|

Geological Survey Bulletin 613

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C. The Santa Fe Route |

ITINERARY

|

Sunshine. Elevation 5,341 feet. Kansas City 1,227 miles. |

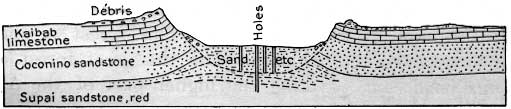

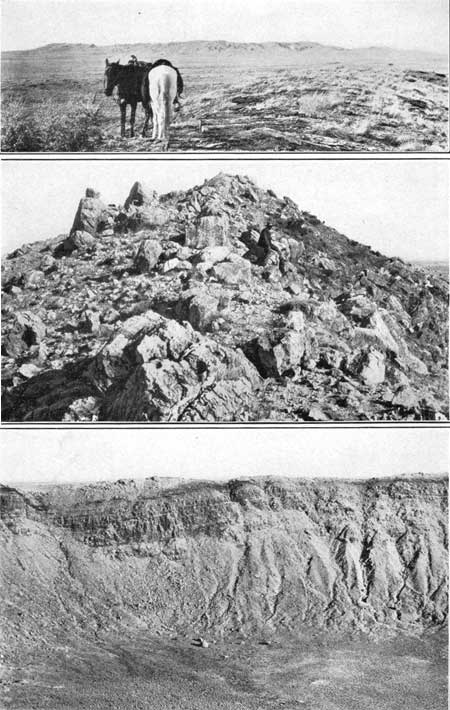

About 10 miles south of Sunshine is Crater Mound, long known as Coon Butte and for a while as Meteorite Mountain, perhaps the most mysterious geologic feature in the West. Viewed from the railway, it appears as a low ridge (see Pl. XXV, A), but on near approach this ridge is found to be circular and to inclose a great hole 4,000 feet in diameter and 600 feet deep.1 (See PL. XXV, C.) The encircling ridge is from 100 to 150 feet high and consists of loose fragments of rock and sand blown out of the hole. (See Pl. XXV, B.) The beds of rock in the walls of the hole are Kaibab limestone at the top and Coconino sandstone below, both more or less upturned near the hole and in part considerably shattered. The relations are shown in figure 23. The best view of Crater Mound is obtained from points near milepost 309.

1The cause of this great hole in the ground has not been ascertained. Several geologists believe that it was made by the impact of a great meteor, a view suggested by the occurrence of many small masses of meteoric iron in the vicinity, as well as elsewhere in the surrounding country, but a mining company organized to find and work the large mass supposed to be buried in the hole failed to obtain any evidences of its existence. Many test borings and a shaft were sunk 200 feet into the detritus in the floor of the hole, and a 1,020-foot hole found that the underlying sandstones are not disturbed. Moreover, a detailed survey with a magnetic needle, hung, to swing vertically, failed to show any evidence of the presence of a body of metallic iron.

Another suggestion is that the hole is due to an explosion of steam from volcanic sources below, accumulating in the pores of the sandstone and finally reaching the limit of tension. This would account for the broken sandstone and limestone constituting the encircling rim and for the upturned edges of the strata, which doubtless would bend upward somewhat before they broke. The large amount of fine sand produced would result from the violence of the explosion of steam contained in the interstices of the sandstone. Such an explosion might not greatly disturb the underlying Supai sandstone if the zone of explosion were in the overlying Coconino sandstone, which is much the more porous material. The locality is in the midst of a region of former great volcanic activity, for although there are no lava flows in the immediate vicinity of the hole there are large outflows and vents not many miles away in all directions. A somewhat similar hole or crater holds the Zuni Salt Lake, 115 miles to the southeast. From its center rise two very recent cinder cones, one with a deep crater in its top. The rim surrounding the big hole consists of a mixture of volcanic ejecta and fragments of rocks from far below the surface.

