|

Geological Survey Bulletin 613

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C. The Santa Fe Route |

ITINERARY

|

Abajo. Elevation 4,945 feet. Kansas City 920 miles. |

On leaving. Albuquerque the train goes nearly due south, passing Abajo (see sheet 14, p. 98) and continuing along the east side of the Rio Grande valley for about 10 miles. To the west is a mesa of moderate height, capped by a thin sheet of lava which appears to have flowed from several small cones rising above its surface some distance back on the mesa and in plain view from the trains. This lava lies on the Santa Fe marl, which occupies the Rio Grande valley through the greater part of central New Mexico. The railway crosses the Rio Grande1 10-1/2 miles from Albuquerque and follows the west bank 2 miles to Isleta.

1This stream is one of variable volume; during the dry season it dwindles to a few small shallow channels and even becomes dry at the surface in many places, but early in the summer and sometimes at intervals later it carries great floods, which usually overflow most of the adjoining lower lands. For a large part of the year the flow near Albuquerque averages about 1,500 cubic feet a second, but in some years the average flow is less than 500 cubic feet a second. At times of flood the volume of water is 10,000 to 20,000 cubic feet a second or even more. It is estimated that the average total yearly flow is sufficient to cover 400,000 acres (625 square miles) to a depth of 3 feet, which is the amount required for most irrigation in this region.

The great differences in flow are due to the variations in the amount of rainfall and in some degree to the nature of the country drained by the river. The greater part of the surface in the Rio Grande basin has a very scanty cover of vegetation, so that but little of the rainfall is absorbed by the soil or passes underground; therefore it runs off rapidly into draws and creeks and soon reaches the river. Most of the rainstorms, though relatively short, are violent, and when the storm area is large a vast amount of water is carried into the river.

As a rule, most of the water of river floods is lost, for the water used for irrigation is taken out at times when rivers are at the ordinary stage of flow, and no provision is made for storing the floods. In the Rio Grande valley, however, this condition is soon to be changed, for the United States Reclamation Service is building a storage dam near Elephant Butte, about 140 miles below Albuquerque. The dam will be 1,200 feet long, 300-feet high, and 215 feet wide at the base and will contain 600,000 cubic yards of masonry. It will create a lake 41 miles long, extending nearly to San Marcial with an average width of 1-3/4 miles and a capacity of 862,000,000,000 gallons, or more than 2,500,000 acre-feet. This basin will hold the floods of the Rio Grande and conserve the water for use when needed for irrigation all along the river in southern New Mexico and Mexico. Of course it will not prevent floods in the Albuquerque region and higher in the valley, but it will save that water for use in a region where it can be utilized advantageously for irrigation. In January, 1915, the Elephant Butte dam was said to be about two-thirds built, and a large volume of water will be held in 1915.

|

|

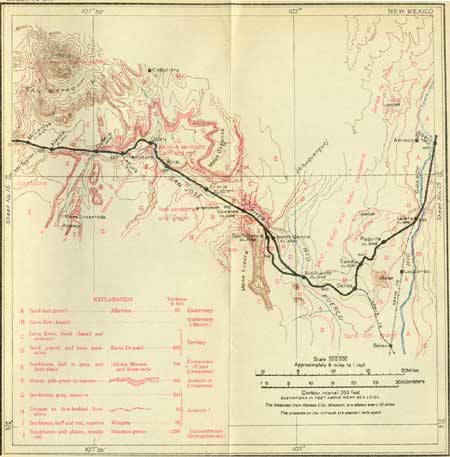

SHEET No. 14 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Isleta. Elevation 4,896 feet. Population 1,085.* Kansas City 930 miles. |

Isleta consists mainly of an Indian pueblo built on the bank of the river a short distance east of the railway. This pueblo may be seen best from points a short distance north of Isleta station.1 Isleta, named thus by the Spaniards on account of its location on an islet in the Rio Grande, was discovered by Coronado in 1540. It was a Tiguex village but has had accessions of Indians from other pueblos. At the time of the rebellion of 1680 it revolted, together with the other Tiguex villages of the Bernalillo and Santa Fe region. The Spanish governor stormed it and captured over 500 natives. These were sent as captives to El Paso and the rest of the tribe fled for refuge to the Hopi pueblos in Arizona. Early in the eighteenth century the pueblo was resettled under the name San Agustin de la Isleta.

