|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

|

|

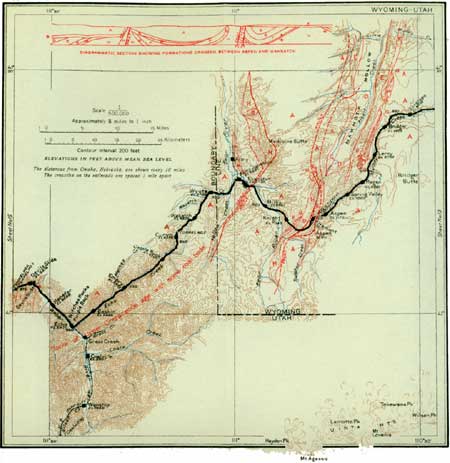

SHEET No. 14. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Between Carter and Bridger is Antelope station, at which the traveler will be nearly halfway from Omaha to San Francisco.

|

Bridger. Elevation 6,622 feet. Omaha 893 miles. |

Bridger station (see sheet 14, p. 88) was named for James Bridger,1 the first white man to settle in this section. Near the station the rocks of Upper Cretaceous and Jurassic age that underlie the Tertiary beds of the Bridger Basin begin to appear at the surface. About 3 miles north of the station where the railroad turns south, the hills formed by these older rocks are visible at the right (west), and the ridges formed by them lie nearly parallel to the road as far south as the Aspen tunnel. Throughout this distance the route traverses the valley eroded, by Muddy Creek, mainly in the Wasatch red beds, which here dip gently to the east.

1James Bridger was a well-known pioneer who did much toward taming the "wild West." Although he called Fort Bridger his home, he may more properly be spoken of as a citizen of the West, for he was at home beside the camp fire wherever night overtook him, whether on the plains or in the mountains, whether alone or surrounded by hostile savages.

He was born in Richmond, Va., in 1804, but soon drifted to the West, where he was employed by the Rocky Mountain Fur Co. So rapidly did he become familiar with the wilderness and with its savage inhabitants that before he was of age he was known as "the old man of the mountains." He discovered Great Salt Lake in the winter of 1824-25, and, because of the salinity of its waters, thought it was an arm of the Pacific Ocean. Two years later men under his direction explored the lake, passing completely around it in boats made of skins.

At his trading post on Black Fork, 10 miles southeast of the Bridger station, he built the fort that bore his name and which was later used by United States soldiers. Bridger was long employed as a guide for the Army in the several campaigns against hostile Indians, and also by companies of emigrants, especially by the gold seekers of 1849. He was in western Wyoming when the advance company of Mormons, led by Brigham Young, were on their way to the "promised land" and urged them not to settle in Salt Lake Valley, because of the supposed difficulty of ripening crops there. He said to Young: "I will give you a thousand dollars for the first ear of corn that ripens there." Young, who claimed divine guidance, replied: "Wait 30 years and we will show you."

|

Leroy. Elevation 6,702 feet. Omaha 898 miles. |

The original route of the railroad from Leroy up the valley of Muddy Creek and over the divide near old Bear River City has been abandoned. It was difficult to operate because of curves and grades that necessitated helping engines for all heavy trains. The new route follows the valley used by the Mormon pioneers in crossing Aspen Ridge.2 This ridge is pierced by the Aspen tunnel, which is 5,900 feet long and is the largest single piece of tunnel work performed by the Union Pacific Railroad Co. In order to hasten the work of construction a central shaft was sunk, the top of which was 331 feet above track grade. From the bottom of the shaft headings were started east and west to connect with the end headings. The greatest depth reached below the surface is 456 feet; the highest point above sea level 7,296 feet. The tunnel accommodates a single track and is lined with timber and concrete. The new route was completed in 1901, at a cost of $12,000,000, and shortens the line 10 miles.

2Aspen Ridge is the easternmost of a series of north-south ridges that are separated by troughlike depressions, of which Mammoth Hollow is a type. These ridges originated in mountain-making movements which probably began at the close of the Cretaceous period and resulted in the upheaval of the Uinta and Wasatch mountains on the south and the group of mountains extending southward from Yellowstone Park on the north. These ridges connect the groups of mountains and may be regarded as incipient mountain ranges. The rocks were broken or faulted and upturned in ridges, but the movement was arrested before high mountains were formed here.

Two main groups of fault lines are crossed by the Union Pacific in this general region. The Absaroka fault and the Oil Springs faults are crossed at the Aspen tunnel and the Almy and Medicine Butte faults at Evanston. The Absaroka is a thrust fault by which the rocks on the west have been pushed eastward and raised more than 15,000 feet, some of the older sedimentary rocks being brought to altitudes much greater than those of the younger rocks of this region. This relation is conspicuous west of the Aspen tunnel, where rocks of early Tertiary age abut against some of Jurassic age. The Medicine Butte fault, which the road crosses at Evanston, is also an over-thrust, but the Almy is a normal or gravity fault—that is, the rock mass here has dropped instead of being pushed upward.

