|

THE RIVER AND THE ROCKS

The Geologic Story of Great Falls and the Potomac River Gorge |

TRAIL LOG—GREAT FALLS, VIRGINIA

This walking tour is designed to acquaint you with the important geological features that can be seen from the park trails. To help you find the stops that are indicated, small light-colored oval signs have been placed in strategic places to point your way. At each stop there will be similar signs that have the stop number on it. Length 2.14 miles.

| Mileage | FLOOD-PLAIN TREES | |||

| 0.00 |

Leave south entrance of Visitor Center. Cross old Patowmack Canal and walk to nearest overlook at the brink of the falls. |

| ||

| 0.12 |

(About 250 paces.) Stop G1. A closeup of Great Falls. The total drop of the river here from the uppermost rapids to the channel below this overlook is about 40 feet; the cascade directly in front of you is 16 feet high. The narrowest part of the channel below the falls here is 75 feet wide at normal stages of the river. The foam commonly seen below the falls is detergent suds—evidence of water pollution from towns and cities upstream. The rock here is metagraywacke, a type of metamorphosed sandstone. The conspicuous layers in this outcrop are the original layers or beds in which the sand was deposited on the sea bottom but which were turned on edge as the rocks were folded. The sand grains in some of the layers are as large as B-B's, but most of the sand is much finer. The same layers are plainly visible in the rocky islands in the middle of the falls. Note how the river channels follow the rock layers. Notice also the straight fractures or joints that cut across the rock layers. These joints formed as the rocks were uplifted and cooled. The most conspicuous joints are nearly vertical and perpendicular to the rock layers. These joints break the rock into blocks, making it easier for the river to quarry away the resistant layers. Each of the cascades in the falls marks a place where the river passes over a group of joints. Return to path along old Patowmack Canal, turn left and walk south (downstream). | |||

| 0.27 |

(About 320 paces.) Marker here shows level of 1936, 1942, and 1937 floods. In 1936 the water in the middle of the river was more than 80 feet deep. Turn left here and walk about 50 feet to overlook. |

| ||

| 0.28 |

(About 20 paces.) Stop G2. Vista of the falls and view of the old riverbed. The level surface on which you stand was part of the bed of the river before the gorge was cut and the falls were formed. From here you can trace the surface upstream and see that it becomes the present riverbed a few hundred yards above the falls. Notice the nearly right-angle turn in the river at this point. Above this point the river is following the rock layers; here it turns to follow a zone of weakness caused by closely spaced joints like those visible at Stop G1. Return to path along Patowmack Canal and continue south (downstream). | |||

| 0.42 |

(About 300 paces.) Large outcrop of rock in the trail. This rock is mica schist containing lenses and pods of white quartz. Notice how the layers are crumpled and folded. This occurred during metamorphism that converted the rock from shale to schist. This surface is part of the old riverbed. The exposed rock was rounded and smoothed by the river. Continue along same path. | |||

| 0.61 |

(About 400 paces.) Trail intersection at wooden bridge over old canal bed. Turn left off main trail. Walk about 125 yards and turn right on steep side trail leading down into small stream valley. Go about 10 yards upstream and cross creek. The narrow valley that you face in crossing the stream was man made, an early attempt to provide an outlet for the Patowmack Canal. The main valley was cut along a series of thin lamprophyre dikes, several of which are exposed in a small waterfall about 15 yards farther upstream. Scramble up steep trail on south side of valley. About 30 yards after crossing stream, turn right and follow trail south (downstream). |

| ||

| 0.75 |

(About 300 paces.) Stop G3. The Mather Gorge. The cliff below is about 65 feet high. The river here is about 220 feet wide and is 25 feet deep at normal stages of the river. Sight along the flat rock face toward the Maryland shore. You can see a series of deep vertical clefts in the cliff face which are dikes of lamprophyre. They look as though they should project across the river to about this point, but the extension of them on this side of the river is about 80 feet upstream. This offset is caused by a fault that lies beneath the river. The straight steep-sided gorge here has been cut by the river in the crushed and broken rock along the fault. The fault zone is more easily eroded than the solid rocks on either side. The rock here is mica schist. About 25 feet to the north (upstream) is a vein of quartz more than a foot thick. Gold was mined from similar veins at several nearby places on the Maryland side of the river. | |||

| ||||

| 0.88 |

(About 275 paces.) Follow narrow but distinct trail downstream along brink of gorge past river-smoothed outcrops of mica schist. At the junction of two trails, continue on 40 yards where a twin-trunked tree is living testimony of the flood of 1889 (the year of the Johnstown flood). The single inclined trunk grew vertically but was felled. The vertical trunks started to grow when the parent tree was felled. Their age tells us that the tree was felled in 1889 by a flood as large as that in 1936. Retrace steps to trail junction, turn left on crosstrail for about 40 yards to main trail along Patowmack Canal. Turn left (down stream). |

| ||

| 0.92 |

Ruins of lift lock on the Patowmack Canal. The lock is built chiefly of reddish-brown sandstone of Triassic age that was quarried near Seneca, 8 miles upstream from Great Falls, and carried downriver by boat. The same "Seneca Stone" was used in many of the older buildings in downtown Washington. At trail fork at lower end of lock follow right (upper) branch of trail. Beyond the trail entering on the left and to the next stop, you pass through a red oak and post oak forest, typical of the ancient riverbed which is now a bedrock terrace some 60 feet above the river. Also growing here are Virginia pine, cedar, pignut hickory, white oak, and chestnut oak. This type of forest is present on the flat surface above the cliffs across the river. |