1This station is at milepost 915. The numbering of the mileposts from Atchison continues south from Isleta along the El Paso branch line. Mileposts on the main line west of Isleta indicate distance from Albuquerque.

From Isleta, on the Rio Grande, which flows into the Gulf of Mexico, the railway begins its long journey across the interesting plateau country, which, with its bordering areas, extends almost to Colorado River, which flows into the Pacific. This vast area of high, nearly level country lies between the rugged and generally higher ranges of the Rocky Mountains to the north and the alternating short ranges and deserts of the lower lying north end of the Mexican plateau country to the south.

This is a land of interesting landscapes, rocks, and people. In places the plains and cliffs are vividly colored by natural pigments of red and vermilion. The rocks of the plateau are surmounted by two large volcanic piles, which stand far above the general level of the plain and which were master volcanoes in but comparatively recent time—Mount Taylor on the east and the San Francisco Mountains on the west. From the immensely thick, almost horizontal sedimentary strata that compose most of the mass of this plateau layer after layer has been eroded away over wide areas, leaving remnants of harder strata which make picturesque cliffs and valleys and exposing fossil forests that were long ago buried in the sediments of which these strata are made. Erosion has also carved many canyons, notably the majestic Grand Canyon of the Colorado.

Here and there in the rocky cliffs and canyons are the present and former communal homes of aboriginal peoples, whose arts and religious ceremonials partly lift the veil of the past and reveal glimpses of earlier stages of human culture. These vast expanses were long ago the abode of aboriginal tribes; later they were explored and dominated by the mounted Spanish conquistadores; and finally they have been made accessible to all by the comfortable railway of to-day. The plateau country and its approaches, in all their aspects—geologic, ethnologic, and historical—form a region which will hold the attention of all passers-by in whom there exists a spark of appreciation of striking natural phenomena and significant human events.

|

Sandia. Elevation. 5,286 feet. Kansas City 941 miles. |

A short distance beyond Isleta the main line of the Santa Fe begins its climb out of the valley of the Rio Grande, ascending by a rather steep grade to the mesa which lies west of the river flat. The crest of this mesa is reached at Sandia siding.1 In the cuts on this ascent there are many exposures of sands and loams (Santa Fe marl) which are capped by sheets of lava and volcanic cones on both sides of the track. The railway reaches the edge of the lava sheet a short distance beyond milepost 16 and passes over it for 2 miles or more. There is a group of volcanic cones 2 miles west and another group to the northwest of milepost 21. From these cones small flows of lava spread over areas of moderate extent at a time not very remote geologically, when the river valley was about 200 feet less deep than at present.

1This place should not be confounded with the ancient pueblo of Sandia, which lies 12 miles north of Albuquerque.

From the top of the mesa just beyond Sandia siding there are extensive views in every direction. About 15 miles to the east may be seen the bold western front of the Manzano Range, the high ridge which constitutes the southern extension of the Sandia Mountains and which is of similar structure. Far to the south is a prominent peak known as the Sierra Ladrones (lah-dro'nace, Spanish for thieves), consisting of a large but isolated mass of pre-Cambrian granite overlain by limestone of the Magdalena group. To the west is a wide region of high plateaus,2 out of which rises a very prominent peak, known as Mount Taylor, 11,389 feet high. It will be seen that the mesa or high plain of Santa Fe marl extends far to the north and south, partly filling a broad basin between the mountains. Originally its surface was a continuous plain, but the Rio Grande has cut a wide valley for itself 200 feet or more deep through the center of the plain, and now the river flows along the bottom of this valley, with a mesa or plateau of the "marls" forming cliffs or slopes on each side.

2 The region west of the Rio Grande, well known to geologists as "the plateau country," is a province which differs in its geography and geologic structure from most of the country to the east. The width of this plateau province is about 450 miles, its western margin being far to the west in Arizona. The predominant type of structure is widespread tabular surfaces or plateaus consisting of great sheets of the various sedimentary rocks lying nearly horizontal or presenting very wide dip slopes. Most of these plateaus extend across the country in huge steps with steep fronts and relatively level or smooth tops. The harder formations constitute the surface of the plateaus; the softer beds crop out in the slopes. There are many mesas or portions of these plateaus cut apart from the main area by erosion.

