|

Geological Survey Bulletin 707

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part E. The Denver & Rio Grande Western Route |

MAIN LINE OF RAILROAD FROM MALTA TO GRAND JUNCTION.

(continued)

|

|

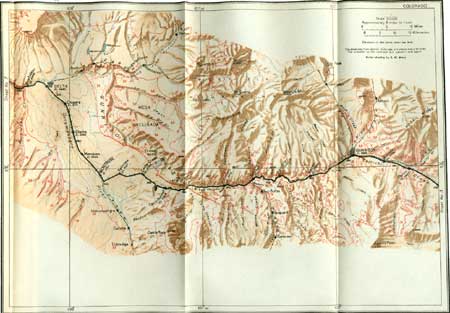

SHEET No. 6 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

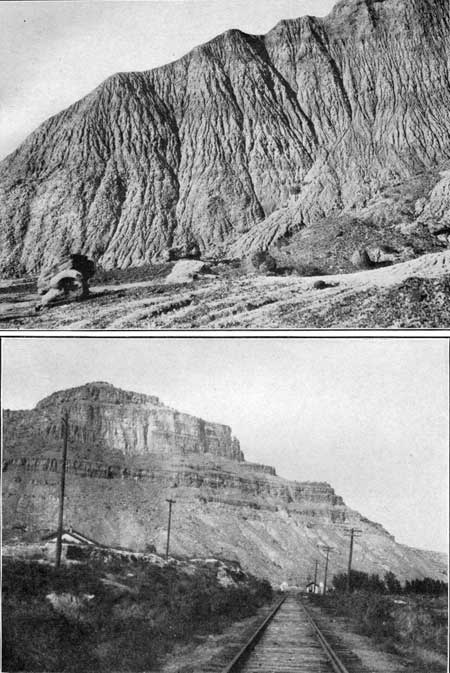

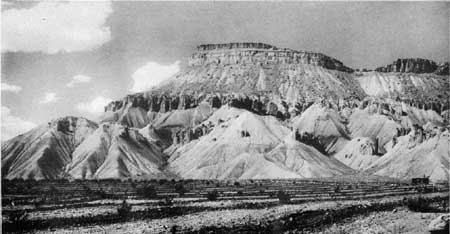

The intricate lines of sculpture that are carved by the rains in the soft shale or clay where it is not protected by a cover of vegetation or of broken rock are well shown in some badland buttes composed of maroon shale and clay of the Wasatch formation, a little more than 2 miles west of De Beque. (See Pl. LXV, A.) If the light is just right to bring out the minute lines the entire surface of the buttes will appear to be made up of a series of rill marks that resemble the delicate fretwork of an artist. (See route map, sheet 6, p. 182.)

|

|

PLATE LXV. A (top). NATURE'S LACELIKE SCULPTURE.

Fine sculpturing by the rain on a butte of red and white clay on the

right of the track 2 miles south of De Beque. Every part of the surface

is thoroughly drained, and each rivulet has carved for itself a distinct

channel. Photograph by Marius R. Campbell. B (bottom). PALISADE CANYON AT CAMEO. The walls of the canyon back of Cameo are about 1,500 feet high and are composed of sandstone and shale of the Mesaverde formation. These weather into castle-like cliffs and slopes, as shown in the view. Photograph by Marius R. Campbell. |

The rocks across which the traveler has been passing since he left Newcastle are bent into a great downfold or troughlike depression (syncline) whose east rim is composed of the coal-bearing sandstone (Mesaverde) that forms the Grand Hogback. Figure 37 (p. 148) represents the section across this trough as it is exposed by Colorado River. The other rim of the trough is crossed by the railroad between De Beque and Palisade, and through this rim the river has cut a deep and narrow canyon very different from the gap through the hogback at Newcastle. It is here called Palisade Canyon.46 As the rocks are the same at both places the explanation of the difference in the appearance of the gaps cut by the river must be sought in the difference in the attitude of the beds, or, in other words, in the amount of their dip. At Newcastle the thick bed of sandstone dips steeply toward the west, and as it is underlain by softer rocks it weathers into a sharp ridge, which can be traced for 50 miles to the north and is known as the Grand Hogback. The dip of the beds on the other rim of the trough is very slight, generally not over 10°, and the river cuts through the rim for 16 miles in a canyon that increases in depth as it approaches the outer margin of the sandstone. Figure 37 (p. 148) represents the rocks as they would appear in a deep trench cut along the line of the railroad. Above the coal-bearing rocks lies the maroon Wasatch, and in the middle and overlying all the other beds, and consequently younger than the others, are the white beds of the Green River formation, but these do not appear near Palisade Canyon.