FIGURE 23.—Generalized section across Crater Mound, Ariz.

|

|

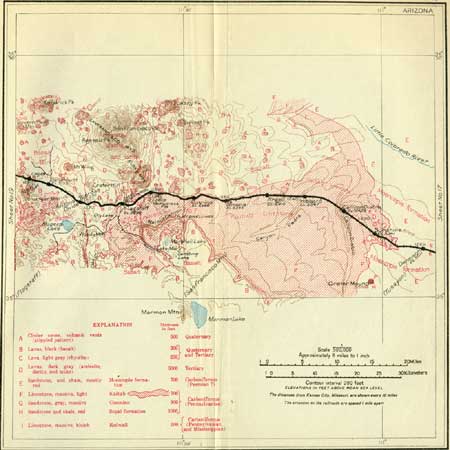

SHEET No. 18 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

|

PLATE XXV.—A (top), VIEW OF CRATER MOUND,

ARIZ. FROM THE SOUTHWEST, SHOWING ENCIRCLING RIM. B (center), NEAR VIEW OF RIM OF CRATER MOUND. C (bottom), VIEW ACROSS THE CRATER OF CRATER MOUND, SHOWING UPTURNED LIMESTONE BEDS IN ITS WALLS. |

West of Sunshine there is a nearly continuous exposure of the Kaibab limestone to Flagstaff, and this rock also extends far to the north, south, and southwest. As the slope is ascended northwest of Sunshine siding there is a fine view of the Painted Desert far to the northeast, and beyond it may be seen dimly the high promontories or plateaus on which the Hopi villages are built.

|

Canyon Diablo. Elevation 5,429 feet. Kansas City 1,233 miles. |

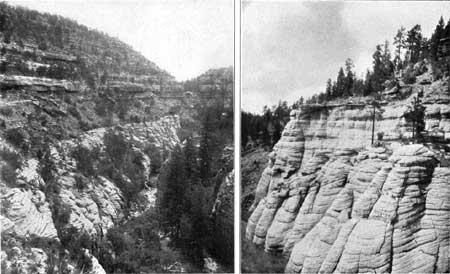

A short distance beyond Canyon Diablo station the railroad crosses the canyon on a long steel bridge, affording a very good view of this interesting feature. (See Pl. XXVI.) The canyon is steep walled, about 225 feet deep, 550 feet wide, and entirely in the Kaibab limestone. The beds, which are thick and massive, are nearly horizontal and appear as huge steps descending to the bottom of the canyon.

|

| PLATE XXVI.—CANYON DIABLO, ARIZ. View up the canyon at a point between Winslow and Flagstaff. The steplike ledges of Kaibab limestone at the right lie nearly horizontal. Photograph taken many years ago. Shows old-time train of Atlantic & Pacific Railroad, the predecessor of the Santa Fe Railway. |

Just beyond Hibbard siding is another canyon known as Canyon Padre (pah'dray), not as deep as Canyon Diablo, but of similar shape. Both of them are excellent illustrations of the results of erosion in hard limestone by streams of considerable slope. The flow is transient, for only at times of rainfall is there any water in them, but then the current is swift and the water carries much sand, which vigorously cuts away the limestone.

West of Canyon Padre there may be seen ahead and to the north many knobs and ridges rising above the plateau surface. They consist of volcanic rocks which cover a wide area to the northwest and culminate in the high peaks of the San Francisco Mountains, 25 miles away, which are prominently in view for many miles along the railway.

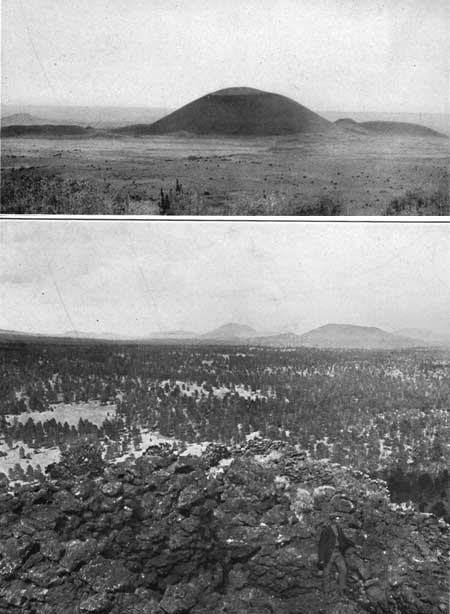

At milepost 320 there is a cinder cone a short distance north of the railway, with a lava flow extending from its base to the east and another to the south, the latter reaching nearly to the track. The cone is remarkably symmetrical and fresh looking, and the lava flow is closely similar to that which is exposed near Grant and Horace, 220 miles farther east. A short distance north of the cone is the southern margin of a wide area of lava (basalt), which extends far to the north as well as to the northeast and northwest. On its rugged surface are many cinder cones which are visible more or less distinctly from the train. (See Pl. XXVII.)