The rocks are sandstones, limestones, and shales of Cambrian to earlier Tertiary age, capped on some of the plateaus and mesas by thick sheets of lava. At many places high cones or necks of older volcanic rocks rise above the platforms, and widely scattered cinder cones mark the orifices of later eruptions. The province is markedly different in physiographic and structural characters from the Rocky Mountain country on the east and the region of deserts and long rugged ridges on the west.

This section of the country is one of great interest to the student of geology, for most of its relations are clearly exhibited, and therefore it presents more striking illustrations of geologic features than the adjoining provinces. It extends far to the north of the railway in New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, and for some distance to the south through central New Mexico. It is a region in which the beds constituting the earth's crust have been uplifted or depressed in broad waves and in places dislocated by faults or breaks, along which great blocks have moved bodily up or down on one side in relation to those on the other side. These peculiar structural conditions, due to a special kind of stresses in the earth's crust, are here localized, in a zone of relatively great extent, surrounded by regions in which there is much more intense tilting and breaking of the strata by folds and faults.

After crossing the low divide on the plateau beyond Sandia siding the train descends by a tortuous route to the valley of the Rio Puerco (pwair'co, Spanish for dirty). On the way it passes through many cuts in the Santa Fe marl that exhibit the characteristics of the deposits, which are mostly sands and loams, in some places consolidated into loose sandstones.

The Rio Puerco is a long stream draining the mesa country to the northwest and emptying into the Rio Grande some distance southeast of the crossing. Its valley is excavated mostly in soft beds of the Santa Fe marl and underlying shales (late Cretaceous). To the west is the Mesa Lucera (loo-say'ra), a plateau capped by a thick sheet of lava (basalt) lying on sandstones and shales. These strata dip steeply eastward in a low line of foothills extending along the east side of the mesa, but they are nearly level under the lava cap.

|

Rio Puerco. Elevation 5,049 feet. Kansas City 953 miles. |

A short distance south of Rio Puerco station there are several small knobs of volcanic rock rising above the wide valley bottom. West of Rio Puerco siding the old main line is paralleled for a few miles by a new track diverging, to the left for the westbound traffic and rejoining the old line a short distance beyond South Garcia (gar-see'ah) siding. From Rio Puerco to the Continental Divide, a distance of nearly 100 miles, the railroad ascends the valley of the San Jose (ho-say'), which empties into the Rio Puerco at Rio Puerco station.

Near milepost 39 is the termination of a narrow flow of lava, which appears to extend continuously from a source far up the valley. It widens in some places and narrows in others, and at intervals is covered in whole or in part by the alluvium or wash laid down by the stream.

|

Suwanee. Elevation 5,455 feet. Kansas City 968 miles. |

Suwanee station is on this lava sheet. A short distance to the southeast is a small mesa in which an older lava sheet caps buff sandstone (Dakota), shales (Morrison ?), and underlying gray and red massive sandstones (Zuni). Farther south is the precipitous edge of the lava sheet capping the high north end of the Mesa Lucera.1

1A mile north of Suwanee on the north side of the valley is a long ridge of moderate height capped by buff sandstones (Dakota) surmounting slopes of light greenish-gray clays probably equivalent to the Morrison formation. These clays are in turn underlain by a thick layer of massive buff sandstone, and in the bottom of the valley, not in view from the train, the top of a 50-foot bed of the underlying gypsum is exposed in a small area. Small faults which extend northward into the ridge at this place cut off the gypsum on the east and west.

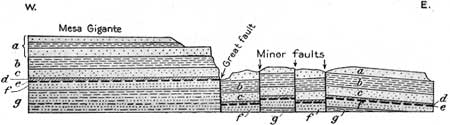

A fault of considerable magnitude is crossed a short distance west of Suwanee station and extends far north along the eastern margin of the high plateau known as Mesa Gigante (he-gahn'tay, Spanish for gigantic). This fault is a vertical break in the earth's crust along which the region to the west has been uplifted several hundred feet, bringing into view a thick mass of red beds. The relations are as shown in figure 17.

|

| FIGURE 17.—Section north of Suwanee, N. Mex., looking north, showing relations of faults. a, Dakota and overlying sandstones and shales; b, shale probably equivalent to the Morrison formation; c, buff massive sandstone; d, red sandstone; e, gypsum on thin-bedded limestone; f, massive pink sandstone (Wingate); g, red shales and sandstones. |

Where crossed by the railway this fault is covered by lava because the lava occupies a valley that was excavated long after the earth movement had taken place. North of the railway and west of the fault rises the Mesa Gigante, which is capped by massive gray to buff sandstones (Dakota and overlying Cretaceous). Below the sandstone cliffs are banks of shale or clay, in greater part of pale-greenish tint (probably equivalent to the Morrison formation), descending to long slopes and extensive cliffs of red sandstones and shales. These red cliffs are very conspicuous, notably from points near Armijo (ar-me'ho) siding and for some distance westward.

