens. The site's underlying network of roads and entrances, which was to last until construction of Interstate 5, were established at this time, and a number of its present historic structures, along what is now Officers' Row, were built during this period. The discontinuance of the Ordnance Reserve and arsenal in December of 1881, led to major changes in the landscape along the east edge of the reservation.

The structures built to house troops in the 1880s were inadequate to house the soldiers regiments raised to fight in the Spanish-American war, and to serve in other overseas operations which followed. In 1901, a new regiment--the Twenty-Eighth, was formed and recruited at Vancouver; in November they were shipped to the Philippines, but that summer most of the one thousand-plus man regiment had to be lodged in tents on former Fort Plain, due to insufficient housing at the post. In 1901-02 many soldiers had to live in tents or the old and disintegrating structures, such as the old battery quarters--later the calvary barracks, near the east edge of the reserve. After the war, the United States military was reorganized and the size of the standing army increased. Vancouver Barracks was selected to house an infantry regiment and two batteries of artillery. Funds were authorized for a major construction program to upgrade the facilities. Beginning in 1902-3, and continuing through 1910, the organization of the site was clarified through new construction, and thousands of square feet of new structures were erected, derived from standardized plans originating from the Office of the Quartermaster General in Washington, D.C. Like other military installations upgraded during the period, the majority of the post's new buildings were designed in the Colonial Revival style. A number of structures dating from this period stand on the grounds today. The assignment of the artillery batteries had a major impact on the development of the site, particularly in the construction of stables, wagon and gun sheds.

In 1903 the military granted an easement to the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway along the south edge of the reservation: between 1906 an 1908 the railroad company built their "North Bank" (of the Columbia) line, located on a berm--to raise it above flood level-along the easement, crossing the reservation to the town of Vancouver. The railroad had a significant impact on the south edge of the site, with the addition of railroad-related structures in the former pasture. The berm itself created a physical and visual barrier, effectively severing the historic relationship of the site to the Columbia River.

In 1917-18, construction of the spruce mill and its related structures had an enormous impact on the area south of old Upper Mill Road (today East Fifth Street), but very little effect on the garrison area between Officers' Row and old Upper Mill Road. Despite the need to house, feed and service thousand of "spruce soldiers" at the site, construction activity in the heart of Vancouver Barracks during this period was limited, no doubt due to the haste with which the program was put into effect and to the recognition of its temporary nature. Instead, a cantonment, erected in 1917 by Grant, Smith and Company of Chicago, which featured tent cabins and temporary structures, was built a mile north of the site, above Officers' Row, to house a regiment of engineers recruited at Vancouver, and the Vancouver District's military headquarters were located there; when the size of the Division was upped, hundreds of tents were erected on the site of the mill below old Upper Mill Road, and a variety of support buildings, including offices, mess halls, and latrines, were erected around the mill to service them.

Historic Hudson's Bay Company Stockade Site

By 1869, the Hudson's Bay Company's stockade was no longer indicated on army maps. The site was contained within a fenced area used as pasture, on the west edge of which, roughly aligned with the Company's former "river road," were a series of large forage barns, built in 1866, and enclosed within a fence. Maps in the 1870s show little change; the southernmost forage barn had been demolished by 1874. In the 1880s, after the Ordnance Reserve was discontinued, an elevated east-west road was built across the government pasture below the former Upper Mill Road (now East Fifth Street), and paralleling it, extending from what is now East Reserve Street to what is now McLoughlin Road. From maps of the period, it appears the road, built around 1883, crossed the northeast corner of the Fort Vancouver stockade site. As part of the amenities offered to soldiers at the post in the 1880s, a gymnasium was established in the northernmost forage barn; a building was moved to a position just north of the new gymnasium/old barn, and used as a canteen; the structures were enclosed by a fence. Both were demolished in 1889.

Construction of railroad spurs between 1906 and 1908 did not directly impact the stockade site; the spurs were to the north and west of the Hudson's Bay Company's fort's footprint. By 1905 a polo field had been laid out just northeast of the stockade; its southwest corner may have partially overlapped the northeast edge of the site.

The site of the Hudson's Bay Company's stockade and in-situ archaeological features were impacted by the spruce mill construction of 1917-18. Four railroad spurs crossed through the site, and at least three structures were entirely or partially erected on it. The planing mill and most of a loading platform along one of the spurs were located within the outline of the stockade, and a portion of the dining room and a huge kiln were located along the north edge of the site.

Garrison/North of Upper Mill Road

Major changes in this focal area of the military reservation will be addressed by decade.

