|

Geological Survey Bulletin 845

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part F. Southern Pacific Lines |

ITINERARY

|

|

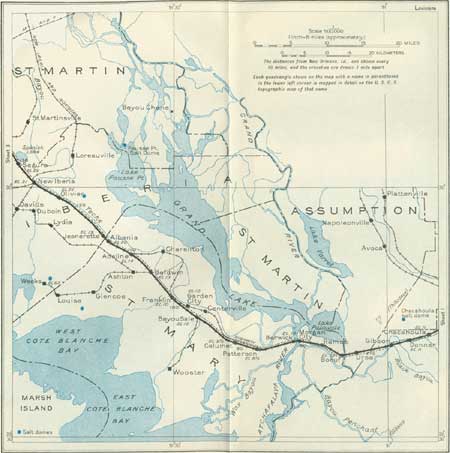

SHEET No. 2 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Donner. Elevation 11 feet. Population 900.* New Orleans 65 miles. |

Donner is in the large lowland area that was covered by the great flood of the Mississippi River in 1927, when in the lower places the water was from 6 to 10 feet deep for several months. The flooded district extended far to the north and northwest over the lake region and the country traversed by the Grand and Atchafalaya Rivers. The bayou ridges described above (p. 14) were not covered, but the water extended far up their slopes. During the flood thousands of residents on the lower lands were driven out by the water, and there was considerable loss of crops and effects. The railroad embankment near Donner was slightly submerged, and parts of it had to be protected from the flood waters. In this region the roads are surfaced with oyster shells, which make an admirable road metal for light traffic. Shells are also burned as a source of lime.

|

Gibson. Elevation 11 feet. Population 60.* New Orleans 67 miles. |

Gibson is a small village on Black Bayou, a waterway of some importance. A quaint old church is about the only feature of special interest. Gibson was formerly an extensive lumber-milling community, drawing on the rich supplies, now mostly depleted, of cypress and other trees in the great swamp country to the north. This swamp vegetation is still a picturesque feature along the railroad in places, especially the drapery of Spanish moss on many of the trees.12

12Spanish moss is extensively utilized for making mattresses and other cushions at moss "gins" at many places. The moss is cured by moistening and airing to decompose the living portion, then dried, carefully worked to remove dirt, sticks, and other undesirable materials, and thoroughly washed.

|

Boeuf. Elevation 13 feet. Population 300.* New Orleans 74 miles. |

The small old settlement of Boeuf is on the bank of an outlet of Lake Palourde, one of the water bodies of the widespread swamp region to the north. From Boeuf to Morgan City the railroad follows the north bank of Bayou Boeuf on a ridge of alluvium built up by overflows. In this general region the deposition of this material has also developed a series of islands of sufficient elevation for farming. They are not high, and in places the fields have to be protected from overflow by dikes. The soil is rich and mostly under cultivation in cane and other crops. Many scattered cypress trees remain in the swampy areas.

The extensive swamp lands in the Mississippi Valley in Louisiana are mostly useless for settlement without expensive diking, but they are valuable for growing cypress and other lumber. Some areas in the midst of the swamps that are high enough for cultivation are utilized for small farms, but even these are subject to overflow at times of high water.

|

Morgan City. Elevation 18 feet. Population 5,985. New Orleans 80-1/2 miles. |

Morgan City, on the right bank of a baylike expansion of the Atchafalaya River, is a commercial and lumber center of considerable importance, as it has waterways of moderate depth into many parts of the cypress swamps as well as into the sugarcane country. The wide river here is the outlet of a series of large shallow lakes and numerous bayous occupying the area known as the Atchafalaya Basin. It receives the water of the Red River13 mixed with some overflow water from the Mississippi River, which joins the Red River by way of the Old River near latitude 31°, 50 miles above Baton Rouge (130 miles above New Orleans). In the great flood of 1927 a large part of Morgan City was under water for two months.

13When the Mississippi River is low and the Red River is high the slope in the Old River is reversed and some of the Red River water flows through it into the Mississippi. No doubt the Red River flowed into the Mississippi River originally, but the gradual growth of a natural levee on the west bank of the big river forced the Red River to find an independent course to the Gulf down the channel now called the Atchafalaya River. This river and the Grand River have long been thoroughfares, and in earlier times many flatboats were used for freight transportation, going mostly by way of Plaquemine Bayou and locks to the Mississippi.