|

|

PLATE XXVII.—A (top), RECENT CINDER CONE

EAST OF SAN FRANCISCO MOUNTAINS, NORTH OF WINONA, ARIZ. Rises above

broad sheets of lava and marks a vent. B (bottom), CINDER CONES IN COCONINO FOREST EAST OF SAN FRANCISCO MOUNTAINS, ARIZ. View from edge of a recent cone showing large fragments of lava and cinder. |

Between mileposts 319 and 320 is a signboard reading "Eastern boundary Coconino National Forest." This forest is one of two Government reservations which include the great forest of yellow pine (Pinus ponderosa) covering the higher part of the Arizona or Coconino Plateau.1

1These great forests extend northwestward to the Grand Canyon, westward to and beyond Williams, and southward to the southern margin of the plateau. They include about 1,317,000 acres of western yellow pine. In parts of the forest and in a broad zone around its margin are junipers (Juniperus occidentalis var. monosperma) and piñon (Pinus edulis). The pines grow on the limestone and volcanic rocks, and the forest limits are determined by the moisture, which in turn is largely controlled by the altitude. Accordingly the pine growth is nearly all in the area higher than 6,200 feet, for at lower altitudes than this the precipitation is insufficient; in fact, even in some of the western portions of the high plateau, where the altitude is slightly above this amount, the rainfall is too scanty or the soil too dry to support a forest. The yellow pine gives place to other trees, mainly firs, spruce, and aspen, above 8,500 to 9,000 feet, and the forest ceases at an altitude of 12,000 feet on the San Francisco Mountains.

The investigations of the Geological Survey and the Forest Service on the relation of forests to water supply and soil waste indicate that forests in mountainous districts conserve the precipitation for stream flow and increase the underground storage of water. The trees break the violence of the rain, retard snow melting, and increase absorption by the soil, all of which diminish erosion of the surface and rapidity and volume of run-off. Underground seepage is increased, so that a steady flow is maintained in springs and streams, and less silt is removed, hence there is less to obstruct the stream beds.

Fires have ravaged many parts of the forests, and one of the principal functions of the Forest Service is to prevent or extinguish them. Lookouts are maintained on high points. Lightning starts fires and destroys many trees that do not ignite. It has been estimated that 40,000 trees were struck in three years in the high plateau province of Arizona and adjoining regions.

As the limestone plateau is ascended, the first trees observed are stunted junipers and piñons; these rapidly increase in size and abundance as the higher altitudes are attained, a feature especially noticeable between Angell and Winona sidings.

|

Angell. Elevation 5,910 feet. Kansas City 1,243 miles. |

At Angell and for several miles west many cinder cones are visible on the widespread lava sheet which begins a short distance north of that siding. Most of these cones are from 150 to 250 feet high. They consist of piles of loose, dark volcanic cinder or pumice which varies from pieces 2 inches in diameter to fine sand. The deposit includes volcanic bombs, rounded masses of more compact lava, which were ejected from volcanic vents. This region of lava occupies an area about 15 miles wide from north to south and 70 miles long from east to west, with the San Francisco Mountains near the center. It has been designated the San Franciscan volcanic field.1

1Three general periods of volcanic activity are indicated in this field. First came a widespread outflow of basalt, which issued from numerous cracks in the limestone and underlying strata in a very fluid condition and spread widely over the gently sloping surface of the plateau. In the second period occurred the eruption of several large masses of more viscous lavas (andesite, dacite, and latite) now constituting San Francisco Mountain, Kendrick Peak, Elden Mountain, O'Leary Peak, and other high summits. These lavas, being less fluid than the earlier basalt, piled up and in part arched up on it in high mounds of relatively small extent. As these rocks are hard and massive they give rise to very prominent topographic features. It is probable that there was a considerable interval of time between the first basalt eruptions and the outflows of less fluid lavas, but apparently all of them were extruded late in Tertiary time. There are also bodies of intruded rhyolite which apparently cut across the earlier basalt at several localities, notably in Sitgreaves Peak, Government Mountain, and O'Leary Peak. This rhyolite is a light-gray or nearly white rock, usually breaking into thin slabs.

