|

Geological Survey Bulletin 613

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C. The Santa Fe Route |

ITINERARY

|

Kingman. Elevation 3,336 feet. Population 900.* Kansas City 1,437 miles. |

Kingman (see sheet 21, p. 148) is sustained mainly by extensive mining operations in the adjoining mountains. The mines have been opened for many years, and some of them have produced a large amount of ore. The principal mines are in the Cerbat Mountains, 8 or 10 miles north of Kingman, and are reached by a railway which branches from the main line at McConnico. Some of the ore is brought to Kingman for reduction.

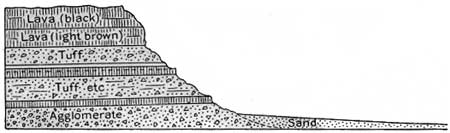

West of Kingman there are railway cuts in the volcanic series which extends south from Black Mesa. These cuts show that there are several flows of rhyolite separated by thick beds of fragmental materials. The lavas issued from vents and flowed more or less widely on all sides, the earliest one apparently filling the inequalities of an irregular surface of granite. The tuff consists of coarse volcanic ash blown out of the craters or cracks of eruption at intervals between the lava flows. Some features of the succession in the canyon between Kingman and McConnico are shown in figure 35. The beds lie nearly horizontal, and the railway descends across their edges on the down grade though the canyon. The granite floor is reached finally, and in the next few miles this rock is seen to extend along the base of the mountain to the north and south, underlying the younger volcanic series.

|

|

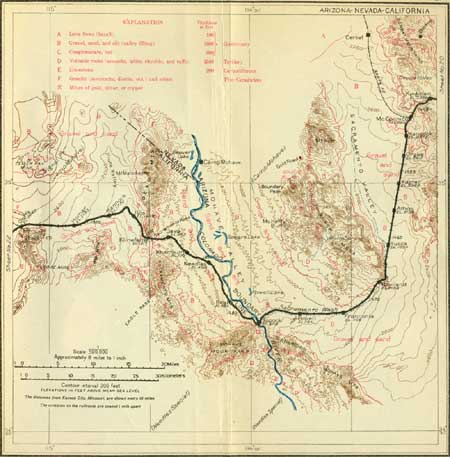

SHEET No. 21 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| FIGURE 35 Section showing relation of volcanic rocks between Louise and McConnico, Ariz., looking northwest. |

A short distance beyond McConnico is a projecting spur of the granite which shows in low cuts on both sides of the track. From Hancock, the next station, the railway goes a little west of due south across Sacramento Valley, a characteristic southwestern desert consisting of a long, wide, flat-bottomed valley bordered by mountain chains of very irregular outline and sustaining a very scant vegetation. The sandy floors of such valleys slope up gradually to the foot of the mountains, where they give place abruptly to steep rocky slopes, as shown in Plate XXX VII, B. The valleys are underlain by deposits of sand, gravel, and other wash from the mountains, and in some areas well borings show that deposits of this sort attain a thickness of more than 1,000 feet. The detrital materials partly fill valleys that were excavated at a time when the region was higher than it is at present.

At Drake siding (milepost 527) there are excellent views to the west over a typical desert valley to the foot of Black Mesa, 8 miles away. This mesa, which rises about 1,500 feet above the valley, consists of a great succession of alternating lavas and tuffs similar to those at Kingman, in beds tilted slightly to the west.

At milepost 537 there is a 10-foot cut in the valley filling, showing the succession of gravel and sands.

Erosion proceeds with considerable rapidity in the desert region, notwithstanding the scarcity of continuously running water, for rock disintegration is accelerated by the great daily variations in temperature. The rocks are heated to 125° or even higher on the hot summer days and cool off rapidly at night to 70° or less, a difference of 50° or more; and in spring or autumn, when the sun heat is less, the night temperatures are relatively lower. In winter there is frost in the higher lands, but this factor is less effective.

The weather in the deserts of the Southwest is peculiar, and so far as plant growth is concerned there are three seasons—the warm, moderately moist spring, from March to May, where growth is rapid; the long drought of June to November, when plants rest except during showers; and the winter, from December to February, when it is too cool for vegetation to advance materially.