Erosion, which followed the initial mountain-forming disturbance, carved the older rocks into low hills and shallow valleys, and these in turn were buried by accumulations of sediment in early Eocene time. Later the rocks were again upheaved, erosion was renewed, and other hills and valleys were carved out. These also were buried by the red sands and gravels of the Wasatch group, which recent erosion has removed in some places, exposing again the pre-Wasatch hills, but which still remain as the surface rocks over large areas of western Wyoming and eastern Utah.

At the point where the road leaves the main branch of Muddy Creek, 2-1/2 miles south of Leroy, the traveler may obtain a view, toward the left (east), of the edge of the plateau of Bridger beds on which stands Bridger Butte. A mile west of Ragan may be seen, to the right (north), a group of derricks where oil wells have been sunk into the Aspen shale,1 which includes the oil-bearing rocks of this region. A small refinery was built at Leroy, but it was not in operation in 1914.

1The Aspen formation consists of shale 1,500 to 2,000 feet thick, in which are layers of sandstone that contain oil. Near the top of the formation occurs the "Spring Valley oil sand," which contains the principal oil pools, although some have been found in lower sands. The formation is of marine origin, and the shaly parts contain numerous scales of fishes, from which they have been called the "fish-scale shales." Certain fossils found in the formation prove that it belongs in the lower part of the Upper Cretaceous series.

Although most of the oil of this region has been found in the Aspen formation, some comes from the Bear River formation, which immediately underlies the Aspen. The occurrence of oil in this region was known to James Bridger and other early trappers, but the first published account of it resulted from a visit made by the Mormon pioneers in 1847 to the natural oil spring, known as the Brigham Young oil well, 6 miles southwest of Spring Valley. Small quantities of oil were collected from this and other springs, and prospecting was carried on intermittently until 1900, when high-grade oil was struck in a well near Spring Valley. Since that time several pools have been found, but the yield is small, the best wells producing only a few barrels a day.

|

Spring Valley. Elevation 7,003 feet. Omaha 905 miles. |

Just west of Spring Valley station the train crosses a small exposure of the Frontier formation.1 These coal-bearing rocks are of Upper Cretaceous age and have been exposed because of the removal of the red beds of the Wasatch group that once covered them. Several abandoned prospects and old coal mines may be seen on each side of the track, but no coal is mined here now.

1The Frontier formation consists of coal-bearing sandstone and shale of Benton (Upper Cretaceous) age. Its name is derived from Frontier, Wyo., where the coals are well developed. The formation contains near the top a prominent sandstone about 200 feet thick, which usually forms a ridge at the outcrop and is characterized by the presence of fossil shells of a long, slender oyster (Ostrea soleniscus). Since 1858, when Englemann collected fossils from this sandstone on Sulphur Creek, it has been a favorite collecting ground for geologists, and from the time of the Hayden Survey, in 1872, it has been known as the Oyster Ridge sandstone. Fossil plants also have been collected from the Frontier formation.

|

Aspen. Elevation 7,175 feet. Omaha 909 miles. |

Aspen is a small station at the east end of the Aspen tunnel. From Granger the train has been ascending Muddy Creek and here reaches the head of one of its tributaries. In going through the tunnel the train passes from the area drained by Colorado River to the Great Basin—that portion of western North America which has no outlet to the sea. The waters east of Aspen Ridge find their way down Muddy Creek and Black Fork to Green River and thence through the Grand Canyon of the Colorado to the Gulf of California. Those west of this ridge find their way to Bear River and flow by a circuitous route into Great Salt Lake, from which they can escape only by evaporation.

The rocks at the east end of the tunnel are the red beds of the Wasatch group, but the Oyster Ridge sandstone may be seen in the ridge just above the mouth of the tunnel. The tunnel pierces this sandstone and also part of the Hilliard formation of Upper Cretaceous age, next younger than the Frontier.

|

Altamont. Elevation 7,217 feet. Omaha 911 miles. |

West of Altamont the route passes for about 2 miles through an open valley occupied by the soft Hilliard shale, then crosses the fault line that separates this shale from the Beckwith formation,2 the oldest formation exposed near the Union Pacific Railroad in western Wyoming, and enters a narrow gorge carved out of the hard conglomeratic sandstone of that formation. This sandstone, upturned to a nearly vertical position, now crops out in sharp ridges composed of coarse red conglomerate that is seen to best advantage toward right (north). These ridges were formed by mountain-making movements which fractured the once horizontal layers and shoved it up to a vertical position, and by erosion, which carved them into the present forms.

2The Beckwith formation comprises two members. The lower member consists of conglomerate, sandstone, and sandy clay 2,500 feet thick, light colored near the railroad, but red farther north; the upper member consists of light-colored sandstone and clay about 3,000 feet thick well exposed west of the railroad from Bridger to Leroy and in the ridges west of the Aspen tunnel.

