|

Geological Survey Bulletin 611

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part A |

ITINERARY

|

|

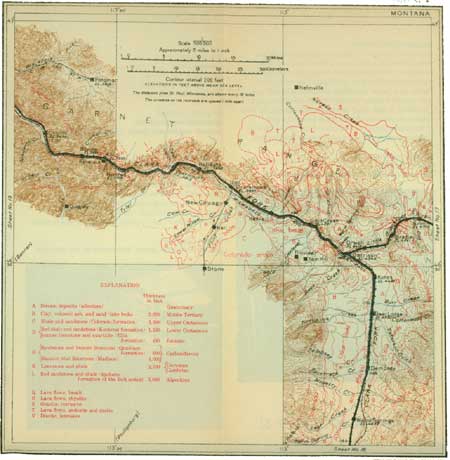

SHEET No. 18. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Elliston. Elevation 5,061 feet. St. Paul 1,160 miles. Avon. Elevation 4,702 feet. St. Paul 1,169 miles. |

At Elliston the red shale of the Kootenai (Lower Cretaceous), followed by the dark shale of the Colorado, is visible on both sides of the valley. A short distance below the town there is a large area of dark-red lava (rhyolite) which extends as far as milepost 35. From this point westward for some distance the valley is much broader than it is near Elliston, and at some stage of the Tertiary period contained a lake. The sediment deposited in this lake can be seen on the right (north) along the track as far as Avon (see sheet 18, p. 134), except where a sharp ridge of rhyolite east of the town extends from the right and just crosses the railway track. Beyond Avon Little Blackfoot River enters a rugged canyon, at first in red rhyolite and then in thin-bedded red sandstone of the Belt series (Algonkian). These rocks continue a short distance beyond milepost 41 and are separated from the Cretaceous rocks to the west by a small mass of igneous rock (andesite) that has been intruded along the fault.

The lowest formation of the Cretaceous and the first to be seen in traveling westward is the Kootenai, which is visible on the left. This formation, characterized by bands of bright-red shale, is only a few hundred feet thick and is overlain by Upper Cretaceous rocks which extend continuously from this place to Garrison. This overlying formation is undoubtedly the same as the Colorado shale farther east, but its composition is different. In the eastern localities it is mostly a dark shale with only here and there a bed of thin sandstone, but along the Little Blackfoot it is composed of a succession of beds of sandstone and shale with sandstone predominating.

The Cretaceous beds dip gently in various directions, but in general they lie nearly flat and constitute the bottom of a great sag or syncline 15 to 20 miles wide. Although this syncline is flat and broad, it has been subjected to much minor folding or wrinkling, which locally has tilted the beds or even broken them, where the pressure has been more severe.

|

Garrison. Elevation 4,344 feet St. Paul 1,182 miles. |

The Cretaceous rocks are much softer than the older rocks, and weathering has reduced them to low hills and rounded slopes that are a marked feature of the topography in the vicinity of Garrison. At this village the old main line is joined by the more recent line through Butte.

LINE WEST OF GARRISON.

The famous Deer Lodge Valley, which is so conspicuous on the Butte line, continues west of Garrison as far as Drummond, but for some distance it is not apparent from the train. When viewed from some commanding eminence the valley is distinctly outlined, but when seen from the river level the immediate bluffs conceal and obscure the background, so that the traveler will probably fail to recognize the broader, more open valley in the bottom of which the stream has cut its present channel. The broad valley is underlain by soft Cretaceous rocks similar to those which border it on both lines above their junction at Garrison. As explained on page 115, the bottom of the valley bulged up north of the place where Garrison is now located. Clark Fork had already established a meandering course on the sediments filling the old lake basin, and when the bulge occurred the stream simply persisted in its old course, cutting deeply into the underlying harder rocks and preserving all its former sinuosities. The railway can not follow the swings of the stream, because they are too short, so it strikes straight through, tunneling wherever necessary. The St. Paul road lies near the Northern Pacific on the left.

