|

Geological Survey Bulletin 613

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C. The Santa Fe Route |

ITINERARY

A short distance west of the main Petrified Forest, at the head of a small valley which joins the valley of Little Colorado River at Woodruff (see sheet 17, p. 112), is a group of prehistoric pueblo ruins which have been thought to be of Zuni origin.

|

|

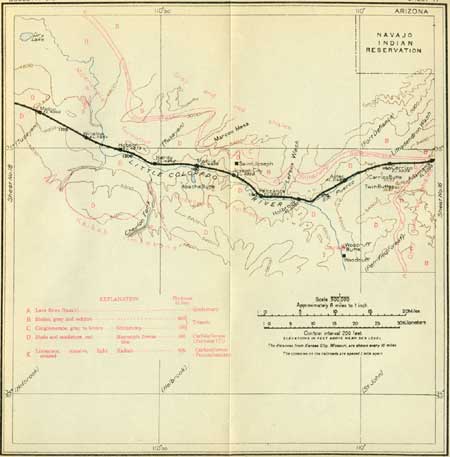

SHEET No. 17 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

A boring was made in the red shale at Adamana to obtain a water supply, but the water, though found with sufficient head to afford a flow, was too salty for use. This condition is almost universal in the red shale of the Moencopie formation, which was penetrated in the boring.

West of Adamana the railway continues down the valley of the Rio Puerco, which widens somewhat because of the softness of the red Moencopie shale, in which it is excavated. The conglomerate (Shinarump) which lies next above this shale, caps slopes and buttes some distance to the north and south.

The beds lie almost flat, so that the railway in descending the valley crosses successively older and lower beds.

|

Aztec. Elevation 5,148 feet. Kansas City 1,167 miles. |

A short distance beyond milepost 251 the Rio Puerco empties into Little Colorado River, which flows from the south but turns almost due west after its junction with the Puerco. From this place the railway continues along the north bank of the Little Colorado nearly to Winslow. The valley is wide and contains extensive flats of alluvium, with more or less loose wind-blown sand. In a few places there are ranches where the river water is utilized for irrigation.

|

Holbrook. Elevation 5,080 feet. Population 609.* Kansas City 1,174 miles. |

Holbrook is sustained largely by scattered ranches in the surrounding country. One of the principal industries of the region is the raising of stock, sheep, and goats, and it is reported that 200,000 pounds of wool were shipped from Holbrook in 1914. There is considerable trade with the Indians here, for the Navajo Indian Reservation is only a few miles northeast and the Hopi country begins not far to the northwest. Holbrook is also an outlet for considerable travel coming down the valley of the Little Colorado from St. John and other places farther south.

Holbrook is situated on the red shales and sandstones of the Moencopie formation. The beds dip very gently to the north, and within a few miles in that direction the red rocks pass under the Shinarump conglomerate, the outcrop of which is marked by low cliffs and numerous buttes. The red rocks of the Moencopie formation are prominent all along the valley from Holbrook to Winslow, cropping out in many low cliffs and mesas. A few miles north of the valley are wide areas of badlands, as shown in Plate XXII. These are developed by erosion in the soft sandy clays in the formation overlying the Shinarump conglomerate.

|

| PLATE XXII.—BADLANDS NORTH OF HOLBROOK, ARIZ. View southward. The material is sandy clay. Lava-capped buttes of red sandstone in distance at right. |

North of Joseph City siding is the Mormon settlement of St. Joseph, where crops are raised by irrigation from the Little Colorado. To the south is an area of 800 acres irrigated from deep wells. These places are conspicuous green oases in a region where the gray desert aspect prevails. Along the Little Colorado Valley at intervals are cottonwood trees, some of them large and clustered in groves of considerable extent.

|

Manila. Elevation 4,956 feet. Kansas City 1,190 miles. |

As the Little Colorado Valley widens near Manila and Hardy sidings, there appear to the north many mesas and slender pinnacles of igneous rock which rise high above the general plain. Far to the north in the Navajo Reservation may be discerned the cliff at the edge of an extensive mesa, which contains a large coal field that has not yet been developed.

About 2 miles east of Winslow the railway crosses the Little Colorado, which here makes an abrupt turn to the north. A few miles farther west the river bends to the northwest to join Colorado River in the Grand Canyon at a point about 100 miles northwest of Winslow. The original name of this stream was Rio Lino (that is, Flax River), a distinctive name which would be preferable to the present name.

|

Winslow. Elevation 4,854 feet. Population 2,381. Kansas City 1,207 miles. |

Winslow is a railway division point where many trains stop for meals. It is the headquarters for a large surrounding stock country and an important center of trade with Hopi and Navajo Indians (see Pl. XXIII) in the reservations not far north. Near Winslow are the ruins of Homolobi Pueblo, claimed by the Hopis to be the home of their ancestors before the tribe had to flee to the high cliffs far to the north to be safe from their enemies.

|

|

PLATE XXIII.— (top), NAVAJO INDIANS VISITING

THE HOPI INDIANS AT ORAIBI, NORTH OF WINSLOW, ARIZ. Photograph

furnished by Santa Fe Railway Co. B (bottom), AN EVENING WITH NAVAJO INDIANS ABOUT THE CAMP FIRE, NORTH-CENTRAL ARIZONA. |

Winslow is at the south end of the Painted Desert, a district of undulating plains and bright-colored cliffs, which extends far northward into Utah. The Painted Desert lies between the canyons of Little Colorado and Colorado rivers on the west and the buttes and plateaus of the highlands on the east. Its width in general is about 40 miles, comprising the outcrop of sandstones and shales that are mostly of Triassic age.