1860s

The organization of principal buildings around the parade ground was reinforced during this period. By 1865, some new buildings had been erected, probably in response to the reassignment of regular army troops to the post and funds made available to western post after the war ended. The two westernmost of the log officers buildings along what is now called Officers' Row had been demolished, and three new frame structures built on their site; a fourth officers' quarters had been built just south of the hospital--by 1869 it was used to house the hospital steward; two other framed officers quarters had been built on the west edge of the parade grounds, north of the old log barracks and in line with the 1850s frame buildings. A new guard house--soon to be heavily used--was built in 1864, on the south side of the parade grounds, opposite the post commander's house. Several new company kitchens had been built behind the barracks.; In 1865, the Ordnance department began to build some structures east of the parade grounds and the line of structures behind the hospital. [1163]

While at the post in 1866, Brigadier General James F. Rusling, inspector for the Quartermaster's Department, noticed that "...a little southwest of the parade ground I observed several others [graves] that Col. Hodges told me were those of the H.B.C. me They were unenclosed and offended the eye by their publicity. I recommended these graves be removed to the post cemetery and that the cemetery grounds be at once put in complete order." [1164] By 1869, a small dwelling had been built for the ordnance sergeant on the site of the old Hudson's Bay Company graveyard; the army's post cemetery, a grubby site in 1866, situated west of the parade grounds, had been enclosed with a paling fence and shrubs had been planted and walkways established. [1165]

|

| Figure 17. Hudson's Bay Company stockade site (under water--note fir trees to left of photo) and east side of Vancouver Barracks parade grounds after flood of 1887. Octagonal structure in foreground is a guardhouse west of the Department of the Columbia Departmental Headquarters building (not visible). Fenced structure to right of guardhouse is cistern. In distance, the post headquarters and flagstaff are located on the parade grounds. Compare with Map 15. Courtesy Clark County Historical Society. |

By 1869, a number of structures had been built on the Ordnance Reserve, including a warehouse, a small workshop for blacksmiths and carpenters, and some quarters for the blacksmith, armorer and laborers. [1166] Behind the west barracks several new laundress' quarters had been built, and an artillery shed had been erected south of the barns. A loop road had been built behind the quarters and offices on the west side of the parade grounds, and additional laundress' quarters erected there. A small dwelling had been built for the ordnance sergeant on the site of the old Hudson's Bay Company graveyard. The easterly log barracks, built in 1849, had been demolished. The old artillery officers' quarters built in 1849 had been converted to a commissary and storehouse.

The parade grounds were enclosed by a low, single-rail, whitewashed fence; a path bisected the grounds, from the guardhouse on the south to the commanding officer's quarters on the north. A flagstaff was erected within the path, towards its north end. A picket fence enclosed most of the central area of the garrison, encompassing the officers' quarters on the north, the east line of structures behind the hospital, the offices and barracks structures on the west, and the scattered structures and gardens north of Upper Mill Road (East Fifth Street). Roads from Upper Mill Road towards the parade grounds were crossed by gates. Some company gardens were located in the southwest corner above Upper Mill Road, where the Hudson's Bay Company barn complex had once stood.

On the west edge above Upper Mill Road, what had previously been informal paths were now roads: From the intersection of Upper Mill Road and the road the army built through the Kanaka Village area to the river, a road to the north, skirting the west edge of the St. James Mission grounds was used to access the army's stables and points north; it would later become the north half of McLoughlin Road. What may have been a path from the army stables north of Upper Mill Road to a junction at the west edge of the reserve at Upper Mill Road, skirting the St. James Mission grounds, was, by 1869, identified as the "Road to Vancouver."

By 1866, there were a number of new buildings within the St. James Mission enclosure, apparently built under the direction of Mother Joseph, including a bakery and Holy Angel's College, a laundry, a carpenter shop, one building each for orphaned boys and girls, and a store building. The site had been fenced, with the mission's orchard occupying the southwest quadrant, the college the northwest quadrant, and the remaining structures, including St. James Church and the burial grounds, situated on the east half. The facilities, which, according to legend, were partially built with timber salvaged from abandoned Hudson's Bay Company structures, were crowded. At this time, the validity of the claim made by the church to 640 acres of land around the mission site was in doubt; it was on of many overlapping claims to the Hudson's Bay Company lands, and it was located on the reserve established by the army. [1167]

1870s

Until 1879, there were few changes in the area north of upper mill road, with the exception of the Ordnance Reserve on the east edge of the reservation: the changes beginning in 1878-79, with the decision to relocate the headquarters of the Department of the Columbia back to Fort Vancouver, will be discussed with the many changes that occurred in the 1880s. In 1874, a new post bakery was built west of its original previous site, below the Parade Grounds; the old sutler's store (post trader's building), along the depot road above former Upper Mill Road (now East Fifth Street) was converted to use as a theater.

The fence around the parade grounds was dismantled during this decade, and around 1874-75, some young trees were planted along the road skirting the south edge of the parade grounds, and in clusters on the grounds. Some older buildings were demolished, such as the old 1850s laundress quarters near the edge of the gardens, and a new north-south road was installed between former Upper Mill Road and the road just south of the parade grounds, passing to the west of the guard house.