Morgan City (originally Brashear, later renamed for Charles Morgan14) is near the head of tidewater and from 1850 to 1869 was the terminus of the railroad from New Orleans. At that time there were extensive boat connections in all directions by the rivers and bayous, and by way of the Gulf of Mexico to Galveston. The United States Government took possession of these communications during the Civil War. Charles Morgan, who had controlled most of the boat lines, purchased the railroad in 1869; it was extended west to Lafayette in 1880. Formerly the city's lumber business was extensive, but now the principal occupations are agriculture, shipping crabs, and preparing shells for chicken feed and other uses. The shells are brought from the large reef of Pointe au Fer in Atchafalaya Bay, 30 miles southwest of Morgan City. One of the water routes of commerce in the region now is by the Grand River and a 7-foot canal through Plaquemine Lock, which enters the Mississippi River 20 miles below Baton Rouge.

14Charles Morgan is regarded as one of the most important influences in the development of southern Louisiana. He was born in Connecticut in 1795 and died in New York City in 1878. He inaugurated various early coastwise steamship lines, mainly to places on the Gulf of Mexico, developed the railroad from New Orleans to Cuero, Tex., and dredged a steamboat channel through Atchafalaya Bay. In 1836 he founded a great iron works in New York, and in the same year he sent the first vessel from New Orleans to Texas, stopping at Galveston when that place consisted of one house.

The projected Intracoastal Waterway is to follow Bayou Boeuf into the Atchafalaya River at Morgan City and thence go westward through Wax Bayou.15

15This waterway is being built by the Government to provide an inside channel along the coast from New Orleans to Corpus Christi (at a cost of $16,000,000) and, eventually, to the Rio Grande at Point Isabel. The bill passed by Congress in 1927 provides for a canal 100 feet wide to carry 9 feet of water. Many natural water bodies are to be utilized, some of them, however, requiring deepening and straightening. For much of its course it is from 10 to 20 miles south of the Southern Pacific lines.

|

Berwick. Elevation 14 feet. Population 1,679. New Orleans 82 miles. |

After crossing the Atchafalaya River over a long bridge the train reaches Berwick, a companion town to Morgan City and sharing with it the river trade and crab industry. In the region west of Berwick much of the land is under cultivation in sugarcane, but some woodland remains. An abandoned sugar mill (Glenwild) is conspicuous north of the railroad 3 miles west of Berwick.

A typical small sugar plantation may be seen just north of the tracks 2 miles beyond Patterson (near Calumet siding), with groups of whitewashed houses for laborers and many very large, handsome moss-hung live oaks.

|

Patterson. Elevation 8 feet. Population 2,206. New Orleans 88 miles. |

The principal outlet of Grand and Sixmile Lakes, at a point about 4 miles north of Patterson, is regarded as the beginning of the lower Atchafalaya River, and into it empties the famous Bayou Teche (Indian for Snake Bayou) at a point about 2 miles north of the town. This bayou originates far to the northwest. Running along the west side of the great alluvial valley of the Mississippi, it has built up a typical bayou ridge, 10 to 20 feet high, that is extensively settled and cultivated. The railroad is built upon this ridge from Patterson through Franklin, Baldwin, Jeanerette, and New Iberia, and in places the water of the bayou is visible from the train. With its many plantations, fine houses, luxuriant gardens, and handsome live oaks and pecan trees, it is one of the most interesting features in southern Louisiana. The bayou is a useful waterway, although at present the traffic is light.

In early days the bayous and rivers were highways of travel to the Acadians and other settlers, who built their houses overlooking them. The settlers used pirogues, or dugout canoes, and flatboats for transporting themselves and their produce from place to place, traveling by day only and camping on shore at night. Later on, in the French and Spanish régimes, every grantee of land was required to build a levee along the bayous and on top of it a road. Such was the origin of the Spanish trail from New Orleans to San Antonio that goes through Lafayette and of many other roads still existing in southern Louisiana.