46So far as the writer is aware this canyon has been called by no name except "Hogback Canyon," which appears several times in the Hayden reports, printed about 1875. That name was never strictly appropriate, for the ridge of slightly dipping rocks across which the canyon is cut is not a typical hogback, and as the name has never become current it seems appropriate to give the canyon the name of Palisade Canyon, from the town of Palisade.

South of De Beque the railroad is built on a low terrace at some distance from the river, but near the entrance to Palisade Canyon, 4-1/2 miles south of De Beque, halfway between mileposts 48 and 49, it reaches the river (on the left) in a shallow canyon cut into one of the thick beds of sandstone near the top of the coal-bearing Mesaverde formation. As the beds rise gradually downstream the canyon slowly increases in depth from its head to Palisade, where it ends. At Akin siding (milepost 51) the canyon walls are about 300 feet high, and they show well the alternate bands of resistant sandstone and soft, easily eroded shale. Here and there some of the beds of sandstone are thick and massive and form cliffs 40 or 50 feet high, but on the whole the alternation of shale and sandstone gives rise to sloping banded walls which have a sameness in appearance that soon becomes monotonous.

At Tunnel siding (milepost 55) the walls of the canyon have increased in height to 600 or 700 feet, but they have the same general character. A mile west of this siding the train passes through a tunnel which pierces a long spur (shaped in plan like a beaver's tail, hence the name Beavertail tunnel) that projects from the right wall of the canyon and then comes to a diversion dam which turns some of the water of Colorado River into a canal on the other side of the river. This canal is in sight throughout the length of the canyon below this point, and its effects may be noted in the crops and orchards on the high bench lands east of the river.

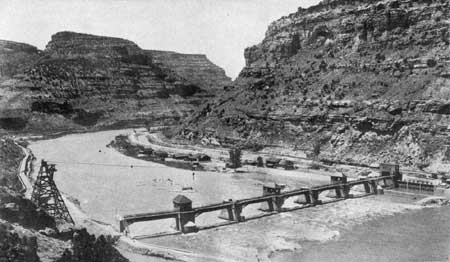

Milepost 57 marks the largest diversion project in the canyon, known as the Grand Valley or High Line project of the United States Reclamation Service, which is intended to furnish water for the irrigation of the high bench lands on the north side of the river from Palisade as far west as the western boundary of the State. The diversion dam, shown in Plate LXVI, is completed, and the canal is constructed as far west as Loma (see p. 153) and in the near future will be extended to the State line.47

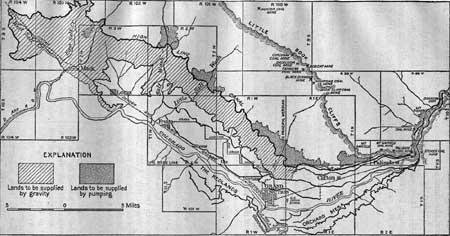

47The Grand Valley project of the United States Reclamation Service, usually spoken of as the High Line canal, provides for the irrigation of 45,000 acres of land in Mesa County, Colo., comprising, as shown in figure 39, a strip along the northern border of the valley above the old private canals from 2 to 6 miles wide and 40 miles long. The water is taken from Colorado River (formerly called Grand River) by a diversion dam (shown in Pl. LXVI) 8 miles above Palisade, into a main canal 65 miles in length, extending to a point 6 miles northwest of Mack. About 35,000 acres lies under the main canal and will be supplied by gravity, and 10,000 acres lies above the level of the main canal and will be supplied by electrically operated pumping plants.

