|

Geological Survey Professional Paper 160

Geologic History of the Yosemite Valley |

Gates of Lodore

INTRODUCTION

THE OPENING of the West after the Civil War greatly stimulated early geologic exploration west of the 100th Meridian. One of the areas first studied, the Uinta Mountains region, gained wide attention as a result of the explorations of three Territorial Surveys, one headed by John Wesley Powell, one by Clarence King, and one by Ferdinand V. Hayden. Completion of the Union Pacific Railroad across southern Wyoming 100 years ago, in 1869, materially assisted geologic exploration, and the railheads at Green River and Rock Springs greatly simplified the outfitting of expeditions into the mountains.

The overlap of the Powell, King, and Hayden surveys in the Uinta Mountains led to efforts that were less concerted than competitive and not without acrimony. Many parts of the area were seen by all three parties at almost the same time. Duplication was inevitable, of course, but all three surveys contributed vast quantities of new knowledge to the storehouse of geology, and many now-basic concepts arose from their observations.

Powell's area of interest extended mainly southward from the Uinta Mountains to the Grand Canyon, including the boundless plateaus and canyons of southern Utah and northern Arizona. King's survey extended eastward from the High Sierra in California to Cheyenne, Wyoming, and encompassed a swath of country more than 100 miles wide. Hayden's explorations covered an immense region of mountains and basins from Yellowstone Park in Wyoming southeast throughout most of Colorado.

Powell first entered the Uinta Mountains in the fall of 1868, having traveled north around the east end of the range from the White River country to Green River, Wyoming, then south over a circuitous route to Flaming Gorge and Browns Park, and finally back to the White River, where he spent the winter. In 1869, after reexamining much of the area visited the previous season, Powell embarked on his famous "first boat trip" down the Green and Colorado Rivers. This trip was more exploratory than scientific; his second, more scientific trip was made 2 years later. Powell revisited the Uinta Mountains in 1874 and 1875 to complete the studies begun 6 years earlier. His classic "Report on the Geology of the Eastern Portion of the Uinta Mountains and a Region of Country Adjacent Thereto" was published in 1876.

King's survey—officially "The United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel"—is better known simply as the "40th Parallel Survey." King began working eastward from California in 1867. The Uinta Mountains region, however, was mapped by S. F. Emmons, under the supervision of King, in the summers of 1869 and 1871. Emmons' work was monumental, and although he emphasized in his letter of transmittal to King the exploratory nature of the work—as the formal title of the report indicates—his maps, descriptions, and conclusions reflect a comprehensive understanding of the country and its rocks. The 40th Parallel report contains the best, most complete early descriptions of the Uinta Mountains. It, indeed, is a treasurechest of information and a landmark contribution to the emerging science of geology.

Hayden visited the Uinta Mountains in 1870, descending the valley of Henrys Fork to Flaming Gorge in the fall after having earlier examined the higher part of the range to the west. Most of Hayden's observations were cursory, and he repeatedly expressed regret at having insufficient time for more detailed studies. In reference to the area between Clay Basin and Browns Park, he remarked (Hayden, 1871, p. 67) somewhat dryly that "the geology of this portion of the Uinta range is very complicated and interesting. To have solved the problem to my entire satisfaction would have required a week or two." Eighty-odd years later I spent several months there—looking at the same rocks.

Powell was perhaps more creative—more intuitive—than either King or Hayden, and his breadth of interest in the fields of geology, physiography, ethnology, and conservation was enormous. King's work, however, was distinctly more disciplined and reflected both his early professional training at Yale, perhaps, and the professional acumen of his subordinates. Powell was largely self-taught; Hayden was formally trained as a surgeon. Powell's reports are almost lyrical, but King's are more erudite, better organized, and more complete as to details than either Powell's or Hayden's. Hayden's reports are chaotic, possibly because he demanded and attained early publication of his findings. His practice was to publish annual reports and, to his lasting credit, most of his results appeared in print within a year of his fieldwork. So far as the Uinta Mountains are concerned, Hayden's thinking was more modern and more sophisticated than that of either of his colleagues.