There is a much used airport in the midst of the cane fields about 3 miles west of Patterson. Cane fields extend far westward up the "Teche country," with sugar mills at several places, including Shadyside and Bayou Sale. At Garden City a sawmill is in operation, using logs floated up Bayou Teche from the Grand Lake region.

|

Franklin. Elevation 10 feet. Population 3,271. New Orleans 102 miles. |

Franklin, on the south bank of Bayou Teche, is an old commercial and sugar center, with large lumber and planing mills. Recently the operation of these mills has had to be discontinued, as the supply of cypress became exhausted or too remote.

Louisiana is not usually regarded as an earthquake region, but it has experienced occasional quakes. The last notable event of the kind was the earthquake of October 19, 1930, the epicenter of which was in the Atchafalaya Valley between Franklin and Donaldsonville.

|

Baldwin. Elevation 13 feet. Population 822. New Orleans 106 miles. |

Baldwin is a local center of the sugar business and of a district in which various crops are raised on the Bayou Teche ridge and the slopes extending south. A branch railroad and a highway lead southwestward to the Cypremort sugar refinery and the great salt mine at Weeks Island (or Grande Côte). (See p. 21.)

In traveling across central-southern Louisiana the only visible features of geologic interest are the delta and bayou deposits, especially the mounds built by bayou and river overflow which have been referred to on previous pages. Farther west are the wide terrace plains of low altitude, floored by alluvial deposits of Recent age. It would scarcely be suspected that under this smooth cover there are formations which represent a long and complex geologic history. Many deep borings have revealed this subsurface geology to a depth of 8,000 feet or more. Below the Eocene beds is a great thickness of earlier Tertiary, Cretaceous, and older strata down to the crystalline rocks which underlie them. The principal formations so far recognized are listed in the following table:

Formations of Quaternary and Tertiary age underlying southern Louisiana

| Age | Formation | Character | Thickness (feet) |

| Pleistocene. | Beaumont clay. | Clay and sand. | 1,500+ |

| Lissie gravel. | Sand and gravel. | ||

| Unconformity | |||

| Pliocene. | Citronelle formation. | Nonmarine; yellow and red sand and clay. | 50-400+ |

| Unconformity | |||

| Miocene. | Pascagoula clay. | Marine in part; blue-green and gray clay, some sand. | 250-1,400(?) |

| Unconformity | |||

| Hattiesburg clay. | Nonmarine; blue and gray clay, thin sand, and sandstone. | 300-350 | |

| Catahoula sandstone. | Nonmarine; gray sand, sandstone, fine conglomerate, clay. | 600-800 | |

| Eocene. | Jackson formation. | Marine; gray sand and dark calcareous clay. | 100-600 |

| Cockfield formation. | Palustrine; gypsiferous sand and clay with lignite. | 400-800 | |

Some recent estimates suggest that in the southern part of the area the Pliocene and later beds are 4,000 feet thick, the Miocene 4,000 feet, the underlying Tertiary more than 10,000 feet, and the Cretaceous possibly as much as 8,000 feet. This great succession of sediments indicates that the region was under water for a long time, during which a vast amount of material derived from the land was deposited. During this deposition the basin kept sinking much of the time, and doubtless the total amount of subsidence was fully 5 miles. There were also intervals of uplift when the land was above the water, a fact indicated by unconformities between most of the formations above listed. There is evidence that the region is still subsiding, for a few centuries ago cypress swamps were much more extensive, than at present, as shown by the dead cypress on Cypremort Point and by the stumps of cypress in Weeks Bay, exposed at very low tide.

Southern Louisiana has had a somewhat complex fluviatile history, some of it decipherable from the resulting configuration or the distribution of deposits. Near New Iberia there are small areas of characteristic Red River deposits, which indicate that at no distant date the Red River drained south for a short time through Bayou Teche. Deposits of the latter stream overlying the low terrace plain southeast of New Iberia indicate that for a while this bayou overflowed its banks in the wide gap east of New Iberia and reached the Gulf between Avery Island and Weeks Island. (Howe.)

|

Jeanerette. Elevation 19 feet. Population 2,228. New Orleans 115 miles. |

Jeanerette is an old and picturesque village named for an French settler, Jean Erette, who operated a small corn mill. For many years the principal industry of Jeanerette was sawing cypress and other lumber brought from the swamps far to the northeast, but this activity has ceased because the sources of supply have become too remote. There is, however, considerable farming and dairying, and rice and cotton are produced. Formerly there were many small sugar mills in the vicinity, but only a few remain; one about 2 miles west of the town, on the bank of Bayou Teche, is conspicuous from the railroad.