In the third period of eruption in the San Francisco volcanic field occurred an extensive outflow of black lava (basalt) similar to the first. It came out of numerous cracks and other orifices, mostly within the area of the earlier lava sheets. The lava at many localities ran down valleys which had been eroded in the earlier lava sheets or the underlying limestone in the interval between the periods of eruption. Most of this later lava is exceedingly fresh in appearance, similar to that occupying the San Jose Valley at Grant and McCartys, N. Mex. which is described on pages 97-98.

At many of the vents the cessation of lava flow was followed by an outburst of cinders and ash. This material was thrown up into the air for some distance and, settling back about the vent, formed a cone, as a rule with a central crater. The building of these cinder cones usually marked the last stage of activity of the crater, but in some places a later gush of lava was poured out from the side or base of the cone. The lava contained a vast volume of steam, for much of it is highly porous, owing to the expansion of the steam in the cooling rock as it flowed out over the surface. The cinder consists of lava filled with small steam holes, so that most of it is completely porous or pumaceous. In the cinder cones are usually included masses of compact lava probably thrown out as bombs. These vary in form from perfectly round balls to elongated and irregular shapes such as might be expected in molten material ejected from a vent. Their surface is smooth. In places there are flattened masses of lava several square yards in extent, in part twisted around some of the cinder in which they are inclosed. Several of the cinder cones doubtless date back to the earlier basalt eruption, but most of them appear to belong to the last period.

There are several hundred cinder cones in the field, presenting a great variety in size, height, and stage of preservation. Many have deep craters or hopper-shaped cavities at the top. The distribution of most of them is shown in figure 24, which also shows the approximate extent of the lava fields. Excellent views of cinder cones may be had to the northwest from mileposts 321, 324, and 325, and at Winona there are two small cones a short distance south of the track.

|

| FIGURE 24.—Map of the lava field in the San Francisco Mountain district, Ariz., showing distribution of cinder cones marking vents of eruption. (After H. H. Robinson.) |

At milepost 326 the railway reaches the south edge of the great basalt flow. It continues along this edge but is built mostly on the underlying limestone almost as far as Flagstaff. There is a cut in the basalt on the north side of the track at milepost 326. At milepost 328, just east of Winona, the railway enters the basalt area, on which it continues for about a mile, and at many points in the next few miles the edge of the basalt is a short distance north of the tracks.

Between Winona and Cosnino sidings the San Francisco Mountains are in plain sight to the northwest, and many minor volcanic peaks are also visible to the north. In greater part the railroad is built on the Kaibab limestone, which is well exposed in several cuts.

|

Cosnino. Elevation 6,466 feet. Kansas City 1,254 miles. |

At Cosnino the pines begin to be numerous and of large size, and a short distance to the west, at an altitude of about 6,300 feet, the traveler enters the great pine forest which extends continuously to Williams. Cosnino is a name formerly applied to the Havasupai tribe of Yuman Indians, who live in Cataract Canyon, near Grand Canyon. They once occupied permanent villages on the Arizona Plateau but were forced to abandon them owing to the hostility of tribes living farther east.

Two miles beyond Cosnino the train approaches a large cinder cone which extends for about a mile along the north side of the track, and halfway between mileposts 336 and 337 there are cuts exposing some features of the cinder deposits constituting this cone. Most of the material is fine grained but there are many included masses consisting of cinder agglomerated together and numerous bombs.

One of the most notable examples of a recent cinder cone is Sunset Peak, which is visible 10 miles to the north from the vicinity of milepost 337. This cone is 300 feet high and has steep slopes of loose cinders, part of which are of a bright-red color, giving the cone the appearance of being illumined by the setting sun. The crater at the top is 80 feet deep and 200 feet in diameter, but the original orifice under this depression is covered by the loose material sliding down the steep slopes.