Three miles west of Suwanee there is an extinct hot spring or geyser cone not far south of the tracks. (See Pl. XIII; B, p. 75.) It contains a shallow crater 30 feet in diameter with walls of a hot-spring deposit, which also constitutes the low cone in which it is situated. The form of the bowl and cone indicates that at a time not very remote there was at this place a hot spring, or possibly a geyser, similar to those now active in the Yellowstone Park. South of Armijo siding a large valley from the south enters that of the San Jose. About 10 miles up this valley is a large recent volcanic cone, Cerro Verde (vair'day), and its lava flow appears to extend down to the San Jose Valley.

|

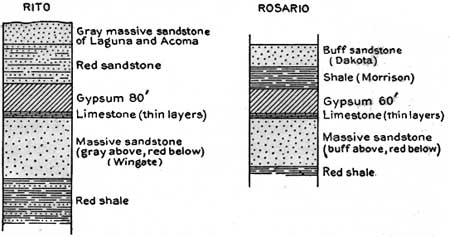

| FIGURE 18.—Sections showing relations of gypsum bed at Rito and near Rosario, N. Mex. |

|

Rito. Elevation 5,664 feet. Kansas City 981 miles. |

At Rito (ree'to) the railway passes a small pueblo (El Rito) of Laguna Indians, built on a low lava-capped plateau a short distance south of the railway. There are now only a few Indians at this place, as those living higher up the valley cut off the water during the irrigating season. These Indians subsist by raising sheep and goats and cultivating small crops.

South of Rito there is a high mesa of red and buff sandstone (Zuni) extending far to the south. To the north is a high cliff capped by bright-red sandstones, at the base of which is the outcrop of a great deposit of pure-white gypsum, 50 feet or more thick. As shown in Plate XIV, B (p. 96), it extends along the north side of the track for some distance. It is one of the most prominent exposures of gypsum known, rivaling the one east of Rosario station (see p. 82) and apparently of the same age. Figure 18 is introduced to show the succession of rocks in which the gypsum occurs at both places. This bed of gypsum crops out at several points in the region between Rosario and Rito with the same relations to adjoining rocks, so that there is no doubt as to its continuity. It is the same deposit which is exposed north of Suwanee, as shown in figure 17. It has been removed by erosion over wide areas where the rocks are uplifted, but, on the other hand, it underlies a district of great extent in which it has not been sufficiently uplifted to be subjected to erosion.1

1 The origin of gypsum deposits of this character is a problem of considerable interest, for the precise conditions of deposition are not known. It is believed that the gypsum was deposited during the evaporation of an inland sea that probably occupied a region of considerable extent in the central United States during later Carboniferous and early Mesozoic time. The thickness of the deposit together with its freedom from admixture with the sand and clays which constitute the rocks overlying and underlying it is remarkable, doubtless indicating that the area of deposition was remote from streams that could bring mud and sand into the sea. For this reason it is believed that the deposit was laid down at a time of scanty rainfall, when the waters of the sea were evaporating rapidly. Waters of this kind were also very salty, but in the course of their evaporation the gypsum was first deposited and the salt later, as the drying up continued. However, no salt deposits have been discovered in connection with the gypsum in this portion of New Mexico. Very salty waters emerge from some of the lower strata of the underlying red beds at various points, indicating that deposition of salt went on during part of the general period, but most of this salt is in rocks that were laid down prior to the thick deposit of gypsum which is so conspicuous at Rito, Rosario, and other places.

The red sandstones overlying the gypsum at Rito, together with a thick body of overlying buff sandstone, probably represents the lower part of the Zuni sandstones. This buff, massive sandstone is conspicuous in the bluffs north and northeast of Suwanee (see fig. 17), as well as in extensive railway and stream cuts along the valley west of Rito, notably near Laguna station and for some distance west. The red sandstone becomes very thin northeast of Suwanee and it also thins toward the south.