On the Ordnance Reserve, a guardhouse and flagstaff were erected, and a large dwelling for officers was built northeast of the hospital. Additional structures built on this site included an ordnance storehouse, several laundress quarters, and possibly an office.

|

| Figure 18. Officers' Row, Vancouver Barracks, ca. 1886. Original log officers' quarters, standing next to newly constructed buildings, were demolished by 1888-89. Courtesy Clark County Historical Society. |

1880s

The first major upgrading of the post facilities in the area north of Upper Mill Road occurred in 1879-1880. It began with an appropriation for $56,000 "...to construct and repair officers quarters at Vancouver Barracks in Washington Territory." [1168]

In 1879, after the headquarters were moved back to the post, a number of new buildings were erected, and some changes were made in the organization of the site, the most significant of which were the establishment of roads and entrances to the east and west of the reserve, one on the alignment of the present Anderson Street, which led west to the town of Vancouver, and one extending the road past Officers' Row, Grant Avenue (now Evergreen Boulevard), to the east, through the Ordnance Reserve. In addition, all buildings were cleared from the west end of the parade grounds: two of the frame buildings were moved, one to the west end of Officers' Row, and one to the east end. The westerly 1849 log barracks were demolished, and the frame barracks were moved to the south edge of the now enlarged parade grounds.

New buildings for the Department of the Columbia headquarters were built to the south of Grant Avenue and west of the present McLoughlin Road, just north of the old stables and gun shed, which were demolished before final plans were made for the location of the new buildings. They consisted of three sets of double officers' quarters, and a large residence for the commander of the Department of the Columbia. The latter structure stands today. A new barracks building was erected south of the parade grounds, in line with the guardhouse. A new stable was built south of the parade grounds, and a new commissary building was erected south of the old log structure which had stood since 1849; the new commissary burned soon after completion and was rebuilt within a year. The sutler's store was converted to use as a theater, and the former ordnance sergeant's quarters became the Department headquarter's printing office.

On the east edge of the parade grounds, the hospital, laundress quarters and other structures in that north-south row, including the two-story frame barracks were moved or demolished in the early 1880s, as were all the Ordnance Reserve buildings to the east of them, opening up a vast expanse of open space on the east side of the parade grounds. In 1882, an ordnance storeroom was moved and "revamped" to serve as the departmental headquarters; it was sited at the far east edge of the reserve. [1169] Below it, a guard house, a mess building, and a gun shed were built. Quarters for the light battery unit were located south of these two buildings--there is some indication these quarters were in the old 1860s frame quarters, moved from the hospital row. In 1883, a stable built in 1879 just north of former Upper Mill Road was moved to a location south of the new Departmental headquarters. Initially used by the light battery, it was later occupied by cavalry horses, and then, after the turn of the century, when it was enlarged, by the artillery. [1170]

The old Depot road, which had served as the west edge of the parade grounds was removed by the mid-1880s, and the path which had bisected the parade grounds from the guardhouse to the post commander's dwelling was removed, although the flagstaff, shifted further south, remained along its axis. By the mid-1880s, then, the visual expanse of the parade grounds had been effectively doubled through the removal of the structures along its east and west edges, and through new structural enclosure nearer the boundaries of the reservation. The only structures to disrupt this open space during this decade were an octagonal bandstand, a fountain near the west end of the parade grounds, and a new post headquarters building, erected north of the south parade grounds road, opposite the old log post commander's dwelling.

A new series of officers' quarters were erected alongside of the 1849 log officers' quarters on Officers' Row. More officers quarters were built on the same alignment to the east, and to the west. Construction on these buildings began in 1884 and finished in 1889. Between 1887 and 1889 all but one of the log quarters were demolished--the old post commander's office, now referred to as the Grant House, was left standing and remodeled. The Departmental Commander moved into one of the new structures, now referred to as the Marshall House. In addition, two more sets of officers' quarters were built north of the 1879 officers' quarters. In 1887-88 a small post office and employees' quarters structure was built near the west entrance to the post. The line of Officers' Row now extended almost from the west boundary of the reserve to the east reserve edge. The buildings were enclosed with picket fences; hitching posts were installed in front of them. A boardwalk was installed between the fences and the road, and a fountain was installed in front of the Grant House. The maple trees lining Grant Avenue (present-day Evergreen Boulevard) were planted during this decade.

South of the parade grounds, New infantry barracks were built in line with the guard house along the south side of the parade grounds, and a new band quarters building was erected towards the east edge of it. A small theater was built in 1881 on the west end of the row, later used as a post school. The old printing office was converted into a school building.

The old sutler's store which had been used as a theater was converted to a quartermaster's storehouse, and commissary stores were moved into the quartermaster's 1879-80 building. The old log artillery officers' quarters were used as a mess house for a few years, and then demolished in 1888. By 1889, an area between the quartermaster's storehouse and the new commissary storehouse had been fenced, with a blacksmith's shop situated at the south end of the enclosure; in 1888, a new post commissary building was erected to the east of the enclosure. Thus, by the end of the decade, some of the principal quartermaster functions had been moved above the former Upper Mill Road from the old depot, although the commissary, ordnance officer and quartermaster dwellings were still located south of it. In the late 1880s, four small houses for non-commissioned officers were built in a north south line just north of old Upper Mill Road to the east of the quartermaster's area.