Halfway between mileposts 338 and 339 is a red cinder cone 200 feet high, half a mile north of the railway, with a small tongue of lava extending from its base southward to a point a short distance east of milepost 339.

|

Cliffs. Elevation 6,829 feet. Kansas City 1,260 miles. |

At Cliffs the train runs near the south edge of Elden Mountain, a prominent mass of dark-colored dacite of the second period of volcanic activity. The lava is in heavy beds presenting an arched appearance, suggesting strongly that the lava was poured out in thick viscous layers which were finally bent upward by the pushing of some central force at or toward the end of the period of eruption. That this range has been considerably upthrust is further indicated by the presence of some large uplifted masses of the sedimentary rocks of the plateau along its east side. In this uplift are exposed the Redwall limestone, the red sandstone of the Supai formation, the Coconino sandstone, and the Kaibab limestone, all dipping steeply eastward with the relations shown in figure 25.

|

| FIGURE 25.—Section of Elden Mountain, east of Flagstaff, Ariz., showing relations of beds upturned on its east side, a, Limestone (Kaibab) b, gray sandstone (Coconino); c, red sandstone (Supai); d, limestone (Redwall); e, igneous rock. (After H. H. Robinson.) |

Half a mile south of Cliffs there are some remarkable sink holes in the bottom of the valley, known as the Bottomless Pits (Pl. XXVIII). They form the entrance to a cavern in the Kaibab limestone made by the solvent action of water on the limestone in its passage underground through joints and fissures to outlets in the depths of Walnut Canyon, a few miles south.

|

| PLATE XXVIII.—BOTTOMLESS PITS SOUTH OF CLIFFS, EIGHT MILES SOUTHEAST OF FLAGSTAFF, ARIZ. The water passes into a sink or cave formed by the solution of Kaibab limestone. |

Along the walls of this canyon, 5 miles southeast of Cliffs, is a known group of cliff dwellings, shown in Plate XXIX, A. They belonged to Indians of a race that existed many centuries ago and live hidden in these canyons. They built stone houses under the overhanging ledges of limestone a hundred feet above the stream bed. These ledges are due to the variations in hardness of the beds of Kaibab limestone, the soft beds weathering away, leaving the hard beds in the form of ledges. One soft bed in particular which has weathered out along both sides of Walnut Canyon for some distance gave the Indians an excellent site for many houses of this character. It has been estimated that 1,000 persons lived in these cliff dwellings, which are easily accessible by an excellent carriage road from Flagstaff, the principal town of this region.

|

|

PLATE XXIX.—A (left), CLIFF DWELLINGS IN

WALNUT CANYON, SOUTHEAST OF FLAGSTAFF, ARIZ. Ruins of houses are under

overhanging cliff of Kaibab limestone. B (right), CROSS-BEDDING IN COCONINO SANDSTONE IN WALNUT CANYON, ARIZ. The cross-bedding, which is diagonal to the regular bedding, was produced by strong currents that varied in direction as they deposited the sand. |

A short distance beyond milepost 342 the railway passes along the north edge of a small lava field occupying a valley, and in slopes north of the track is an outlying mass of the red Moencopie sandstone, which extends for a mile and a half, or nearly to Flagstaff. The sandstone is overlain by an older sheet of lava (basalt), which caps the mesa northeast of Flagstaff. This sandstone has been extensively quarried a few rods north of milepost 343, furnishing a beautiful red stone which has been used at many places in the West, notably in the Brown Palace Hotel, Denver, and the city hall at Los Angeles.

|

Flagstaff. Elevation 6,896 feet. Population 1,633. Kansas City 1,265 miles. |

Flagstaff is a growing city, largely sustained by the lumbering business and surrounding ranches. It was named from a pole set by a party of immigrants who camped near by and celebrated the Fourth of July. Formerly it was the point of departure for stages for the Grand Canyon, 60 miles to the northwest, but this service has been mostly superseded by the railway line from Williams. An excellent road, however, has been built to the canyon. It passes around the east side of the Elden and San Francisco mountains to a point near Sunset Peak and thence north across the volcanic field and plateau, reaching the edge of the canyon at Grandview. When conditions are favorable this trip can be made in five or six hours by automobile.

