|

Geological Survey Bulletin 845

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part F. Southern Pacific Lines |

ITINERARY

|

|

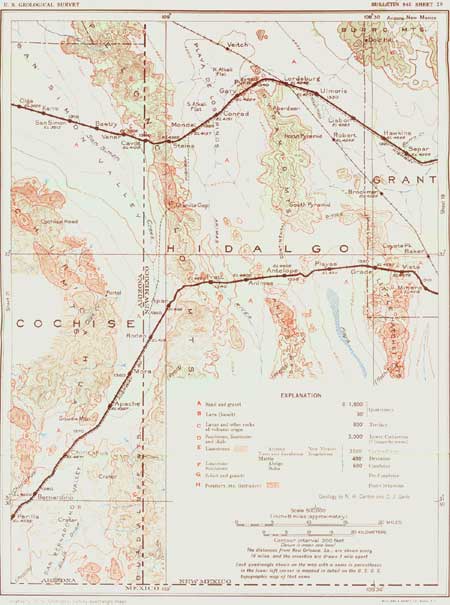

SHEET No. 20 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Far to the south is Big Hatchet Mountain, and to the southwest the Pyramid Mountains are prominent. The yucca (see pl. 20, A), which has been abundant for many miles along the tracks, continues to be the most noticeable element in the sparse vegetation. It blooms in June and early July.

|

Lordsburg. Elevation 4,248 feet. Population 2,069. New Orleans 1,336 miles. |

Lordsburg is a busy town with local stock and mining interests, and a Government airport, which is extensively utilized throughout the year. A branch line leads to the mining community of Clifton, Ariz., and another branch goes southeast to Hachita, on the south line of the railroad. Lordsburg lies just north of the north end of the irregular group of ridges, buttes, and peaks of the Pyramid Mountains, in which there are several active mines. One of these, known as "the 85," is in sight as the train approaches Lordsburg. It lies in a cove at the foot of the mountains and ever since its start, in 1885, has been productive of gold, silver, and copper. The mineral veins cut volcanic rocks, and some of them crop out as dark "reefs," which are conspicuous in the hill slopes. There are other mines farther south, and Gold Hill, 14 miles northeast of Lordsburg, has long been a producer of gold from quartz veins in the old crystalline rocks. The Pyramid Mountains consist of an extensive succession of igneous flows and intrusions, apparently of Tertiary age. The greater part of the range is andesite of porphyritic texture, but there are masses of diorite porphyry in the western part of the mining district, near Lordsburg. Considerable brecciation has occurred in parts of the area, and there are many mineralized veins, some of which have yielded a large amount of ore containing silver, lead, copper, and gold. The Lordsburg district furnishes 60 per cent of the New Mexico production of gold, also considerable copper, mostly from the deeper workings. The total metal production from the district is estimated at $18,000,000. All the ore is shipped to smelters at El Paso, Tex., and Douglas, Ariz. The deepest shaft is 1,700 feet deep.

Passing around the end of the foothills10 of the Pyramid Mountains west of Lordsburg and between a group of outlying hills of lava, the railroad deflects southwestward to reach Steins Pass. It crosses the bare wide level-floored basin of the Playa de los Pinos, which contains two large "alkali" flats north of the railroad. Sometimes these flats are covered by water, but usually they present a glistening surface of crystalline salts, often giving rise to striking mirages. This basin is a northern extension of the Animas Valley (see p. 168), so deeply filled with detritus that the rise to the divide at Steins is only about 200 feet.

10One of these hills a mile west of Lordsburg, south of the railroad, consists of quartzite faulted against igneous rocks and probably of Lower Cretaceous age. The hills just northwest of Pyra siding are due to a sheet of lava capping volcanic tuff (Tertiary). This rock is a latite carrying phenocrysts of plagioclase and hornblende in a fine-grained groundmass rich in orthoclase.

|

Steins. Elevation 4,352 feet. Population 40.* New Orleans 1,355 miles. |

The highway to Douglas and the Southwest leaves the railroad a short distance east of Steins (locally pronounced steens) and reaches the south line of the railroad at Rodeo. There has been considerable mining at several places north and south of Steins. The Carbonate mine, about 3 miles south, is on the eastern slope of the Peloncillo Mountains. These mountains, made up of lavas, form a long, narrow ridge which extends far to the north and south along the western margin of New Mexico. The jagged crest line presents many conical peaks, each resembling a pelón (Spanish for a cone of raw sugar). Peloncillo (pay-lone-see'yo) is the diminutive form of pelón.

The gap through which the railroad crosses this range is known as Steins Pass, but the divide is at Steins station, a short distance east of the rocky gateway. The pass has high walls on the north side and rocky slopes to the south, all consisting of lavas that were erupted in early Tertiary time, part of a succession of flows 1,200 feet or more in thickness which have been tilted gently to the north and northeast; on the east are two old volcanic cones from which doubtless some of the lava flows originated. In the large stone quarry in the north wall of the pass a contact of two flows of the lava (andesite on rhyolite tuff) is strongly marked by difference in color. Here both rocks have been quarried for ballast for the railroad and for other uses. In the quarry a dike cutting the lava is well exposed. Vertical jointing is a very conspicuous feature, especially on the west slope of the mountain.

From Steins Pass there is a magnificent view to the west across the wide San Simon Valley (see-moan') to the Chiricahua (an Indian name pronounced nearly like cheery cow) and Dos Cabezas Mountains, which are separated from each other by Apache Pass. In the high crest of the Chiricahua Mountains is a profile of a huge face directed skyward, known as Cochise Head, from the famous Apache chief Cochise (co-chee'say). The prominent straight nose is easily recognized; the chin is to the north.