Halfway between mileposts 53 and 54 there is a sign on the left which calls attention to the fact that here on September 8, 1883, was driven the last spike that established the connection between the eastern and the western ends of the Northern Pacific Railway. The event was celebrated in an elaborate manner, and prominent people, including William M. Evarts (as orator), Henry M. Teller, Secretary of the Interior, and Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, were present. The completion of the Union Pacific Railroad, in 1869, had been celebrated by similar ceremonies at Promontory, west of Ogden, Utah, and the gathering in Montana marked the completion of the second great transcontinental line. Since that time other roads have been constructed across the continent without creating any marked attention, but these two roads were the pioneers and the completion of each was an event of nation-wide importance.

The rocks north of Garrison are mostly of Cretaceous age and correspond to the Colorado shale, which is exposed in the bluff south of Billings. At Billings the formation consists of dark shale containing many marine fossils, but about Garrison it is composed largely of sandstone, conglomerate, and tuff, and no marine fossils have been found in it. The kind of material composing the formation and the character of the fossils indicate shore conditions and fresh or brackish water, instead of the salt water that prevailed farther east. North of Garrison the Cretaceous rocks are cut by igneous rocks that have been forced up through them in great masses and in narrow dikes. The most prominent igneous mass that can be seen from the train is one that crosses the track at milepost 56. This rock has been quarried for material with which to riprap the slopes of the roadbed where it is washed by the stream. At milepost 57 there is a high, rocky wall on the left composed of sandstone in which there is the standing stump of a tree. It is now silicified but remains as a mute record of a time, long ago, when this country, now so barren of timber, was covered with trees several feet in diameter. About halfway between mileposts 57 and 58 is the mouth of Gold Creek, the creek upon which gold was first discovered in Montana.1 The placers are at Pioneer, 5 miles up the creek, and it is reported that at least $12,000,000 has been taken from them. They are still producing in a small way. Cretaceous rocks form the surface here, but they are generally soft and give rise to low hills and gently rounded slopes.

1It is reported that gold was first discovered in Montana in 1852 by a half-breed named François, but better known to his associates as Benetsee. On his return from the gold fields of California Benetsee began prospecting on what is now known as Gold Creek, in Powell County. He found some gold, but did not obtain enough to pay for operations.

The finding of gold at this locality soon became known among the few mountaineers in the country, and in 1856 a party on their way from the Bitterroot Valley, where they had spent the winter trading with the Indians, visited Gold Creek and found more gold than Benetsee had been able to obtain, but not enough to induce them to remain.

Desultory prospecting was done in the years following the visit of this party, but without any definite result until 1862, when rich pay gravel was discovered. Soon after this the extraordinarily rich placers of Alder Gulch, at Virginia City (1863), and Last Chance Gulch, at Helena (1864), were discovered, and these so far overshadowed the deposit on Gold Creek that it was almost forgotten.

|

Gold Creek. Elevation 4,201 feet. Population 730.* St. Paul 1,187 miles. |

At the station of Gold Creek the valley floor merges into the rolling upland that stretches far northeastward to the foot of the Garnet Range, which is composed of Paleozoic limestones and quartzites. At milepost 61 the valley widens, and 2 miles farther west the harder rocks disappear and the valley floor and the slopes are composed solely of the lake beds, which mantle all the older formations. The lake beds continue to milepost 68, where the Cretaceous rock is again visible on the north.

|

Drummond. Elevation 3,967 feet. Population 383.* St. Paul 1,200 miles. |

Drummond lies at the intersection of two very broad, flat valleys, one along the main line of the Northern Pacific and the other leading off to the southwest along a branch line running to the mining district of Phillipsburg. These valleys are filled with lake sediments, which show that a great lake existed here in Tertiary time.

