|

Geological Survey Bulletin 614

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part D. The Shasta Route and Coast Line |

ITINERARY

|

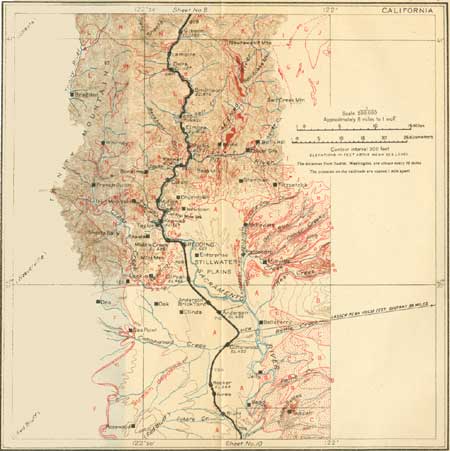

| SHEET No. 9 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

A mile below Gibson (see sheet 9, p. 70), at milepost 303, igneous rocks are succeeded by slates and sandstones (the Bragdon formation) of Carboniferous age. These continue with few interruptions for nearly 20 miles.

|

Lamoine. Elevation 1,300 feet. Seattle 656 miles. |

Good exposures of slate appear as Lamoine station is approached, and terraces, remnants of the lava flow from Shasta, may be seen on both sides of the river. About 75,000 feet of lumber, of which one-third is obtained from the adjacent Shasta National Forest, is cut daily at Lamoine. About half of this lumber is manufactured locally into boxes.

|

Delta. Elevation 1,137 feet. Population 2,786. Seattle 659 miles. |

Near Delta the Bragdon slates make rugged slopes and the forest growth becomes scanty. The light-colored digger pine (Pinus sabiniana), with its strangely thin foliage and unpinelike habit of branching, becomes prominent. Associated with it are live oaks, buckeyes, and shrubs characteristic of lower altitudes and drier climate than those of the country about Mount Shasta. From Delta stages run west over the mountain to Trinity Center and Carrville, where gold is won from both placer and lode mines.

Half a mile below Delta, on the right (southwest), is a bluff of slate overlain by 10 feet of gold-bearing gravel deposited by the river when its bed was about 70 feet higher than now. The gravel is covered by the lava from Mount Shasta, as illustrated in figure 11. Since the lava flowed down the canyon the river has cut not only through the lava and gravel but 60 feet into the slates.

|

| FIGURE 11.—Section of canyon of Sacramento River just below Delta, Cal. a, Terrace formed by remnant of lava stream that flowed down the canyon of the Sacramento from Mount Shasta to a point 10 miles south of Delta; b, ancient gravel bed of the Sacramento covered by the lava flow from Mount Shasta (gravel is auriferous); c, slates of Carboniferous age in which this canyon is cut; d, portion of the canyon (70 feet) out by the river since the lava flowed from Mount Shasta. |

|

Antler. Elevation 974 feet. Seattle 665 miles. |

The old California-Oregon wagon road crosses the river and railroad at Antler (Smithson), and the Pacific Highway crosses about 2 miles farther south. Near milepost 287 the lava flow from Mount Shasta ends. Its entire length is about 50 miles. Here the railroad crosses the river and goes through a tunnel.

|

Elmore. Elevation 804 feet. Seattle 672 miles. |

Between some of the beds of slate and sandstone, which are well exposed along this part of the route, are beds of lighter-colored gray conglomerate, generally less than 10 feet thick. Most of the pebbles are flinty, but many of them consist of fossiliferous limestone. These limestone pebbles, after long exposure to the weather, dissolve away, leaving holes that can be seen from the train. The coarsest conglomerates of the Bragdon formation, to which all these rocks belong, occur near Elmore, where the limestone pebbles contain Devonian fossils. The occurrence of these pebbles shows that the Devonian rocks (Kennett formation) were subjected to erosion and that fragments of them were rounded into pebbles by waves or streams before the overlying Carboniferous (Bragdon) formation was deposited. In geologic language the Bragdon formation rests unconformably on the slates, cherts, and limestones which make up the Kennett formation. The passage from the Bragdon formation to the Kennett formation is near a point 280.7 miles from San Francisco, but the unconformity can not be seen from the train. The Kennett formation is succeeded on the south by igneous rocks—a light-colored quartz porphyry and a greenish lava (meta-andesite—that is, altered andesite). These two rocks are closely connected with the occurrence of the large copper deposits of Shasta County. The altered andesite is older than the Kennett formation and represents volcanic action in early Paleozoic time. The porphyry is intrusive and was probably injected into the rocks with which it is associated in late Jurassic time. From this locality to Redding, a distance of about 20 miles, these are almost the only rocks visible along the railroad.

|

Pitt. Elevation 688 feet. Seattle 678 miles. |

Pitt station is near the mouth of Pit River, where that stream joins the much smaller Sacramento. A branch railroad on the left (east) leads to Heroult, where there is an extensive deposit of iron ore and an electric smelter, and to Copper City and Bully Hill, where there are large copper mines.