BEDROCK-TERRACE TREES

| ||

| ||||

| 1.08 |

(About 350 paces.) Stop G4. Potholes. Here are several unusually good examples of potholes—circular holes ground in the rock by pebbles and boulders churned by the river when it was at this level. (See Stop G2, Maryland trail log, for a discussion of the formation of these holes.) Some of the pebbles left by the river can still be seen in the potholes and wedged in crannies in the rock outcrops. The small pond to the west, between here and the steep hill, was once a side channel of the river. Leave trail and walk over to edge of the gorge. Large potholes can be seen at the present river level and many smaller ones at the top of the cliffs on the Maryland side. Looking upstream you can see evidence of the effect of flooding on plant life. Near the tops of the cliffs the rocks are rough and sharp and are covered by several species of gray lichens. Some are leaflike, others are tight crusts cemented to the rock. The large ones that look like warty, gray potato chips are Umbilicaria. The light-gray, spreading ones are Parmelia conspersa. The gray crust that requires close examination to see is Lecanora cinera. The lichens are alive. If watered they turn soft and green in 5 to 10 minutes. Floods reach these levels only rarely, perhaps once every 10 to 20 years. About 20 to 30 feet below the cliff edge is an irregular band marked by dark-olive-green patches of moss (Grimmia laevigata). This species is common on many kinds of rocks in the Great Smoky Mountains and southern Blue Ridge; here it is growing at its northernmost limit. This zone is flooded about once every 2 years. Below the moss and extending down to 10 or 20 feet above normal water level, the rocks have a yellowish cast which is due to yellow and orange lichens (Candelariella vitellina). This zone is flooded several times each year. Near the base of the cliffs, just above normal water level, the rocks are covered with a metallic purplish-black coating that consists of iron and manganese oxides. Return to trail and continue south (downstream). |

SWAMP TREES

| ||

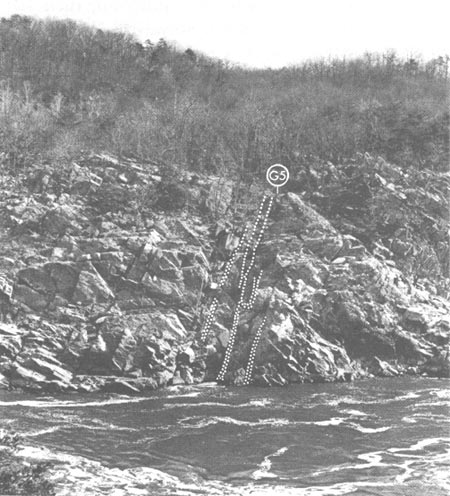

| 1.15 |

(About 150 paces.) Stop G5. A geological puzzle. Along the trail are many rounded pebbles, cobbles, and boulders left behind by the river when it flowed at this level. This boulder, 5 feet in diameter and estimated to weigh over 6 tons, is the granddaddy of them all! It is composed of a dark, heavy igneous rock called diabase, and the nearest outcrop of such rock is near Blockhouse Point, more than 7 miles upstream. This boulder is far too large to have been moved by even the most violent flood. Could it have floated in an ice jam or in a tangle of logs? Continue downstream about 20 yards, turn right on faint trail leading up steep hill. Scramble to top of hill and follow trail to the right, skirting brink of abandoned stone quarry on the left. Follow this trail for about 100 yards, then turn right again on main horse trail. Virginia pines are growing on disturbed ground along the edge of the quarry. Beyond and along the trail the forest consists primarily of oak species—white, black, scarlet, southern red, and chestntut oaks. Note that post oak is not present, and red oak and pignut hickories are rare. This forest is typical of a well-drained upland. |

| ||

| 1.30 |

(About 320 paces.) Stop G6. An ancient gravel deposit. The ground here is littered with gravel aud large rounded boulders, part of a river deposit even more ancient than those along the trail below. This deposit lies almost 120 feet above the present level of the river and must have been deposited during a very early stage of the cutting of the valley, perhaps 2 to 3 million years ago. Notice the deep gullies that run parallel to the trail. The trail here follows part of the old road to Matildaville. Like many heavily traveled dirt roads in the Piedmont, this one was subject to severe erosion. Water ran down the ruts left by wagon wheels, eroding gullies in the deep clay soil. When the ruts became too deep, it was easier to move the road to one side than repair the gullies. In some places this happened several times, leaving a series of parallel gullies. Follow trail north (upstream). |

| ||

| 1.41 |

(About 230 paces.) Deep gullies crossing road were probably caused by drainage from old field, now completely overgrown. The old field to the west is marked not only by a wire fence embedded in tree trunks, but also by the presence of Virginia pine. The pines are dying and falling, thus permitting the hardwood trees—oaks—to grow more rapidly. In and along the gullies, yellow poplar, a valuable timber tree, is predominant. This species is common in places where soil was severely eroded in the past. The forest from near the base of the hill to the Patowmack Canal is typical of areas that had heavy land use. Black locust with short stout spines, elm, and boxelder are common. The tree bristling with many-branched thorns is honey locust found only here. Many cultivated plants such as daffodils, day lilies, privet, and others indicate human activity. |

PIEDMONT UPLAND TREES

| ||

| 1.64 |

(About 500 paces.) Chimney and ruins of buildings at Matildaville. Turn right and follow trail back to path along old Patowmack Canal. Turn left and return to Visitor Center. | |||

| 2.14 |

(About 1,060 paces.) Visitor Center. | |||

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1471/sec6.htm

Last Updated: 01-Mar-2005