|

Geological Survey Bulletin 613

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C. The Santa Fe Route |

ITINERARY

The Aubrey Cliffs extend for many miles across the plateau region on both sides of the Grand Canyon. As explained above, they are caused by the western edge of the great sheet of limestone that caps the Arizona Plateau. The depression at their foot, here known as Aubrey Valley, is followed by the railway for some distance to the northwest, past Audley and Pica sidings. The floor of the valley consists in part of the lower red shale of the Supai formation and in part of the upper surface of the Redwall limestone. The railway follows the boundary line between these two formations, in some places on the red shale and in others on the limestone. The Aubrey Cliffs are prominent in the landscape to the east as the train bears away northwestward by rising on the gentle slope of the eastward-dipping beds to the summit of the plateau of Redwall limestone. This plateau is the next "step" in the descent from the great plateau of Arizona, a descent which is begun a short distance west of Williams and continues nearly to Colorado River.

|

|

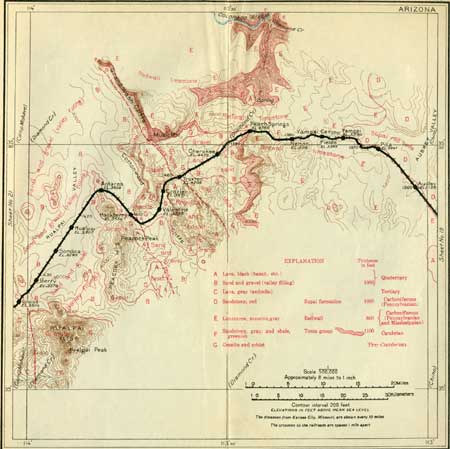

SHEET No. 20 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Pica. Elevation 5,247 feet. Kansas City 1,367 miles. Yampai. Elevation 5,580 feet. Kansas City 1,373 miles. |

At Pica (see sheet 20, p. 138) there are wells 1,100 feet deep sunk on the recommendation of a Government geologist. They furnish water for locomotives and also for a large number of cattle and sheep.

The summit of the slope of Redwall limestone is reached at Yampai, where there are cuts in this limestone. At the summit is a wide pass, west of which the train enters Yampai Canyon, cut in the Redwall limestone to Peach Springs, a distance of about 14 miles. Below Fields siding the walls of the canyon show extensive ledges of the limestone, and at Nelson this rock is quarried to a moderate extent for burning into lime.

|

Nelson. Elevation 5,106 feet. Population 300.* Kansas City 1,380 miles. |

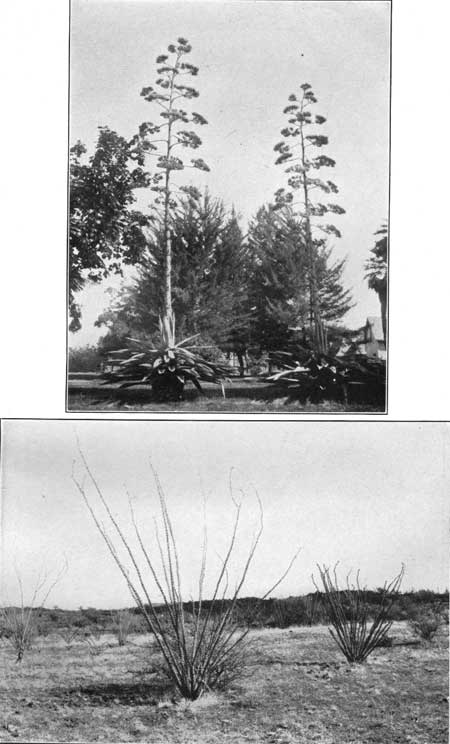

Massive beds of hard limestone, weathering to a light dove-gray color, are highly characteristic of the Redwall in this region, as also in places in the Grand Canyon where the rock is not stained red by wash from the overlying red shale. On some of these limestone walls there may be seen the peculiar mescal plant, or maguey (mah-gay', Agave americana) shown in Plate XXXV, A. After several years of growth the plant sends up a tall flower stalk which develops from a cabbage-like heart greatly prized by the Indians, who roast it in small pits in the ground. Its juice is sweet and when fermented and distilled yields the mescal brandy so extensively used in Mexico and the Southwest.

