|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

|

|

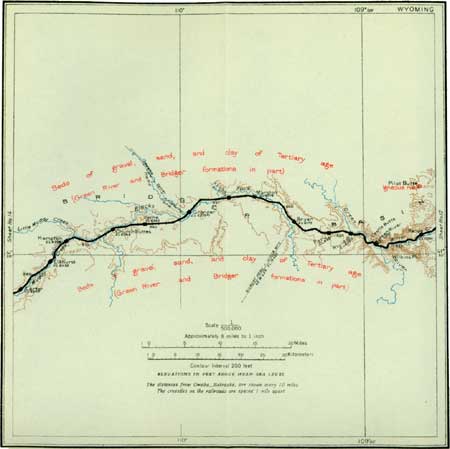

SHEET No. 13. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Kanda. Elevation 6,204 feet. Omaha 816 miles. |

Near Kanda (see sheet 13, p. 76) the train enters a narrow winding gorge which was eroded by Bitter Creek and whose walls show the westbound traveler first the pink beds of the lower part of the Wasatch group and then the harder sandy shales of the Green River formation. These beds are made up of a countless number of very thin and sandy calcareous layers separated by equally thin layers of shale, so that the cliffs of this formation have a wonderfully banded appearance. The gorge extends to the mouth of Bitter Creek,1 where the train suddenly emerges from its narrow confines directly into the broad valley occupied by Green River.

1In order to understand why Bitter Creek established itself in its present course, we must consider conditions that existed here millions of years ago. This stream cuts its way directly across the Rock Springs dome instead of flowing around it and then, seemingly regardless of what would be easy lines of erosion, flows across the broad valley west of Rock Springs and plunges through White Mountain, in which it has cut a gorge 1,000 feet or more in depth. This apparently unreasonable course was established long ages ago, when this part of the country was lower than it is now and the distant mountains, then newly formed and rugged, supplied the streams with more sediment than they could carry. This material was deposited on the lower lands, building them up just as flood plains and deltas are being built up in some places at the present time. The resulting accumulations of sediment constitute the Wasatch, Green River, Bridger and other formations of Tertiary age.

There came a time, however, when the region thus built up was uplifted so much as not only to stop deposition but perhaps also to divert the streams to new courses and cause them to cut downward into the beds of sediment which they had previously deposited. The surface was not raised the same amount in all places and the uplift was accompanied by warping and fracture of the rocks. East of Rock Springs the upheaval produced a great dome. In other fractured places the rocks slipped past each other and produced faults. These movements were very slow, and for this reason Bitter Creek maintained itself even while the great dome rose across its course. Doubtless similar movements are in progress now, but they are so slow that the lifetime of a man is not long enough to enable him to detect a change. The oldest inhabitant of Bitter Creek valley would probably insist that the creek had not deepened its channel during his lifetime, yet it cut its channel as fast as the dome rose, or it would have been deflected.

A similar explanation accounts for the behavior of this stream west of Rock Springs. Its course was established when the surface was a thousand feet or more higher than it is now—that is, higher than the present top of Table Mountain. As the master stream, Green River, cut its course lower and lower, the smaller stream, Bitter Creek, cut the narrow gorge through Table Mountain. But farther east, where the same sedimentary rocks that compose this mountain were more steeply upturned and more easily eroded, Bitter Creek and its tributaries cut down a vast area to a level much lower than the top of Table Mountain.

The volume of rock removed by this small stream alone would probably be reckoned in hundreds of cubic miles, and all of it found its way through the narrow gorge to Green River. Hundreds of other streams delivered similar amounts to the same river, and the question may well be asked, What became of it all? Those who have visited the Grand Canyon of the Colorado in Arizona have noted the muddy waters of that river and wondered where the mud came from. Some of it came from Wyoming. Those who have visited the built-up plains and filled basins that mark the ancient course of Colorado River in western Arizona have wondered where the material came from to fill these enormous basins. Some of it came from the valleys through which the Union Pacific Railroad is built. Those who have traveled over the Southern Pacific line in southern California, where it crosses the broad delta which the Colorado built out across the Gulf of California so far that the north end of the gulf—now the Salton Sink—was completely cut off from the main part of the gulf, have wondered where all the sand and silt of that great delta came from. Some of it once rested on the arch of the Rock Springs dome.

|

Green River. Elevation 6,077 feet. Population 1,313. Omaha 824 miles. |

The town of Green River (see Pl. XVII, A) is a division headquarters the Union Pacific Railroad and the point at which passengers for Oregon and Washington change to the Oregon Short Line. The Short Line trains, however, use the main line as far west as Granger. Green River is picturesquely situated between the river and the precipitous bluffs which rise 700 feet or more above the water. Like most of the other towns along the route throughout Wyoming it has little aside from the immediate business of the railroad to maintain it. An attempt has been made here to manufacture soda from alkaline water pumped from wells about 250 feet deep, but the long haul to market renders profitable operation difficult.

