|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

| Utah. |

Utah has an area of 82,184 square miles and a population of 373,351. The eastern part of the State consists of high plateaus; the western part, which lies in the Great Basin,1 consists of ranges of rugged mountains trending in general from north to south, sagebrush-covered hills, wide, nearly level valleys, clear mountain streams, and fresh and salt lakes. The floor of the Great Basin is formed of alluvium washed from the plateaus and mountains.

1As a general rule continental surfaces are drained by streams flowing to the ocean, but there are some exceptional areas which have no outward drainage. The Great Basin (fig. 10) is such an area. It was so named by Frémont, who was the first to gain an adequate conception of its character and extent. It lies near the western margin of the continent and is surrounded by the headwater divides of rivers tributary to the Pacific Ocean.

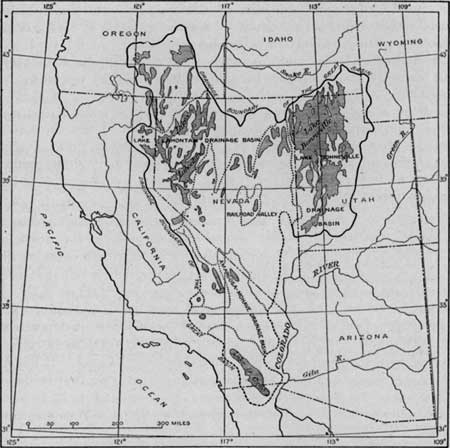

FIGURE 10.—Map showing outline of the Great Basin and the lakes it once contained, shaded areas show Quaternary lakes; dotted lines show boundaries of drainage basins. Roughly, the Great Basin is bounded by the Rocky Mountains on the east and by the Sierra Nevada on the west. It extends from Oregon on the north to and beyond the Mexican boundary, but is limited by the drainage system of Colorado River on the southeast. The area thus defined is 800 miles long from north to south, and nearly 500 miles broad in its widest part. It contains 200,000 square miles, an area about equal to that of France.

The Great Basin is a region of diversified surface features, including flat desert valleys and ragged mountain ranges containing lofty peaks. It is not, as its name might suggest, a single pan-shaped depression, gathering its waters to a common center, but is divided into a large number of independent drainage areas. Both the mountains and the valleys are of types more or less peculiar to the region. The mountains are long, narrow ridges, most of which extend from north to south and project abruptly out of the plains, there being a noticeable absence of foothills, Many of them terminate at the ends as abruptly as their side slopes join the surrounding plains.

Arid plains are abundant in this region and some are so extensive that they appear almost boundless. They present many of the features generally supposed to characterize a desert, such as deep drifting sands and broad stretches of wholly barren mud plains, and in the heat of the midday sun they exhibit all the tricks of the mirage.

The climate of the region is very dry, the average annual rainfall varying from 10 or 12 inches in northern Nevada to less than 3 inches in the south and southwest. In northern Nevada the plains are in general covered with scattered clumps of brush, of which greasewood (Sarcobatus) and numerous varieties of sage (Artemisia) are most common. In the spring the barren-looking soil brings forth a surprising variety of beautiful and delicate flowers, most of which disappear entirely as the parching heat of summer comes on. Timber or even trees of any kind are, as a rule, exceedingly scarce. Cottonwoods and willows grow in patches or line some of the more permanent water-courses, and more or less scrubby pines and cedars are scattered on some of the higher mountain slopes. Herds of small wild horses, or mustangs, roam over some of the less frequented mountain ranges, but, like the ubiquitous coyotes, they are shy and are not likely to be seen from the train.

Agriculture is almost wholly restricted to a few areas that can be irrigated, although dry farming is being tried in some localities. A more common industry is the grazing of sheep and cattle on the bunch grass that grows in the shade of the sagebrush.

The mines of the precious metals are the principal source of wealth in the Great Basin, and in connection with their development towns have been built in out of the way places, many of them high on the bare mountain sides and far from water and food supplies.

Since the completion of the first transcontinental railroad, in 1869, settlement of the region and development of its resources have progressed enormously. Now several transcontinental railroads cross it and numerous branches extend through the desert valleys north and south from the trunk lines; towns and mining camps have sprung up along these highways, and almost every acre of easily irrigable land has been appropriated by settlers. Herds of cattle and sheep find sustenance on the mountains and in the sagebrush-covered valleys that were once thought to be too barren ever to become of service to man. Throughout the eastern border of the Great Basin, in Idaho and Utah, the followers of the Mormon faith have found a "promised land" which, by great industry, they have reclaimed from its primitive desolation and made the home of thousands. Some of the most productive gold and silver mines in the world have been developed in this inhospitable region. With all this advancement, however, the Great Basin is still very sparsely settled.