|

|

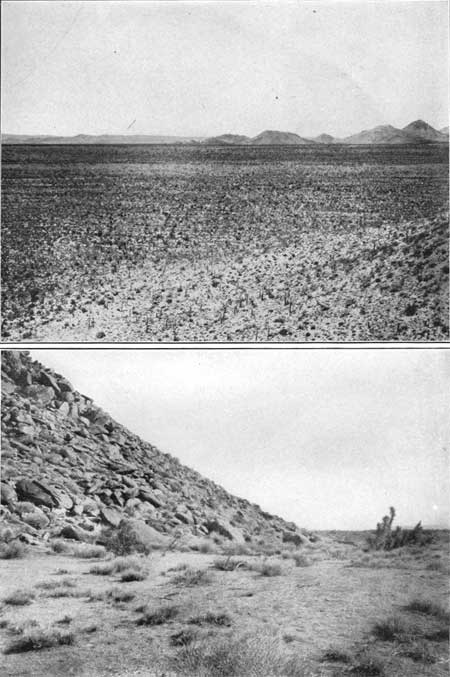

PLATE XXXV.—A (top), MESCAL, OR MAGUEY.

These plants grow at many places on the ridges in western

Arizona. B (bottom), OCOTILLO, A CHARACTERISTIC DESERT PLANT. In the spring it is covered with red flowers. |

|

Peach Springs. Elevation 4,789 feet. Kansas City 1,387 miles. |

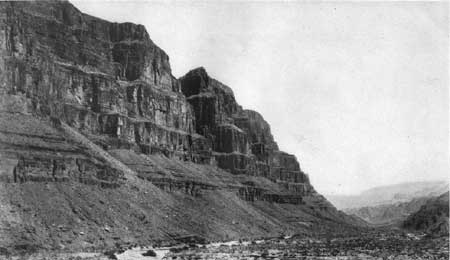

Near Peach Springs the Yampai Canyon widens into a valley known as Truxton Wash, which for some distance westward is occupied by a lava flow (basalt) that is well exposed for half a mile or more beyond Cherokee siding. The ridge north of the valley consists of Redwall limestone. On its north side there are canyons descending into the Grand Canyon of the Colorado at a point only 18 miles north of the Peach Springs station. These smaller canyons are cut mainly in sandstone and shales of the Tonto group (see Pl. XXXVI) lying on granite, which is deeply trenched in turn as Colorado River is approached. A fairly good road extends from Peach Springs to the bank of the Colorado. The walls of the Grand Canyon are not as high here as in the region farther east, yet it still has a deep inner gorge of granite extending up to cliffs and slopes of sandstones and shales of the Tonto group surmounted by high cliffs of Redwall limestone. The escarpment or cliff of Redwall limestone is prominent south of Peach Springs, where it gradually attains a high altitude, and it extends nearly due south for many miles.

|

| PLATE XXVI.—CLIFFS OF SANDSTONE OF THE TONTO GROUP IN CANYON FOUR MILES NORTH OF PEACH SPRINGS, ARIZ. Cliffs on north side of Grand Canyon of the Colorado in the distance. |

|

Truxton. Elevation 4,204 feet. Kansas City 1,399 miles. |

From Cherokee nearly to Truxton the valley widens greatly and is floored by gravel and sand washed from the adjacent mountain slopes. At Truxton the valley merges into a gorge in which appears the granite underlying the Tonto group. This granite extends northward to the foot of Music Mountain, a high cliff and peak which is prominently in view 7 miles to the northwest from the vicinity of mileposts 475 and 476. It is the same rock that is exposed in the lower part of the Grand Canyon. Music Mountain is the southwest corner of the Grand Wash Cliffs, of which more can be seen from Antares, 18 miles farther west.

