|

Geological Survey Bulletin 613

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part C. The Santa Fe Route |

ITINERARY

|

Garden City. Elevation 2,829 feet. Population 3,171. Kansas City 418 miles. |

Toward Garden City (see sheet 7, p. 44) the Arkansas Valley widens, the bluff on the north side receding northward and becoming a gentle slope, which continues for several miles west.

Garden City, the seat of Finney County, has wide streets, with many shade trees, orchards, and garden plots sustained by irrigation. It is the center of an extensive beet-sugar industry, and a large refinery is prominent in the northern part of the town. In 1914 about 50,000 tons of beets were worked at the refinery, yielding 13,000,000 pounds of sugar. The pulp is used for cattle feed. Several canals bring water from Arkansas River, not only for irrigation in the town but for many fields and orchards in the surrounding region. Two electric-power plants furnish power for pumping at a low rate.

|

|

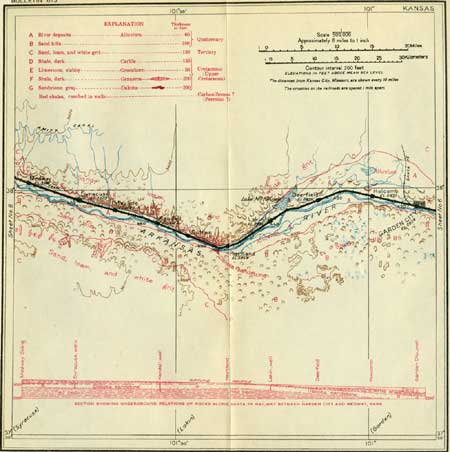

SHEET No. 7 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

At several places in the valley individuals and the beet-sugar company have been pumping water from shallow wells for irrigating crops and in general the results are satisfactory. Some of the wells yield 2,000 gallons a minute, and the supply appears adequate.

Near Garden City an irrigation project of the United States Reclamation Service, utilizing the underflow, or water contained in the sands and gravels of the low lands along the river, has been carried out. The plant is installed at Deerfield, 15 miles west of Garden City, where a number of shallow wells sunk in line across the valley are pumped to supply water for a ditch that extends along the north slope of the valley to Garden City and beyond. The cost of pumping is low because the surface of the water is not far beneath the bottom of the valley and the volume is large. Of late, however, the persons for whom the water was provided have found that it costs more than they desire to pay, so that the operation of the plant has been suspended.

The people in the Arkansas Valley in western Kansas have been asserting for many years that since the river water has been used so extensively for irrigation in Colorado the underflow in Kansas has greatly diminished. This matter was in a degree involved in the famous suit in the Supreme Court for an injunction against the State of Colorado in 1901-1907. Many experts testified for the defense that the main body of underflow was derived from the slopes adjoining the valley and that its volume was not closely related to the amount of water flowing down the river, except possibly for a few rods from the banks. Detailed observations at the wells at Deerfield and other test wells sunk by the Government proved that the line of flow in the valley deposits was mainly from the sides toward the middle.1 The thickness of the sands and gravels in this region ranges from a few feet to 400 feet, the thickness found in a boring in Garden City.

1A detailed investigation on the underflow in the Arkansas River valley in Kansas was made in 1904 by the United States Geological Survey. It was found that near Garden City the water table of this valley slopes downstream, and from the bluff lands in toward the river during ordinary stages. If, however, the river became flooded by heavy rains to the west without corresponding rains in the vicinity of Garden City the water table near the channel was raised and water spread from the river channel into the sands of the river valley, but only for a short distance. It was further ascertained that a heavy rain at Garden City would materially raise the water table in the valley with surprising quickness. The general results were as follows:

"The underflow of Arkansas River moves at an average rate of 8 feet per 24 hours in the general direction of the valley.

"The water plane slopes to the east at the rate of 7.5 feet per mile and toward the river at the rats of 2 to 3 feet per mile.

"The moving ground water extends several miles north from the river valley. No north or south limit was found.

"The rate of movement is very uniform.

"The underflow has its origin in the rainfall on the sand hills south of the river and on the bottom lands and plains north of the river.

"The sand hills constitute an essential part of the catchment area.

"The influence of the floods in the river upon the ground-water level does not extend one-half mile north or south of the channel.

"A heavy rain contributes more water to the underflow than a flood.

"On the sandy bottom lands 60 per cent of an ordinary rain reaches the water plane as a permanent contribution.

"The amount of dissolved solids in the underflow grows less with the depth and with the distance from the river channel.

"There is no appreciable run-off in the vicinity of Garden City, Kans. Practically all of the drainage is underground through the thick deposits of gravels.