The desert plants present considerable variety and have special characteristics that adapt them to their environment. The most conspicuous plant, covering the desert flats from Kingman, Ariz., to Hesperia, Cal., is the creosote bush (Covillea tridentata). This plant grows 2 to 6 feet high and is rather widely spaced, after the habit of desert plants, which require wide-spreading roots in order to gather the moisture from an ample area. For most of the year its leaves are covered with a resin that acts as a protection against evaporation and also renders them very unpalatable to animals. The popular name is due to the tarry odor given off when the plant is burned. On the rocky slopes and less abundantly on the plains several species of cactuses will be noted, including the barrel cactus or visnaga (Echinocactus wislizeni lecontei; Pl. XXXVIII), the smaller Echinocactus johnsoni, and clusters of the niggerhead cactus (Echinocactus polycephalus), which bears beautiful deep-red flowers in the early summer. All these cactuses are covered with large spines and contain considerable water, which is protected from evaporation by the thick skins of the trunk. The desert rats gnaw into some of them and clean out their watery pulp, leaving an empty shell of thorns. Travelers often obtain a drink of fair water from the barrel cactus. On some of the desert slopes grow the curious candlewood bushes, or ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens; Pl. XXXV, B, p. 134), the tips of which are brilliant with flame-colored blossoms in the spring. The paloverde (Parkinsonia torreyana), a bush or small tree consisting entirely of green spikes, grows in many of the valleys, associated with the una del gato (oon'ya del gah'to), or cat claw (Acacia greggii), a bush with myriads of little curved thorns and deliciously fragrant yellow blossoms. On some of the sandy soils are many yuccas or soap weeds of several species, which in the spring send up slender stalks bearing clusters of cream-white flowers.

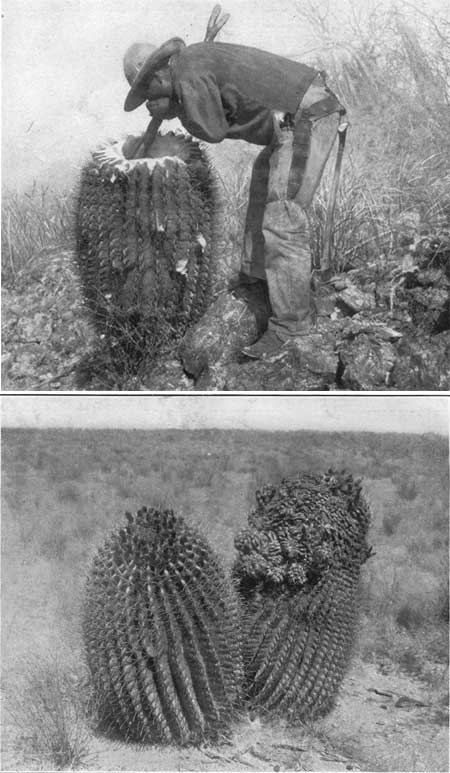

|

|

PLATE XXXVIII—A (top), A WATER BOTTLE IN THE

DESERT. Taking a drink pressed from the pulp that forms the interior

of a barrel cactus, or visnaga. B (bottom), BARREL CACTUS, OR VISNAGA. One of the larger cactuses of the deserts of western Arizona and southeastern California. |

The desert animals are small and are not often in sight. The rats, which live in large colonies in the sandy areas, are nocturnal, and most of their companions have the same habit. Various lizards and the bold little horned toad (Phrynosoma platyrhinos) are abundant, and in places the variety of rattlesnake known as "sidewinder" (Crotalus cerastes) is found. This common name refers to his side long motion both in locomotion and attack. The rare tiger rattler (Crotalus tigris) lives in the rocks in many out-of-the-way places. The Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) does not often come as far north as the Santa Fe line, but a few are reported from the Colorado bottoms near Needles and even along Virgin River in southern Utah. The larger lizard known as the chukwalla (Sauromalus ater) may be seen here and there, and the Indians find him as palatable as chicken. The tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) roams widely over the desert, and his empty shell is a common sight. Most of these tortoises are from 8 to 10 inches long; some are larger. They are generally found far from water holes, and it is a marvel that they can exist with so little water.

