|

Geological Survey Bulletin 845

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part F. Southern Pacific Lines |

ITINERARY

|

|

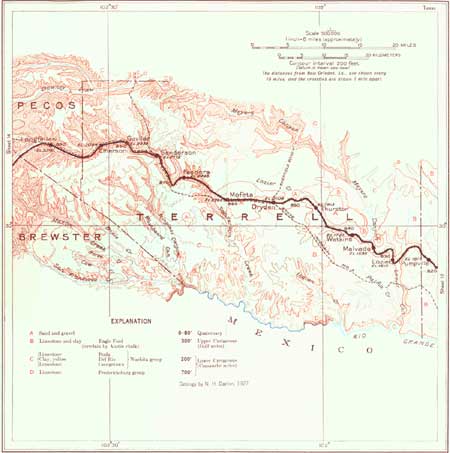

SHEET No. 13 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Pumpville. Elevation 1,817 feet. Population 30.* New Orleans 822 miles. |

Pumpville siding, a section house and pump station, is on the summit of the divide east of Lozier Creek. Wells here supply excellent water for locomotives; this water is also used for irrigation about the station with conspicuous results.

The rapid descent west from Pumpville reveals Eagle Ford buff slabby limestones and then the Buda limestone, all lying nearly horizontal. Lozier Canyon, reached just beyond Lozier siding, is a large arroyo, usually dry but in times of freshet carrying a large stream. In the canyon slopes near Lozier and past Malvado siding are many fine exposures of the Eagle Ford-Buda contact, showing conformity of attitude, with low dips to the south and east. Below the Buda, which is conspicuous as a light-colored massive limestone, are low cliffs of the massive dark-gray top member of the Georgetown limestone. The Buda limestone is in two members of slightly different aspect and texture, and the yellow Del Rio clay that underlies it to the east is entirely absent, although near the large iron bridge over Meyers Canyon 2 feet of the basal limestone of the Buda carries Exogyra arietina, a fossil characteristic of the Del Rio clay. The Georgetown limestone is exposed in the bed of the wash from Meyers Canyon to a point below Lozier. As the railroad ascends the valley of Lozier Creek past Malvado, Watkins, and Thurston sidings the chalky-white massive lower member of the Buda limestone is conspicuous in places overlain by Eagle Ford beds. On the low plateau to the north is a mantle of gravel and sand which was deposited by an earlier Lozier Creek at a higher level, a stream which had its source in the highlands far to the west. Remnants of this deposit occur south of Dryden, about Mofeta, and in the region south of Maxon Creek, 20 miles southwest of Sanderson. It contains chert, sandstone with Pennsylvanian fossils, and novaculite, from the Marathon uplift, and lavas from the Davis Mountains.

About 5 miles west of Thurston siding an increase in dip brings up the basal member of the Buda limestone and reveals the underlying Del Rio rusty buff clay, which has come in again underground and extends to and beyond Dryden.

|

Dryden. Elevation 2,108 feet. Population 60.* New Orleans 854 miles. |

At Dryden State Highway 3, which crosses the highlands to the south, comes to the railroad and continues westward for some distance along its south side. Dryden is in a broad, shallow valley bordered by low ridges of Buda limestone underlain by Del Rio clay of rusty buff color. The Buda consists of two massive limestone members separated by softer yellowish marly beds which contain distinctive fossils. A mile or so west of Dryden these strata are covered by the old river deposit above referred to, which constitutes a wide, level plain. On the west side of this plain, about 2 miles west of Mofeta siding, the Georgetown limestone comes to the surface. To the south are high mountains in Mexico, which appear to be not very distant. A short distance beyond Mofeta the railroad descends into the canyon of Sanderson Creek, which it then ascends to its head, 40 miles to the west. The picturesque canyon walls are about 200 feet high and consist of Edwards and Comanche Peak limestones at the base and Georgetown beds above, the latter mostly massive limestone but in places including some thin members of a more marly nature in which Washita fossils are found. In this area the beds rise to the west on the beginning of a large dome-shaped uplift which culminates in the Marathon Basin and Glass Mountains. Some years ago a deep boring for oil was made on the east slope of this dome at a point about 12 miles southeast of Sanderson. It penetrated all the Lower Cretaceous strata, 840 feet thick, and more than 1,000 feet of the underlying black shales of Pennsylvanian age, but obtained no petroleum. Another deep hole near Emerson, 10 miles west, had a similar result.

