|

Geological Survey Bulletin 611

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part A |

ITINERARY

|

|

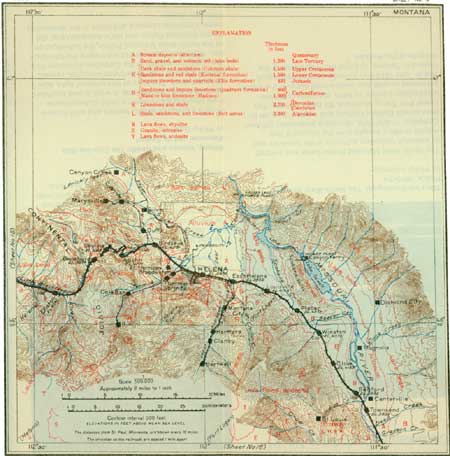

SHEET No. 17. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Townsend. Elevation 3,833 feet. Population 759. St. Paul 1,098 miles. |

The flourishing town of Townsend (see sheet 17, p. 126) is in the heart of a prosperous agricultural region which stretches up and down the river valley for a long distance. A little beyond the town the railway crosses Missouri River and begins to climb to the top of the terrace that faces the river. From this point the traveler may obtain, on the right, a broad view of the fertile farms stretching across the level bottom of the Missouri and broken only by lines of trees through which the stream sweeps down the valley in broad, graceful curves.

On attaining the top of the terrace it is found to be a sloping plain which rises gradually to the foot of the mountain on the west. The train soon passes Bedford siding, from which the old town, established in 1864, can be seen on the right. This was one of the placer camps in the early days, and it is said that the heaps of gravel marking the location of the old workings are still visible.

|

Winston. Elevation 4,375 feet. Population 127.* St. Paul 1,111 miles. |

The train climbs steadily up the sloping surface of the smooth plain and at Winston the traveler can see a wide sweep of the river valley and the Big Belt Mountains on the right. Across the river on the east, at the foot of the mountain, far in the distance, is Confederate Gulch, from the sand and gravel of which more than $10,000,000 in gold has been taken. It is said that in the autumn of 1866 a four-mule team hauled to Fort Benton, for transportation down the river, 2-1/2 tons of gold, worth $1,500,000, nearly all of which had been taken out at Montana Bar and vicinity, near Confederate Gulch.

No hard rocks have been found at the surface near the track, and it is supposed that they are deeply covered by sediment, deposited in the great lake previously described. At the summit between Beaver and Spokane creeks a part of the Belt series can be seen in a knob on the north, but its constituent formations are not distinct enough to be recognized from the train. Charles D. Walcott has described this ridge as a syncline composed of the same rocks (the Belt series) as those that are exposed in Helena on the west and the Big Belt Mountains on the east.

The railway follows in a general way the old stage road along which the gold seekers rushed in 1864-65 to the newly discovered Last Chance Gulch, where the city of Helena now stands, and along this road there may still be seen many old houses that resemble the taverns found along some of the famous old stage roads of the Eastern States.

On the right (north) is the broad valley of the lower part of Prickly Pear Creek, its irrigated and well-tilled fields contrasting with the background of rugged mountains. The gently undulating upland upon which the railroad is built is composed of sand and gravel, which are exposed in every cut. Beneath this surface cover are Tertiary lake beds, as shown by a well a little east of East Helena, which passed through 1,200 feet of soft lake beds before reaching the bedrock.

|

East Helena. Elevation 3,902 feet. Population 1,139.* St. Paul 1,126 miles. |

At East Helena there is a smelter on the left (south), established when this district was a large producer of silver-lead ores, but recently most of the ore smelted here has come from the Coeur d'Alene district in Idaho. The railway on the left is the Great Northern line that runs from Great Falls by way of Helena to Butte. At East Helena the Northern Pacific crosses a number of long-distance electric-power transmission lines which extend from the large power plants at Great Falls, Canyon Ferry, and Hauser Lake, to Helena, Butte, and Anaconda, furnishing light and power not only for municipal purposes but also for the great mining and smelting plants at or near these towns.