To the west of the south parade ground building line, where the post stables and artillery sheds had been located, three new infantry barracks were built. A new hospital was built near the west edge of the reserve, above what is now Hathaway Road, which had been installed around 1883. The St. James Mission enclosure was still extant in the mid-1880s, although by that time, Catholic Church activities had largely moved into the town of Vancouver, primarily under the auspices of the Sisters of Charity, and the church itself burned down in 1889. By that year, the Holy Angel's College building was in use by the army as a canteen, the former canteen structure just south of Upper Mill Road having been demolished.

1890s

In the 1890s, many of the principal extant roads and most of the entrances to the military reservation which were to serve until construction of Interstate 5 in the 1960s, were in place. The east-west road along Officers' Row, Grant Avenue (now Evergreen Boulevard), was completed in the mid-1880s. McLoughlin Road extended from beyond the north edge of Officers' Row south, forming the west edge of the parade grounds, and continuing to cross former Upper Mill Road (now East Fifth Street), and thence to the government wharf. What is now called Anderson Road had been built in the mid-1880s between McLoughlin Road and the west edge of the reservation; by the early 1890s, its west end looped north to join with Grant Avenue (now Evergreen Boulevard) to form a main entrance to the reserve, bounded by stone pillars. A secondary north-south road, now called Barnes Road, was completed by 1892, linking Grant Avenue with Hathaway Road, which ran east-west from McLoughlin Road to the west edge of the reserve. The south parade ground road, now McClelland Road, had been in place for decades; it extended towards the stables at the east end of the reserve, and then angled south to connect with Upper Mill Road. A north-south road, called Ingalls Road, crossed the parade grounds near its former east edge, connecting to McClelland Road. A road running on a northeast diagonal from the intersection of McLoughlin and old Upper Mill Road to McClelland Road serviced the area south of the parade grounds.

Very few adjustments were made to the post's physical plant during the 1890s. In 1892 a frame buildings was erected at the southeast corner of McLoughlin Road and McClelland Road to serve as a library, lecture hall and post chapel. It was later converted to barracks for the artillery band, but in the 1930s reverted to use as a chapel. A few miscellaneous latrines and an oil house for the quartermaster's yard were built during the decade. Some wood sheds were built along the north edge of Upper Mill Road; two on the former St. James Mission garden site, and two below the quartermaster's yard. The St. James Mission enclosure and remaining buildings had vanished by the end of the decade.

1900-1918

The decision to increase the size of the army housed at Vancouver Barracks, and to lodge the artillery units at the post, resulted in the last major wave of construction activity north of today's East Fifth Street; most of the principal buildings still standing on the present day reserve date from this period.

An east-west line of buildings, primarily double barracks each capable of housing 188 soldiers, was built along the south edge of the parade grounds, north of what is now McClelland Road, between 1903 and 1907. The old post headquarters built in 1885, the only structure that had previously jutted into the south edge of the parade grounds was moved further south to serve first as the Office of the Constructing Quartermaster, and later, in 1914, as headquarters for the Seventh Brigade. On its original site, a new administration building was erected in 1905-6. By 1914, a path had been constructed along the north edge of this line of structures, the construction of which had effectively narrowed the parade grounds. A line of young trees was planted along the north edge of the parade grounds, along Grant Avenue, and for a few years, a bandstand stood at the west edge of the parade grounds near the fountain; by 1914, a second bandstand had been erected opposite it, towards the east end of the parade grounds.

At the east end of the parade grounds, the clutter of old Ordnance Reserve structures which had been used to house the Departmental offices and support services, including the old cavalry barracks, were demolished by 1913, although the network of paths within the parade grounds which had been built to service the buildings remained until the 1930s. The area south of these structures and north of former Upper Mill Road (today's East Fifth Street) was redeveloped to service the artillery units. Beginning in 1902, with a major addition to the old artillery stables, by 1906 the area included an artillery guard house and a new stable capable of housing 134 mules and horses. On the opposite side of former Upper Mill Road a new ordnance storehouse was built in 1904, and two additional warehouses were erected.