"Carefully constructed wells in Arkansas Valley are capable of yielding very large amounts of water. Each square foot of percolating surface of the well strainers can be relied upon to yield more than 0.25 gallon of water per minute under 1-foot head.

"There is no indication of a decrease in the underflow at Garden City in the last five years. The city well showed the same specific capacity in 1904 that it had in 1899."

West of Garden City the traveler is fairly within the semiarid zone of the western United States, where there are large areas of public lands still available for settlement. On the plains and in the valleys the soil is rich, but in many places there is a lack of the water necessary for irrigation.

The settlers in the western counties of Kansas have had many vicissitudes, mainly caused by their constant struggle against the semiarid climate. After the terrible drought of 1860 thousands of settlers left the State. Those following the pioneers who failed in western Kansas have attacked their problems of home making with no more earnestness but with much greater success, owing to their better knowledge of the climate, of the available arid-land crops, and of methods of tillage. The dry and somewhat uncertain climate has been the greatest obstacle to permanent settlement on millions of acres of unirrigated land not only in western Kansas but in adjoining similar regions in Texas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, and South Dakota. The grain sorghums, such as Kafir, millo, and feterita, thrive under conditions of aridity and drought where corn is either a partial or a total failure. In 1893 the acreage planted to grain sorghums in Kansas was reported as well under 100,000 acres; in 1914 it was over 1,700,000 acres, and the average return per acre was several dollars higher than that for corn. In all these States the grain sorghums are now rapidly supplanting corn. Stock, however, is the principal resource of this region, for the country is generally covered with good grass which not only keeps cattle alive but fattens them for market. It is said that under ordinary conditions each head of stock requires from 5 to 10 acres of grazing land and usually more or less feeding during the severe portions of the winter.

|

Holcomb. Elevation 2,877 feet. Kansas City 424 miles. |

At Holcomb, 7 miles west of Garden City, may be noted on the north side of the track a loader of the sort in general use for dumping beets from wagons into the freight cars. The ordinary crop of beets suitably irrigated is from 10 to 15 tons to the acre and they bring about $5.50 a ton at the place of delivery, The tops are also sold for stock feed at about $3 a ton. The cost of cultivation, harvesting, and handling is $30 to $40 an acre. One ton of beets yields about 250 pounds of refined sugar.

In the vicinity of Garden City and farther west the sand hills are very conspicuous south of the Arkansas, where they cover a district from 15 to 18 miles wide. This sand has been blown out of the river bed by the prevailing northwest winds. The sand is in a thick sheet, but is blown into dunes and dunelike ridges separated by irregular winding basins. Some of the dunes are 50 to 60 feet high, and many of them have crater-like holes blown out of their tops. Much of the sand-hill area contains bunch grass and kindred plants, but other portions are bare and the sand continues to be blown farther from the river with every strong wind, while new supplies are added from the river bed. This process can readily be seen on a windy day.

|

Deerfield. Elevation 2,935 feet. Population 152. Kansas City 432 miles. |

West of Holcomb the part of the valley north of the river narrows somewhat, but the slopes are gentle and are mostly covered with crops, so that there are no exposures of the underlying formations. In this vicinity and at Deerfield the north side of the valley presents a broad second terrace or step, 50 to 100 feet higher than the river flats, a feature not common along this river. A few rods east of Deerfield station and just south of the tracks is the pumping station of the United States Reclamation Service, where water has been pumped from a series of shallow wells as already described. For a mile west of Deerfield the railway is close to the river, and the banks show thick beds of loam and sand of the later river deposits. Northwest of Deerfield is Lake McKinney, a large reservoir supplied mainly by ditches from the river above Lakin. Its water is used for irrigation in a wide district south and northeast of Deerfield.

|

Lakin. Elevation 2,991 feet. Population 337. Kansas City 440 miles. |

Near Lakin the higher lands of the plains approach the river from the north, and in the next 2 miles the steep slopes rising to them are near the track. These sandy slopes present widely scattered outcrops of a white grit rock of Tertiary age. One conspicuous outcrop of this rock is north of the track, 5-1/2 miles west of Lakin, where a knoll is capped by it. In this region there are occasional shallow railroad cuts in the alluvial materials of the valley fill.

|

Hartland. Elevation 3,049 feet. Population 373.* Kansas City 447 miles. |

Beyond Hartland the valley is narrowed greatly by the encroachments of high lands on the north and of the wide belt of sand hills on the south. The plain to the north is nearly 200 feet above the valley and is a smooth expanse characteristic of the Great Plains in general. Southwest of Hartland the Government set aside a part of the sand hills as a national forest for the cultivation of trees, but this area will be open to agricultural settlement after November, 1915. Just west of Hartland is the well-known Chouteaus Island, at a ford across the Arkansas. Here, in 1817, a French trader named Chouteau took refuge from the Indians, finally escaping. It was in this vicinity that Maj. Riley encamped in 1829 with the battalion that formed the first caravan escort sent out by the United States. On the other side of the river the battalion was met by a Mexican escort dispatched by the Mexican Government. In 1828 a party of travelers cached $10,000 in silver at this place, being too exhausted to carry it farther. A year later they went back and recovered it.

