|

Geological Survey Bulletin 1309

The Geologic Story of Isle Royale National Park |

WHAT HAPPENED WHEN?

(continued)

THE GLACIERS TAKE OVER (continued)

Glacial Effects On Lake Levels

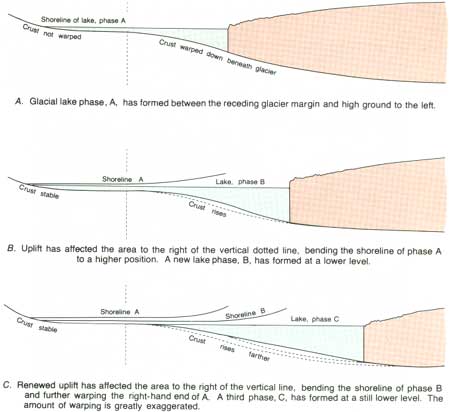

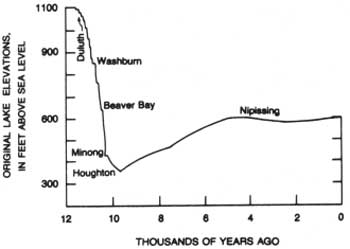

Some uncertainty exists as to whether the last ice readvance completely filled the Lake Superior basin. But however far the ice did advance, when it retreated it left behind a sequence of lakes that progressively filled more and more of the basin. The retreating ice uncovered successively lower outlets, and thus the general trend of lake elevations was initially downward. Later lake levels were influenced by uplift of the final lake outlet as the earth's crust rose in response to the removal of the weight of the glacial ice, weight which had previously depressed the earth's elastic crust when the ice advanced southward.

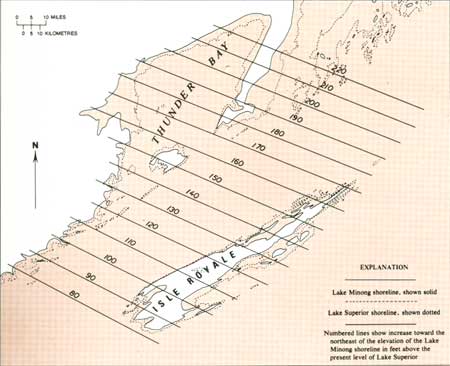

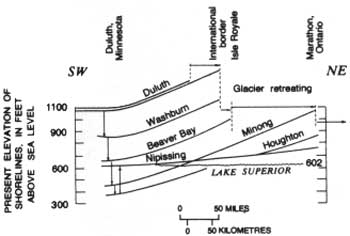

In between rather rapid changes in lake levels caused by changes in outlets, the water remained at stable elevations long enough for waves to erode cliffs, build beaches, and construct other recognizable shoreline features. The history of the sequence of lakes that occupied the Lake Superior basin has been deduced largely from matching their abandoned shorelines around the basin. Such correlation of shorelines is complicated by the fact that as the shorelines are traced toward the northeast, in the direction of ice retreat, individual shorelines gradually increase in elevation, owing to the rise of the land after the shorelines were formed (fig. 54). A specific example can be given by the shoreline of Lake Minong, one of the postglacial lakes. The elevation of its uplifted and warped shoreline on Isle Royale increases from about 80 feet above Lake Superior at the southwest end of the island to about 170 feet at the northeast end (fig. 55) a rise of over 2 feet per mile. Despite the complications introduced by tilting of the abandoned shorelines, through careful tracing of them, several distinct lake stages for the Lake Superior basin have been established and named. A shoreline diagram for the most important ones is shown in figure 56, and the chronology of lake-level changes is shown in figure 57.

|

| SHORELINE WARPING due to progressive uplift of the earth's crust as the glacier retreated (after Flint, 1971). (Fig. 54) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| UPLIFT AND WARPING of the shoreline of postglacial Lake Minong. (Fig. 55) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| POSTGLACIAL LAKE SHORELINE STAGES in the Lake Superior Basin. Curvature is due to crustal rebound (uplift), progressively greater to the northeast. Horizontal arrows indicate progressive retreat of the ice margin; vertical arrows indicate direction of changes in lake elevations. (Fig. 56) |

|

| LAKE-LEVEL CHANGES in the Lake Superior basin. Declining lake levels are chiefly due to progressive uncovering of lower outlets as the ice retreated northward. Rising lake levels are due to uplift of outlets by crustal rebound. (Fig. 57) |

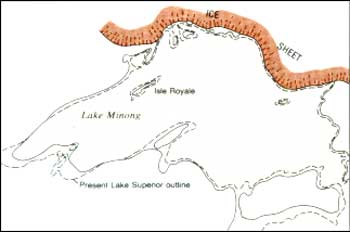

An important fact to remember is that on Isle Royale all shorelines older than the present one have been uplifted to a varying degree, and thus their present elevations above sea level do not reflect the elevations of the lakes that formed them. The original elevations of individual lakes can be determined only where the shorelines remain undeformed, south of the region of crustal rebound or uplift (at the far left of figs. 54, 56). Note, for example, that Lake Minong, whose shorelines are well displayed on Isle Royale above the present shoreline, actually existed at an elevation more than 150 feet lower than the present level of Lake Superior.