In the triangle formed by McLoughlin Road on the west, McClelland Road on the north, and old Upper Mill Road (East Fifth Street) on the south, a series of adjustments were made in the uses of some buildings, and a few structures were demolished and others erected. The old band barracks was either demolished and rebuilt, or moved to a new site, east of, more or less in line with the new infantry barracks. [1171] While the 1880s frame barracks were retained, two older barracks on the south side of McClelland road, dating from the 1850s and '60s, were demolished in 1906. A new gymnasium, near McLoughlin Road; a new post exchange replaced the old canteen just south of the gymnasium; a new fire station towards the east end of McClelland, and a new bakery near the center of the area, were built during this period. In 1899 a bathhouse had been built near the northeast intersection of McLoughlin Road and East Fifth Street; in 1910 the building was converted to a laundry to serve the post. It was altered many times over the following years, but stood on the site until February of 1992, when it was demolished. The quartermaster's yard north of East Fifth Street was enlarged and rehabilitated with four new buildings erected between 1905 and 1910; also a coal shed to the east of the yard was built in 1904.

|

| Figure 19. Officers' Row, Vancouver Barracks, ca. 1912. Looking west down Grant Avenue (present-day Evergreen Boulevard), with Officers' Row on right and parade grounds on left (bandstand in mid-ground). Courtesy Clark County Historical Society. |

By 1914 this central area was more or less organized into functional units: the barracks were located along the north edge, lining either side of McClelland Road; the older 1880s barracks on the south side of the road were serviced by smaller company mess buildings located behind (south) them. The east edge of the area was bounded by the non commissioned officers' quarters and their fenced yards. The west edge of the site contained recreational, social and and general service buildings for soldiers, including the new gymnasium, post exchange and laundry, and, to the north, the older chapel and school/library buildings. The south-central area contained the quartermaster's yard, with its new and old storehouses and workshops, office, scale, oil house and wood and coal sheds. A general storehouse and bakery were located just east of the yard.

West of McLoughlin Road, several major new structures were erected, and by 1914, this area, too had been more or less functionally ordered. A new hospital was built north of the 1883 hospital in 1903-4, facing what is now Barnes Road, and the old hospital converted into barracks for hospital personnel; several residential structures were built or moved for the use of hospital personnel in the same area, and the hospital's stables, built in the 1880s, was moved further south to serve as a cow barn. In 1910, an older structure was moved across the street from the hospital and remodeled for use as a dental office. North of the new hospital, and just south of the main entrance to the reserve, a new guard house was built in 1903-04. The old workshops on the west edge of the reserve above East Fifth Street were remodeled. At the northwest corner of McLoughlin Road and East Fifth Street, on the site of Saint James the Greater Church and the mission claim, another artillery stable was built in 1910. Two smaller structures near the stable were built in 1903-4, later used as artillery storehouses. South of the 1880s infantry barracks located west of McLoughlin Road, a large new artillery barracks was built in 1903-4, facing what is now Hathaway Road.

Also during this period, a new set of officers' quarters was built in 1905 at the far east end of Officers' Row, and several new non-commissioned officers' quarters were built in the older residential complex north of Officers' Row. [1172] By 1914, the network of paths, and later boardwalks that had been established throughout the grounds had mostly been replaced with concrete walkways. Also, by the turn of the century, trees had been planted along McLoughlin Road north of East Fifth Street, and in the planting strips in front of the Officers' Row structures.

In 1917, an additional warehouse was erected in the quartermaster's yard, a new commissary east of the bakery was built, and an addition to the bakery was erected. A garage next to the 1911 fire station was also built in 1917, and the laundry was enlarged during this time. A small morgue was erected west of the 1904 hospital in 1918. [1173]

Historic Hudson's Bay Company Garden and Orchard Site

By 1869, the bulk of the Hudson's Bay Company's garden and orchard site were noted on maps as pasture. Along the west edge of the former orchard site, running parallel to the Company's "river road," which, by 1869, was not indicated on the maps, the army had built a series of large forage barns by 1866, enclosed by a fence. [1174] To the east of the barns, below former Upper Mill Road (now East Fifth Street), was a polygonal enclosure identified as "Hospital Garden" in 1869. The enclosure was situated at the north end of the Company's orchard site, and possibly the very northwest edge of the garden. According to the Covington drawing of 1855, there were still orchard trees extant in that location in 1855, and it may be that the hospital garden shown in 1869 included some fruit trees from the Company's orchard. Although the fence enclosing the hospital garden was in place as late as 1878, it is not known at this time whether a garden was cultivated within the enclosure during the '70s. The two old 1860s forage barns were still extant, but no longer enclosed by a fence. By 1874, the southernmost forage barn had disappeared; otherwise, this area experienced little change. A new military magazine, to replace the one dismantled on the discontinued Ordnance Reserve, was built south of the old forage barns, and enclosed with a fence; ordnance functions had been assumed by the quartermaster's department.

By 1883, as noted above, the northernmost forage barn had been converted to a gymnasium, and a structure had been moved to a location just north of it to serve as a canteen; the two buildings were contained within a fence, bordered by a short-lived new road on a raised grade, which ran east-west across the government pasture and the northeast tip of the old Company stockade. North of this road the former Hudson's Bay Company pasture was given over to a series of fenced company gardens; in 1882 it was estimated that sixty pounds of vegetables were harvested from the gardens daily. The powder magazine located on the east edge of the reserve, in the former Ordnance Reserve, was dismantled; for a time, a blacksmith's shop was situated near its former location. In 1889, the gymnasium and canteen buildings were demolished; the area above the road was still used for Company gardens in the early 1890s.