A mile beyond Pitt is tunnel No. 2, at the farther end of which, on the right (west), there is exposed a narrow north-south belt of Devonian slates (Kennett formation). This belt lies in a large area of meta-andesite. It probably represents material which once lay horizontally on top of the andesite but which, when the rocks were bent into sags and arches by regional pressure—folded, as geologists say—was caught in a sag (syncline) and finally squeezed together as a narrow slate belt between two masses of meta-andesite.

|

Kennett. Elevation 670 feet. Seattle 680 miles. |

Kennett is the northernmost of the three active centers of copper mining in Shasta County, and the Mammoth mine is about 3 miles northwest of the town. The ore of this region is pyritic and occurs as large bodies of irregular shape in the quartz porphyry referred to above. The fumes from the smelter are treated by the bag process before they are allowed to escape into the open air. By this means some of the zinc in the ore is saved in the form of zinc sulphate, a white pigment.

Fossil-bearing limestone belonging to the Kennett formation (Devonian) caps the ridges on both sides of Backbone Creek. Lime and ground limestone, used as a fertilizer, are both made here.

A belt of country in Shasta County, extending 25 miles northeastward from Kennett, is especially noted for its Devonian, Carboniferous, Triassic, and Jurassic fossils.1

1On McCloud River, which flows into the Pit about 6 miles east of Kennett, there are in the McCloud limestone a number of Pleistocene caverns which contain animal remains of considerable scientific interest, described by J. C. Merriam. In Potter Creek Cave, about 2 miles above the mouth of the McCloud, fossil remains of more than 50 species of animals were found in deposits on the floor. Approximately half of the total number of species were extinct. Among the animals represented in this cave were the great extinct cave bear, another bear more nearly related to the living black bear, a large extinct lion, a puma, an extinct wolf, and fragmentary specimens representing the mountain goat, deer, bison, camel, ground sloth, elephant, mastodon, an extinct horse, and a peculiar goatlike animal known as Euceratherium.

Samwel Cave, which is about 18 miles from the mouth of the McCloud, is a large cavern with many galleries, in several of which the cave earth contains remains of extinct animals. Among those is another peculiar extinct goatlike animal, known as Preptoceras.

The beautifully coiled and intricately marked fossil shells known as ammonites are especially abundant in the Triassic rocks of this region, and the Upper Triassic Hosselkus limestone of the region contains numerous remains of marine reptiles. Bones have been found representing the ichthyosaurs (fish lizards) and another peculiar marine group, the thalattosaurs (sea lizards). Numerous fragments have been obtained from these deposits, but the skeletons are nearly all imperfect and do not show the wonderful preservation of the Middle Triassic specimens from Nevada.

The history of the ichthyosaurs found in the Middle and Upper Triassic of the western region presents one of the most interesting studies of evolution thus far known in the story of this group. The Middle Triassic forms are much primitive in every respect than those of the following Jurassic period and show less advanced specialization of the limbs, tail, eyes, and teeth for life on the high seas. The Upper Triassic types also are relatively primitive but are intermediate between the Middle Triassic and the Jurassic stages of evolution.

On leaving Kennett the train crosses Backbone Creek. Here lime kilns may be seen on the right (north), and a copper smelter is farther up the creek, behind them. From Kennett southward for many miles the railroad traverses a region of desolation. The fumes from the copper smelters at Coram, Kennett, and Keswick have killed all vegetation and left bare slopes whose coloring suggests the sun-baked hills of the desert. The principal copper mines are in the hills of porphyry to the right (west). To the left, across the river, is the meta-andesite, which contains numerous gold quartz veins.

|

Coram. Elevation 630 feet. Population 666. Seattle 684 miles. |

The Balaklala copper mine is 3 miles northwest of Coram, west of the hills, and the smelter is at South Coram, a mile from the station. Across the Sacramento, opposite Motion, formerly called Copley, a bench or terrace may be discerned about 200 feet above the river. This is cut in rock and is the work of the river at a former period of its history. It may be traced from this place into the north end of the Sacramento Valley. At Buckeye, 4 miles north of Redding and about 3 miles east of the railroad, rich gold-bearing gravels, left by the river on this bench, were formerly worked.

|

Central Mine. Seattle 690 miles. Keswick. Elevation 567 feet. Population 1,437.*1 Seattle 692 miles. |

Gold-bearing quartz veins are worked at the Reed mine, on the left (east) across the river from Central Mine station. The ore is brought to the railroad by a bucket tramway.