One example serves to illustrate: The Uinta Mountain Group (Precambrian) rests on the Red Creek Quartzite (older Precambrian) with an angular unconformity of considerable local relief. A local relief of several tens of feet is evident in many places, and at several places it is more than 50 feet. At one place, the relief may be several hundred feet in a horizontal distance of about a mile. The early geologists who visited the area, especially Powell, made much of the supposed great magnitude of the unconformity. Powell deduced 8,000 feet or more of exposed relief, observing correctly the sharp local relief but apparently mistaking a fault to be an unconformable contact. Extrapolating further, Powell visualized that a lofty headland 20,000 feet high had been buried beneath the sediments of an ancient Uinta sea. King concurred. But Hayden's view (1871, p. 66) was much more modern: "I am inclined to believe that the immense thickness of quartz [Red Creek] was thrust up beneath the red quartzites [Uinta Mountain Group] carrying the latter so high up that they have been swept away by erosion." Red Creek Quartzite, we now know, was indeed uplifted relative to the Uinta Mountain Group by faulting. Although Hayden spent but a month exploring virtually the whole north flank of the Uinta Mountains, from the Bear River on the west to Browns Park on the east, he had an unmistakable grasp of the geology.

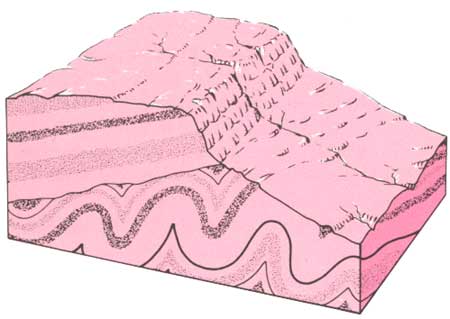

An unconformity. Ancient folded rocks eroded and overlain by tilted

younger rocks.

Other geologists of note visited the Uinta Mountains in the closing decades of the 19th century, about the time of the Territorial Surveys or shortly thereafter. In 1870 O. C. Marsh, a leading paleontologist of his day, began a study of the Tertiary vertebrates of the Green River Basin, particularly the rich faunas of the Bridger Formation. Marsh's study was made in open competition with E. D. Cope of the Hayden Survey. Marsh, of Yale University, was assured early publication in the American Journal of Science—published at Yale. Cope therefore resorted to telegraphing fossil descriptions to his publisher to protect his priority of discovery (Merrill, 1906, p. 598).

Marsh visited the Uinta Mountains briefly in the fall of 1870 and published a short description of his travels the following spring (Marsh, 1871, p. 191). Marsh Peak, looming above Vernal, bears his name. Heading south from Fort Bridger, Wyoming, Marsh followed Henrys Fork to its mouth. He turned east at Flaming Gorge to Browns Park, then went south to the Uinta Basin, staying well west of Lodore Canyon, via what is now Pot Creek and Diamond Mountain Plateau. Returning to Fort Bridger, he recrossed the mountains by way of the Uinta River and Sheep Creek Gap, probably skirting North and South Burro Peaks. From some point in his descent of the north flank of the Uinta Mountains, Marsh reported that "While descending the northern slope of the mountains toward the great Tertiary basin of the Green River, which lay in the distance, 2,000 feet below us, we passed over a high ridge, from the summit of which appeared one of the most striking and instructive views, of geological structure to be seen in any country. Sweeping in gentle curves around the base of the mountains, from near where we stood, many miles to the northward, was a descending series of concentric, wave-like ridges, formed of the upturned edges of different colored strata, which dipped successively away from the Uintahs; those nearest to us, 40° or more, those at a distance, seemingly but little—altogether a scene never to be forgotten." Marsh could only have been looking north toward Lucerne Valley, from Windy Ridge above Sheep Creek, with Jessen Butte to his left and Flaming Gorge to his right; this view is repeated nowhere else on the north flank of the range. Sheep Creek Gap, which, in Marsh's words (1871, p. 197), was "a narrow and almost impassable side ravine," now contains paved Utah State Highway 44.