|

Helena. Elevation 3,955 feet. Population 12,515. St. Paul 1,131 miles. |

The traveler has now arrived at Helena, the capital of Montana and a division terminal of the railway, and while the engine is being shifted he may be interested in reading a sketch of the early history of the city by Adolph Knopf.1

1Helena is situated in Lewis and Clark County at the eastern foot of the Continental Divide. Its history dates from 1864, when the town sprang into existence as the result of the finding of extraordinarily rich gold-bearing placers where it now stands. At that time Virginia City, on Alder Gulch, 125 miles to the south, was the great center of population in Montana, as the discovery of gold there in almost fabulous quantities in the previous year had drawn many people into the region. In the spring of 1864 reports reached Alder Gulch of a great strike in the Kootenai Valley, and among those who had taken the trail for the new Eldorado was a party of four prospectors under the leadership of John Cowan. They had crossed the Continental Divide west of the site of Helena when they learned from a party of returning prospectors that Kootenai was "played out." They then decided to turn eastward and continue prospecting, but after a season's fruitless effort they proceeded toward Alder Gulch, determined to make one more attempt to discover gold on a small creek at which some indications of precious metal had been obtained on the outward journey. As one of them expressed it, "That little gulch on the Prickly Pear is our last chance"; and the place thus became known to the party as Last Chance Gulch before the actual discovery of its wealth was made. Gold in paying quantities was found here about July 15, 1864.

The news of the discovery spread quickly and the town grew with the rapidity characteristic of placer camps. On October 30 a meeting was held for the purpose of appointing commissioners to lay out a town, as well as to adopt a name for the settlement. During the following winter 115 cabins were erected in the gulch, and within two years the town had a population of 7,500. In 1867 the telegraph had been extended to Helena from Salt Lake City.

Helena, aided by its situation 140 miles from Fort Benton, the head of navigation on the Missouri, soon became the chief mart of commerce in Montana. Virginia City, then the Territorial capital, had already passed its zenith, but it was not until 1874 that the seat of government was permanently removed to its northern rival.

Gold to the value of $16,000,000 was taken from the gravel of Last Chance Gulch, mostly before 1868. In the fall of 1864 gold-bearing quartz veins had been discovered 5 miles south of Helena at the heads of Oro Fino and Grizzly gulches, branches of Last Chance Gulch. The finding of placer and lode gold were thus nearly contemporaneous. The finding of gold in its bedrock source stimulated the quest for the precious metals all over the Territory.

Silver-bearing lead ores in the vicinity of Wickes, Jefferson, and Clancy, 20 miles southeast of Helena, were discovered simultaneously with the finding of the gold placers. The Gregory lode, one of the earliest finds, was located in 1864, and here, in 1867, was built the second smelter established in Montana.

By 1870 the placers had been largely exhausted and a period of stagnation set in, for lode mining could not flourish without adequate and cheap transportation. The great need of the Territory at this time was an adequate system of railway transportation, connecting with the centers of civilization. Freight rates during the first decade were an enormous drain on the resources of the Territory, costing between $1,500,000 and $2,000,000 every year, even after the population had shrunk to 18,000. The chief overland transportation route was Missouri River, by which steamers could reach Fort Benton during high-water stages. But this period of high water lasted from four to six weeks only, and steamers were often forced to stop at the mouth of the Yellowstone, 450 miles distant. On the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad in 1869, much of the traffic was diverted to this route, Corinne, Utah, being the initial point for freight bound for Montana. This, however, involved a haul by teams of 450 miles, and the tolls were oppressive, costing $37.50 for each wagon from Salt Lake to Helena.