From Jeanerette northwestward the railroad follows the high south bank of Bayou Teche through cane fields and small woodlands. Throughout this district fine live oaks festooned with Spanish moss are conspicuous, many of them surrounding stately old homes. Among these are the Delgado-Albania plantation, on the bank of Bayou Teche, now owned by the city of New Orleans, and several other notable old estates, such as Bayside, Westover, Loisel, and Beau Pré, all surrounded by fine trees. About 5 miles west of Jeanerette, on the north bank of the bayou, is the livestock experiment station, 1,000 acres in extent, sustained by the cooperation of the United States Department of Agriculture and the State of Louisiana.

|

New Iberia. Elevation 20 feet. Population 8,003. New Orleans 127 miles. |

New Iberia, one of the oldest settlements in southwestern Louisiana, is a commercial and sugar center at the junction of several local railroads. Situated on the bank of the Bayou Teche, it has water communication with many places. It was incorporated as a town in 1839, and it is said that fully 80 per cent of the people are descendants of the Acadians.

These people originally were French Settlers in Grand Pré, Nova Scotia (French Acadie), where they had lived for a century and a half before the English conquest in 1755. Then, when they refused to transfer their allegiance to England, their property, so industriously accumulated, was confiscated and they were deported. During the following decade many of them sought refuge in the French colony of southern Louisiana, where, however, they found conditions not entirely congenial, for Spain had just acquired control of that territory. But they were cordially welcomed, and many established themselves in the moist, fertile lands along the bayous, an environment far more agreeable than the rugged north country to which they had been accustomed. The effect of this propitious climate upon their character was diverse: some were content with a bare subsistence; others developed into landowners and men of affairs whose hospitality and graciousness were famous. Many descendants of the old Acadians remain, together with a large percentage of persons of French descent from the original New Orleans colonies. The local name for these people represents the defective pronunciation "Cajun." One group of Acadians that left the Mississippi at Plaquemine and came southwest though the swamps in 1757 found a small settlement at the present St. Martinsville, 9 miles north of New Iberia, where the newcomers were given tracts of land. Trappers, traders, and ranchers were scattered sparsely though the Teche country, and under the Spanish régime the settlement became a headquarters and finally a military post called the Poste des Attakapas (a-tak'a-pa). Four different flags have floated above it. Now, under the name St. Martinsville, it still has an Acadian population, dialect, and atmosphere, and these, together with its ancient structures, render it a most interesting place to visit. The region is perhaps most popularly known from Longfellow's narrative poem of the fair Acadian "Evangeline," the scene of which is laid principally on the Bayou Teche. At St. Martinsville is the heroine's grave, under the "Evangeline oak" in the yard of the church constructed in 1765, and various souvenirs of her life are on exhibition. In this headquarters of the old Acadian colony a monument in memory of Evangeline was erected in 1931, for she had become to the "Cajuns" the symbol of their early sufferings, their romance, and their faith.16

16It is locally stated that Longfellow based his poem on the narrative of an old Acadian in St. Martinsville but modified it to have a different ending. The young woman referred to was Emmeline Labiche, and "Gabriel" was Louis Arceneaux, who told Emmeline that after waiting a long time for her to come he had given his promise to another. Demented by the blow, she wandered through the Teche region and finally died and was buried in the churchyard at St. Martinsville. In places here the beds dip 44°. The lignite, which is 18 feet thick, may have economic value.