There are large lumber mills at Flagstaff deriving much of their supply from the pine timber of the Coconino National Forest, which they purchase "on the stump" from the Government. In accordance with the regulations of the Forest Service, only the mature trees are cut. The average age of old pine trees in the Coconino Forest has been determined to be 348 years, but some have been found as old as 520 years, dating back a century before the first visit of Columbus to America. Recent investigations made to ascertain rainfall conditions in the past as indicated by variations in rings of growth in trees show marked changes in climate in alternating long cycles of drier and more rainy periods.

On the edge of the high mesa in the western part of Flagstaff is the Lowell Observatory, which is equipped with an especially fine telescope through which Dr. Percival Lowell and his assistants have made their famous observations on the planet Mars. The clear, steady air of this high altitude is particularly favorable for astronomical work.

The peaks of the San Francisco1 are prominent from Flagstaff, and the trip to their summit can easily be made on horseback from that place. The region from these mountains to Gila River was the domain of the Apaches (Pinal Coyote) until their final surrender through the efforts of Gen. Crook and Gen. Miles in 1886. At one time the San Francisco Mountains were the refuge of the Havasupai Indians, who fled there when driven from their home on the Little Colorado. These Indians are the only ones among the Yuman tribes who had a culture similar to that of the Pueblo people farther east. A number of ruins are ascribed to them as far south as the Rio Verde, in central Arizona, and the early name Cosnino, by which this tribe was known, has been applied to many features in this region. They now live in Cataract Canyon, 60 miles northwest of Williams.

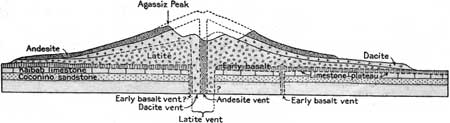

1The structure of these mountains is shown in figure 26. They consist of a thick pile of latite lying on a sheet of earlier basalt and overlain by flows of other lava, mainly dacite and andesite. These rocks appear to lie on the limestone platform of the plateau, but the beds may be upturned, and possibly some Moencopie sandstone may underlie the central mass of latite.

FIGURE 26.—Generalized section through the San Francisco Mountains, northeast of Flagstaff, Ariz., looking north. Dotted portion eroded; broken line hypothetical.

West of Flagstaff the train continues to climb up the plateau slope. In this vicinity the Kaibab limestone is mostly covered by lavas of various kinds, but its surface appears for a short distance in a depression just west of Flagstaff. For the first 5 miles west the railroad passes along the southern foot of a mesa consisting of a light-gray lava (latite), poured out over the surface in a thick mass during the second period of volcanic activity.

|

Riordan. Elevation 7,311 feet. Kansas City 1,272 miles. Bellemont. Elevation 7,132 feet. Population 692.* Kansas City 1,277 miles. |

Just east of Riordan siding, eight-tenths of a mile beyond milepost 350, the Arizona Divide is crossed at an altitude of 7,311 feet, the highest point reached by the railway on the plateau. At this place and westward to and beyond Williams the surface is dark lava (basalt) of somewhat irregular configuration, with many large cinder cones on every side.

Bellemont is in a wide "park" or open space in the forest, near the southern edge of one of the large lava flows. A short distance to the south, where the lava lies on limestone, there are copious springs of exceptionally good water. This water is derived from rain and melting snow on the surface of the lava. It percolates through the porous rock to the underlying limestone and flows along the surface of the limestone to its outcrop. It is pumped to the station and used on the railway. On a well-watered flat north of this station is probably the heaviest stand of timber in Arizona or New Mexico.

At Nevin siding, 2 miles west of Bellemont, a small cinder cone has afforded the railway company a supply of ballast which has been used on the tracks for many miles to the east and west. The pit, which is north of the siding, is large and presents an especially fine section through the cone. The principal working face, nearly 100 feet high, shows thick beds of cinders with large numbers of scattered bombs of various sizes and flattened masses of lava which have been thrown out bodily. The vent from which all this material was ejected has not been exposed by the excavations. As in many other cones, much of the material is red, owing to the oxidation of the iron which the lava contains. This oxidation develops more extensively in the cinder or bombs than in the solid basalt, for air and water, which facilitate the oxidation, have more complete access to material that is in the porous form.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/613/sec18.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2006