In 1883 the Northern Pacific Railway was completed to Helena, and the first train crossed the Continental Divide west of Helena on August 7 of that year. The arrival of the first regular train at Helena on July 4, 1883, was the occasion of a great celebration; but the special feature of the day was the departure of the first "bullion train," carrying 1,000,000 pounds of silver bullion from Montana's mines.

During the later part of 1883 the Helena & Jefferson Railroad was built. This line, which is now a part of the Havre-Butte branch of the Great Northern Railway, connected Helena and Wickes, 20 miles apart. The lead smelter at Wickes was rebuilt and enlarged, so that it was for some years the most extensive reduction plant in Montana and drew ores from a large area, including the Coeur d'Alene district of Idaho. In 1889 it was shut down and dismantled. The same fate has overtaken the many small smelters built in the region tributary to Helena, and at present the only smelter in operation is the East Helena plant of the American Smelting & Refining Co.

The period from 1883 to 1893 comprises the years during which a large output of silver and lead was maintained. The gold obtained from veins during this period came largely from the district at the heads of Ore Fino and Grizzly gulches and from the Marysville district, 17 miles northwest of Helena, which began to come into prominence in 1880. At present mining activity is, on the whole, at a rather low ebb throughout the region tributary to Helena, the annual production fluctuating around $1,000,000. The total yield in gold, silver, lead, and copper aggregates between $150,000,000 and $200,000,000.

Helena lies on the south side of a great dome-shaped uplift, whose center is somewhere north of the Scratch Gravel Hills, which can be seen on the right (north) from Helena. The rocks dip away from the center of this uplift, but there are many minor folds or wrinkles on the flanks of the dome that in places even produce dips in the opposite direction. About Helena the general dip is toward the south, whereas at Mullan Pass it is toward the southwest. The rocks about Helena are broken by a number of faults, which in general ray out like the spokes of a wheel from the center of the uplift. The rocks here are much like those exposed about Threeforks, but they have been intruded in many places by masses of igneous rock that have come up from below, and they have been altered by the heat and pressure thus developed.

On leaving Helena the traveler has a good view of the setting of the city at the mouth of Last Chance Gulch, with the prominent peak Mount Helena on the west. About 2-1/2 miles out the railway crosses the Great Northern line to Great Falls and Havre, and near this crossing the Red Mountain branch of the Northern Pacific turns to the south to a mining district up the valley of Tenmile Creek. Beyond milepost 3 Fort Harrison, the largest military post in the State, is seen on the left (south).

Just west of Helena begins the long grade to the summit of Mullan Pass. The ascent, 1,618 feet, is accomplished in about 20 miles.

|

Birdseye. Elevation, 4,231 feet. St. Paul 1,139 miles. |

From Clough Junction, just beyond Birdseye, a branch line leads northward to Marysville,1 one of the most productive mining camps in this vicinity, situated just below the crest of the Continental Divide, about 17 miles northwest of Helena.

1The prosperity of the Marysville mining camp has hinged largely on the fortunes of the Drumlummon mine, the oldest, most steadily operated, and most productive property of the district. The Drumlummon lode was discovered in 1876 by Thomas Cruse, who had been working some placers along Silver Creek below the present site of Marysville and the mine was gradually developed by him until 1880, when a 5-stamp mill was erected. In 1882 the property was sold to an English company known as the Montana Mining Co. (Ltd.) for $1,500,000. During the operations of this company $46,000,000 worth of gold and silver was extracted. In the early nineties the property became involved in protracted litigation, and in recent years the mine has been worked only intermittently. In 1911 the property was sold to the St. Louis Mining & Milling Co., which commenced to rehabilitate the milling plant, to operate the old workings, then badly caved, and to search for new ore bodies.

Other notable mines in the district are the Belmont, Cruse, Penobscot, Bald Butte, Empire, and Piegan-Gloster. The district has produced about $30,000,000.