1Including Coram and other places.

The Iron Mountain mine, which has produced copper to the value of over $33,000,000, is 5 miles northwest of Keswick, with which it is connected by a very crooked narrow-gage railway. The ore of this mine is pyritic and, although of low grade, contains considerable gold and silver. It is smelted near Martinez, on San Francisco Bay, where part of the sulphur from the pyrite is manufactured into sulphuric acid. The acid in turn is used for converting rock phosphate into fertilizer.

At Keswick the rock terrace 200 feet above Sacramento River, first noted at Motion, is visible along both banks of the river. On the west side some patches of gravel lie on the terrace.

|

Middle Creek. Elevation 526 feet. Seattle 695 miles. |

Middle Creek, which is crossed near the station of the same name, was at one time rich in placer gold, and dredges may be seen in Sacramento River below, recovering from the river gravels gold that probably came in large part from this creek. The rocky ledges along the river here are meta-andesite. In this vicinity the canyon of the Sacramento opens out into the wider valley that forms a part of the Great Valley of California. This wider portion is the area generally called the Sacramento Valley and is described below from data furnished by Kirk Bryan.2 A mile and a quarter beyond Middle Creek the river cuts through fossiliferous Upper Cretaceous (Chico) sandstone and conglomerate. These rocks unconformably overlap the older rocks of the Klamath Mountains, including the meta-andesite. On the right the bluff affords a section of the sands and gravels of the Red Bluff formation, which occupies a large area in the Sacramento Valley.

2The Sacramento Valley extends from the vicinity of Redding on the north to Carquinez Straits on the south. It is a broad, flat plain 160 miles long, 50 miles wide at the south, and tapering gradually to about 20 miles in width near Redding. The valley is 557 feet above the sea at Redding and slopes down to sea level at Suisun Bay.

The area of the valley is about 6,500 square miles, of which 2,633,000 acres, nearly two-thirds—is bottom land. On the east side of Sacramento River 535,000 acres and on the west side 424,500 acres, or 959,000 acres in all, is now subject to occasional overflow. Of this land more than 300,000 acres is protected by dikes. The total irrigable area, including the rolling land lying north of Red Bluff, is 2,500,000 acres, of which 123,500 acres was irrigated in 1912.

The principal tributaries of the Sacramento are Feather, American, and Mokelumne rivers, which rise in the Sierra Nevada. In the flatter parts of the valley overflow at some point is a yearly occurrence. The overflowed lands, which in many places support a luxuriant swamp vegetation, are among the most fertile in the valley, and levees have been built to reclaim them.

For five months, October to March, the weather is cool and rainy, but the rest of the year is practically rainless. Summer temperatures are high, reaching 115° F., but the nights are cool and the air dry The winter temperature seldom falls below freezing, and 18° above zero is the lowest temperature recorded in 60 years. Snow is almost unknown.

The character of the climate is reflected in the life of the people. With the beginning of the rains in the fall grass springs up and cattle and sheep are brought down from the mountains where they have passed the summer. The overflowed tule lands in the center of the valley are grazed in the long dry summer, but with the coming of the rains the cattle are taken to the higher plains. The grain farmer sows his wheat and barley in the fall and harvests them early in the summer. He lets his land lie fallow after the rains, to be planted dry in the fall. All the deciduous fruits bear heavily and are rarely damaged by frost. The more delicate fruits and nuts—apricots, almonds, walnuts, olives, lemons, and oranges—grow well when assisted by irrigation. There are large areas of vineyards and the long dry season is favorable to the concentration of sugar in the grape and to the drying of the grapes to make raisins.

The agricultural character of the valley is closely related to its geologic history. With the uplift of the Sierra Nevada and Coast Range in Pliocene time the valley became land, and deposition of alluvial materials began under conditions similar to those of the present time.

The alluvium is of two kinds—an older and a younger. The older alluvium is of Pleistocene or possibly of late Pliocene age and rests on the eroded edges of Miocene and older rocks. It is composed of clay, sand, and graved and varies much in appearance and composition. It is distinguished from the younger alluvium by the fact that it is now undergoing dissection by streams and by the greater oxidation and dehydration of its iron content. Because of this oxidation it is characteristically red.