Although not generally attractive to the pleasure seeker, the Great Basin appeals especially to the geologist, both because the absence of vegetation gives unusual facilities for investigation and because the problems to be solved are peculiarly interesting and economically important. There is, moreover, an attraction in the region that grows with more intimate acquaintance, and that is due partly perhaps to its vastness, its clear dry air, and the free and healthful life that it seems to induce. Although the region is generally called a desert, its climate compares favorably with that of many other parts of the country. The low humidity prevents the high temperatures of summer from being oppressive, except possibly in some of the low-lying southern valleys where the heat is almost unendurable. It is true that the wind blows fiercely at times, so that the air is filled with flying dust and sand, but these storms are infrequent. The country probably appears to least advantage viewed from the windows of a Pullman car. From such a position of comfort the heat and dust of a summer's day appear unnaturally intensified and the apparent lonesomeness of a strange and unknown country is likely to be repellent.

The great mineral wealth of the State is shown by its record of mineral production, which in 1913 amounted to more than $53,000,000. The five leading products in that year were copper, $25,024,124; silver, $7,903,240; lead, $7,309,579; coal, $5,384,127; and gold, $3,565,229. Utah is third among the States in the Union in the production of silver and lead and fourth in the production of copper. Among the State's nonmetallic mineral resources are coal, which underlies large areas, and phosphate rock.

Although the average annual rainfall in Utah is only 11 inches, large crops are grown, chiefly by irrigation, and great numbers of live stock are raised. The value of the sugar made from sugar beets in 1914 amounted to more than $10,000,000. Wheat, oats, and potatoes are raised in large quantities, the value of these products in 1913 having been more than $8,000,000. The live stock in Utah in 1914 was valued at $18,000,000, and the value of the wool clip was $7,000,000. The value of the manufactures of the State in 1914 amounted to about $76,000,000.

To the geologist Utah is an interesting field of work and study. Its peculiar mountain ranges, the record of its extinct lakes, the deposits in its present lakes, its coal beds, its possible gas and oil fields, and its diverse and abundant mineral deposits, as well as its underground water and its available water powers, have long commanded attention and have been the subjects of many reports.

|

Wahsatch, Utah. Elevation 6,824 feet Omaha 935 miles. |

Wahsatch, which consists of little more than a station house, stands at the crest of the divide between Bear River and Weber River. The name of the station retains the old spelling, which has been simplified for the name of the mountains. From many points west of this station may be had glimpses of the Uinta Mountains, to the southeast, and of the Wasatch Mountains, to the southwest. Toward the west may be seen the northward extension of the Wasatch Range. The hills near by consist of the red and yellow sandstone, shale, and conglomerate of the Wasatch group, which occurs here in typical development. It was from this region that Dr. Hayden, Director of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, named these strata.

A short distance west of the station the railroad passes through a tunnel in these red rocks and enters Echo Canyon, which is famous for the curious forms carved by erosion from the red conglomerate of its walls.

|

Curvo. Elevation 6,824 feet. Omaha 939 miles. Castle Rock. Elevation 6,240 feet. Population 131. Omaha 944 miles. |

The first station in this canyon has been named Curvo, because of the route taken by the railroad in its vicinity. Many of the sharp curves and steep grades of the Union Pacific as first built have been eliminated by recent improvements, but it is not easy to smooth out all the rough places, especially where the road is confined in a narrow valley.

The station of Castle Rock takes its name from the castellated form of the north wall of the canyon which overlooks it. The red beds are here carved by erosion into many fantastic shapes, and the peculiar forms seen here become more numerous farther west and culminate in grotesqueness near Echo.

|

Emory. Elevation 5,925 feet. Omaha 950 miles. |

Two miles east of Emory light-colored conglomeratic sandstone appears in the canyon wall to the right (north), steeply inclined beneath the red beds of the Wasatch group. These tilted beds contain fossil plants that indicate Cretaceous age. Near Emory station a thickness of several thousand feet of these beds is exposed. The conglomerates are very coarse near the top and are colored light red, so that they can not always be distinguished from the overlying conglomerates of the Wasatch group.