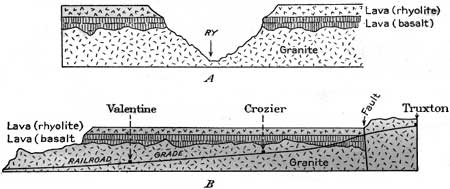

A short distance west of Truxton there appears to be a great fault crossing the railway, with the uplift on its east side. It is probably the southern extension of the fault extending along the west foot of the Grand Wash Cliffs shown in figure 33. On the west side of this fault the railway passes into a lava field and for some distance follows a narrow canyon in the lava.

|

| FIGURE 33.—Sections showing relations of granite and lava in canyon of Truxton Wash between Valentine and Truxton, Ariz. A, section across the canyon east of Valentine, looking west; B, section along the canyon, looking north. |

|

Crozier. Elevation 3,971 feet. Kansas City 1,402 miles. |

On approaching Crozier the train passes below the edge of the lava cap into a gorge in the underlying granite, which is prominent in the lower walls of the canyon nearly to Hackberry. The relations of the lava to the granite are well exposed between Valentine, as in Crozier and shown figure 33. The lava sheet constitutes an extensive elevated shelf or plateau north and south of Crozier and Valentine. It lies on an exceedingly irregular surface of the granite, filling up valleys and burying low peaks and ridges, as shown in figure 33. It was poured out in relatively recent geologic time, but before the valley of Truxton Wash was cut to the depth which it now has near Crozier and below.

|

Valentine. Elevation 3,788 feet. Kansas City 1,405 miles. |

At Valentine is a school for the Hualpai Indians on a reservation of 730,000 acres. They are a branch of the Yuman tribe and are closely allied to the Supai or Havasu Indians living in Cataract Canyon. There are about 500 of these Hualpai Indians, the remnant of a large tribe which once controlled a wide area in the middle Colorado Valley. They were famous for their prowess in hunting and their general enterprise, but are making little progress toward civilization.

The granite in the gorge from Valentine to Hackberry is characteristic of much of the granite in the ranges of western Arizona. It is very massive and coarse-grained and weathers out in typical rounded forms or huge bowlders. This process is facilitated by numerous joints,1 which cause the rock to break into large blocks; these blocks on weathering soon lose their corners, so that the resulting pinnacles and masses have rounded forms.

1Joints in rocks are cracks, generally not of great length, due to shrinkage or earth movements. They may run in various directions or may be arranged in sets of nearly parallel cracks which intersect other sets at approximately constant angles. Joints differ from faults in being much smaller fractures that show little or no slipping of the rock along the break.

|

Hackberry. Elevation 3,554 feet. Population 84.* Kansas City 1,410 miles. |

Hackberry is sustained mainly by a few small mines and ranches in the adjoining region. Here the train passes northwestward out of the granite gorge into the wide desert slope or plain known as Hualpai Valley. (See Pl. XXXVII, A, p. 140.) The Peacock Mountains, a granite ridge of considerable prominence, project out of it on the west; on its east side are granite slopes surmounted by the lava-capped plateau. The westward-facing edge of this plateau, extending far south from Hackberry, is known as the Cottonwood Cliffs.

|

|

PLATE XXXVII.—A (top), TYPICAL DESERT VALLEY

OF NORTHWESTERN ARIZONA. View northward from north end of Hualpai

Mountains near track of Santa Fe Railway. Granite Mountains to right;

Grand Wash Cliffs in the distance. B (bottom), EDGE OF DESERT PLAIN ON WEST SIDE OF HUALPAI MOUNTAINS, ARIZ. The sandy plain gives place abruptly to a slope of granite which is weathered into huge fragments. |

|

Antares. Elevation 3,608 feet. Kansas City 1,416 miles. |

At Antares the railway reaches the summit of the low northern extension of the Peacock Mountains, the granite of which crops out on both sides of the track. A few miles north and northeast are the precipitous slopes of the Grand Wash Cliffs, which extend far to the north, crossing Colorado River 75 miles north of this place, at the western outlet or termination of the Grand Canyon.

