|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

|

|

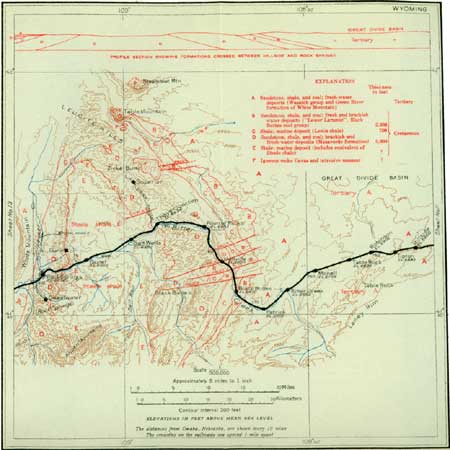

SHEET No. 12. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

West of Red Desert station is Hillside.

|

Tipton. Elevation 6,993 feet. Omaha 747 miles. |

To the left (south), about 4 miles south of Tipton station is a prominent escarpment known as Laney Rim, formed by the beds of the upper part of the Wasatch group. To the right is an upper part of the Wasatch group. To the right is an uninterrupted view of the Green Mountains, more than 50 miles away. In the distance toward the northwest may also be seen the Leucite Hills. Toward the west is a conspicuous dark-colored knob called Black Butte, which has served as a prominent landmark since the days of the earliest pioneers.

The stratified rocks, which are nearly horizontal in the center of Great Divide Basin, have here a gentle inclination toward the east. The softer layers have been eroded away faster than the harder ones, which now appear as prominent shelves. Near Tipton (see sheet 12, p. 70) the train crosses one of the harder layers of the Wasatch beds, a shell-making sandstone, which may be seen to the left, south of the railroad, rising higher and higher toward the west until, on Table Rock (see Pl. XIV, A), south of Table Rock station, it is about 800 feet above the level of the track. These rocks near Tipton contain great numbers of shells of fresh-water mollusks and some fossil bones.

|

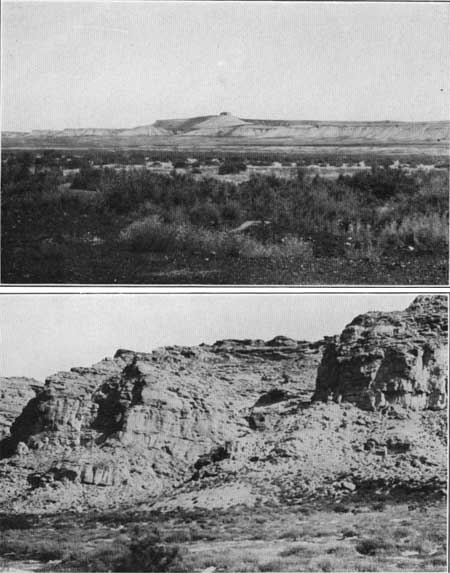

| PLATE XIV.—A (top), TABLE ROCK NEAR BITTER CREEK, WYO. This rock is composed of alternating hard and soft Tertiary beds. The beds from the top of the table and of the benches. B (bottom), CHARACTERISTIC VIEW OF THE NORTH WALL OF THE CANYON THROUGH WHICH THE TOURIST PASSES NEAR POINT OF ROCKS, WYO. The bluffs are composed of the coarse sandstone which separates the two groups of coal beds of the Mesaverde formation. The Rock Springs coal group lies below this sandstone and the Almond coal group above it. |

|

Bitter Creek. Elevation 6,692 feet. Omaha 764 miles. |

Toward the east from Bitter Creek station may be obtained a good view of Table Rock, a prominent point in the eastward-sloping shelf just mentioned. The low hills south of the station are covered with gravel deposited by Bitter Creek before that stream had eroded to its present depth. The gravels contain many agate pebbles, some of them beautifully colored. A well drilled at this station years ago to a depth of 1,300 feet found water under sufficient pressure to flow at the surface, but too alkaline to be of much use.

West of Bitter Creek station the railroad crosses the eroded edges of eastward-dipping strata that range in age from middle Eocene to Cretaceous. At Patrick siding these strata have the same general appearance as the Wasatch beds farther east, but west of this siding the hard layers are closer together and outcrop in numerous ridges. These ridges are parts of the east limb of the Rock Springs dome.1