West of Rito the San Jose Valley narrows considerably and the railway follows its very crooked course to Quirk siding. In this interval there are numerous exposures of the edge of the lava flow which ran down the San Jose Valley to and beyond Suwanee. Most of the lava is south of the railway in this vicinity; on the north side are bluffs of the buff Zuni sandstone above referred to. This sandstone is also exposed in deep railway cuts west of Quirk, where it is overlain by light-colored shales and clays that extend up to a thick succession of sandstones (Dakota and higher). In the high mesas a mile or two north of the railway these sandstones are capped by a sheet of older lava (basalt).

|

Laguna. Elevation 5,797 feet. Population 1,583.* Kansas City 988 miles. |

Laguna station is nearly a mile north of the Indian pueblo of Laguna, through which the railway passed prior to a recent change of course to diminish distance and grade. This pueblo is one of the most interesting and accessible along the Santa Fe Railway and is visited by many tourists, who find accommodations, if necessary, at the houses of some of the American residents of the small settlements adjoining the pueblo.

The Indians at this place are a branch of the Keresan tribe, to which the Acoma Indians also belong, but according to their own tradition they are of mixed stock from the older pueblos. Their town is a relatively new settlement, dating back to about 1697, when it was established with the name San Jose de 1a Laguna, by Gov. Cubero. The village is built on ledges of buff sandstone on the north bank of San Jose River, which the Indians at that time called the Cubero. This stream affords water for domestic use as well as for the irrigation of small areas of various kinds of crops on which the natives subsist. The Indians had a Spanish grant of over a quarter of a million acres, most of which, however, was desert land. Around their principal pueblo, Laguna, they had many small villages, in which they lived during the summer. Of late years they have occupied some of these villages (Paquate, Negra, Encino, and Casa Blanca) permanently. About 1,800 Indians live in or near Laguna.

On both sides of the valley of San Jose River at Laguna, and along the branch canyons from the north and south, are high mesas with cliffs of sandstone. The beds lie nearly horizontal. The mesas are capped by gray to buff sandstones (Dakota and younger), while the lower cliffs are of massive buff Zuni sandstone. In the intermediate slopes there are extensive exposures of the pale greenish-gray clays, as in other sections east, which extend along the sides of the valley for some distance west beyond Cubero (koo-bay'ro) siding.

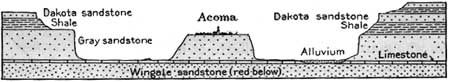

A short distance southwest of Laguna there comes in from the south a large valley, which heads in the vicinity of Acoma, one of the most remarkable Indian pueblos in the Southwest. As shown in Plate XV (p., 97), this place is built on top of a high, isolated mesa with precipitous walls of gray sandstone (see fig. 19) and has been an object of great interest to travelers ever since the first visit of Coronado. It is notable as the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in the United States. Unlike most of the other pueblo villages, Acoma is recorded in the early chronicles as the home of a people feared by the residents of the whole country around as robbers and warriors. Its location upon a precipitous white rock (Akome, "people of the white rock") rendered it well-nigh impregnable to native enemies as well as to Spanish conquerors, for the only means of approaching it was by climbing up an easily guarded cleft in the rock. However, one of the Spanish expeditions, with 70 men, succeeded in killing 1,500 of these Indians—half their total number—in a three-day battle in 1599. The entrance and stairway in use now are the same that were described by Alvarado on his visit with Coronado's expedition in 1540. The height of the mesa is 350 feet. The Acoma people are expert makers of pottery, as are also the Laguna Indians.

|

| FIGURE 19.—Sketch section through Acoma, N. Mex., looking south. |

A short distance north of Acoma is the famous Mesa Encantada (enchanted mesa), shown in Plate XIV, A, on which was located, according to the tradition of the Acomas, their prehistoric village of Katzimo.

|

|

PLATE XIV.—A (top), MESA ENCANTADA. N. MEX.,

SEEN FROM THE NORTH. The mesa is about 350 feet high, and its width

is about one-third its length. The rock is buff massive sandstone of the

lower part of the Zuni formation. B (bottom), BED OF GYPSUM AT RITO, N. MEX. View northward. The bed is 50 feet thick and lies under red sandstone opposite the Indian pueblo just north of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway. The base of the gypsum bed (A) rests on limestone. |

|

| PLATE XV.—PUEBLO OF ACOMA, N. MEX. Church in center. The pueblo stands on a high mesa of massive buff sandstone of the lower part of the Zuni formation. Shows wind-blown sand sloping upward to the top of the mesa. |