The town of Green River is on one of the most interesting drainage systems in America. The river rises about 200 miles farther north and at the railroad crossing is a stream of considerable size, having an average flow of 2,200 cubic feet a second. About 540 miles farther south it joins Grand River to form the Colorado, which, after winding through more than a thousand miles of the most wonderful canyon scenery in the world, reaches the Gulf of California.

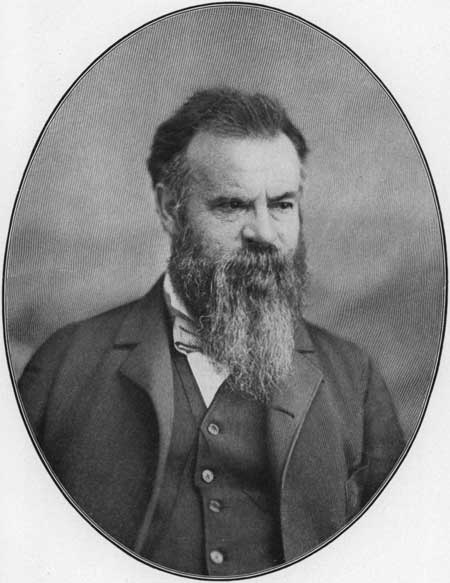

From the town of Green River, Maj. J. W. Powell, afterward Director of the United States Geological Survey, started May 24, 1869, with his little company of daring associates to explore the canyons of the Colorado. The story of the trip is well known, but from the simple, unimpassioned language in which Major Powell (see Pl. XVI) himself tells it, the reader might not realize that this was one of the most hazardous undertakings in the history of modern exploration. Few have cared to undertake the adventure since, and some of those have paid for their temerity with their lives. The journey has recently been successfully repeated, however, by two photographers, Ellsworth and Emery Kolb, who on September 8, 1911, also started from Green River and, after numerous adventures, emerged from the canyons with a valuable collection of negatives and moving-picture films.

|

| PLATE XVI.—MAJOR J. W. POWELL. |

The Green River beds, which form the bluffs near Green River, are carved into many curious and picturesque forms—natural monuments (Pl. XVII, B) and castle-like structures. The bluffs are light green in the lower part and dark brown above. The upper beds are harder than the lower ones and form the protecting caps of the pinnacles. These bluffs have been a source of interest to geologists and travelers ever since they were examined by F. V. Hayden more than 40 years ago, and they have been described and illustrated many times. Their character is indicated by the accompanying illustrations much better than by any word pictures.