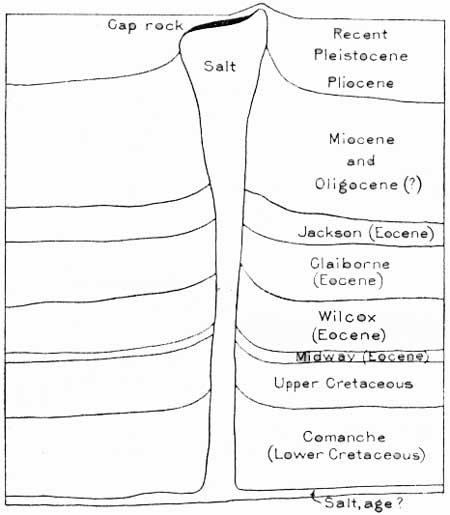

Eight miles south of New Iberia the hill known as Petite Anse, or Avery Island, rises prominently above the lowlands and marsh. Its height is 152 feet, and it is dimly visible from the railroad. It consists of a thumb-shaped mass of salt thrust up several thousand feet though the Coastal Plain deposits. The salt has been extensively mined for many years from a shaft about 200 feet deep, and great galleries, such as are shown in Plate 4, B, extend far underground in white salt. Borings 2,263 feet deep have not reached the base of the deposit. A feature of this kind is known as a salt dome, and its general relations are shown in Figure 1. Similar bodies of salt occur at the mounds constituting Jefferson Island, 8 miles west of New Iberia, and Weeks Island, 15 miles south of New Iberia, where it is also extensively mined for domestic use and for the manufacture of sodium chemicals. The production of salt at these localities has exceeded 7,000,000 tons, valued at more than $27,000,000,17 and the supply is practically inexhaustible.

17Mineral Resources of the United States.

|

| FIGURE 1.—Hypothetical section of salt dome at Avery Island, La. By H. V. Howe |

The three "islands" above mentioned and two smaller ones to the southeast occur along a line bearing N. 49° W., which probably marks a narrow deep-seated zone of uplift or faulting that extends across the country for many miles. The movements along this line, especially at the domes, have continued into recent times. Owing to the uplift of the strata the domes reveal formations which in the adjoining region are concealed by alluvial deposits. At the surface there is more or less loam resembling loess, 10 feet or more thick, and in many places where this has been removed by erosion older gravel (Citronelle, p. 19) is exposed. On Avery Island there are small exposures of sandstone, clay, and lignite which may be of Pliocene or Miocene age.

At Jefferson Island there is a small mound only 75 feet high, but it has been found by recent boring that the area of doming is considerably larger, the salt core extending under Lake Peigneur; the depression in which the lake lies may be due to subsidence caused by the removal of salt by underground solution.

There have been several theories as to the origin of the numerous salt domes in the Coastal Plain of Louisiana and Texas, but most geologists regard them as due to the flow of the relatively plastic salt from a deep-seated stratum, to relieve stress in the earth's crust. The salt body has forced its way through the overlying sand and clay and to some extent domed and faulted the strata. The top of the salt core has risen to various heights in the different domes, but in one dome it is 6,400 feet below the surface. The domes near New Iberia above mentioned give rise to surface mounds of greater or less height, and the salt is near the surface, but in many salt domes the salt body lies deep and there is no topographic indication of its presence. Not long ago the only domes recognized were those which had surface manifestations, but exploration with the torsion balance and seismograph, instruments which detect the disturbances to gravity and to rock conductivity resulting from the uplift, has indicated the presence of many more, and drilling has verified their existence.18 In some of the domes the disturbed strata surrounding and overlying the salt core serve as a reservoir for oil. The association of petroleum with many of the domes is believed to be due to a condition favorable for its migration and accumulation. About 80 domes are now known in the Louisiana-Texas Coastal Plain. More than two-thirds of them produce petroleum, with an aggregate of nearly 70,000,000 barrels in 1930, according to the United States Bureau of Mines. The sulphur and anhydrite occurring as cap rocks on most of the domes have resulted from secondary chemical reactions. The structure of a typical dome is shown in Figure 2, but there is considerable variety in character, form, and relations and in the depth to the top of the salt mass.

18A deeply buried salt mass has been discovered on the western margin of Lake Fausse Pointe, about 11 miles east-northeast of New Iberia. The only surface manifestations of the uplift were some gas emanations and paraffin in the soil, but a seismograph survey in 1926 showed the presence of a dome, and a boring found salt at 1,392 feet. Several borings found petroleum, the first one yielding 125 barrels a day from sands probably of lower Pliocene age lying at a depth of 1,062 to 1,143 feet, 100 to 200 feet above the salt core. The field attained a production of 16,800 barrels in 1927. The salt core is more than 2 miles in diameter and at one point comes within 823 feet of the surface. Another salt dome that underlies a small area about 6 miles east of New Iberia afforded a small production of petroleum in 1916-1920. Several borings in this dome that reached a depth of more than 3,000 feet are thought to have entered beds of Miocene age. The apex of this salt core comes within 805 feet of the surface. (Howe.)