1The Cretaceous rocks that are covered by the Tertiary beds of the Great Divide Basin on the east and those of the Bridger Basin on the west are exposed between Black Buttes and Rock Springs because they have been arched up into a great dome from the top of which the younger beds have been removed by erosion. The major axis of this dome is about 90 miles long and trends nearly north and south close to the west limb of the dome. The beds on the west dip 15° to 30°; those on the east dip 5° to 10°. The minor axis is about 40 miles long and passes through the dome south of Rock Springs. The oldest rocks exposed are the shales near Baxter siding, which correspond to the Steele shale seen farther east. Around this shaly center outcrop in concentric zones (1) a series of non coal-bearing sandstones; (2) the Rock Springs coal group, 600 to 2,400 feet thick, of lower Mesaverde age; (3) a massive sandstone, 800 feet thick, of middle Mesaverde age; (4) the Almond coal group, 900 feet thick, said to be of upper Mesaverde age; (5) the Lewis shale, 750± feet thick; (6) the Black Buttes coal group; and (7) the Black Rock coal group, of Tertiary age. It has been estimated that the amount of coal in the Rock Springs field available for mining—that is, within 3,000 feet of the surface and in beds 2-1/2 feet or more in thickness—exceeds 142,000,000,000 tons. As coal is fossilized vegetal matter, the traveler, as he views the barren hillsides where now scarcely a living thing can be seen, may well wonder how all this great store of carbonaceous matter came there. These coal beds are mute but forceful reminders that desert conditions have not always prevailed in this region. Fossil plants, such as palms, figs, and magnolias, found at many places in these coal beds prove that the carbonaceous matter of the coal accumulated in swamps at a time when the climate was as mild as that of Florida at present.

|

Black Buttes. Elevation 6,610 feet. Omaha 773 miles. |

Just before reaching Black Buttes station the train crosses the youngest of the three groups of Cretaceous coal beds that are exposed around the Rock Springs dome. This is called the Black Buttes coal group. The coal of the Black Buttes group has been mined to some extent. An abandoned mine may be seen to the right (north) of the railroad half a mile east of Black Buttes station, where also a spur runs to an active mine a mile farther south.

|

Hallville. Elevation 6,554 feet. Omaha 778 miles. |

West of Black Buttes the route follows a valley eroded mainly in the Lewis (Upper Cretaceous) shale. The rocks have been displaced by faulting here, so that individual beds are not easily traceable by one passing rapidly over them. At Hallville siding the road crosses one of the faults or displacements of the strata that are so numerous in this region and enters a narrow canyon whose steep, craggy walls display the hard rocks of the upper part of the Mesaverde formation. From this siding is obtained a good view of the Almond coal group,1 which crops out north of the railroad (to the right) and is underlain by the white sandstone of the middle part of the Mesaverde.

1 The coals of the Almond coal group are of poorer quality than those of the Rock Springs coal group and as they occur close to the abundant supply of high grade coal mined at Rock Springs they have not been much exploited. The only place where they have been mined is Point of Rocks, formerly called Almond.

|

Point of Rocks. Elevation 6,503 feet. Omaha 784 miles. |

The light-colored sandstone near the middle of the Mesaverde formation makes prominent cliffs at the town of Point of Rocks. (See Pl. XIV, B.) It is an important water-bearing sandstone and yields mineral waters. This sandstone is slightly conglomeratic, is irregular in texture and hardness, and has been eroded into many fantastic and curious forms. To some of the cavernous hollows in it have been given names, such as "Hermit's Grotto," "Cave of the Sands," and "Sancho's Bower." Three wells that have been drilled here to depths of a little more than 1,000 feet have obtained an abundant supply of water. The water is strongly charged with sulphureted hydrogen (H2S), which soon escapes or is oxidized on exposure to the air. From Rawlins to Green River, a distance of 134 miles, there is scarcely a place where water fit to drink can be found at the surface. The springs and The streams are alkaline, and water from the wells at Point of Rocks is hauled for domestic and railroad use over much of this distance.

The coal beds of the Almond group are conspicuously exposed above the conglomeratic sandstone, and certain fossil oysters and other brackish-water shells are abundant in the rocks above the coal. The coal was mined about a mile east of the town, where the dip of the strata brings the coal beds to the level of the valley floor.

About 2 miles west of Point of Rocks the route leaves the massive cliff-making sandstone and comes to the relatively soft yellow sandstone and shale of the Rock Springs coal group,1 which contains the principal coal beds of this region.

1The Rock Springs group of coal beds is of lower Mesaverde (middle Upper Cretaceous) age and is the most important group of coals in Wyoming, for it contains many beds of bituminous coal of higher grade than that of the other groups of this region. The basal portion of the group of rocks consists of heavy ridge-making coal-bearing sandstones (Pl. XV, A, p. 67), and the remainder of brown, yellow, and white sandstones, shale, clay, and interbedded coal. The group is about 2,400 feet thick and contains at least twelve coal beds that range from 2 to 10 feet in thickness and many other beds less than 2 feet thick. These beds are somewhat regularly distributed through the group and are fairly persistent along the strike. They have been prospected from Sweetwater, south of Rock Springs, northward around the end of the dome to Superior. Very little prospecting has been done south of Superior, as in this locality the coal beds are somewhat thinner and are fewer in number than between Superior and Rock Springs.