|

Sanderson. Elevation 2,775 feet. Population 1,254. New Orleans 875 miles. |

Sanderson is the first town of any size west of Del Rio and is a local center of trade and a shipping point for stock. It lies on the flat-bottomed canyon of Sanderson Creek, which is bordered by cliffs consisting of a massive bed of Edwards limestone lying on slabby beds of Comanche Peak limestone and overlain by a succession of massive and softer beds representing the Georgetown limestone, about 200 feet in all. West of Sanderson the canyon is ascended on a moderate grade, and as the slope of the valley and the easterly dip of the beds are about the same in rate and direction the succession of strata is uniform for several miles past Gavilan and Emerson sidings. The adjoining highlands, capped by Georgetown limestone, are so deeply incised by side draws and canyons that but little of the original plateau surface remains. The rocky slopes support a scanty growth of desert plants, and there is more or less mesquite growing in the gravelly soil of the valley floor. Just west of Emerson siding is the deep boring referred to on page 84. In places west of Emerson a diminution of dip causes some of the lower beds of the limestone succession to pass beneath the bottom of the valley, and the limestone walls become less high and precipitous.

In the region southwest of Sanderson and south of Alpine the Rio Grande makes a great deflection to the south, and the country here embraced by the river is known as the Big Bend. It is a very thinly populated region of high mountains and many deep canyons, notably those which the river has cut through some of the plateaus and ridges. One of the most notable of these is the Santa Helena Canyon, near Terlingua, which has very high, precipitous walls of limestone of the Comanche series. In the earlier days the Big Bend country harbored many outlaws, and large numbers of cattle were smuggled across the Rio Grande at fords and other crossings. It was also a favorite region for the Indians, mainly the Apache Lipans. These people utilized the abundant maguey and sotol plants, baking the buds of the flower stalk in ovens of heated rocks and fermenting the juice into an alcoholic beverage of considerable potency. Long prior to these Indians there was an earlier race which left traces of their homes and numerous pictures on cliffs.

There are many remarkable plants in the Big Bend country and other parts of western Texas. Resurrection plants, or "flor de peña" (Selaginella lepidophylla), occur in large numbers on some of the rocky surfaces; many of them are sold as curiosities. When dry they roll into a nestlike ball, but when wet they unfold into a mass of fernlike fronds of a rich green color. The Mexicans use a decoction of this plant as a cure for colic and indigestion. One of the common weeds of the region, called trompillo (trome-pee'yo; Solanum elaeagnifolium), with violet flowers and a berry like a small black marble, is much used by the Mexicans for curdling milk in making cheese. Another rather notable plant is a small, low cactus, Lophophora williamsi, of radish shape, called peyote by the Mexicans and Indians. It bears a pale-pink flower in the early summer which develops into a greenish berry in a woolly sack, formerly much chewed by Indians, especially in ceremonial prayers for the sick; some alkaloid content has a mildly intoxicating effect, so that it has been called "white whisky." Many rocky slopes are dotted with a cactus resembling a huge pincushion (Echinocereus stramineus), which bears a delicious fruit, locally called pitahaya.

The plateau region extending west from Dryden to Longfellow and beyond appears rocky and barren, but it affords fairly good pasturage and sustains many cattle; sheep and goats are also raised with a large yield of wool and mohair. The old Texas longhorn cattle have been displaced, mostly by white-faced Herefords, which make more beef, are hardier, and withstand the and climate. There are also many Brahmas, characterized by a hump and short straight horns; this stock was introduced from India and has proved to be well adapted to the dry climate. (See pl. 12, B.) The great "open range," however, is mostly a feature of the past, and now, although there are some very large pastures, all are inclosed by barbed-wire fences. The old "round-up" is no longer the great event in ranch life, and most of the branding is done at the home corral. (Turn to sheet 14.)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/845/sec13.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2007