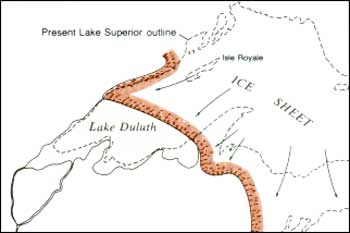

Lake Duluth was the first and highest glacial lake to fill a major part of the Lake Superior basin during retreat of the last ice (fig. 58). The ice sheet was in a period of rather rapid retreat when Lake Duluth formed, but it then must have slowed down because the immediately following lakes did not extend much farther northeast than Lake Duluth did, although lake levels fell nearly 500 feet between the levels of Lake Duluth and Lake Beaver Bay.

|

| LAKE DULUTH and its contemporary ice border, about 11,000 years ago. (Fig. 58) |

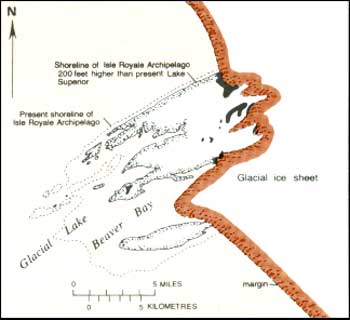

The ice front forming the north margin of the earlier lakes probably remained south of Isle Royale until about the time of Lake Beaver Bay or a little later, when it retreated to a position straddling Isle Royale west of Lake Desor (fig. 59). Abundant glacial till was deposited upon the newly emergent west end of the island, and the ice front remained stable long enough to build across the island the previously described complex of recessional moraines. Shorelines formed by the glacial lake associated with this ice front are found on the west end of the island where they now occur about 200 feet above the level of Lake Superior.

|

| GLACIAL ICE MARGIN during deposition of recessional moraines on Isle Royale and prior to complete northeastward retreat of ice from the island. (Fig. 59) |

Subsequent renewed and complete retreat of the ice margin from Isle Royale was rapid enough that only a minor amount of glacial till was deposited on the central and eastern parts of the island. When the ice margin reached the north edge of the Lake Superior basin, Lake Minong was formed, and the entire basin was filled for the first time since the readvance of the ice sheet (fig. 60). Lake Minong marked a relatively stable period in the history of the basin, and its beaches are among the best developed on Isle Royale. In fact, it was on Isle Royale that evidence for the existence of Lake Minong was first recognized.

|

| LAKE MINONG and contemporary ice border along the north shore of the Lake Superior basin, about 10,500 years ago. (Fig. 60) |

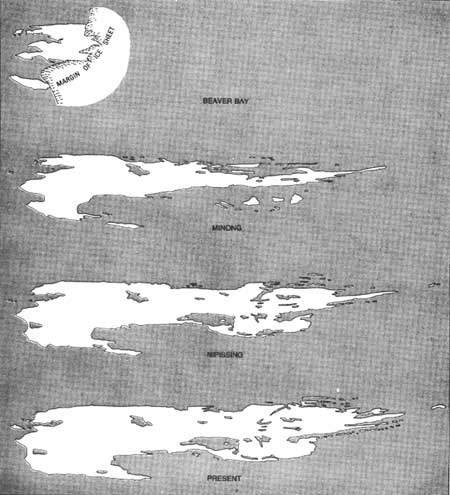

An even lower lake, Lake Houghton, followed Lake Minong. Then, during a long period, slowly rising lake levels controlled largely by crustal uplift resulted about 5,000 years ago in the Nipissing Lake stage at 605 feet above sea level (fig. 57), and finally the present Lake Superior evolved at 602 feet (fig. 61).

|

| BIRTH AND GROWTH OF ISLE ROYALE during selected postglacial lake stages. (Fig. 61) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

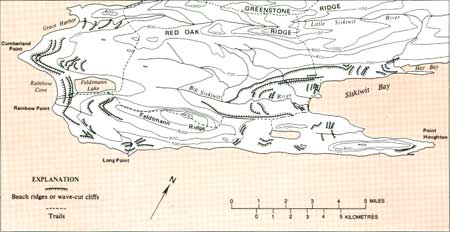

On Isle Royale, beaches of the postglacial lakes ancestral to Lake Superior are best developed on the southwest end of the island, where abundant glacial deposits provided easily worked materials for beach construction (fig. 62). Most abandoned beaches are not readily accessible to the hiker, but the trail from Siskiwit Bay to the Island mine crosses rather prominent Nipissing beaches about one-quarter mile from Siskiwit Bay. The trail from the Siskiwit Bay campground to Feldtmann Ridge follows a Nipissing beach terrace through a clearing marking the site of an abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camp and then climbs to a Minong beach, which it follows for about 2-1/2 miles.

|

| PROMINENT ABANDONED SHORELINE FEATURES on the southwest end of Isle Royale. (Fig. 62) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

