|

Geological Survey Bulletin 613

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C. The Santa Fe Route |

ITINERARY

|

Elmdale. Elevation 1,195 feet. Population 253. Kansas City 154 miles. |

A boring recently made on the crest of the dome near Elmdale has found some natural gas, but the amount available has not been fully determined. Petroleum and gas occur in many places where the beds are domed, because structure of this kind offers a favorable condition for their accumulation, There are, however, numerous domes in which neither gas nor oil is found, so that this structure is not always evidence of their presence.

|

|

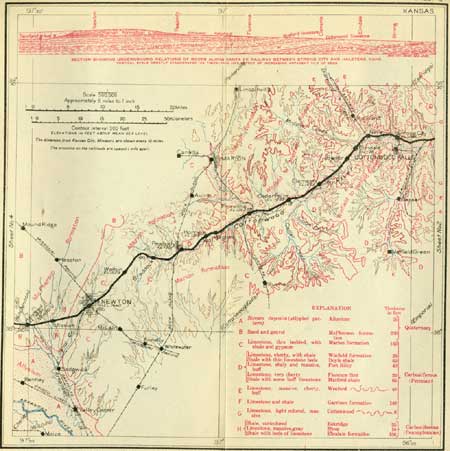

SHEET No. 3 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Clements. Elevation 1,222 feet. Kansas City 161 miles. |

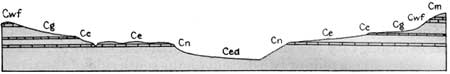

Clements is third in rank among the cattle-shipping towns of Kansas. A large number of cattle brought from various points west of this town are wintered here and fattened for market. A short distance beyond Clements is a small quarry in the Cottonwood limestone. In this part of the valley of Cottonwood River the slopes are terraced by the projection of hard layers of limestone as tabular shelves of considerable extent, each one terminating in a more or less prominent cliff, as shown in figure 4 (p. 24). In places there are three or four terraces or steps made by the succession of limestone beds, one above the other, separated by softer shales. All these beds dip to the west and are thus crossed in turn by the railway.1

1The following list shows the beds included in the Permian series in central Kansas, also their character and average thickness near the Santa Fe Railway:

Formations of Permian age in central Kansas.

Sumner group: Feet. Wellington shale: Red and gray shales 350 Marion formation: Limestone and shale with gypsum and salt in upper part 160 Chase group: Winfield formation: Cherty limestone in part and shale 25 Doyle shale: Shale with thin beds of limestone 60 Fort Riley limestone: Buff limestone 40 Florence flint: Limestone, very cherty 20 Matfield shale: Shale and limestone 65 Wreford limestone: Buff cherty limestone 45 Garrison formation: Shales and limestone 145 Cottonwood limestone: Light-colored massive limestone 6

|

| FIGURE 4.—Section across Cottonwood Valley southwest of Elmdale, Kans. Shows the terrace or steps produced by the limestone beds and the gentler slopes composed of shales. Cm, Matfield shale; Cwf, Wreford limestone; Cg, Garrison formation; Cc, Cottonwood limestone; Ce, Eskridge shale; Cn, Neva limestone; Ced, Elmdale formation. |

In this valley there is a notable difference in character between the bottom lands, which have a deep, rich soil, and the adjoining slopes, where the soil is much thinner and is in many places interrupted by the rock outcrops. The valley lands are nearly all in a high state of cultivation, yielding a great variety of farm products. At many farms the traveler will see the round towers, mostly of concrete, known as silos, in which corn leaves and stalks and other similar green materials are kept green and moist to serve as winter fodder for stock.

|

Cedar Point. Elevation 1,239 feet. Kansas City 166 miles. |

Between Clements and Cedar Point there are many shallow cuts in the shales overlying the Cottonwood limestone. At Cedar Point the Wreford limestone is crossed, but it is exposed only in a few ledges in the slopes north of the track.

A short distance east of Florence a large crusher north of the railroad is working the Florence flint and overlying Fort Riley limestone for road material.

|

Florence. Elevation 1,262 feet. Population 1,168. Kansas City 172 miles. |

Florence, named for Miss Florence Crawford, of Topeka, is a junction point at which branches to the north and south leave the main line. Beyond Florence the railway leaves the Cottonwood Valley and ascends that of Doyle Creek, a tributary from the southwest. The strata lie nearly horizontal in this region, but dip slightly to the west, forming a continuation of the general monocline which exists throughout eastern Kansas.