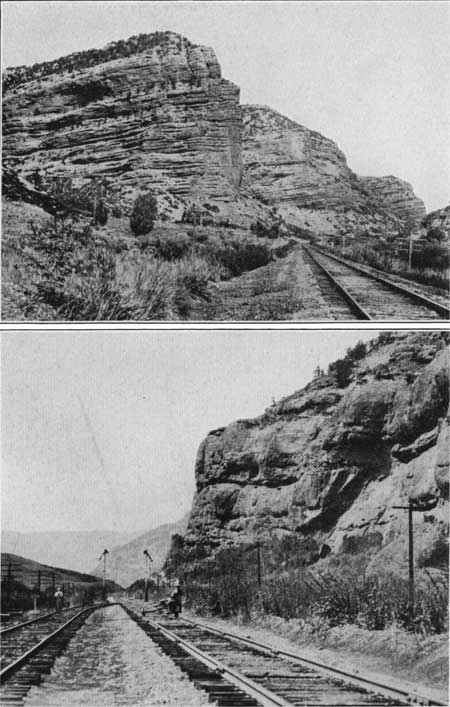

In Echo Canyon west of Emory there is some of the most picturesque scenery on the Overland Route. After passing over the great stretches of flat, unbroken desert farther east, where little but sage brush and sand can be seen, the traveler is here refreshed by seeing something that has a vertical dimension. Some of the cliffs are nearly 1,000 feet high. The canyon has been carved by the stream, the rains, and the wind, working through long ages on the red conglomerate, which, because of inequalities in hardness, has been worn into many a curious and fantastic shape whose general effect can not be adequately described and is only poorly represented by the camera. Many of the forms have received fanciful names suggested by their shapes, such as "Jack in the Pulpit," "the Sphinx," "the Giant's Teapot," "Steamboat Rock," and "Gibraltar." (See Pl. XXII, A.) The imaginative spectator may be able to distinguish the forms suggested by these names, but the more observant will rather be impressed by the evidences of the working of the great forces of nature here so conspicuously displayed.

|

| PLATE XXII.—A (top), "STEAMBOAT ROCK," IN ECHO CANYON, UTAH. Name is applied to rock mass in foreground because seen at some angles it resembles the bow of a steamship. It consists of red conglomerates of Tertiary age. B (bottom), THE NARROWS, IN ECHO CANYON, UTAH. Fortifications were constructed by the Mormons in these narrows during the so-called Mormon war of 1857. The walls are composed of coarse red conglomerate of the Wasatch group. |

Echo Canyon is in places very narrow and long stretches of its north wall are almost vertical. (See Pl. XXII, B.) On top of this wall may still be seen the rude fortifications built by the Mormons during the so-called Mormon war of 1857 to prevent the entrance of United States soldiers into Salt Lake valley. Here the defenders watched and waited for the battle that was never fought, for the misunderstanding—or worse, according to Bancroft's "History of Utah"—was adjusted before the troops reached the canyon.

|

Echo. Elevation 5,471 feet. Population 144. Omaha 960 miles. |

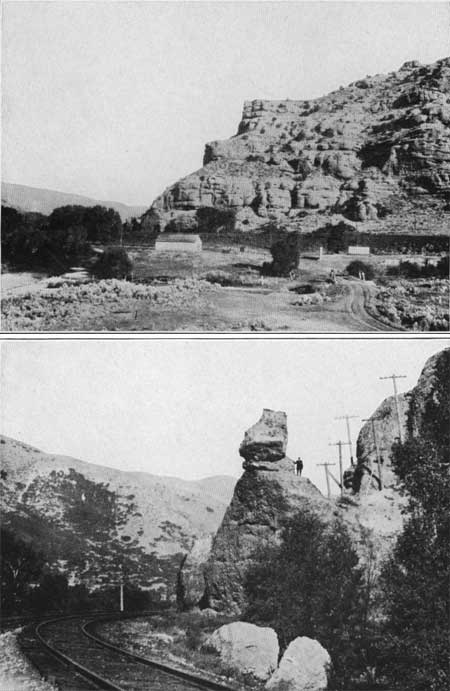

Just before entering the town of Echo the train passes close to Pulpit Rock (see Pl. XXIII, B) which may be seen on the right. As the name implies, this rock bears some resemblance to a pulpit, and the story has been somewhat widely circulated that from it Brigham Young preached his first sermon on entering the "promised land" in 1847. However, those in position to speak with authority on this subject say that the first company of Mormon emigrants did not stop at Pulpit Rock and that Young was sick with mountain fever during this part of the journey.1