A short distance west of Hartland shales and limestone of Cretaceous age rise above the valley bottom and continue in sight on the north side of the track far westward into Colorado. The surface on which the deposits of the Great Plains were laid down was in places somewhat irregular. In this vicinity there was a hill of Cretaceous material to the west and a deep hollow in the region on the east, as has been disclosed by the excavation of the Arkansas Valley by later erosion through the Tertiary gravels into Cretaceous deposits. Two miles west of Hartland a slight arching up of the beds brings into view the Dakota sandstone, which crops out in a short line of low cliffs on the south bank of the river at the edge of the sand hills. North of the track in this vicinity, near milepost 437, a short distance east of Sutton siding, the railway is on the steep bank of the river and passes through deep cuts affording excellent exposures of the top beds of the Graneros shale, capped by the Greenhorn limestone at a plane about 20 feet above the tracks. These rocks are of Upper Cretaceous age. The shale is dark gray and mostly in thin layers. About 20 feet below its top are two hard layers consisting largely of shells of a small oyster (Ostrea congesta, a species which also occurs in large numbers in the Niobrara group). The overlying Greenhorn limestone, named from Greenhorn Creek, in Colorado, where it is extensively exposed, is soft and earthy and weathers to a light-yellow tint. It crops out at intervals to Kendall and beyond, but near Mayline and for a short distance farther west is hidden by wash on the slopes and the gravel and sand of a narrow terrace which borders the valley in that vicinity. This gravel has been dug extensively for ballast for the railway in pits a short distance north of the tracks. The Greenhorn limestone is excavated for building stone in several quarries of considerable size a mile north west of Syracuse, all visible from the railway.

|

Kendall. Elevation 3,123 feet. Population 361.* Kansas City 458 miles. Syracuse. Elevation 3,220 feet. Population 1,126. Kansas City 469 miles. |

Fort Aubrey, near Kendall, was one of the old forts garrisoned with troops to protect travelers on the Santa Fe Trail.

Syracuse is one of the larger villages of western Kansas and was long the center of extensive cattle interests before the range was broken up by homesteaders. It was settled in 1872 by a colony from Syracuse, N. Y. The Santa Fe Trail passes through the village, where a granite marker can be seen at the railway station. Syracuse has a picturesque hotel, named after the famous Cherokee half-breed Sequoyah. This Indian after being crippled in an accident turned his attention to sedentary pursuits. His great achievement was the invention of an alphabet founded upon the syllables of the Cherokee language. This was eagerly adopted by the chiefs of that tribe, and in a few months thousands of the Indians could read and write it. Sequoyah took part also in the organization of the reunited Cherokees into their new Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma.

At Syracuse the north side of the Arkansas Valley has slopes of soft impure limestone and shale, mostly covered with grass but in places exhibiting low cliffs of white Greenhorn limestone. Although soft and not very thick-bedded, it is useful for building stone, and it has been burned into lime to some extent. A part of this limestone consists of minute shells, called Foraminifera, because their shell coverings are full of pores or small holes. These tiny animals existed in large numbers in the sea from which the material in this limestone was deposited. Shells of extinct sea-living mollusks, somewhat similar to our oysters and clams, are also included in it, which indicates that this area was under the water of a sea or arm of the ocean in later Cretaceous time. This inundation covered a large portion of western America, for these limestones and shales occupy many thousands of square miles in western Kansas, eastern Colorado, New Mexico, and other States on the north and south, and it continued for a long time.1

1Under the Greenhorn limestone is about 200 feet of dark shale (the Graneros) which is penetrated by many borings in the Arkansas Valley. This shale was clay or mud deposited in the sea in the earlier stage of the submergence above referred to, but the material of the Greenhorn limestone, very largely calcium carbonate, was separated from the water by animal and chemical processes at a time when the water was relatively clear or had ceased depositing clay. This water remained clear during the long time required for the accumulation of a deposit now represented by 50 to 60 feet of limestone.

A quarry in the Greenhorn limestone is visible from the railway a short distance west of Syracuse, and low bluffs of the rock appear at intervals to and beyond Medway siding. The table-land above the slope on the north side of the valley is capped by the great sheet of Tertiary deposits already mentioned. The low white cliffs appearing at many points near the top of this slope consist of the characteristic grit of these deposits. On the south side of the valley is the broad zone of sand hills which continues to and beyond Coolidge.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/613/sec7.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2006