West of Florence the traveler will note that pasture lands become more frequent and that cattle raising is an increasingly prominent industry. At many stations there are small stockyards with special gangways for loading cattle on cars for shipment east. There are also numerous fields of alfalfa, which is one of the most important forage crops in the West.1 Some notably large fields of this plant may be seen just west of milepost 169.

1Alfalfa is generally called lucern in Europe. It is the oldest known plant to be cultivated exclusively for forage, as historians record its introduction into Greece from Persia as early as the fifth century before Christ. Its cultivation was attempted by the early colonists in America, but not until 1854, when a variety from Chile was introduced into California, did its development proceed rapidly. Alfalfa is peculiarly adapted to semiarid regions, for it does not require a moist climate and does not suffer from extreme heat or from relatively severe cold. It thrives best under irrigation, an occasional flooding being necessary for its growth. Besides being highly nutritive and palatable, alfalfa is, when well rooted, of rank growth, long lived, and hardy. It is said that in the semiarid regions there are alfalfa fields 25 years old. The best yield is obtained from the third to the seventh year. Its roots vary in length from 6 to 15 feet. Though alfalfa fields can be started in some places with a pound of seed (about 220,000 seeds) to the acre and good stands are often obtained with 5 pounds, about 15 pounds are used on irrigated lands. In seine places alfalfa is cut three to five times a season and therefore produces a higher yield than any other forage plant in the western United States. Over 5,000,000 acres were in alfalfa in 1909. Kansas has the largest acreage, with Nebraska and Colorado next in order.

|

Peabody. Elevation 1,351 feet. Population 1,416. Kansas City 184 miles. |

At Peabody, which was named for F. H. Peabody, of Boston, large numbers of range cattle are received for fattening in the adjoining region. Here the Santa Fe line is crossed by the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railway. West of Peabody the country is a wide, rolling upland, with numerous broad fields of grain, mostly wheat, interspersed with pastures. The few railway cuts show gray shales with some thin layers of limestone.

|

Newton. Elevation 1,440 feet. Population 7,862. Kansas City 201 miles. |

Newton, named for the city in Massachusetts, is a minor railway center from which a branch line of the Santa Fe leads to Wichita and other places in southern Kansas and Oklahoma. It is also on one of the larger branches of the Missouri Pacific Railway. Years ago Newton had a very large cattle-shipping business, but most of this has long ago moved much farther west.

In this vicinity and for the next 25 miles to the west there are many settlements of thrifty Mennonites, who colonized here in 1874. The railways conducted a campaign of advertising in Europe and were instrumental in settling large areas of Kansas lands with colonies of Swedish, Welsh, Scotch, English, Germans, and Russians. The Mennonites were Germans of a particular creed who on account of their thrift and industry had been invited to settle in Russia, an invitation which they accepted. Some of their special privileges having been withdrawn, however, they emigrated to this country. They brought with them many plants and for a long time held their lands in community ownership. Each family brought over a bushel or more of Crimean wheat for seed, and from this seed was grown the first crop of Kansas hard winter wheat. At first this wheat seemed to be more difficult to mill and bake than the hard spring wheat, and even Kansas millers for some time either declined to receive hard winter wheat or paid a lower price for it than for softer wheats. In 1890 the prices of soft spring and soft winter wheats exceeded that of hard winter wheat by about 10 cents a bushel. In July, 1910, for the first time the price of hard winter wheat equaled that of the softer wheats.

About 4 miles west of Newton is an area of sands and gravels which fill a broad, moderately deep underground valley in shale, excavated by a large stream that long ago flowed across the region from the north and finally deposited the gravel and sand. This stream was probably an outlet for several rivers of northwestern Kansas, the Smoky Hill and probably also Solomon and Saline rivers, now branches of Kansas River. The width of the buried valley is about 20 miles in the region west of Newton, but a short distance south of the railway it merges into the valley of the Arkansas. Its western margin is well defined by the steep slopes of the land rising toward the northwest, but to the north and northeast are valleys since excavated to a lower level. The underground relations of the deposit have been explored by well borings, for the large amount of water which it yields is of great value, especially as there is but little water available in the shales of Permian age in the adjoining lands and in the floor under the basin. This resource has been an important factor in the development of Newton. When that town needed a city supply deep drilling soon demonstrated that little water was to be found underground in the city area, even at a great depth. On the advice of geologists tests were made in the edge of the buried valley a short distance west of the city, with most satisfactory results, and now this source yields a large volume of water which is piped to the city.

|

Halstead. Elevation 1,388 feet. Kansas City 210 miles. |

From a point near Halstead a branch line runs to Sedgwick, connecting there with the line from Newton to Wichita and beyond.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/613/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2006