|

Yucca. Elevation 1,804 feet. Population 138.* Kansas City 1,461 mile. |

The railway company sank a well 1,004 feet deep at Yucca some years ago which yields a supply of excellent water rising within 104 feet of the surface.1 The east face of Black Mesa continues in view beyond Yucca. The general succession of beds in this face is shown in figure 36. The rocks present considerable variety, comprising light-colored lavas (rhyolites) and black lava (basalt) in widespread sheets of varying thickness, separated by thick deposits of light-colored tuffs, which were thrown out of volcanic vents in fragmentary condition. Extensive cuts in this volcanic series through a southern projection of the mesa show massive breccia and tuff capped by a sheet of light-colored lava (rhyolite). The breccia consists of large fragments of volcanic rocks of various kinds, and some of the material appears to have flowed out mixed with hot water. Beyond this point the railway swings to the west around the south end of Black Mesa, but it continues to follow Sacramento Wash to Colorado River at Topock.

1The water comes from a mass of tuff lying at depths of 555 to 805 feet. This tuff is underlain by 22 feet of dark lava, 78 feet of tuff, and 99 feet of "granite."

|

| FIGURE 36.—Section showing succession or volcanic rocks in east face of Black Mesa, northwest of Yucca, Ariz. |

|

Haviland. Elevation 1,465 feet. Kansas City 1,467 miles. Powell. Elevation 764 feet. Kansas City l,480 miles. |

A short distance west of Haviland siding are low terraces and hills composed of the valley filling, and at milepost 547 is a railway cut through one of these, exposing from 30 to 50 feet of bowlders and sand.

At Powell Colorado River is in sight to the northwest, occupying a broad valley between typical desert ranges. About 2 miles beyond Powell there may be seen in the foothills of the rugged mountains to the south a hole through a peak, which is known as the "Eye of the Needle." I has been eroded in a narrow ridge, largely by wind-blown sand, which is an effective agent of rock sculpture in the arid regions.

|

Topock, Ariz. Elevation 505 feet. Kansas City l,487 miles. |

At Topock (Mohave for bridge) the bank of the Colorado is reached at a point where the water is only about 480 feet above sea level. This river marks the boundary between Arizona and California, and a large bridge crosses it to the California side. To the north the river flows in a wide valley. To the south it passes into a rocky canyon through a chain of jagged ridges which extends from northwest to southeast. A group of pinnacles on one of these ranges about 3 miles southeast of Topock, and plainly visible from that place, is known as The Needles. The rocks of these mountains are largely of the younger volcanic series, similar to those constituting Black Mesa, a few miles to the northeast. They form sharp peaks of striking outline owing to rapid erosion along joint planes traversing the hard massive igneous rocks.

Colorado River was reached by two of the early Spanish explorers from Mexico in 1540; one was Melchior Díaz, who came across country and went only a short distance above Yuma, and the other was Alarcón, who came in boats from western Mexico. Owing to the custom of the natives of carrying firebrands in winter with which to warm themselves, Díaz named the stream Río del cizón (Firebrand River), a name more distinctive than the present one, which often causes considerable confusion because no part of the river is in the State that has the same name.

|

California. |

California, known as the Golden State, is next to the largest State in the Union. It is 780 miles in length and about 250 miles in average width, though owing to its shape it covers very nearly as wide a range in longitude as Texas. It has also great diversity in altitude, for some of its desert valleys are below sea level and in the Sierra Nevada are the highest peaks south of Alaska. The State has a total area of 156,092 square miles, being nearly equal in size to New England, New York, and Pennsylvania combined. The population of California in 1910 was 2,377,549, or about one-tenth that of the Eastern States named. This was a gain of 60 per cent in 10 years, The number of persons to the square mile is only slightly more than 15, having doubled since 1890, but the density varies greatly, becoming very low in the desert regions east of the Sierra Nevada. The ratio of males to females is 125 to 100. The area covered by public-land surveys is 123,910 square miles, or nearly 80 per cent of the State, and 21 per cent of the State was unappropriated and unreserved July 1, 1914.