With the construction of the railroad spurs in 1906-08, the gardens were apparently abandoned. Maps after that period show increased railroad use of the site, including construction of a spur, scale, coal sheds and wood sheds over part of the former Hudson's Bay Company garden and orchard sites between 1907 and 1910. With construction of the spruce mill in 1917, and its associated structures early in 1918, use of the former Hudson's Bay Company garden and orchard area intensified, with the addition of seven additional spurs on the north and west edge, and one to the south. Tents, latrines and and sheds also covered a portion of the site.

Historic Hudson's Bay Company Field and Pasture Area

As previously mentioned, by 1869, the Hudson's Bay Company stockade site and the cultivated fields surrounding it were shown on the map as pasture. A north-south fence enclosed it on the west, roughly paralleling the Company's former "river road," and the north-south fence behind the hospital above former Upper Mill Road, continued below it to the river. To the east of that fence was additional pasture within the Ordnance Reserve; by 1869 a magazine enclosed by a "high wire fence," had been built just south of former Upper Mill Road near the east reserve boundary. As noted earlier, a road along the south edge of the reservation probably was in use by squatters who had land claims in the Company's south pastures and fields on Fort Plain in the 1850s; the road is not shown on maps of the 1860s, but it is shown in the late '70s and early '80s maps, which may indicate it never entirely ceased to serve as access across the south end of the reserve.

In the 1870s, the principal changes to the site were apparently in the Ordnance Reserve, where, in 1874, a "garden" was noted as extant just south of old Upper Mill Road in the vicinity of the magazine; by 1878 the area was shown as fenced, and what appear to have been roads are laid out within the area; at the present, the purpose of the roads is not known. South of the new east-west raised road crossing the reserve south of old Upper Mill Road--the road was damaged and finally washed out in a series of floods in the 1880s and 1890s--old Fort Plain was, as in previous years, given over to pasture. In the 1890s the pasture below the raised road was used as a skirmish range; revetments were built in the southeast corner of the reservation for military field practice.

The Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway, built between 1906 and 1908, across the south edge of the military reservation significantly altered the functional and spatial organization of the site. The introduction of railroad spurs onto the reserve shifted the way supplies were brought to the reserve, and in future decades a number of rail-related structures were erected on the site. The railroad berm across the south edge of the pasture was both a physical and visual barrier between the site and the Columbia River. On June 15, 1908, the steel work for a new railroad bridge between Vancouver and Oregon was completed, and the first trains crossed the bridge in November of that year.

At the north and west edge of the area south of old Upper Mill Road (now East Fifth Street), two warehouse sheds and an ordnance storehouse were erected around 1904, across the road from the artillery stables. By 1905, a polo field had been laid out northeast of the Hudson's Bay Company stockade site, and across old Upper Mill Road from the artillery and cavalry stables. Beginning in 1911, the army allowed a few civilians to use the polo grounds for experimental trial flights with airplanes, which were, in the first few years, packed and hauled to various sites in the Pacific Northwest, where they were then reassembled and "fitted up" for trial and exhibition flights. In June of 1911 Fred Walsh, a member of the recently-established Aero Club of America, tested a modified Curtiss biplane for a company chiefly owned by the Manning family of Portland, in two short flights over the polo grounds and the barracks. Despite a mishap in landing on the pasture, where "small hummocks" jolted the plane's wheels, Walsh said the ... "Polo field here is the best for aviation in any of the three coast states." [1175]

Spruce Mill

The former Hudson's Bay Company fields and pastures south of old Upper Mill Road were greatly affected by construction of the spruce mill on the site. The only logical location for the mill at Vancouver Barracks was on lower Fort Plain, which was already served by the S P & S railroad spur, and only had a few structures located along the spur towards the west end: the polo grounds were sacrificed to the war effort. By December 20, construction of the Cut-up Plant was underway, supervised by an Oregon mill owner, H.S. Mitchell, whose mill on the Columbia at Wauna, Oregon, was considered a model sawmill. [1176] Local mills supplied construction materials, and machinery was shipped in at great expense, and with haste, from all over the country. By January 7 the local newspaper was reporting that the mill was "...growing so rapidly and in such large proportions that the landscape is changed almost every twenty-four hours." [1177] At that time four of the mill's six units were "well along;" the frame for the fifth was in place, and the foundation was being poured for the sixth.

Operations at the mill began on February 7, 1918, complete with opening ceremonies featuring local politicians and army officials. It had been forty-five working days from the time ground was broken at the plant. [1178] It was a huge building, 358 by 288 feet; each of the six units contained two circular saw rigs, two table edgers, two re-saws and eight trim saws. The plant turned out between four and six hundred thousand feet every twenty-four hours, processing four to six inch flitches or cants shipped there from the region's forests: the milled lumber was then shipped to aircraft production plants out of state. At its peak, the mills saw between thirty-five and forty railroad cars of rived cants and sawn timber arrive daily. About seventy percent of the timber processed at the plant ended up as useful for aircraft; the remainder was used for smaller airplane parts, or was sold for commercial use.