|

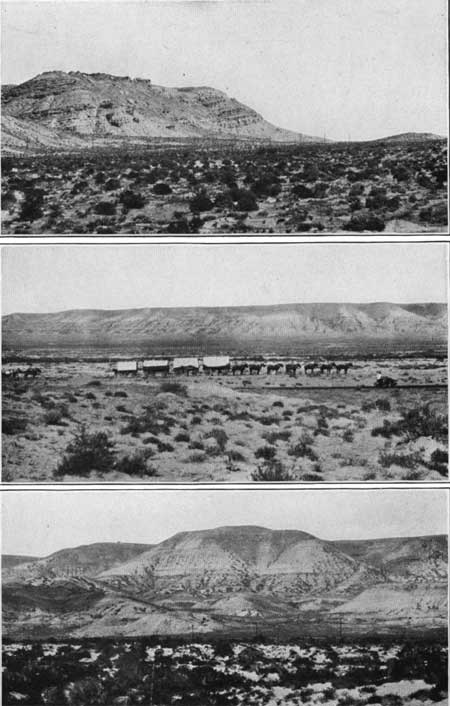

| PLATE XV.—A (top), COAL-BEARING SANDSTONE OF MESAVERDER FORMATION IN THE WESTERN PART OF THE ROCK SPRINGS DOME EAST OF ROCK SPRINGS, WYO. B (middle), TRANSPORTATION, OLD AND NEW. A 14-horse team hauling freight from the railroad (in the foreground). The bluff in the distance is White Mountain and is composed of Tertiary beds. C (bottom), NEAR VIEW OF WHITE MOUNTAIN. White Mountain consists of pink sandstone and shale of the Wasatch group below and the light-green beds of the Green River formation above. |

Just east of Thayer Junction the railroad crosses the massive sandstones that occur near the base of the Mesaverde formation and emerges into an open space occupied by the marine shale which farther east is called the Steele shale. This is separated from the younger massive sandstones of the Mesaverde formation by a thick zone of shaly yellow sandstone that forms prominent benches and "badland" slopes.

|

Thayer Junction. Elevation 6,434 feet. Omaha 791 miles. |

The coal of the Rock Springs group is mined at Superior, about 7 miles north of Thayer Junction. About 2 miles northeast of Superior are the Leucite Hills, which are made up largely of igneous rocks in the form of volcanic necks, sheets intruded into the stratified rocks, and dikes cutting across the sedimentary strata. Associated with these intrusive rocks are volcanic cones and lava flows. These rocks have long been objects of scientific interest because of their unusual character. Lately they have attracted additional interest by reason of the potash-rich mineral, leucite, they contain, which may some day be utilized if a process can be found for extracting the potash cheaply. It has been estimated that the igneous rock of the Leucite Hills contains more than 197,000,000 tons of potash.

|

Baxter. Elevation 6,303 feet. Omaha 803 miles. |

Baxter siding is near the center of the Rock Springs dome. The several eastward-dipping formations crossed between Bitter Creek station and Thayer Junction once arched over the top of this dome and now dip in the opposite direction on its western slope, as is indicated in the profile on the accompanying map (sheet 12). A mile west of Baxter siding a branch line runs northward 3 miles to Gunn, where mines have been opened on the lower beds of the Rock Springs coal group. Two miles west of the siding the route enters a picturesque gorge eroded by Bitter Creek through the ridge formed by the hard sandstone of the Mesaverde formation (Pl. XV, A, p. 67). Coal is mined from one of the beds that outcrop in the north wall of this gorge. From the west end of the gorge, just before the train enters Rock Springs, the traveler gets a magnificent view of White Mountain (Pl. XV, C), to the right, northwest of the town. This is the eastern escarpment of the plateau, made up of beds of Eocene (Tertiary) age that occupy the Bridger Basin. The rocks are the same as those that will be seen at close range from the town of Green River.

|

Rock Springs. Elevation 6,256 feet. Population 5,778. Omaha 809 miles. |

The city of Rock Springs derives its name from a large spring of saline water that issues at the base of a bluff of the water-bearing sandstone previously described as occurring between the Rock Springs and Almond groups of coal beds near Point of Rocks. However, water for domestic use as well as for use at the mines in this vicinity is pumped from Green River, a distance of 15 miles, with a lift of 179 feet.

Rock Springs is one of the most important coal-mining centers of the West and ships each year nearly a million tons of high-grade bituminous coal. The mines have been operated since 1868, when the Union Pacific Railroad reached this point, and some of the older workings extend for miles underground. Mine openings may be seen to the right (north) of the railroad east of the city. A branch line runs north to Reliance and another runs south to mines at Sweetwater. All the mines are in beds of the Rock Springs coal group.

West of Rock Springs the road passes from the Cretaceous formations to the Tertiary beds that occupy the Bridger Basin. The Tertiary rocks are conspicuous to the right (north) of the railroad, in White Mountain (see Pl. XV, C), which here forms the eastern rim of the basin. The mountain is made up of stratified rocks consisting of the light-pink beds of the Wasatch group and the white to light-blue and greenish rocks of the Green River formation. These beds are inclined gently toward the west, so that the light-colored beds of the middle portion of White Mountain descend to the river level, at the town of Green River.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec15.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006