Acoma is easily reached from Laguna by a drive of 18 miles, for which a team and Indian driver can usually be obtained at Laguna. It will be found that the Indians of Acoma are rather indifferent to the desire of the tourist to see the sights of the place unless some remuneration is offered. The large church, built mainly of slabs of rock is still in excellent condition, although it was built about 1699. The New Mexico building at the Panama-California Exposition at San Diego is patterned after this church, with the portico modified after the church at Cochiti. The population in 1902 was 566.

West from Laguna the railway continues to ascend the valley of The San Jose. This stream for part of the year furnishes water for a small amount of irrigation, mostly by the Indians of the Acoma tribe, who maintain summer villages at different places.

|

Cubero. Elevation 5,929 feet. Population 515.* Kansas City 993 miles. |

At Cubero, now a small Mexican village, there was formerly a pueblo of San Felipe Indians, who now live near Santo Domingo. The name Cubero is that of the Spanish governor in office at the end of the seventeenth century. The real town of Cubero, a Mexican settlement, is 8 miles to the northeast. There are many Penitentes in these villages. About 2 miles beyond Cubero, near milepost 74, there is a view up the valley in which the pueblo of Acoma and the Mesa Encantada are situated, about 10 miles to the south in an air line. On both sides of the San Jose Valley are high walls of the Dakota and Mancos sandstones, which lie nearly horizontal, so that the railway rises to higher and higher beds as it ascends the valley.

Near milepost 77, 5 miles west of Cubero siding, there is to the north a fine view of Mount Taylor, a huge cone standing on a high plateau of sandstone and lava. It was named for President Zachary Taylor, but this name has not entirely displaced the local name, Sierra San Mateo. This mountain is an isolated mass consisting largely of gray lava (andesite) and represents an eruption of considerable antiquity, much older than the sheets of black lava (basalt) which cap the plateaus or mesas along the north side of the valley. Since these early lava outflows the valleys have been-cut to their present depths of 1,500 to 2,000 feet and a considerable area of the plateaus has also been removed, as shown in figure 20. Mount Taylor is held in great veneration by the Pueblo Indians, who call it the "mother of the rain." In the spring a party of them usually goes to its top for sacred dances to invoke the rain god for a plentiful harvest.

|

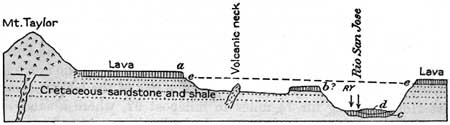

| FIGURE 20.—Sketch section showing relations of lava sheets near Mount Taylor, N., Mex. a, b, c, d Four successive lava flows later than flow in Mount Taylor; e—e, former surface of plateau before valley of San Jose River was excavated. |

A short distance south of the track near milepost 77 is the small pueblo of Acomita, which belongs to the Acoma Indians and serves as a home for about 200 of them during the summer when they are cultivating the fields in the bottom of the valley. There is a United States Indian school here and a good road southward to Acoma.

|

Alaska. Elevation 6,041 feet. Kansas City 999 miles. McCartys. Elevation 6,041 feet. Kansas City 1,002 miles. |

Mount Taylor is again visible from Alaska siding and west from that place for a mile or two. The platform from which it rises is covered by a sheet of black lava (basalt) capping cliffs and long slopes of the later Cretaceous sandstones. Far to the south rise extensive high plateaus occupying the region west of Acoma.

Halfway between mileposts 80 and 81, the lava sheet in the bottom of the valley is plainly visible. The lava flowed out of vents in the region to the west at a time much later than that of the eruption of the lava sheet which caps the mesa that extends along the north side of the valley from Laguna westward. At milepost 81 there is an exceptionally good view of Mount Taylor.

McCartys is a trading center for ranches and the Indians in the San Jose Valley and adjoining region. At Acoma siding (see sheet 15, p., 104), 2-1/2 miles west of McCartys, there is an Indian village of moderate size on the south side of the valley, used as a summer home by a some of the Acoma Indians.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/613/sec14.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2006