1Many of the facts relating to the Mormon immigration have been kindly furnished by Mr. Andrew Jensen, of Salt Lake City.

|

| PLATE XXIII.—A (top), NORTH WALL OF ECHO CANYON, UTAH, AT ITS JUNCTION WITH WEBER CANYON, NEAR THE TOWN OF ECHO. The rocks consist of coarse red conglomerate of the Wasatch group. B (bottom), PULPIT ROCK AT ECHO, UTAH. Composed of red conglomerate. |

At the town of Echo the canyon opens into Weber Valley, up which a railroad spur extends through the coal-mining town of Coalville to the metal-mining district surrounding Park City.1 Coal was found by the Mormon settlers near Coalville long before the Union Pacific was built and has been mined more or less continuously ever since its discovery. The mines of the Grass Creek valley, in the Coalville field, now furnish fuel for the mining operations at Park City and for the manufacture of Portland cement at Devils Slide.

1The mining camp at Park City is on the east side of the Wasatch Range at an altitude of 7,200 feet, but some of the mines are nearly 2,000 feet higher. The sedimentary rocks of this district, ranging in age from Carboniferous to Triassic, were long ago compressed into a series of folds and broken by mountain-making forces and large portions of them were greatly displaced. Masses of molten rock known as quartz diorite and quartz diorite porphyry were then forced up into them from below. Later other masses of molten rock called andesite flowed over the surface.

The ores result from the older intrusions and occur as compounds of lead, silver, copper, zinc, and other metals in lodes and fissure veins and as bedded deposits in the sedimentary rocks. The more important lode deposits occur in two zones about a mile apart, known as the Ontario and Daly West zone and the Silver King and Kearns-Keith zone. These have been explored for several thousand feet (in length), and in the Ontario mine a fissure containing much valuable ore has been explored to a depth of 2,000 feet or more.

Ore was discovered in this district in 1869, but not until 1877 did the camp become an important producer. Since that time production has been continuous. The total reported output to the close of the year 1913 was gold $3,959,132; silver, $91,336,065; lead, $47,602,156; copper, $3,587,247; zinc, $2,606,770—a total value of $149,091,370, of which $38,753,126 has been distributed as dividends.