Along the State's 1,000 miles of bold coast line there are comparatively few indentations. The bays of San Diego and San Francisco are excellent harbors, but they are exceptional.

The climate of California varies greatly from place to place. Along the coast in northern California it is moist and equable. Around San Francisco Bay a moderate rainfall is confined almost wholly to the winter, and the range in temperature is comparatively small. In parts of southern California typical desert conditions prevail. The great interior valley is characterized by moderate to scant winter rainfall and hot, dry summers. Snow rarely falls except in the high mountains.

Forests cover 22 per cent of the State's area and have been estimated to contain 200,000,000,000 feet of timber. They are notable for the large size of their trees, especially for the huge dimensions attained by two species of redwood—Sequoia washingtoniana (or gigantea), the well-known "big tree" of the Sierra Nevada, and Sequoia sempervirens, the "big tree" of the Coast Ranges. Some of these giant trees fortunately have been preserved by the Government or through private generosity against the inroads of the lumberman.

The 21 national forests in California have a total net area of 40,600 square miles, or about one-fourth of the State's area. The national parks in the State are Yosemite (1,124 square miles), Sequoia (252 square miles), and General Grant (4 square miles).

Agriculture is a large industry in California, and with the introduction of more intensive cultivation its importance is increasing rapidly. In 1914 the grain crops yielded nearly 63,000,000 bushels, of which two-thirds was barley. The value of the cultivated hay crop that year was over $43,000,000. In the variety and value of its fruit crops California has no rival in the United States, if indeed in the world. Its products range from dates, pineapples, and other semitropical fruits in the south to pears, peaches, and plums in the north, but it is to oranges and other citrus fruits and to wine grapes that California owes its horticultural supremacy. During the season from November 1, 1913, to October 31, 1914, California produced 48,548 carloads of citrus fruit, 42,473,000 gallons of wine, and 12,450 tons of walnuts and almonds. The value of the annual crop of citrus fruits is about $50,000,000, and of olives $2,200,000. Wine and brandy yield to the grape industry $25,500,000 annually. Some other notable products are hops, about 20,000,000 pounds; lima beans, 1,150,000 sacks; beet sugar, 162,000 tons; potatoes, 11,000,000 bushels; and butter, 54,000,000 pounds.

Of its mineral products, petroleum ranks first in total value and gold next. In 1914 California's output of petroleum was valued at $48,466,096, about 25 per cent of the world's yield, and its output of gold at about $21,000,000. In the production of both petroleum and gold California leads all other States in the Union. Other mineral products are cement $10,500,000, copper $5,000,000, silver $750,000, mercury $750,000, and borax $1,500,000.

California's fisheries bring a profit estimated at $3,000,000 a year, the canning of the delicious tuna yielding about $2,000,000. Nearly 11,500,000 pounds of wool was clipped in 1914, estimated to be worth $1,852,000. In most parts of the State only a small part of the water available for power or irrigation has been utilized, and large areas of swamp lands are being reclaimed. Cotton and dates promise to be important crops in the southeast corner of the State, and rice production is increasing rapidly.

Sir Francis Drake, who landed on the California coast in 1579, named the place New Albion, but later the name California was applied, taken from a Spanish romance. From 1769 to 1823 many missions were established under the direction of the Franciscan friar Junípero Serra and other missionaries of his order, and most of them still remain, although some are in ruins. The first overland caravans to California began in 1827. The discovery of gold by J. W. Marshall at Sutters Mill in 1848 brought a large crowd of gold seekers and settlers.

California was formerly a part of Mexico but in 1848 was ceded to the United States and on September 9, 1850, was admitted to the Union as a State.