FIGURE 39.—Map of High Line reclamation project. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) The most interesting engineering works in this project are the diversion dam and the first 6 miles of main canal, which are in the canyon of Colorado River. The dam, which is unique in American engineering, consists of a concrete weir, 546.5 feet in length, resting on a gravel foundation and provided with seven steel roller crests for regulating the height of backwater. Six of these roller crests are 70 feet long and 10 feet 3 inches in height, and the seventh is 60 feet long and 15 feet 4 inches in height. During the period of low water, when practically the entire flow of the river will be diverted, these roller crests will rest on the weir and force the water into the canal headgates, but at times of flood they will be rolled up on the piers, allowing the high water to pass over the dam in order to avoid flooding the adjacent track of the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad.

The first 6 miles of main canal parallels the railroad track, and in narrow parts of the canyon in this stretch three tunnels have been built to avoid interference with the railroad. These tunnels are, respectively, 3,723, 1,655, and 7,292 feet in length and are lined throughout with concrete. The first two tunnels are 14 by 16 feet in cross section, and the third is 11 feet by 11 feet 6 inches.

The main canal has a capacity of 1,425 cubic feet per second for the first 5 miles. About half this water will be used for developing power and will be returned to the river through the proposed power plant at the upper portal of tunnel No. 3. This plant, which has not yet been constructed, will develop about 2,000 electrical horsepower, which will be used in operating pumps to supply water to the lands that lie above the main canal.

The last 60 miles of the main canal consists of open ditch, involving about 2600,000 cubic yards of excavation, and numerous flumes, siphons, and culverts, made to cross natural drainage courses.

Laterals will be constructed to deliver water to each farm on the project, and drainage works will be built as needed to remove surplus water and prevent the rise of the ground-water level.

Water for seasoning the works was turned into the main canal in June, 1915.

The soils under the project are of three general types—reddish sand, sandy loam, and adobe. The red soil is deep and well drained and is specially adapted to fruit culture, though practically all crops do well in it; the sandy loam is an alluvial soil and is adapted to growing certain varieties of fruit as well as alfalfa, cereals, potatoes, sugar beets, and vegetables; the adobe soil is adapted to growing alfalfa, cereals, sugar beets, and vegetables.

The cost of the works is advanced by the Government under the terms of the Reclamation Act, which provides that the actual cost shall be repaid by the landowners in 20 years without interest, and that they shall pay the cost of operation and maintenance.

|

| PLATE LXVI. HIGH LINE DIVERSION DAM IN PALISADE CANYON. This great structure was thrown across Colorado River in the heart of Palisade Canyon by the United States Reclamation Service in order to divert water for the irrigation of 45,000 acres of bench land west of Grand Junction. The estimated cost of the completed project is $4,600,000. Already more than $3,700,00 has been expended, and water is now available for the irrigation of 38,000 acres. Photograph by U. S. Reclamation Service. |

The great High Line canal is crossed by the railroad a short distance below the dam and may be followed by the eye on the right until it is hidden in a tunnel that carries it through a projecting rocky point. It is carried as high as possible, and though it has descent enough to enable the water to flow readily, it is soon above the level of the railroad and can be identified only by the regularity of its banks and the new rock dumps that mark the portals of its tunnels.

Half a mile below the High Line dam Plateau Creek enters the river from the side opposite the railroad. This creek heads on the mesa far to the east and flows in a narrow valley between Battlement Mesa on the north and Grand Mesa on the south. The main automobile highway down the river is carried over the low plateau east of the river, but at Plateau Creek it descends to the river and for the remainder of the distance to the lower end of the canyon it follows the opposite bank. The walls of the canyon here are about 1,000 feet high and are therefore very imposing, especially where the beds of sandstone are particularly thick or resistant.