The Spruce Division also extended a series of railroad spurs across the site to service the mill and kilns. Before the mill was completed, the Spruce Division approved the construction of a battery of drying kilns--the kilns covered an 100 by 350 foot area, and the drying sheds were 300 by 350 feet in size--on the site to season the cants, built within a two-month period. [1179] Those parts of the fifty acre site not covered by the mill, the kilns, timber sheds, and the thousands of tents and dozens of support buildings housing spruce soldiers, were devoted to storage of milled lumber and timber awaiting processing. Major facilities built on top of the Hudson's Bay Company stockade site included a planing mill, part of a loading platform, and several railroad spurs. A second major railroad spur (Spur B), was installed, beginning at the west edge of the original spur's curve, and crossing the site from west to east, dividing into additional spurs at various sheds and buildings. The original spur (Spur A), divided into seven lines, four of which ran parallel to old Upper Mill Road, across the north edge of the site.

|

| Figure 20. Cut-up plant of spruce mill on Fort Plain in early 1918, looking northeast. These huge buildings and associated rail lines covered most of the Hudson's Bay Company's stockade site. Long building at top left is a 1902 artillery stable, north of old Upper Mill Road. Courtesy National Archives. |

At the end of the war, after less than a year of operation, the mill was closed, and acres of both processed and raw materials were auctioned. Later, the remaining equipment and real property was sold. The cantonment north of Officers' Row remained standing, and was later used for Civilian Military Training camps. The Cut-up plant and its related structures stood on the site until 1925, when it was disassembled. In the 1920s, four of the Spruce Mill buildings were moved further east, to house reserve air squadron and other army air services that began after the war.

Quartermaster's Depot/Historic Kanaka Village Site

The army blacksmith's shop north of former Upper Mill Road, burned and was replaced in 1862 by a new blacksmith's shop west of the St. James Mission enclosure. At the end of the 1860s or in the early 1870s, the alignment of Upper Mill Road was shifted slightly to the south in the depot area, to connect with the town of Vancouver's Fifth Street. At least one new granary had been built between the quartermaster's stables and the carpenter's shop/wagon shed complex by 1869, and a new dwelling for the quartermaster officers had been erected south and west of the quartermaster's residence in 1865. An employee mess house for the depot was also built during the 1860s, but its location is uncertain. In the late 1860s, between one and three Hudson's Bay Company village structures were still standing: what is believed to have been the Fields house was located within an enclosure east of the pond near the river, and one or two buildings at the west edge of the military reservation, near the quartermaster's house, may also have been village dwellings. The four structures in the vicinity of the Quartermaster's house were all, by 1869, enclosed with fencing, according to the maps of the period. In the '60s, the westernmost end of the. Lower Mill Road extension, south of the Quartermaster's house, was still in existence, although it may have been realigned slightly to the south, but by the 1870s, it did not show on the maps.

In the 1880s, the west end of old Upper Mill Road was realigned further south, running below the site of the old wagon shed, but above the north-south line of granaries just north of the quartermaster's stable. The stable was altered to serve the needs of both the post and the depot. Above old Upper Mill Road, new workshops were built between 1883 and 1886, and north of them, several dwellings near the west edge of the military reservation. A new house for the chief ordnance officer was built in the depot area; it was later moved to the east of the quartermaster's house. In 1887-88 a new wagon shed was built east of the old granaries, the first of a new complex of vehicle structures on the site. The quartermasters residential area was improved with a semi-circular road leading from what became McLoughlin Road, and a bridge was installed to cross the ravine; all the yards were enclosed with picket fences. A new magazine and ordnance building were erected in the field to the east of McLoughlin Road. The road itself, south of Upper Mill Road, was lined with trees planted in October of 1882.

Just after the turn of the century, the old Quartermaster's Depot area underwent a major transformation to accommodate the two batteries of artillery assigned to the post. Three of the small frame buildings dating back to the 1860s, used for granaries and other functions, were moved to the east of the old quartermaster's stable, and a yard opened up, on the edges of which two new wagon sheds were built in 1906. The undeveloped area to the east of the wagon yard was fenced, and two long guns sheds built within it in 1904. A new stable was built just south of the old quartermaster's stable in 1909--the older structure, consisting of two buildings with an attaching shed, continued to stand until razed in 1935. The S. P. & S. railroad moved two army buildings, with the army's permission--the 1886-87 residential structure in the old quartermaster's residential area was moved to the east side of the old Ingalls house in 1906; the subsistence depot was moved further north in 1905.