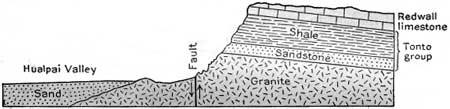

These cliffs form the last step in the descent across the great succession of sedimentary rocks constituting the high plateau of Arizona. They are capped by the lower part of the Redwall limestone, lying on 500 feet or more of sandstones and shale of the Tonto group, and have a long rugged lower slope of granite descending to the Hualpai Valley. The line of the escarpment is nearly straight. Part of its height is apparently due to a fault passing along its western foot, with uplift on the east side, as shown in figure 34. This fault probably has a displacement of 1,000 feet or more, as indicated by the extent to which the strata are elevated.

|

| FIGURE 34.—Section of the Grand Wash Cliffs, north of Hackberry, Ariz., looking north. |

At the Grand Wash Cliffs the plateau country ends, for although some of the ridges of volcanic rock to the west have tabular surfaces the great plateaus of nearly level sandstones and limestones which occupy a large portion of Arizona and New Mexico cease at these cliffs. In northwestern Arizona, southern Nevada, and California north of the Santa Fe Railway the desert basins are separated by ridges that trend northward. The Peacock Mountains, south of Antares, are the first of these ridges, and many others will be seen in the journey west to Colorado River and in southeastern California.

Doubtless the sedimentary rocks of the high plateau extended across most or all of this area in former times, but they have been broken into blocks by numerous faults and mostly removed, leaving the underlying granite bare. In places, however, the granite was covered later by great masses of volcanic material which are the most prominent features of the area.

From Antares to Kingman the railway ascends Hualpai (wahl'pie) Valley, a typical flat-bottomed desert valley, which extends north to Colorado River. It presents wide areas of smooth land with excellent soil and mild climate, which would yield large returns to agriculture if water were available for its reclamation. There is, however, but very little water underground, and although at the lower part of the valley is Colorado River, which carries a vast quantity of water, this stream lies more than 2,000 feet lower than the district visible from the railway. Pumping water to that height for irrigation is now regarded as impracticable.

At the south end of the Hualpai Valley, south of Berry siding and east of Louise siding, rise the Hualpai Mountains, a high ridge consisting mainly of granite, similar to the Peacock Mountains. On the west side of Hualpai Valley, as seen from points between Hackberry and Louise siding, there is a high ridge known as Black Mesa, consisting of a succession of sheets of rocks of volcanic origin of a character not found in the region farther east but occupying large areas in the country to the west.1

1The succession consists of an alternation of lava flows of various kinds, mostly rhyolite, with thick beds of light-colored tuff and volcanic ash, in part capped by flows of black lava (basalt). These rocks are in thick sheets, which in Black Mesa dip at a low angle to the east. They are much older than the late lava flows (basalts) of the Ash Fork country and the San Francisco Mountains, but may be of the same or nearly the same age as the older lavas of the San Francisco Mountains, Bill Williams Mountain, Picacho Peak, and Mount Floyd.

Undoubtedly these lavas were once very much more extensive than at present, for they have been uplifted, tilted, and in large part removed by erosion. They were poured out over the surface in flows, in most places to a thickness of 100 feet or more. The tuff is fine-grained material, differing from the basalt cinder in being lees coarsely cellular. It is mostly of light color and consists mainly of ash and fine-grained pumice blown out of craters and deposited in great sheets over the lava flows or other surfaces. In most places it has in turn been covered by later lava flows, the eruptions consisting of alternations of lava outflows and material ejected in fragmental condition. There were also mud flows consisting of materials similar to the tuff and ashes but poured out, mixed with water, and spread over the surface in plastic condition, in places to a thickness of 50 feet or more.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/613/sec20.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2006