|

Cameo. Elevation 4,774 feet. Denver 433 miles. |

At the little coal-mining town of Cameo the canyon attains its maximum depth, about 1,500 feet. Its sides generally present the appearance of gigantic walls of masonry, the beds of sandstone forming the courses and the soft shale filling in between them like the mortar in an artificial wall. On the projecting points between the main canyon and the canyons of the tributaries the sandstone seems to form most of the wall, as it stands in gigantic pyramids that tower far above the bottom of the gorge. The pyramid on the projecting point just north of Cameo is shown in Plate LXV, B, Although the Mesaverde is the great Cretaceous coal-bearing formation in this region, it contains very few coal beds in Palisade Canyon. At Newcastle it contains more than 109 feet of coal in beds thick enough to work, but in Palisade Canyon it contains only two beds. The upper of these beds is mined at Cameo and is generally known as the Cameo coal bed. Mines may be seen just south of the station on both sides of the track. The coal from the mine on the left is brought across the river on a high trestle, which serves as a tipple for screening the coal and loading it into railroad cars. The coal mined here is of medium grade and satisfies the local demand, but it is not equal to that which is mined south of Newcastle, or in the Crested Butte region, on the east, or at Sunnyside and Castlegate in Utah, on the west. At the Cameo mine the coal bed has a thickness of 10 feet 11 inches, of which 9 feet 8 inches is clear coal.

About a mile below Cameo the High Line canal passes through the plateau by a long tunnel which brings it out on the high bench land west of Palisade.

Nearly 2 miles below Cameo the river makes a big curve to the right, and on the opposite side there is a low terrace not more than 150 feet high. This terrace has been built up by material brought down by a small creek that heads on Grand Mesa, to the east. This material is so abundant and so indestructible that it has crowded the river gradually against the opposite (west) side, so that the river has been forced to cut under a great cliff, several hundred feet in height. From the train the traveler may see that this terrace is composed almost entirely of boulders of a dark rock, which close examination would show to be basalt, or hardened lava. Grand Mesa, which here and there may be seen on the east (left) and which over-tops all other features in this region, has been preserved almost entirely because it is protected by a cap of this basalt.

Below the terrace two small water-power plants have been constructed for pumping water to higher levels to irrigate land that could not be reached by the existing gravity lines. One of these plants supplies enough water to irrigate 2,300 acres of land and the other enough to irrigate 6,000 acres. The canals and pumping plants which the traveler has seen in Palisade Canyon are more extensive than any that he has seen heretofore on this journey, and he may wonder why so much money has been spent to obtain the water of Colorado River, but when he has passed out of the mouth of the canyon and has seen the wonderful change that the water has made in the one-time desert plain he will no longer question the wisdom of the expenditure.

As the railroad makes a great bend to the west at the mouth of the canyon the traveler may notice some small coal mines that are operating on the lowest or Palisade coal bed. This coal bed, which ranges from 3 to 7 feet in thickness, overlies the sandstone that is regarded as forming the base of the Mesaverde formation. The coal bed and the sandstone are well exposed across the river, where a number of small mimes have been opened to supply the local demand for fuel. Another small mine is also in operation just above the station at Palisade. The rocks here rise more rapidly than they do farther up in the canyon, and the lower slopes of the cliffs are composed of the marine shale (Mancos) that underlies the coal-bearing formation.

|

Palisade. Elevation 4,739 feet. Population 855. Denver 437 miles. |

Near milepost 63 the canyon opens, and here begin the orchards of peaches, pears, apples, and other fruit that have made the town of Palisade famous. Its situation at the foot of the Book Cliffs protects it from late frosts in spring and from early frosts in autumn, so that almost every foot of the land is under irrigation and has been planted with fruit trees. (See Pl. LXVII.) Every year hundreds of cars of fruit are shipped from this place.

|

| PLATE LXVII. COLORADO RIVER VALLEY BELOW PALISADE. Since the waters of Colorado River have been diverted in Palisade Canyon and carried out on the level land below, the valley has been developed into a paradise of orchards and well-tilled fields. Photograph furnished by the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad. |