Unusually rich vertebrate faunas in the Bridger and Uinta Formations attracted other paleontologists, among them Joseph Leidy, W. B. Scott, H. F. Osborne, and Earl Douglass. Leidy, whose namesake is Leidy Peak, south of Manila, collaborated with King. Scott and Osborne represented Princeton University. Later, in 1909, Douglass, of the Carnegie Institution, discovered the famous dinosaur-bone deposits north of Jensen, Utah, in what is now Dinosaur National Monument. These paleontologists were interested primarily in the fossil-bearing beds of the basins, particularly those in the badlands where rock exposures are maximal, concealment by soil or vegetation is minimal, and the chances of finding fossils are optimal. If they visited the forested valleys and ridges of the high mountains, they made little note of it, though after a hot day of digging in the badlands, they must have glanced wistfully at the snow-flecked peaks.

C. A. White reviewed the geology and physiography of the Eastern Uinta Mountains in 1889, using, of course, much from the works of Powell, King, and Hayden. White described the Eastern Uintas in some detail, particularly the folded rocks at the flanks of the range, calling attention to the unusual relations of geologic structure to drainage in the remarkable canyon country of the Green and Yampa Rivers. How, questioned White, were streams that were flowing in open valleys on both sides of the range able to establish and maintain courses across the mountains? Like Powell, with whom White had been associated in the field, White attributed the relations to "antecedence"—though he did not use the term—to a belief that the drainage preceded the folding and, through vigorous erosion, maintained its course as the mountains rose beneath it. In 1877 Emmons had expressed a contrary view. He believed that the course of drainage across the Uinta Mountains was superimposed from an earlier, simpler terrain—later eroded away—onto the present complex one. His view, with modifications, is favored here. The details of this bold concept are outlined on a later page. In brief, a stream initiates its course in a particular geologic setting, such as a sloping alluvial plain. Then, as it erodes downward it uncovers new, perhaps adverse, rock conditions at depth, but—being now held in by canyon walls of its own making—it is compelled to remain in its established course. "The sinuousness and irregularity of the course of the Green River through the Uinta Range, and its independence of the present topographic features of the region," said Emmons, "suggest that it must have been determined originally in rocks of an entirely different nature from those, through which it now lies."

C. R. Van Hise visited the Uinta Mountains in 1889 to look at the Precambrian core of the range. Van Hise was a leading authority on the Precambrian rocks of the United States, and he (1892, plate 8) showed insight in assigning the Uinta Mountain Group to the Precambrian at a time when most geologists still considered it to be Paleozoic. Powell apparently had already reached a similar conclusion as early as 1877, according to White (1889, p. 687 ).

The impact of the Uinta Mountains on early geologic thinking is hinted at by the names that were given to the great peaks. Most mountain ranges, by the names of their summits, honor the memories of statesmen, politicians, or explorers. The Uintas honor geologists. But to be a successful geologist in the third quarter of the 19th century, one perhaps had also to be a statesman and a politician, and certainly an explorer. Powell was all of these, and he excelled as each. Strangely, no Uinta peak bears his name, although he himself named many landmarks—mountains, streams, and canyons—throughout the Uinta Mountains and the Colorado Plateau.1 Powell's names are inclined to be imaginative and descriptive, if not downright dramatic—Flaming Gorge, Kingfisher Canyon, Beehive Point, Swallow Canyon, Canyon of Lodore, Echo Park, Dirty Devil River, Music Temple, and Bright Angel Creek, to mention but a few. He also changed the name of Browns Hole to Browns Park.

1After this bulletin was written,. I submitted the name "Mount Powell" to the Board of Geographic Names, for a previously unnamed 13,159-foot peak at the crest of the Uinta Mountains just east of Red Castle, between Henrys Fork and the East Fork of Smith Fork. This name has since been approved and will appear on maps published by the Government in the future. Also, the new 7—1/2-minute quadrangle map on which Mount Powell is shown is designated the "Mount Powell quadrangle."

No less than a dozen major Uinta Mountain summits bear the names of early-day geologists or topographers—Hayden, Agassiz, Wilson, Gilbert, Emmons, and King among them. Kings Peak, at an altitude of 13,528 feet, is the highest point in the State of Utah. Kings Peak, incidentally, is not on the main divide of the Uinta Mountains but rises from a subsidiary ridge a mile to the south.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1291/intro.htm

Last Updated: 18-Jan-2007