Beyond this series of sharp ridges and well exposed in the gorge, on either side of the road, is the Bear River formation,1 which is here about 1,100 feet thick. In the lower part of this formation north of the track were found great numbers of fossil shells of clams and snails.

1The Bear River formation consists of dark shale, some of it carbonaceous, and thin layers of sandstone and limestone, and in some places it includes beds of coal. It may be distinguished from the older, unfossiliferous Beckwith beds by its darker color and by the fossils near its base.

Some parts of the formation contain numerous fossil plants, as well as shells of fresh-water and brackish-water mollusks, unlike those found in Cretaceous beds elsewhere. The formation is not widely distributed, being known only from Bear River City—an early construction camp of the Union Pacific near Bear River on the line now abandoned—northward to the Salt River Range. Its thickness ranges from 500 to about 5,000 feet.

The Bear River beds were formed not far from the continental land mass that remained above water throughout Upper Cretaceous time, west of the interior sea and it probably represents a delta at the mouth of a river that drained this old continent. The presence of fossil plants, coal beds, and fresh-water invertebrates in the Bear River formation, together with its stratigraphic position beneath the Aspen formation, which is known from fossils contained in it to be of Benton (Upper Cretaceous) age, has led to the somewhat persistent suggestion that the Bear River may be the time equivalent of the Dakota sandstone, although its maximum thickness is about 50 times that of the Dakota.

|

Knight. Elevation 7,043 feet. Omaha 916 miles. |

West of the narrow gorge in the Beckwith and Bear River formations is a small open space in which the Aspen shale crops out. Still farther west the route again enters an area occupied by the red beds of the Wasatch group. The Wasatch of this region consists of the Almy, Fowkes, and Knight formations, the last having been named from Knight station.

About 2 miles west of the station the train reaches the open valley of Bear River, a broad marshy flood plain over which the river meanders in a serpentine course and which at times of high water is completely flooded. Bear River rises in the Uinta Mountains, about 50 miles to the south, and flows in a circuitous route, first northwestward and then westward, around the north end of the Wasatch Mountains, and finally doubles back upon itself in a general southerly course and empties into Great Salt Lake. Measurements of its flow show that on the average 375 cubic feet of water passed Evanston every second in 1914. The current is swift in some places, and from this point in its course to its mouth the river falls about 2,500 feet. Water from Bear River and its tributaries is utilized for irrigating about 75,000 acres of land.

|

Millis. Elevation 6,883 feet. Omaha 920 miles. |

Near Millis station may be seen to the right (north) great piles of railroad ties that were cut in the mountains many miles to the south and floated down Bear River at times of high water. To the left (south) are bluffs formed by beds of gravel lying horizontally over the eroded edges of the upturned red beds of the Knight formation. These gravels were deposited by the river ages ago, before it had cut its valley down to the level of the present flood plain.

Just before entering Evanston the road crosses the lines of the Almy and Medicine Butte faults. Between these two faults the rocks are steeply tilted, and to the left (south) may be obtained a glimpse of the Almy conglomerates and the Evanston formation, a coal-bearing formation that is best exposed north of the city.

|

Evanston, Wyo. Elevation 6,739 feet. Population 2,583. Omaha 925 miles. |

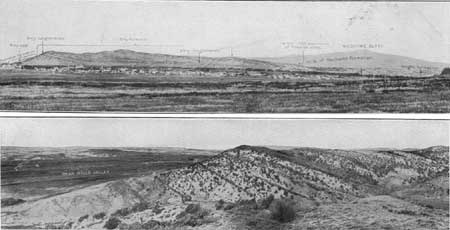

Evanston is the seat of Uinta County and takes its name from John Evans, a civil engineer, who founded it in 1869. It is a coal-mining and commercial center and a division point of the Union Pacific Railroad, with machine shops, icing plants, and other buildings. A branch road connects the city with several mines, some as far north as Almy. The Evanston formation, which contains the principal coal beds of this region, is well exposed in a hill that may be seen to the right, about 2 miles north of the city. Plate XXI, A, shows the relations of this formation as seen from Evanston. The type locality of this formation is east of Bear River, just north of the City, at the locality shown in Plate XXI, B. Its rocks consist of conglomeratic sandstone, shale, and thick beds of coal. It lies on the eroded edges of several older formations, indicating that its deposition followed a long period of erosion. (See table on p. 75.)

|

| PLATE XXI.—A (top), GEOLOGIC FEATURES SEEN FROM POINT SOUTH OF EVANSTON, WYO., LOOKING NORTH. B (bottom), DETAILS OF PROMINENT HILL AT LEFT OF VIEW SHOWN IN A. The line of parting between the Evanston and Almy formations lies between the points A and B. Upper beds are conglomeratic Almy; lower are Evanston. The hills across the irrigated valley of Bear River are composed of nearly horizontal strata belonging to the Knight formation. |

Six miles west of Evanston the railroad crosses from Wyoming into Utah.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec17.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006