Except in the two rivers there is no running water on the Painted Desert, and springs and water holes are far apart and of small volume.

The Hopi Indian villages of Oraibi (Pl. XXIV), Walpi, Schimopavi, Shipauiluvi, Mishonginivi, Sichomivi, and Hano are picturesquely built on the cliffs which project from a high plateau of sandstone into the western margin of the Painted Desert, about 60 miles north of Winslow. They are in a reservation about 50 by 70 miles in extent which the Government has set aside for the Hopis.1

1The name Hopi means "peaceful ones," and the (to them) very unacceptable word Moki, sometimes applied to them by other Indians, is derisive, meaning "dead ones." They are Shoshonean in language, but are a composite of various stocks. They are intelligent, thrifty, tractable, hospitable, and frugal. Their lives are full of toil to raise crops in an arid region, and full of prayers and religious ceremonies largely intended to persuade their gods to send water for the crops. They are monogamists and faithful to marriage ties. Murder is unknown among them, theft rare, and lying deprecated. They now number about 2,100, having diminished considerably in the last 50 years. Escalante reported nearly 7,500 in 1774 and only 798 were recorded in 1780, more than 6,000 having died of disease. A very large proportion of them have trachoma.

|

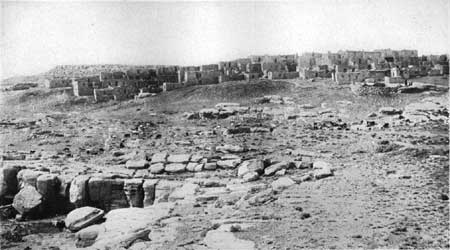

| PLATE XXIV.—ORAIBI, A HOPI VILLAGE ON THE SANDSTONE PROMONTORIES EAST OF THE PAINTED DESERT, NORTH OF HOLBROOK, ARIZ. |

The first white men to visit the Hopi Indians were the members of a party under Pedro de Tovar (toe-vahr'), sent by Coronado. At that time seven villages constituted the province of Tusayan (too-sah'yan), as it was subsequently known. These were in the neighborhood of the present Hopi villages, but the Hopi Indians claim as ancestral homes ruins found as far away as Verde River and the Rio Grande. The present Hopi villages are the objective point of many tourists, especially on the occasion of the far-famed snake dance, which occurs in August.

For centuries the Pueblo people of this arid climate have been developing the Indian maize, a peculiar corn with wonderful drought-resisting properties. It is planted from 6 to 12 inches below the surface, the depth depending on the condition of the soil, and the long single root goes deep to gather the scant moisture of the sandy soil. A stem also extends straight to the surface and there concentrates its energy in seed development, with only a few straggly leaves from its short stalk. Consequently a field of maize presents a very poor appearance compared with an eastern cornfield. However, if there is a little rainfall at the critical part of the growing season, it yields a fair crop.

The climate of this region is typical of much of the higher portions of Arizona, with its scanty rainfall and large percentage of cloudless days (about 60 per cent). The days are dry and hot in summer, but the night temperatures are usually 40° cooler. At Holbrook the mean annual precipitation is 9.16 inches and the mean annual temperature 54.2°. At Winslow the precipitation is 7 inches and the temperature 55°, while Flagstaff, on the plateau 2,000 feet higher, has nearly 24 inches of rainfall and a much lower temperature, 44.7°.

Winslow is on the red sandstones and shales of the Moencopie formation. To the northeast these rocks pass under the Shinarump conglomerate, the outcrop of which extends across the country in low bluffs that may be observed 6 miles northeast of Winslow. Beyond this conglomerate is a wide area occupied by a thick succession of light-colored shales, and in the distance are scattered buttes of still higher red sandstone (the Wingate), capped by small remnants of old lava sheets. Some of these lava buttes are very prominent features in the landscape far to the northeast of Winslow. The Moencopie formation extends northwest of Winslow and Moqui siding in a broad belt down the valley of the Little Colorado, which finally cuts down into the underlying limestone (the Kaibab). West of Winslow the train leaves this valley and climbs gradually to the Arizona Plateau. This extensive table-land rises continuously to Flagstaff and beyond and also northwestward to the edge of the Grand Canyon. The greater part of its surface consists of bare limestone (the Kaibab), which dips at a low but nearly uniform angle to the east and southeast. At Winslow this limestone is some distance beneath the surface, under the red sandstones of the Moencopie formation, but as it rises to the west at a somewhat more rapid rate than the ascent of the railway it finally reaches the surface. It first appears at a point a short distance beyond Dennison siding (see sheet 18, p. 120), but for several miles, to and beyond Sunshine siding, numerous outlying masses of the basal red sandstone of the Moencopie remain on it. Just south of Sunshine this sandstone has been quarried to a considerable extent for building stone.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/613/sec17.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2006