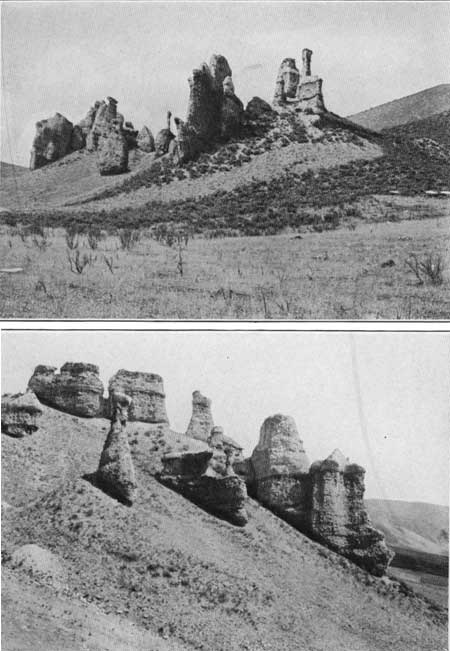

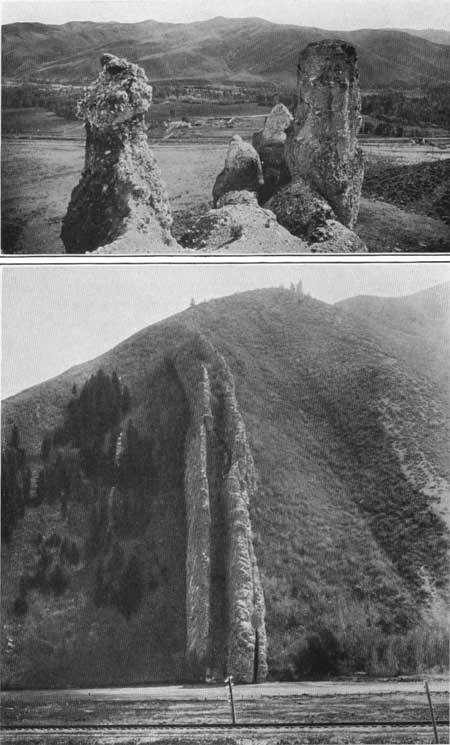

At Echo the red conglomerates (Wasatch) form cliffs 500 feet or more in height (Pl. XXIII, A). South and west of the town the rocks of Cretaceous age reappear at the surface where the Wasatch beds have been eroded away. About 2 miles west of Echo a group of curious monument-like rocks, some of which are more than 100 feet high, may be seen to the right (north) of the track, well up the slope. These are known as The Witches (Pl. XXIV, A) and are remnants formed by the erosion of a coarse conglomerate. Although any rock that has a fancied resemblance to some familiar shape is likely to attract greater attention than many a more significant feature of the landscape, these bizarre monuments are well worthy of more than a passing glance. The name "The Witches" is suggested by the form of the cap rock of one of the monuments, which is shaped something like the fabled witch's hat. (See Pl. XXIV, B.) The caps are formed from a light-colored band of conglomerate that is cemented into a harder mass than the underlying pink conglomerate. This hard cap rock protects the underlying beds from the rain until the supporting column, by slow crumbling, becomes too slender to hold it. When the cap falls off the monument soon becomes pointed at the top and is finally reduced to the level of the surrounding country. Plate XXIV, A, shows a monument (in the center of the group) that is lower than the others and worn to a sharp point at the top. The cap that once protected this "witch" now lies in a gulch at her feet. The other caps will fall in time—probably after the lapse of centuries—and The Witches, like their mythical prototypes, will disappear from the face of the earth.

|

| PLATE XXIV.—A (top), THE WITCHES, NEAR ECHO, UTAH, AS SEEN FROM THE TRAIN. A group of natural monuments carved by wind and rain from conglomerate probably of Tertiary age. B (bottom), SIDE VIEW SHOWING, ON THE BUTTE TO THE RIGHT, THE "WITCH'S CAP," WHICH SUGGESTED THE NAME FOR THE GROUP. |

|

Henefer. Elevation 5,409 feet. Population 413. Omaha 964 miles. |

Near Henefer the first company of Mormon emigrants, for some reason that is now hard to understand, left the Overland Trail and chose the very difficult route up the creek that enters the Weber from the south. After crossing the mountains, they passed down Emigration Canyon to Salt Lake City.1

1It is possible that a little study of the earlier history of the Mormons may throw some light on this strange procedure. They had been driven from place to place in the States until they had decided to seek a place so far from settled districts that they would not be molested. When this first company, consisting of 140 men and 3 women, started westward in April, 1847, one purpose of their leader, Brigham Young, was to mark out a trail for the use of later emigrants. Rather than follow the Overland Trail, which had become fairly well known by this time, he chose a new and untraveled route that came later to be called the Mormon Trail. The beaten path was avoided for two reasons. First, they wished to avoid their enemies, some of whom they would be sure to find on the older trail, and second, they never traveled on Sunday and they made religious worship as much a part of their daily program as the travel itself. In order to avoid trouble, as well as for the sake of being unmolested in their devotions, this first company marked out a new route through 1,000 miles of wilderness. The Mormon Trail parallels the Overland Trail and in some places where a different route was impracticable joins it, as, for example, at river crossings and in the mountain passes and canyons.

To the right (north), near Henefer station, may be seen a gravel terrace rising 25 feet or more above the level of the road bed. This was formed by the river at some former stage, probably during the time of high water in Lake Bonneville. (See pp. 97-99.) Although the gravels here are more than 200 feet above the highest terrace of the old lake, it seems likely that the diminished slope of the river during high water then caused the stream to deposit in this part of its course the beds of gravel that now form the shelf on which the railroad is built west of Echo and that form the protecting cap of the bluff at Henefer.

The Cretaceous rocks which in Echo Canyon dip steeply toward the west under the red beds of the Wasatch group reappear with opposite dip west of Echo, but owing to the great quantities of gravel that cover the hillsides, derived by disintegration from the older conglomerates, these rocks can be seen from the train at only a few places. However, the broad, open valley that the route crosses west of Henefer is due to erosion of the soft Cretaceous shales.

