|

Geological Survey Bulletin 1508

The Geologic Story of Colorado National Monument |

HISTORY OF THE MONUMENT

THE STORY of how Colorado National Monument came into being is as colorful as the canyons and cliffs themselves. The fantastic canyon country had a magical attraction for John Otto1 (fig. 1) who, in 1906, camped near the northeastern mouth of Monument Canyon and began building trails into the canyons and onto the mesas—the high tablelands that separate the deep canyons. He did this back-breaking work simply because he wanted to and so that others could share the beauty of this wild country.

1For a very interesting account of this colorful character, see Look, 1961-62. My statements regarding Otto were taken mainly from this account.

In 1907 Otto got the Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce to petition Secretary of the Interior James A. Garfield to set aside the area as a National Monument. Otto's dream came true on May 24, 1911, when President William Howard Taft signed the proclamation creating the Monument. On June 14, Otto climbed to the top of Independence Monument (fig. 6) where he placed the Stars and Stripes to celebrate Flag Day. For several years thereafter Otto placed the flag atop Independence Monument on July 4th to celebrate Independence Day.

Until about 1921 the only routes into the Monument proper were John Otto's trails, but in that year the ranchers of Glade Park joined with Otto in building the steep, twisting Serpents Trail from No Thoroughfare Canyon to the mesa above—a much shorter route to Grand Junction. It had 54 switchbacks and climbed about 1,500 feet in 2-1/2 miles. The Serpents Trail was included in the Monument in 1933 and was used until 1950 when an easier route was built up the west side of No Thoroughfare Canyon and through a tunnel to the top of the mesa (figs. 3, 56). The Serpents Trail has been preserved as an interesting foot trail (fig. 55), which can be hiked downhill in an hour or so. A parking area near the foot of the trail allows one member of a group to drive ahead to await the others.

|

| JOHN OTTO, fantastic father of Colorado National Monument, and his helpers. Photograph courtesy Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce. (Fig. 1) |

In 1924 John Otto got the idea that the Monument should include a herd of big game, so he talked the Colorado Game and Fish Department into shipping six young elk, and he got the local Elks Lodge to pay the transportation costs. The elk were turned loose in Monument Canyon, but they found the sparse vegetation and scant water supply ill suited to their needs, so after a few years they found a way out over the rim and migrated about 20 miles south of the Monument to lush high country where they joined with native elk and multiplied to become the ancestors of the present fine herd on Piñon Mesa (shown in fig. 34D). Occasionally a few return to the Monument and may be seen mainly in Ute Canyon. Native mule deer are frequently seen in and near the Monument.

Far from being discouraged, Otto then hatched the idea to start a buffalo2 herd to be purchased by donations of buffalo nickels from school children and by contributions from the Odd Fellows and others. He finally raised enough money to get the patient Game and Fish Department to send him two cows and one bull. Unfortunately the bull died, so Otto talked the National Park Service into shipping him a bull from Yellowstone National Park. This time success crowned his efforts, and the small herd eventually multiplied to as many as 45 animals, but generally the herd has been kept at about 20-25 head ever since. You may spot some of them when you gaze down into Monument or Ute Canyons or when you drive past the northeastern boundary. Rarely, you may spot one in Red Canyon.

2So-called buffalo are actually bison.

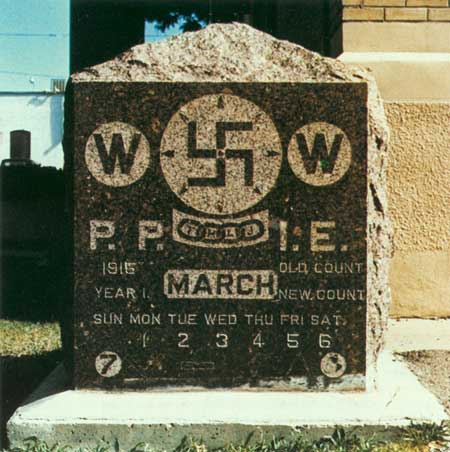

At the northeast corner of Fourth Street and Ute Avenue in Grand Junction is a most unusual object, which illustrates yet another peculiarity of John Otto—fantastic father of Colorado National Monument (fig. 2). Its history is best told by quoting from Al Look,3 though its purpose still remains a mystery.