The deposition of the older alluvium was followed by uplift in both the Sierra Nevada and the Coast Range. The edges of the valley were bent up and the middle gently bowed down. In consequence of this movement the older alluvium was uplifted along the borders of the valley, and streams began to cut into it. At this time began the deposition of the younger alluvium, which has continued to the present day. This material floors by far the larger part of the valley and is as varied in character as the older alluvium. The deposits are comparatively thin, probably nowhere in the valley over 300 to 400 feet thick. Every high water adds to them, and this is so well understood that farmers have been known to deliberately turn flood waters on their land for the benefit derived from the sediment left behind.

The recent alluvium is the most productive water bearer of the valley formations, largely because its gravels and sands are uncemented and porous. The water usually lies within 25 feet of the surface, but its level fluctuates with the seasons. This fluctuation is seldom more than 10 to 15 feet, a fact which indicates that a much larger volume of water is available than is at present utilized.

The Sacramento Valley is now in a state of rapid change. The overflowed lands are being divided into large districts for reclamation by levees and drainage. After reclamation they are cut up into small lots and colonized. Grain ranches are being subdivided and sold in small irrigated tracts. In consequence the population is increasing and its character is changing. The keen, intelligent irrigator, raising special crops, living a community life, and keeping abreast of the times, is replacing the old-time rancher.

|

Redding. Elevation 557 feet. Population 3,572. Seattle 698 miles. |

Redding, the seat of Shasta County, is the supply point for much of the southern part of the Klamath Mountains, especially the region drained by Trinity River and about Weaverville, a town 50 miles from Redding, reached by a daily automobile stage. The basin in which Weaverville stands has been the richest and most persistently productive gold-placer region of northern California. At the La Grange mine, reported to be the largest hydraulic mine in the world, about 1,000 cubic yards of gravel is washed each hour. A stage line runs eastward from Redding across the low Cascade Range north of Lassen Peak to Alturas, which is within the Great Basin, east of the Pacific coast mountain belt.

Redding is built on the division of the older alluvium of Sacramento Valley that has been named the Red Bluff formation. The railroad cuts in the plain south of the town show much coarse gravel belonging to this formation. To the west the gravel laps up over a terrace that is traceable around the northwest border of the Sacramento Valley and is continuous with the terrace along the river above Redding, already noted. Beyond the terrace may be seen to the northwest the rounded form of Bally Mountain (6,246 feet), composed of granodiorite, and in the west the sharper form of Bully Choop (7,073 feet), composed of peridotite.

At milepost 253 the railroad crosses Clear Creek, which drains the French Gulch mining district and on which is Horsetown, noted for its formerly active placer mines and for its Lower Cretaceous fossils. To the northeast the horizon shows the outlines of the numerous conical volcanic hills characteristic of this part of the Cascade Range. The highest of them is Lassen Peak (10,437 feet), an active volcano recently in eruption. To the left, farther north, is Crater Peak (8,724 feet), on which snow remains into July. The Lassen Peak volcanic ridge fills the 50-mile gap between the Klamath Mountains and the Sierra Nevada.

|

Anderson. Elevation 433 feet. Population 1,801.* Seattle 709 miles. Panorama Point. Seattle 713 miles. Cottonwood. Elevation 423 feet. Population 439.* Seattle 716 miles. |

From Anderson a short railroad line runs northward to Bellavista. Directly east of Anderson is Shingletown Butte, a perfect little extinct volcanic cone. From Panorama Point may be obtained the best view of Lassen Peak to be had from the railroad. Shingletown Butte is in the foreground, and Inskip Hill, a group of recent craters, lies to the right (south) of it.

A quarter of a mile south of Cottonwood station the railroad crosses Cottonwood Creek, on which, 14 miles to the west, are some peculiar sandstone dikes. Here cracks in the rocks that were formed by an ancient earthquake have been filled with sand, and the sand filling has hardened into rock, so that the dikes resemble true igneous dikes.

At milepost 236 may be had a view of the North and South Yolla Mountains, on the right (west), with snowbanks lasting into Toms Head is between them. These peaks are at the south end of the Klamath Mountains. Beyond and to the left of them is the Coast Range of California.

|

Hooker. Elevation 543 feet. Seattle 722 miles. |

A low, broad uplift of the Quaternary formations, the Red Bluff arch, runs in an easterly direction across the northern portion of the Sacramento Valley. The railroad crosses this arch through cuts in gravel near Hooker, and Sacramento River crosses it farther east, in Iron Canyon. The possibility of damming the river here affords the basis of an extensive project for irrigating 400,000 acres in Tehama County. Beyond Hooker the train passes Ivrea and Blunt.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/614/sec9.htm

Last Updated: 8-Jan-2007