In the region above Drummond the rocks form a great flat syncline, with the Cretaceous occupying a wide area in the middle. In this central region the rocks were only slightly disturbed, but near Drummond, on the margin of the basin, the rocks are thrown into great folds which carry the limestone and quartzite beds of the Carboniferous and Devonian high into the mountain tops. In fact the Garnet Range consists of a series of such folds, trending in a northwesterly direction, which become more and more complicated toward the northwest. Clark Fork cuts into the foothills of the range west of Drummond, and the great folds can be seen and studied from the moving train.

From Drummond the railway follows closely the axial line of a large syncline for a distance of about 7 miles. The youngest rocks exposed in this trough are the bright-red and maroon shale and sandstone of the Kootenai. The rim of the syncline is formed of the Madison limestone, which 3 miles west of Drummond forms conspicuous cliffs on the south and can be seen on the north in the tops of the high wooded hills about 2 miles distant from the track.

To a point about 3 miles below Drummond the valley is still called the Deer Lodge Valley, but at that point the walls close in, especially on the left, and thence down to Missoula it is known as Hell Gate Canyon. It is probable that this name originated in the vicinity of Missoula, but it is now applied to the whole of the canyon.

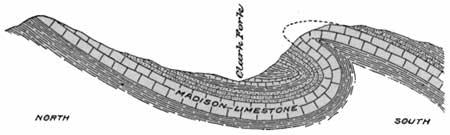

At the entrance to the canyon, near milepost 74, the Madison limestone caps the high hill on the south and makes a picturesque setting for the stream and valley at its foot. This cliff can best be seen from a point near milepost 75 late in the afternoon, when the slanting rays of the sun bring out every detail of the towers and pinnacles of the rugged cliff. The limestone appears to lie horizontal, just as it was laid down on the bed of the ocean, but when studied carefully it is found to be turned completely over, as shown in figure 28. The overturning of the side of the syncline was probably produced by a strong thrust from the southwest which not only caused the rocks to fold in the form of a trough, but continued and pushed the rocks composing the side of the fold far toward the middle of the basin.

|

| FIGURE 28.—Diagram of fold west of Drummond, Mont. Clark Fork flows near the middle of a great basin, and the Madison limestone is folded back upon itself in the hill on the south. |

Below the cliff of limestone the stream is very tortuous, winding from side to side of the synclinal basin in which it is flowing. The railway originally followed all the crooks and bends of the stream, but now it pursues nearly a straight course, cutting through the points and bridging the stream, or diverting its course where diversion could be accomplished readily. The deep cuts across the projecting points in the bends of the stream afford an excellent opportunity to see the dark-red shale of the Kootenai formation, which is exposed in the middle of the trough.

At milepost 79 the river, accompanied by the railway, turns to the southwest and cuts across the rim of the syncline, which is made up of hard, massive limestones and quartzites (Carboniferous). As these rocks always make rugged and picturesque canyon walls, it is well for the traveler who wishes to obtain a good view to be ready, as it takes only a minute or two to pass through the interesting part of the gorge. Just below milepost 79 the railway crosses the Quadrant quartzite, which makes little showing on the hill slopes. This is soon passed, and then the massive layers of the Madison come into view. As the course of the road changes more toward the northwest, the limestone beds can be seen rising in great cliffs on the left, but beyond another bend to the west they appear in all their ruggedness in the wall on the right. The limestone, stained red or rather splotched with red, rises on both sides to a height of 500 or 600 feet; and the rock is carved into the most fantastic shapes, such as pillars, needles, towers, and minarets—in fact almost every form the imagination can conceive. The combination of rugged forms and striking colors gives to this canyon a character of its own that would be hard to duplicate in any other region. The limestone on the southwest rests against a mass of lava (andesite), which covers much of the country southwest of the river and is exposed in its bluffs in the vicinity of the next station, Bearmouth.

|

Bearmouth. Elevation 3,813 feet. Population 161.* St. Paul 1,210 miles. |

Opposite Bearmouth a small stream, Bear Gulch, enters the river from the right. Here gold-bearing gravel was discovered in October, 1865, by a party under the leadership of Jack Reynolds. In the two years following its discovery it produced $1,000,000, and later the yield was increased to many times that amount. The placers are no longer worked, but it is said that gold-bearing quartz veins have been found which may some day bring new activity to this region.