One day a horse drawn dray backed up to a vacant lot on Grand Junction's Main Street [corner 6th] and unloaded a granite cube four feet square, carved on two sides. It weighed more than a ton and Otto supervised the setting.

One side [now facing west and not visible in fig. 2] showed a three foot circle containing a swastika with a five pointed star in each quarter. Above the emblem was carved "Rock of Ages" and below read "Cross of Ages." The second side [now facing south, and shown in fig. 2] was beyond normal comprehension. Two large W's on either side of a small swastika were over the letters or initials P.P., then four chain links with the letters T, H, L, J. inscribed, followed by the initials I.E. Below on the left was "1918," over "Year 1". On the right was "Old Count" and under it "New Count." Between them stands the word 'MARCH.' Below this are abbreviations for the seven days of the week with the figure 1 under MON ending with a 6 under SAT. The bottom line [most of which is barely visible in the photograph] contained the figure 7 in a circle, a carpenter's square, a small rectangle, probably representing a level, a plumb bob, a carpenter's compass and a circle showing the western hemisphere. That is all. It made sense to John Otto because from somewhere he gathered considerable money to have this monument carved by the local gravestone merchant. It stood for several years to mystify pedestrians, and was finally moved beside the Redlands road to the [east entrance of] Colorado Monument where it is now hidden by weeds.4

31961-62, p. 19-21.

4Just west of the T-intersection of Monument Road and the eastern segment of South Broadway.

|

| JOHN OTTO'S MONUMENT, at southwest corner of the Historical Museum and Institute of Western Colorado, at northeast corner of Fourth Street and Ute Avenue, Grand Junction. View looking north. Face is 4 feet square. (Fig. 2) |

It was still there in the 50's when my family and I were startled to find it. We were afraid it might be lost forever so are glad it finally found a safe resting place on a concrete slab at the museum. I shall greatly appreciate hearing from any reader who can decipher this enigma.

Otto's rock is at the southwest corner of The Historical Museum and Institute of Western Colorado. The main attraction inside is a life-size skeleton of Allosaurus (fig. 23), whose bones are exact plastic replicas of real ones at the museum of Brigham Young University, at Provo, Utah. The painstaking casting of the "bones" and assembly of the self-supporting skeleton was done by Al T. Look, son of author Al Look listed under "References." The museum also houses other items of interest from the Grand Junction area.

Construction of the scenic Rim Rock Drive through the Monument was begun by the National Park Service about 1931 using workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the drive eventually was completed to join roads from Fruita and Grand Junction. The route from Fruita includes a winding road up Fruita Canyon and through two tunnels to the mesa (figs. 3, 44, 45).

A modern Visitor Center, new housing facilities for park personnel, additions to the campgrounds, the Devils Kitchen Picnic Area near the East Entrance, several self-guiding nature trails, and additional overlooks and roadside exhibits were completed in 1964 as part of the Mission 66 program of the National Park Service.

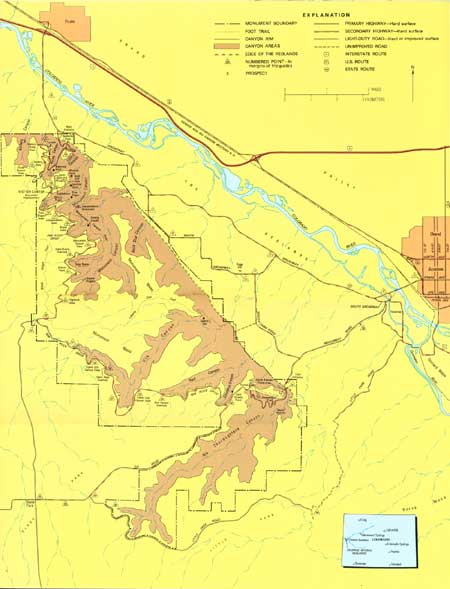

The Monument originally included 13,749 acres, but boundary changes in 1933 and 1939 increased the total to 17,660 acres, and the inclusion of all of No Thoroughfare Canyon and other boundary adjustments in 1978 increased the size to about 20,457 acres, or about 32 square miles (see map, fig. 3).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1508/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 8-Jan-2007