|

| Figure 21. Southwest area of Vancouver Barracks, looking northeast, c. 1917. Old Quartermaster's Depot quarters in foreground, with 1909 stables behind. The railroad spur runs parallel to McLoughlin Road, then swings east, lined with warehouses and sheds. Compare this photo with Figure 22. Courtesy National Archives. |

When the S.P. & S. railroad line was built across the government pasture in between 1906 and '08, a rail spur on an elevated trestle which gradually sank to grade was built to service the southwest end of the military reservation 1906-07; it swung into a curve just east of McLoughlin road, and then doubled back to terminate near old Upper Mill Road, on the old Hudson's Bay Company orchard site. The army built a hay shed and granary along the east side of the spur's curve, opposite the quartermaster's stables, in 1905-06. In 1907 two shed-roofed coal sheds were built along the spur, on the site of the old Company orchard, followed in 1908 by two shed-roofed wood sheds near the terminus of the spur, where fuel for the post, now delivered by rail, was stored. In 1910, a scale and gable-roofed building to shelter it was added to the west of the coal sheds. By 1915 a wire fence has been installed along the spur, enclosing these service buildings and the two remaining 1866 forage store houses, to keep livestock out of the service area.

Construction of the spruce mill in 1917-18 had little impact on this area of Vancouver Barracks.

River Front Area

By 1869 the old Hudson's Bay Company wharf had been rebuilt by the army, and a road extended west from it along the river towards Vancouver. A sentry box was situated at the end of the 1850s army road, which was to become the lower half of McLoughlin Road, by 1869. As noted above, the east-west road along the river to the east was probably still in existence; maps show a portion of it extending to the east from the wharf area, but do not indicate that it continued beyond the pasture fence line. There was little change in the wharf area in the 1880s, with the exception of the previously-mentioned ordnance depot, which was built just north of the quartermaster's storehouse in the early 1880s, and enclosed with a fence in 1889. In the mid-'90s, the 1850s quartermaster's and subsistence depots on the wharf were demolished, and a new dock, a dock house, wharf and a breakwater were built on the site of the old wharf. In 1905 the ordnance storehouse was moved from its original site, further north and west by the S. P. & S. railway.

North of Officers' Row

A few structures had been built north of Officers' Row prior to this period, primarily on the east edge, as part of the Ordnance Reserve. A firing ground had been established along the west edge. In the 1880s, the area, which contained over half of the acreage within the reserve and was heavily wooded, underwent some development, particularly on the east side. Structures included officers' quarters, stables, and some workshops, all located in an area just north of Officers' Row. At the far northeast end of the reserve, a reservoir and pumping station were built in the 1880s. Dirt roads wound through the forest, and this largely undeveloped half of the reserve, particularly the east edge, became a favorite picnic and recreation spot, used through World War II. Just after the turn of the century, during the building activity on the rest of the post, more structures were added to the complex of buildings north of the east end of Officers' Row, including offices and quarters, and a concrete tank was added to the pumping station area in the northeast corner.

The firing range on the west edge was eventually discontinued, as the town of Vancouver's density increased near the site. In 1909 the army leased three thousand acres of land about thirteen miles northeast of Vancouver for use as a maneuver area and rifle range. The site was later purchased and named Camp Bonneville. In the 1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps built a number of structures on the Camp Bonneville grounds. The site was used for reserve training camps, and still serves that purpose, in addition to recreational use by the military and non-profit civilian groups.

In 1917, a cantonment of tent cabins north of Officers' Row was built to house units of the Spruce Division. West of the cantonment, just north of Officers' Row, the Victory Theater was built in 1918, which, during World War II, served as a recreation building. An athletic field north of Officers' Row was upgraded and used by the spruce soldiers: it was later named Koehler Field.

|

| Map 14. 1874 Ward Map. Map of the U.S. Military Reserve at Fort Vancouver, W.T., resurveyd by Lt. F.K. Ward. Hudson's Bay Company structures have disappeared. Courtesy National Archives. |

|

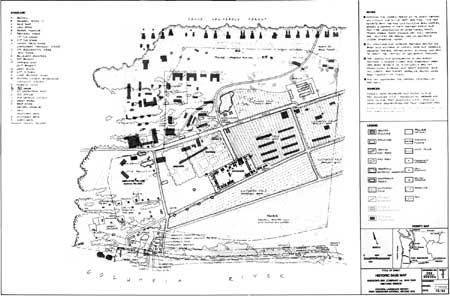

| Map 15. Plan of Present System of Water Supply at Vancouver Barracks, W.T., Compiled at Engineers Office, Headquarters, Department of the Columbia, 1886 (Building inscriptions enhanced for legibility). Vancouver Barracks after major construction in 1880s. A raised east-west road crosses the old stockade site: it can be seen in Figure 17. |

|

| Map 16. City of Vancouver, WA and Environs, September, 1891. C.A. Homan, City Engineer. This map shows the entire military reservation within the City of Vancouver. Courtesy Oregon Historical Sociey.. |

|

| (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|