The presence of ore at Marysville is due to a small mass of granite that has been forced up from below though the limestone and shale of the Belt series. Some of the ore was probably deposited soon after the intrusion, but the richest veins are supposed to have been formed at a later date. The sedimentary rocks around the granite have been so thoroughly baked that they are changed into hard flinty rocks known as hornstone. The ore occurs along the contact of the granite and the hornstone.

The rocks in the Front Range in the vicinity of Mullan Pass lie on the southwest flank of the great dome whose center is north of the Scratch Gravel Hills. The regular southwestward dip of the rocks away from the center of this dome is interrupted by a small syncline (a downward fold of the rocks) which lies west of the summit and also by many intrusions of igneous rock, some of which are of great extent, whereas others are small and have had little effect upon the general structure. As the rocks on the east side of the summit dip toward the range, the westbound traveler passes over the several formations in ascending order.

The rocks are poorly exposed about Birdseye and Clough Junction, and the traveler will have difficulty in identifying the Belt series and the Cambrian and Devonian formations. Near milepost 11 the massive light-colored Madison limestone (Carboniferous) will attract attention on account of its many exposures on the hill slopes. West of the limestone is an intrusive mass of granite (quartz monzonite), which is very extensive, being the same as that which constitutes the mountains about Boulder and the summit over which the Northern Pacific passes east of Butte. It is noteworthy on account of the peculiar way in which it weathers. Some parts seem to be harder than others and less subject to the action of the weather, and these parts stand up as towers and pinnacles. The projecting crags are particularly numerous and fantastic in the vicinity of Austin.

|

Austin. Elevation 4,771 feet. St. Paul 1,144 miles. Blossburg. Elevation 5,573 feet. St. Paul 1,151 miles. |

The railway engineers, in order to obtain a regular grade to the summit, found it necessary to make large loops, and the open country about Austin gave them the opportunity they desired. Just east of the station two stretches of track, one above the other, are visible on the right. The steepness of the grade may be appreciated by listening to the laboring of the engine or by looking back after making the sharp turn above Austin. The track here runs along the contact of the limestone and the granite, and such localities are generally favorable for the deposition of ores. Many prospect pits have been sunk in search of the precious metals, but apparently without success. Above the great loops near Austin the track winds in and out, up the ravines and around the spurs, steadily climbing on the Madison limestone until it arrives at the east end of the Mullan tunnel. Originally the road was carried over the summit, but on the completion of the tunnel the high line was abandoned. The upgrade continues through the tunnel, which is 3,875 feet long, and reaches the highest point at Blossburg, at the far end. The tunnel was constructed entirely in the granite, although the limestone extends to the eastern portal and the sandstone and shale of the Cretaceous appear only a short distance west of the other portal.

The traveler has now crossed the backbone of the continent, and as he starts down the Pacific slope and looks back at the summit he is probably surprised at the smoothness of the tops and the absence of the rugged features which most people have, in their minds, associated with Mullan Pass1 and the Continental Divide.

1The first authentic account of a trip through Mullan Pass is that contained in the report of the Government engineers who, in 1853, conducted systematic explorations in order to find the best route for a Pacific railroad. This expedition, under the command of Gov. Isaac I. Stevens, of Washington Territory, established field headquarters at the old mission of St. Mary (now Stevensville), in the Bitterroot Valley south of Missoula. From this camp engineers explored the passes through the mountains and reported on their feasibility for railroad construction.

The two men connected with this work who are best known to the public were Capt. George B. McClellan, who had charge of surveys on the Pacific coast and who afterward came into prominence in the Civil War, and Lieut. John Mullan, who was in charge of an exploring party in the Rocky Mountains and who later achieved local distinction through the building of a military road from Fort Benton to Walla Walla. (See p. 131.)