At the California end of the bridge at Topock there is a conspicuous outcrop of red conglomerate in massive ledges which is part of the older valley filling. It outcrops at other places farther west, and a small mass of the same rock also appears on the east bank of the river just north of the bridge. From the bridge to Needles the railway follows the west bank of the river, and owing to the many small gullies and terraces there are numerous cuts for the railway grade. These cuts exhibit materials of the valley filling, which appear to comprise a younger, high-level gravel and sand, lying on the somewhat irregular surface of an older deposit of silt of pale-buff or greenish tint, in large part distinctly bedded. This older material lies 80 to 100 feet above the present river and was laid down at a period of slack current, during a time when there were no notable freshets for many years.

|

Needles, Cal. Elevation 483 feet. Population 3,067.* Kansas City 1,499 miles. |

Needles is built on a low terrace or higher flood plain of Colorado River, less than a mile from the river bank. It is a railway division point with a large hotel at the station, where most trains stop for meals. This hotel is named El Garcés after Francisco Garcés, a Spanish missionary who journeyed through this country in 1771-1774 and visited the Hopis in 1776. Needles is becoming a winter resort owing to its mild, equable climate and large proportion of sunny days. Many trees have been cultivated here, including date palms and the tall, stately palm Neowashingtonia filifera, a native of the Colorado Desert, which is extensively utilized for ornamental plantings in Los Angeles and other towns in the coastal region of southern California.

Many Mohave Indians live along the flats at Needles, and they have a reservation of considerable size extending along the river bank some distance above the city, where they dwell in small, low buildings roofed with brush and sand. They cultivate small areas of the fertile bottom lands along the river and raise grain and vegetables for their own use and for the local market. Some of them come to the trains, offering bead trinkets of various kinds for sale to the passengers. They are a branch of the Yuman stock, numbering about 1,400 and in general diminishing in number. The name Mohave mo-hah'vay is Yuman for the three pinnacles of the Needles south of Topock. Formerly these Indians were warlike, but this would not be inferred from their present appearance.

In the western part of Needles there is a steep ascent to a long, moderately steep slope which rises to the foot of the Sacramento Mountains1 on the west. This slope is the surface of a thick body of sand, gravel, and bowlders derived from the mountains. It is intersected by many gullies or small valleys which carry large volumes of water on the rare occasions when there is rain.

1The Sacramento Mountains consist of schists of supposed Archean age. The highest part of the mountains, 10 miles southwest of Needles, is capped by a thick body of latite. From the occurrence of fragments of blue limestone in the slope southwest of Needles it is probable that some Paleozoic rocks also occur in the range. Near the foot of the range southwest of Needles masses of red conglomerate in which are included sheets of basalt appear in small knobs and probably this material underlies the alluvium of the slopes.

Leaving Needles the train begins to climb the slope, running northwestward toward a pass that separates the Sacramento Mountains on the south from the Dead Mountains on the north. On this slope there are many railway cuts that reveal the materials of which it is composed. Some of the deposits are fine silts; others are cross-bedded sands containing a large amount of coarse material. All are of recent geologic age.

Two miles beyond Java the rocks of the mountains are exposed in railway cuts and slopes of Sacramento Wash, the valley of a stream which has cut the pass through the mountains. The material is gneiss or mica schist, probably pre-Cambrian, which constitutes the greater part of the ranges north and south.

Near Klinefelter siding this rock gives place to coarse, massive red conglomerate, which at several points rises in mounds of moderate height. This rock is not old, but appears to be a valley filling that accumulated before the deposition of the gravel and sand which form most of the slopes of the desert valley. The materials were derived largely from the adjoining mountains of gneiss, but they include also some volcanic tuff and agglomerate and old lava (basalt). The beds are tilted at various angles, the dip being to the southwest in a considerable area west of Klinefelter and almost due west, at angles approaching the vertical, along the foot of the Dead Mountains, northeast of that place. A short distance beyond Klinefelter siding a number of springs issue from this deposit, affording water which has been extensively utilized by the railway company for its locomotives. These springs are just west of the track.