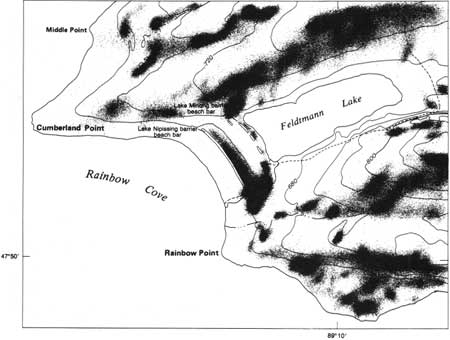

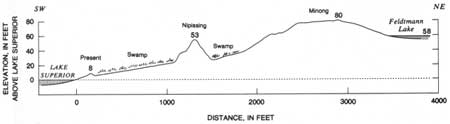

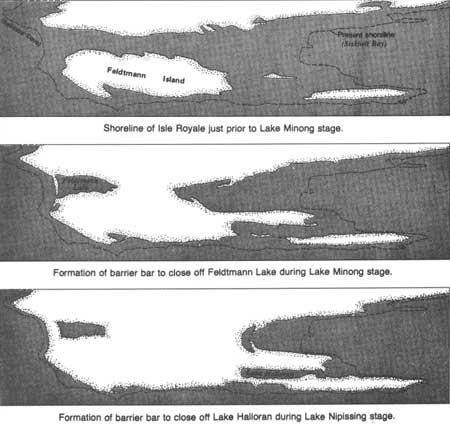

Among the best developed Minong and Nipissing beaches are those between Rainbow Cove and Feldtmann Lake; these are accessible from the trail between the cove and the lake (figs. 63, 64). Indeed, these beaches dam Feldtmann Lake. Just prior to the time of Lake Minong, the lowland between Rainbow Cove and Siskiwit Bay was covered by a glacial lake at a higher elevation, and Feldtmann Ridge was a separate island (fig. 65). As the water level fell to that of Lake Minong, the central part of this lowland emerged from the lake; however, Siskiwit Bay still extended inland about 5 miles more than it does today, and a similar bay on Lake Minong occupied the site of Feldtmann Lake. The Rainbow Cove area was exposed to the full force of storm waves from the southwest, and Lake Minong was at a stable elevation long enough for those waves to construct a barrier beach bar across the mouth of Feldtmann Bay and isolate it as a lake. Other beach bars were subsequently built at the lower levels of the Nipissing stage, including one that formed Lake Halloran.

|

| LAKE MINONG AND LAKE NIPISSING BARRIER BEACH BARS between Rainbow Cove and Feldtmann Lake. (Fig. 63) |

|

| LAKE MINONG AND LAKE NIPISSING BARRIER BEACH BARS (profile) between Rainbow Cove and Feldtmann Lake. (Fig. 64) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| FELDTMANN AND HALLORAN LAKES development. (FIg. 65) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

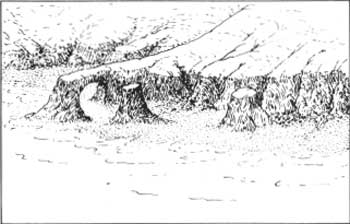

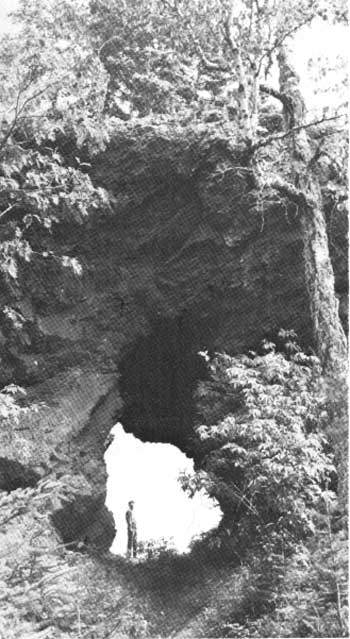

On the northeast end of Isle Royale, where glacially transported debris is limited and abandoned beaches are less evident, wave-cut features in the bedrock mark ancient shorelines (fig. 66). Prominent examples are Monument Rock, a stack associated with the Minong shoreline north of Tobin Harbor (fig. 67), and an arch cut through a narrow ridge crest on Amygdaloid Island (fig. 68), probably associated with the shoreline of the Nipissing stage. Suzy's Cave, on the north side of Rock Harbor about 2 miles west of Rock Harbor Lodge, may also be associated with the Nipissing shoreline.

|

| WAVE~CUT SHORELINE FEATURES including cliffs, stacks, and an arch. (Fig. 66) |

|

| MONUMENT ROCK, a stack associated with the shoreline of postglacial Lake Minong. Adjacent wave-cut cliff is just out of photograph to right. National Park Service photograph by Tom Haas. (Fig. 67) |

|

| WAVE-CUT ARCH on Amygdaloid Island, associated with the shoreline of postglacial Lake Nipissing. (Fig. 68) |

Except for wave-cut shoreline features, changes in the topography of Isle Royale have been very slight since the ice left. Materials derived from slope erosion are transported only very short distances, owing to low stream gradients and innumerable beaver dams. Bogs and swamps occupy much of the alluvial valley bottoms.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1309/sec5d.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006