The easternmost is the Chacahoula dome, 3 miles north of Donner, discovered by seismograph exploration. Here the salt was penetrated in a test boring at a depth of 3,485 to 5,150 feet, where boring was stopped. No boring in these domes has passed entirely through the salt, although some holes have been drilled 4,000 feet in it.

The sandy loam exposed on Avery Island has yielded fossil shells of no very great geologic antiquity, and bones of the mammoth, elephant, buffalo, horse (Equus complicatus), Mylodon, and Megalonyx, all of which have been extinct for a long time (Howe). These deposits have been correlated with the Sangamon or third interglacial stage, indicating that Avery Island has stood above sea level since that time. Remains of man have been found associated with the bones, but paleontologists have not been fully convinced that they were contemporaneous.

The fact that the salt marshes stand above sea level indicates that Avery and the other islands can not be very old, for in such a moist climate reduction of the salt by solution would progress rapidly, although possibly the salt is rising at a rate to keep pace with solution. Although Avery Island and the other mounds rise but slightly above the general low plain and marsh, they have some notable characteristics of flora, due mainly to soil differences, and also some peculiarities of animal and insect life.

A sanctuary for herons and other birds, established on Avery Island in 1894, is locally estimated to give refuge to over 1000,000 herons, the same birds returning year after year. Some of the birds are labeled, and a record is kept of their zones of migration. Many wild fowl winter in Louisiana, but the draining of wet lands has diminished their former plentiful food supply, so that now large numbers of birds move on to Central America and Mexico. Myriads of blue geese come from their breeding grounds in Baffin Land to spend the winters in this region. As the number of birds has decreased, the sale of wild birds has been made illegal, and the hunting season and the bag limit are much reduced. On Avery Island also is a large arboretum in which a great variety of semitropical plants have been assembled.

On this island is manufactured the famous tabasco sauce, a fiery but savory essence of a special pepper imported from Mexico, which thrives in the warm climate of this region; many of these peppers are also dried and ground for flavoring. The cultivation of this pepper and the bottling and shipping of the sauce give occupation to many persons living near New Iberia. Another special industry here is a paper mill in the east edge of the town that utilizes rice straw, a material which is largely wasted under ordinary conditions of harvesting. Considerable sugarcane is raised near New Iberia, and corn and vegetables are grown.

One of the most noticeable topographic features in the vicinity of New Iberia is the northward-facing margin of the Hammond terrace, 10 to 15 feet high, which extends northwestward from that place. It is ascended by the railroad a short distance west of New Iberia. Beyond Segura it forms the south bank of Spanish Lake, on some maps called Tasse Lake, which lies between it and the natural levee that Bayou Teche has built up. To the west it merges into the general upland which lies west of the lowlands of the Mississippi Valley. Just east of Lafayette the terrace step is only about 12 feet high, but at Opelousas, 25 miles northwest, its steep eastern face is a bluff nearly 40 feet high. Its elevation is 35 feet near Rayne and for some distance beyond. The land is better drained than the lowlands of the valley of the Mississippi or the low prairies to the south, and it contrasts also in having a slightly rolling configuration and sandy soil. Refugees of the flood of 1927 went to this upland near Segura as the nearest highland that was available. At the crest of this flood the swamp lands to the north were under 5 to 10 feet of water, and even New Iberia was inundated for several days. This flood was the first in a century that overflowed any of the country south of Bayou Teche.

Southeast of New Iberia there is a terrace or upland somewhat similar to the Hammond terrace, lying south of the Bayou Teche mound and extending to and beyond Jeanerette. South of this terrace is a lowland flat that extends as far to the west as Vermilion and Mermentau Prairies, which are mostly less than 20 feet above sea level. (Turn to sheet 3.)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/845/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2007