Late in the summer of 1853 Lieut. Mullan made a scouting expedition to Fort Benton and from that place to Musselshell River by way of the Judith Basin. He tried to induce some Indians to guide him through a low pass that had been reported west of the place where Helena now stands, but the Indians were on a hunting trip for their winter supply of meat and could not be induced to join him. Failing in this, he ascended the Musselshell and crossed the Big Belt Mountains to the site of Helena. He crossed the summit west of this place on September 24, 1853, with little difficulty, through what is now known as Mullan Pass. Twenty years later the same route was followed by the locating engineers of the Northern Pacific and the original line was built across the summit at this place.

West of the summit the rock is not well exposed, partly for the reason that it is shale (Cretaceous) which is not hard enough to form ridges or knobs. This shale is the youngest rock crossed by the railway in this vicinity. It lies in the middle of the great syncline previously referred to and constitutes the core of the fold. West of this place the rocks should be crossed in reverse order, but they are so badly faulted and cut by intrusive masses that it is very difficult to determine the structure. The most prominent rock on this side of the fold is the Madison limestone which is quarried at Calcium, between mileposts 26 and 27, and burned into lime.

West of Calcium the rocks are badly broken by faults so that it is almost impossible to identify the various formations from the moving train, but near milepost 28 there is a prominent ledge of quartzite (Quadrant) on the right (north) which carries at its top a valuable bed of rock phosphate. Analysis shows this rock to contain from 40 to 60 per cent of phosphate of lime. This material is valuable as a fertilizer, and the United States Geological Survey has been actively engaged in the last few years in mapping deposits of such rock. It is described by R. W. Stone below.1

1The bed of phosphate rock just east of Elliston is over 5 feet thick and carries 61.6 per cent of tricalcic phosphate. Detailed examination has shown that within 8 miles of Elliston, on the north of the railway, there is available within easy mining depth approximately 86,000,000 tons of rock phosphate, or an equivalent of 5,440 acres underlain by a bed 4 feet thick. The phosphate is in a definite layer and is interbedded with other rocks, as coal is. At Elliston the phosphate bed is nearer the railway than elsewhere in western Montana. Phosphate is found in the same formation in the hills 5 miles north of Garrison; near Phillipsburg, a town at the end of the branch south of Drummond; at Lime Spur; and at Melrose, 30 miles south of Butte.

When rock phosphate was discovered in the Rocky Mountains a number of years ago, the United States Geological Survey undertook the determination of the geographic extent and quantity of available material. It has been found that rock phosphate occurs in the mountains of Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah, in quantities so stupendous that when expressed in tons the amount is almost inconceivable. The estimated total in the areas examined in the years 1909-1913 is approximately 7,777,000,000 long tons, or triple the quantity of anthracite mined in Pennsylvania in the last century. When all the known deposits in these four States have been examined in detail, the estimated available tonnage will considerably exceed these figures.

The most noteworthy characteristic of western rock phosphate is its oolitic texture. (Oolite, from the Greek, meaning egg stone, is applied to certain limestones whose texture suggests the roe of a fish.) The rock is composed of rounded grains ranging in size from the tiniest specks to bodies half an inch or more in diameter. The freshly mined rock usually has a dark-brown or black color, but the weathered material found along the outcrop is a light or dark gray with a whitish to bluish coating that has a tendency to concentrate in a netlike pattern. Rock phosphate is appreciably heavier than ordinary limestone, and some varieties give off a fetid odor when struck with a hammer.

On account of the high cost of transportation the present market of the western phosphates is confined to the Pacific coast States. In 1914 the western phosphate field furnished 5,030 tons, valued at $15,488, or an average price of $3.08 a ton. This is about one-fifth of 1 per cent of the total phosphate production of the United States, which in 1914 amounted to 2,734,043 long tons, valued at $9,608,041.

Phosphate rock is converted into more soluble phosphates for use in the manufacture of fertilizers by treatment with sulphuric acid. As this acid can be made from smelter fumes which ordinarily go to waste, the proximity of phosphate deposits to the great smelting centers of the West is likely to prove beneficial not only to the miners of phosphate but also to the smelter men and the farmers.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/611/sec18.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006