A few rods east of the railway, at milepost 590, a mile north of Klinefelter, the conglomerate stands nearly vertical and includes between its beds a 6-foot sheet of basalt. At a place just east of the tracks it includes another sheet of basalt.

At Klinefelter the railway is in a wide desert valley that is drained through Sacramento Wash, which heads far to the west. To the east rise the Dead Mountains,1 culminating in Mount Manchester; to the southwest is Ibis Mountain, which ends southwest of Ibis siding. The up grade continues past Ibis to the summit, half a mile east of Goffs. The divide at this place (altitude, 2,584 feet) is in the wide sand plain of the desert, but there are ridges of granite not far to the north and south, and doubtless here this rock is at no great distance beneath the surface. At Goffs, however, in a well 926 feet deep, from which the railway company obtains water, the first rock reported was at a depth of 680 feet.

1The Dead Mountains, northeast of Ibis, consist of schists, in most of which the foliation is well defined, dipping in part at a low angle to the west. The slopes and ridges south and southwest of Klinefelter show a variety of rocks. For the first few miles there is much breccia and conglomerate that include sheets and masses of basalt. The ridges farther southeast are granite and schists. These pass down to the west under latite or rhyolite and breccia, which appears first in knobs and finally rise in prominent peaks near Eagle Pass, 10 miles south of Klinefelter. For about 2 miles the granite and rhyolite are separated by limestone and sandstone, which are of Paleozoic age and contain at one point fossils that are probably Carboniferous. Six miles southwest of Klinefelter is the high, conspicuous Tabletop Mountain, consisting of a cap of basalt on a mass of tuff and agglomerate lying west of the main body of rhyolite. The high ridge next northwest, which extends nearly to Ibis, is composed of schist and light-colored granite. The Ibis mine (now idle) is on its east slope.

|

Goffs. Elevation 2,584 feet. Kansas City 1,530 miles. |

A branch railway leading to Barnwell and Searchlight, two mining camps to the north, begins at Goffs, which is an old settlement, supported mainly by gold, silver, and copper mines in the mountains to the northeast, northwest, and south.2 The ores occur in part as veins, in part as irregular bodies of shattered altered rocks, somewhat after the manner of the ore bodies at Goldfield and Tonopah, Nev.

2A short distance south and southeast of Goffs is the north end of a mountain range which extends far southward. It consists largely of granite, partly schistose, cut by masses of darker rocks. It also contains some large bodies of diorites which are cut by the granites. Half a mile southeast of Goffs, at the foot of the main mountain mass, there is a conspicuous butte, capped by black lava (basalt). Two miles south of the station there is a high peak, known as Black Top, just west of the main mountain slope. Its tabular top is due to a thick sheet of lava (basalt), which lies on a thick deposit of sand and granite bowlders that are underlain by the coarse granite of the main mountain slope. This peak is a conspicuous feature for many miles to the west.

Three miles north of Goffs several low hills rise above the desert. They consist of white granite, a material that also constitutes the higher ridges farther north to and beyond the Leiser-Ray mine, 8 miles northeast of Goffs, and the California copper mine, 9 miles northwest of Goffs. A prominent butte known as Signal Peak, a short distance southeast of the Leiser-Ray mine, is capped by black lava (basalt) in relations to the lava caps south of Goffs and of the same age. Smaller masses of this rock also rise from the desert in low buttes 8 miles northwest of Goffs. They are parts of lava flows that were poured out over the desert surface at a time not very remote.

In the high ridges in the region north and west of Vontrigger (see sheet 22) the next station on the Barnwell branch, 10 miles northwest of Goffs, there is a thick series of Tertiary igneous rock of the same character as that in Black Mesa, near Kingman, Ariz. It overlies granite along a line that passes a short distance west of the California mine. The series consists of thick sheets of tuff and agglomerate alternating with extensive flows of light-colored lavas (rhyolite and latite). These sheets dip to the east and southeast, and the harder beds present great steplike cliffs facing the west and northwest. These cliffs are conspicuous far to the north to the traveler from Goffs to Fenner, and northwest of Fenner abut against the east flank of the Providence Mountains.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/613/sec21.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2006