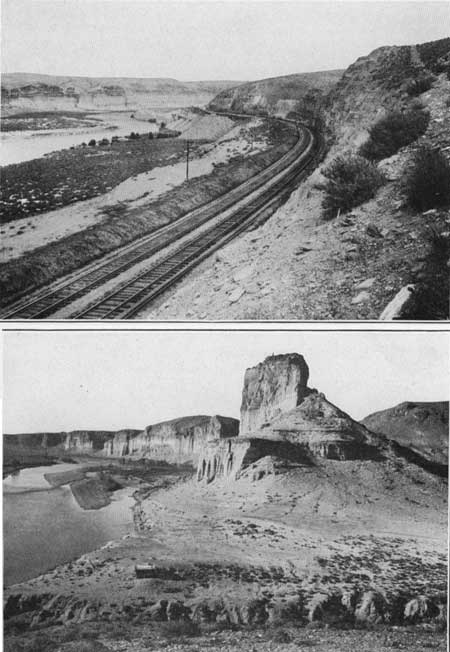

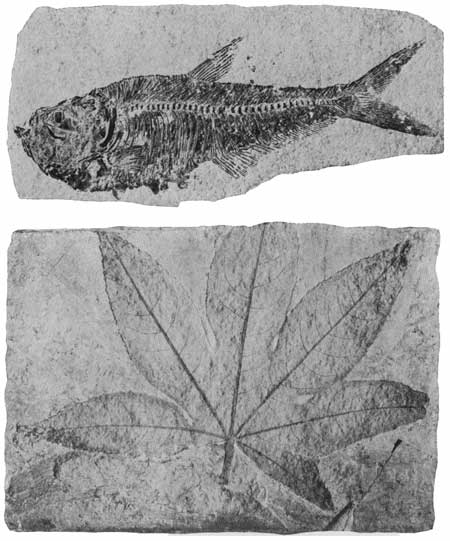

Three miles west of Green River the railroad passes through Fish Cut (Pl. XVIII, A), so named because of the large numbers of fossil fishes (Plate XIX, A), taken from it. Fossils are obtained from this same formation at Fossil, Wyo., a station on the Oregon Short Line, and sold as curios. On the side of the river opposite Fish Cut the Green River shale has been eroded into a variety of picturesque forms, such as are illustrated in Plates XVII, B, and XVIII, B. These may be seen to the right from the train.

|

| PLATE XVIII.—A (top), "FISH CUT," WEST OF GREEN RIVER, WYO. Many fossil fishes were found in the Green River formation at this locality. Photograph furnished by Union Pacific Railroad Co. B (bottom), BLUFFS OF THE GREEN RIVER FORMATION NEAR GREEN RIVER, WYO. Photograph furnished by Union Pacific Railroad Co. |

On the old grade just below the present road in Fish Cut there are several oil seeps, where the surface is kept moist by oil that oozes from the shale. Little oil occurs in the Green River formation. Its carbonaceous content consists of partly decomposed vegetal matter (see Plate XIX, B), which, when the rock is heated, yields petroleum and ammonia. Rock from Fish Cut that gave no outward sign of the presence of oil yielded, on distillation, 31 gallons of oil to the ton and an amount of ammonia equivalent to 34 pounds of ammonium sulphate, a product that is nearly as valuable as the oil.

|

| PLATE XIX.—FOSSILS FOUND IN THE GREEN RIVER (TERTIARY) FORMATION. A (top), FOSSIL FISH (DIPLOMYSTUS DENTATUS), SHOWING THE BONES, FIN RAYS, ETC., EMBEDDED IN A SLAB OF ROCK TAKEN FROM THE QUARRY. B (bottom), FOSSIL LEAF OF THE SWEET-GUM TREE (LIQUIDAMBAR) AS IT APPEARS ON A SLAB OF ROCK TAKEN FROM THE QUARRY. |

Just above the horizon at which the fossil fishes occur the shale gives place to brown coarse-grained cross-bedded sandstone, which occurs in such a way as to suggest that it fills old river channels. It is this channel sandstone that caps the curious pinnacles which are so conspicuous near Green River. The softer shale surrounding and underlying the masses of hard sandstone softens and crumbles under the influence of the weather and is washed by the rain or blown by the wind from the bluffs, the portions that are protected by the hard capping standing as isolated monuments or precipitous cliffs.

|

Peru. Elevation 6,381 feet. Omaha 831 miles. |

From Peru station the traveler may catch glimpses toward the southwest of the high peaks of the Uinta Mountains, in northwestern Colorado. These appear more conspicuous from points farther west.

From Green River the road rises by a relatively steep grade over strata that dip slightly to the west, and at Peru the younger Eocene or Bridger beds1 occupy the surface. Where they are cut by the railroad these beds consist of brown shaly or limy sandstone.

1The Bridger formation takes its name from Fort Bridger which stands in the valley of Blacks Fork about 10 miles south of Carter station. To the traveler on the train this formation is not readily distinguishable from the underlying beds, but many of the prominent buttes in this vicinity, especially those south of the track, are composed of rocks belonging to this formation. Probably those most noticeable from the train are the buttes near the station of Church Butte, which takes its name from the largest of this group.

Most of the formations exposed in western Wyoming and eastern Utah are designated by other names than those used for beds of essentially the same age that lie farther east. The following table shows the relations of these formations:

Succession of the rock formations exposed along the Union Pacific Railroad in western Wyoming and eastern Utah.

Period. Epoch. Group and formation. Tertiary. Eocene. Bridger formation.

Green River formation.

Wasatch group:

Knight formation.

Fowkes formation.

Almy formation.