Three miles west of Henefer the coarse red puddingstone of the Wasatch beds extends down to the river level, and the broad basin-like valley suddenly narrows to a gorge barely wide enough for the river to pass through. The road bed has been cut in the side of this gorge, and in the cuts may be seen great bowlders of quartzite, some of them 4 feet in diameter, with smaller bowlders, pebbles, and sand filling the space between them. These materials are cemented into a resistant mass by red oxide of iron, which gives a brilliant color to the whole mass. At the west end of this short gorge the red conglomerate overlaps rocks of Jurassic age, which have been upturned to a vertical position.

|

Devils Slide. Elevation 5,314 feet. Omaha 969 miles. |

On emerging from the gorge, just before entering the town of Devils Slide, the train passes through a long cut in the shale of the upper part of the Jurassic and crosses Weber River at the point where Lost Creek enters it from the right (north). To the right also, in the Lost Creek valley, may be seen a large mill where limestone and shale are manufactured into Portland cement.1 These stratified rocks are all turned up into a vertical attitude. The soft shale is worn away by rain and wind faster than the limestone, which is left standing out as ragged vertical walls. The Devils Slide (Pl. XXV, B) is formed by two of these limestone reefs, about 20 feet apart, from which the shale has been eroded away, leaving them standing about 40 feet above the general slope of the canyon side. Many other reefs in this vicinity are equally prominent, but no others are so conspicuous from the train.

1The Jurassic limestone and shale of this locality are utilized in the manufacture of cement, for which they are well adapted and conveniently located. The rock is blasted from the mountain side in quarries plainly visible from the train to the right (north) and passed downward through the mills, coming out at the bottom in the form of cement at the rate of about 2,500 barrels a day. The fuel used for the kilns is coal, mined on Grass Creek. Electric power is furnished by streams on the western slope of the Wasatch Mountains and transmitted from generating plants near the base of the range.

|

| PLATE XXV.—A (top), VIEW OF THE VALLEY OF WEBER RIVER FROM WITCHES ROCKS. On the monument at the left is a cap which protects the rock under it because its pebbles are cemented together more firmly than those below. (bottom), THE DEVILS SLIDE. These beds consist of layers of hard limestone separated by soft shale of the Twin Creek formation of Jurassic age, and were originally formed in a horizontal position but during one of the mountain uplifts were upturned to a vertical position. |

From Devils Slide westward to Morgan Weber River has cut a canyon through the Bear River Range. This broad range is by some geographers included in the Wasatch Mountains, into which it passes farther south. The sedimentary rocks of the Bear River Range consist of steeply inclined beds of limestone and sandstone and a subordinate amount of shale, ranging in age from Jurassic on the east to Ordovician on the west. (See table on p. 2.) The formations are all conspicuously exposed in the precipitous craggy sides of the canyon and may be seen to best advantage toward the right, in the north wall of the canyon. West of the town of Devils Slide the gray beds of the Jurassic Twin Creek limestone give place to a massive salmon-colored sandstone (Nugget sandstone) of Jurassic or Triassic age, west of which, and next older, are thin-bedded bright-red shales and sandstones (Ankareh shale), fossiliferous shaly limestone (Thaynes limestone), and red sandstone and shale (Woodside formation), all probably of Lower Triassic age. The purplish-red sandstone layers of the Ankareh are beautifully ripple marked.

Still farther west appears the fossiliferous limestone of the Park City formation, of Pennsylvanian or Permian age. In the lower part of this formation are beds of black phosphate rock interstratified with beds of shale and limestone. The traveler can see some old prospect openings in the phosphate beds to the left, in the south wall of the canyon, just before the train enters the tunnel. These beds are portions of the great phosphate deposits of Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, which form a large part of the nation's store of material available for making phosphatic fertilizers. (See pp. 127-129.)

West of the phosphate beds is the Weber quartzite, a thick formation of Pennsylvanian age which, because of its superior hardness and resistance to erosion, forms the crest of the Bear River Range. Most of the rounded quartzite bowlders and pebbles in the red conglomerate of Echo Canyon and of the gorge east of Devils Slide were derived from this formation.

The river has cut a winding gorge though the quartzite, and two of the projecting spurs of the craggy walls are pierced by short tunnels. At the eastern tunnel the strata, which farther east are nearly vertical, are bent into a knee-shaped fold that brings the beds west of the axis to an inclination of scarcely 15°.

The second tunnel in the Weber quartzite opens on the west into Round Valley, a circular basin hollowed out by the river in the relatively soft red sandstone and shale of lower Pennsylvanian age, known as the Morgan formation, because of its occurrence near the town of Morgan. These red beds are well exposed in the north wall of Round Valley and also south of the railroad between this valley and Morgan.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec18.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006