Here begins the great southward-facing cliff which in the early days was named Book Cliffs because of the fancied resemblance of the sandstone cap and the curved shale slope below to the edge of a bound book. A typical view of the Little Book Cliffs as they appear back of Palisade is given in Plate LXVIII. The Book Cliffs begin at Palisade and stretch westward to Castlegate, Utah, a distance of about 190 miles. They everywhere form the southern rim of the great trough of rocks on the north known as the Uinta Basin. Just west of Palisade the cliffs are formed and protected by a few beds of sandstone at the top, below which the slope consists of shale (Mancos) that was deposited there before the Rocky Mountains were in existence, when the entire region was below the waters of the sea.

|

| PLATE LXVIII. LITTLE BOOK CLIFFS AT PALISADE. The Little Book Cliffs at Palisade are capped by a hard bed of sandstone (base of Mesaverde formation), and the slopes of soft shale below are most intricately carved by rain and running water. These cliffs serve to protect from frost the acres and acres of orchards at their feet. Photograph by G. B. Richardson. |

These shale slopes have been intricately sculptured by the rain, and the traveler has many opportunities to examine them, for they are visible on the north from the train most of the way from Palisade to Castlegate. The appearance of these slopes, like that of most of the land forms in a semiarid climate, depends largely upon the light under which they are seen. When the light is strong and strikes squarely against the face of the cliffs the slopes are expressionless and dead. One slope is like another as they shimmer in the hot rays of the sun, but when the sun is low the shadows show every detail of the slopes, and thus revealed in black and white the surface of the cliffs looks as seamed and wrinkled as the face of an old man. Each slope is then full of individuality—it shows intricate and wonderful sculpture.

|

Clifton. Elevation 4,713 feet. Population 855.* Denver 443 miles. |

The valley that the railroad enters at Palisade is broad because the soft Mancos shale, in which it is carved, is about 3,000 feet thick, and its erosion has produced flat or rolling lands except where terraces have been cut by the streams into badlands or steep slopes. Although the shale contains considerable alkaline material, which is objectionable in farming, it makes in general some of the best farming land in western Colorado. Near the river it forms flat valley bottoms, as at the village of Clifton, but by proper underdraining even such flat lands may be made very productive. Orchards abound in this valley, and much fruit is shipped from Clifton. Before the water of Colorado River was diverted and carried onto this land it was a waste desert, inhabited only by jack rabbits and coyotes, but irrigation has transformed it into a fertile land, figuratively "flowing with milk and honey." Is it any wonder that millions of dollars have been spent in diverting water from Colorado River in the canyon above Palisade and in constructing great canals for delivering it to the thirsty land? But even after all our great irrigation works have been completed there will still be millions of acres of waste land, which could be converted into sites for homes of peace and plenty if water were available. The great problem of the future is to conserve all the water that is produced by the melting of snow in the high mountain regions, by holding it in storage reservoirs until it is needed, and then to distribute it to the desert land. Such work will require enormous sums of money, but it will in return supply homes to many thousands of people and bring immense wealth to the country.

General views of the valley may be obtained from places near Clifton. On the east tower the wooded slopes of Grand Mesa; on the south, far in the distance, may be caught glimpses of the gently swelling surface of the Uncompahgre Plateau—a surface composed of the massive sandstones which at some places underlie the Mancos shale and which everywhere overlie the granite that forms the basement upon which all this country is built.

|

Grand Junction. Elevation 4,583 feet. Population 8,665. Denver 450 miles. |

The railroad traverses the flat land of the river bottom to the point where Colorado River is joined by Gunnison River, which heads in the high mountains near Marshall Pass and which is followed throughout most of its course by the narrow-gage line from Salida to Montrose and by the standard-gage line from Montrose to Grand Junction. At the junction of these roads stands Grand Junction, a division point on the railroad and the largest town in western Colorado. Grand Junction is the center of a vast irrigated district whose climate is favorable to the growth of almost all kinds of grain, as well as forage crops, sugar beets, garden truck, and fruit. It is particularly noted for its beet-sugar industry and for its fruit.

The description of the country along the main line west of Grand Junction is continued on page 185.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/707/sec5b.htm

Last Updated: 16-Feb-2007