Cretaceous or Tertiary. (?) Evanston formation. Cretaceous. Upper Cretaceous. Adaville formation.

Hilliard formation.

Frontier formation.

Aspen formation.

Bear River formation.Jurassic. Beckwith formation (possibly including some Cretaceous).

Twin Creek limestone.

Jurassic or Triassic. Nugget sandstone. Triassic. Lower Triassic. Ankareh shale.

Thaynes limestone.

Woodside formation.

Carboniferous. Permian (?). Park City formation. Pennsylvanian. Weber quartzite.

Morgan formation.Mississippian. Limestones. Devonian. Silurian. Ordovician. Cambrian. Algonkian. Archean. Granite, etc.

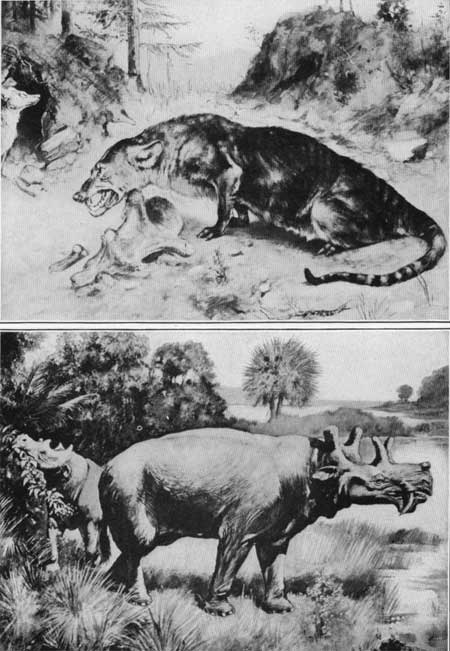

Great numbers of fossil bones, most of them representing primitive or unspecialized types of mammals, have been collected from the Eocene beds of the Bridger Basin. It was during the Eocene epoch that the great development of mammalian life took place. The small primitive mammals of earlier epochs were succeeded by a great variety of forms, some of which are the ancestors of animals now living, though others seem to have left no descendants. Two of the common forms are illustrated in Plate XX (p. 80).

|

| PLATE XX.—A (top), A CREODONT, AN ANCIENT DOGLIKE ANIMAL, ONE OF THE ANCESTORS OF THE CARNIVOROUS MAMMALS OF TO-DAY. After Osborn. Published by permission of The Macmillan Co. B (bottom), EOBASILEUS, ONE OF THE TYPES OF ANIMALS THAT BECAME EXTINCT AGES AGO. After Osborn. Published by permission of The Macmillan Co. |

|

Bryan. Elevation 6,173 feet. Omaha 837 miles. Granger. Elevation 6,279 feet Omaha 854 miles. Hampton. Elevation 6,396 feet Omaha 873 miles. |

Bryan, the home of 3,000 people during the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad, is now little more than a name in the desert. Toward the southwest, 60 miles away, may be seen the snowy summit of Gilbert Peak, one of the monarchs of the Uinta Mountains, rising 13,422 feet above sea level.

At Granger the Oregon Short Line branches off to the right from the Union Pacific, turning northward up Hams Fork. West of this station the Tertiary strata dip slightly toward the east, so that the westbound traveler passes gradually from younger to older beds.

From points between Granger and Hampton some of the distant summits of the Salt River Range may be seen on the right, far to the northwest, and the rugged, snowy peaks of the Uinta Mountains on the left, far away to the south. The hill south of the railroad, half a mile west of the station, contains great numbers of fossil shells. One layer of rock here, about 4 feet thick, consists almost wholly of coiled shells, of Eocene age, and another layer just below it contains numerous clamshells in an almost perfect state of preservation.

|

Carter. Elevation 6,507 feet. Omaha 882 miles. |

Carter consists of only a few houses but is the center of an extensive sheep-raising industry. During the summer the sheep are pastured on the distant mountains, but when the snow falls they are driven down to the desert plains, where they pass the winter.

West of Carter the red sandstone and shale of the Wasatch (Tertiary) group are again reached. These beds underlie the surface rocks that occupy the center of the Bridger Basin. Their material here is much coarser and of a deeper-red color than it is east of Green River. This change in character becomes more and more conspicuous toward the west, and near Evanston these rocks are markedly conglomeratic. Farther west, near the Wasatch Mountains, they are made up largely of a still coarser red puddingstone.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec16.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006