West of Bearmouth the lava forms the walls of the canyon for a distance of 2 miles to the mouth of Harvey Creek, a small stream entering the river from the south. Opposite and a little below the mouth of this creek there is a syncline extending to the northwest. The rocks in the middle of this basin are the red shale and sandstone of the Kootenai, rimmed about by lower and older formations, the lowermost of which are the limestones and quartzites of the Carboniferous.

About Blakeley siding and for several miles west of it the rocks on both sides of the canyon are red shale or argillite and red sandstone belonging to the Spokane shale (Algonkian). This is the first appearance in the westward journey down Clark Fork of this red argillite, which makes most of the walls of Hell Gate Canyon from Blakeley siding to Missoula.

Blakeley siding is well within Hell Gate Canyon, the principal highway by which the white man in the early days and the Indian before him crossed this mountainous region. The first permanent wagon road in this part of the country was built in this canyon in 1859-1862, and is known from its builder as the Mullan road. Its construction is intimately associated with the early development of the country, and a more extended account is given below.1

1Hell Gate Canyon is one of the great natural thoroughfares of the continent. Though this canyon the Flatheads and other tribes of the West journeyed to the plains annually to hunt the buffalo, and though its winding trails crept the stealthy Blackfeet on their numerous forays against their more peaceful neighbors on the west.

In 1853, when the Government engineers were exploring the various passes of the Rocky Mountains to find the most feasible route for a Pacific railroad, they also planned for a military road which should connect Fort Benton, then the head of navigation on the Missouri and the most prominent post on the east side of the mountains, with Fort Walla Walla, which was of equal prominence on the Pacific slope. Lieut. John Mullan was the most ardent advocate of a military road, but he was ably seconded by Gov. Stevens, the leader of the expedition.

The location of such a road east of the Bitterroot Valley (Missoula) was easily determined, but the country west of that valley afforded the greatest obstacles, so in 1854 Mullan explored three possible routes across the Coeur d'Alene Mountains in order to determine the best location. These were (1) Clark Fork, Lake Pend Oreille, and Spokane (the town of Spokane was not then in existence); (2) the St. Regis and Coeur d'Alene valleys; and (3) the Lolo trail.

Lewis and Clark had already passed over the Lolo trail and had given so graphic a picture of its difficulties that it was not very seriously considered by Mullan, who devoted most of his energies to the other two routes. The route first mentioned, along which the Northern Pacific Railway was subsequently built, was partly explored by Mullan in 1854, but unfortunately the attempt was made in May, when the snow in the mountains was melting rapidly, and he had great difficulty in crossing the streams. He persisted, however, on his course down Clark Fork until he reached Lake Pend Oreille (pronounced locally pon-do-ray), but here he found it practically impassable on account of high water, so he reluctantly gave up this route as impracticable. Mullan then explored the St. Regis and Coeur d'Alene valleys and decided that these afforded the best route. In selecting the Coeur d'Alene route he was influenced by its directness and by the fact that the summit is not especially rugged nor difficult of access, but he failed to realize the severity of the winters on this exposed mountain pass. That in later years he regretted this choice is shown by the following statement: "I have always exceedingly regretted that it was my fortune to examine this route [Clark Fork] at so unfavorable a period, for I have been convinced by later data that it possessed an importance, both as regards climate and railroad facilities, enjoyed by no other line in the Rocky Mountains between latitudes 43° and 49°." The building of the Northern Pacific Railway down Clark Fork seemed to justify his conclusion, but it must be remembered that at a later date this same company built a branch road over almost the exact route selected by Mullan up St. Regis River, and that only a few years ago the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway Co. built its main line along nearly the same route. This all goes to show that railway building since the days of Lieut. Mullan, or even since the building of the Northern Pacific main line, has changed, and that now directness of line may be the controlling condition, and the crossing of mountain ranges a mere incident.

Although explorations for a military road were made and a route selected in 1854, actual construction was delayed several years. Mullan was on the ground ready to begin work in that year, under general orders from the War Department, but trouble with the Indians throughout eastern Oregon and Washington prevented, and he passed another year without accomplishing any work on his favorite project.

In March, 1859, Congress appropriated $100,000 for the construction of the road, and work was begun by Mullan at Walla Walla on June 28 of the same year. The road extended northeastward from Walla Walla to the Coeur d"Alene Valley. The first year the road was cleared, so as to be passable by wagon, from Walla Walla to the headwaters of the St. Regis. The next spring Mullan began work where it was stopped the previous autumn and pushed the construction up Clark Fork to Missoula and then up Hell Gate Canyon as far as Garrison. From this point it followed Little Blackfoot River along the original line of the Northern Pacific to Mullan Pass, down on the east side to the vicinity of Helena, and thence north to Fort Benton. By the end of the season the party reached the eastern terminus, but it is needless to say that this great stretch of road was little more than a trail, and much work was needed before it was really passable.

The summers of 1861 and 1862 were spent by Mullan in going back over the line building bridges, making cuts where the canyons were narrow, and relocating the road about Coeur d'Alene Lake, where the ground proved to be soft and marshy.

The road thus built had a length of 624 miles through the roughest part of the Rocky Mountains and cost $230,000. It was never used to any extent for military purposes and soon fell into decay, except where it was kept up by the local authorities. About 20 years later it was supplanted by the Northern Pacific Railway.

Beyond Blakeley siding the canyon walls are composed of the Spokane shale (Algonkian), and its dark-red color is visible at many places. It is well exposed in a cut by the side of the road, at milepost 87, in a projecting point known as Medicine Tree Hill.

Some Paleozoic limestone and quartzite are to be observed on the right (north) at intervals for the next 5 or 6 miles, and then the walls of the canyon are made up almost entirely of the red Spokane shale. The Algonkian rocks are supposed to be the oldest sedimentary rocks exposed in the Rocky Mountain region. Very few fossils occur in them, but those that have been found are fresh-water forms, indicating that the sediment forming the rocks was deposited in a lake or lakes.

Many of the beds of sandstone are beautifully ripple marked, showing that the water in which the sand was deposited was so shallow that the waves piled up the sand in ripples or ridges. They also show cracks, indicating that at times the water receded, allowing the material composing the bottom of the lake to dry and crack irregularly, as mud deposited along a stream to-day will crack when it dries. Another indication of shallow water, or of no water at all, is the preservation of the prints of raindrops, which, after the millions of years that have elapsed since these rocks were mud on the shore of some lake, indicate the direction from which the storm came that drove along the coast. This may not be of great importance, but it illustrates how well nature has preserved the record of events of that far-off time, if only we will learn to interpret it.

|

Bonita. Elevation 3,594 feet. St. Paul 1,224 miles. |

The Spokane shale is well exposed in the portals of the tunnel between mileposts 94 and 95 and can be seen to good advantage from the observation car. From Bonita to Missoula the walls of the canyon are steep and high but not particularly rugged. They are composed almost entirely of the Spokane shale, which supports a much heavier growth of pine trees than the other formations. This is particularly noticeable on the south side of the canyon, or on the northward facing walls. The difference in the vegetation on the two sides is due to the difference in the amount of moisture conserved. The northward facing slope is not exposed to the direct rays of the sun, and hence the moisture in the soil is not readily evaporated and trees thrive better than they do on the opposite side.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/611/sec19.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006