Steins Pass has long been an avenue of access into eastern Arizona by way of the San Simon Valley and thence west by Apache Pass or by Railroad Pass at the north end of the Dos Cabezas Mountains.

This region with its wide adjacent valleys was the scene of many Apache depredations in the early days of travel and settlement. Much blood was shed during Cochise's outbreak, especially when the frontier troops were called east for the Civil War. The stages then ceased to run, and a large proportion of the white settlers left the country. Many persons were killed. The Apache Indians raided ranches, mines, and travelers, sallying forth from hiding places inaccessible to riders less skilled than themselves, where a few Indians could resist many times their number. They were difficult to fight, for they avoided open engagements and could travel fast and far on their ponies. It is stated that Cochise's enmity was aroused by an act of treachery of an inexperienced young Army officer who, when Cochise, under a flag of truce, came to deny that his tribe had abducted a white child, seized him and a group of his chiefs. Cochise escaped, but his chiefs were hanged. This was in 1860. It was Gen. O. O. Howard who 12 years later finally arranged a peace pact with Cochise, a treaty which the chief required his band to observe until his death in 1874.

In the Chiricahua Mountains is a great cavern where the remnants of Cochise's band had the custom of gathering after his death to honor him with weird ceremonies. These mountains were also the headquarters of Arizona Kid, one of the last of the bad Apaches.

The Chiricahua Apaches were repeatedly placed on reservations, but they were subject to a vacillating Federal policy, with the result that they went on the warpath at frequent intervals. Chato, Gerónimo, Nachi, Loco, and Victorio were notorious chiefs. On his last escape from the reservation in the White Mountains, Geronimo and his band, slaughtering people as he went, traveled south along the New Mexico-Arizona line as far as Steins Pass. Here he turned west to a hiding place in the Chiricahua Mountains. After 10 years of this warfare the Apaches were subjugated in 1886 by Gen. Nelson A. Miles, and their leaders removed from the territory.11

11Victorio, after various raids and atrocities in Mexico, Texas, and Arizona, was killed in 1880, when with 98 of his band he was attacked by Mexican troops at Tres Castilos, Mexico. It is said that his scalp was exhibited in Mexico City. Nachi was Cochise's son.

Gerónimo (Spanish for Jerome), who was particularly notorious, was born about 1834 on the San Francisco, a branch of the Gila River in western New Mexico, and died in captivity February 17, 1909. His real name was Goyathlay ("one who yawns"). In 1876 he and other Apaches fled to Mexico to avoid being moved to San Carlos, Ariz., but he was recaptured. In 1882 he left San Carlos on a raid into Sonora but surrendered to Gen. G. H. Crook in the Sierra Madre and settled on his fine farm in San Carlos. In 1884-85 he made a bloody raid through southern Arizona and New Mexico into Mexico, where in August, 1886, he and Nachi (his chief, son of Cochise) and their band of 340 were captured by General Miles and sent to Florida and finally to Fort Sill in Oklahoma. He died there Feb. 17, 1909 (Hodge, F. W., Handbook of American Indians: Bur. Am. Ethnology Bull. 30, p. 491, 1912).

| Arizona. |

At Cavot siding, 4 miles west of Steins station, the State of Arizona is entered. The State line is on the thirty-second meridian west of Washington (very nearly 3 miles west of longitude 109° west of Greenwich) and was so defined by law when the Federal Government was attempting to establish an initial meridian passing through the National Capital. Most of its western boundary is formed by the Colorado River, and its average width is about 315 miles. With an area of 113,956 square miles, it is the fifth State in size in the Union, being nearly as large as New York and New England combined. Arizona is a region of vast plateaus, in larger part from 5,000 to 8,000 feet above sea level, numerous ridges and mountains, some of them reaching more than 12,000 feet, and many wide desert valleys. The highest point is San Francisco Peak, north of Flagstaff, elevation 12,611 feet; the lowest point is on the Colorado River below Yuma, about 70 feet. On account of its great width from north to south and its range in elevation the State presents wide diversity of climate, with extremes in the low hot regions near Yuma and the cold forested mountains in the north.

Although the agricultural resources of Arizona are not developed to their full possibility, even where water is available for irrigation, the farm products for 1929 were valued at $50,544,000 and for 1930 at $37,000,000. The area cultivated, most of it irrigated, was about 650,000 acres,12 or less than 1 per cent of the area of the State. The number of farms in 1929 was 8,523. Of. the total area, 10,526,627 acres, or 14-1/2 per cent, is in farms or ranches, and their value in 1930, including buildings and machinery, was $194,644,470. Nearly 22,000 acres is in fruit trees. In 1929 the cultivated hay crop had a value of $5,745,444, and wheat and other grains $2,061,808. In 1930 cattle numbered 695,118, with large yield of dairy products, and sheep and goats numbered 1,630,853 and yielded nearly 6,200,000 pounds of wool and mohair, which sold for more than $1,600,000. Fruits of citrus and deciduous trees, a comparatively new source of income in Arizona, reached a value of nearly $2,000,000 in 1928. Cotton and corn are being more and more cultivated as new lands are brought under irrigation. In 1929 211,178 acres was in cotton, yielding 149,488 bales, valued at about $15,000,000. Some of the cotton is of the long-staple variety, averaging 1-5/8 inches long, which is in great demand for automobile tires. This variety was developed from the Mitafifi stock brought from Egypt by the United States Department of Agriculture about 1900.

12These figures and the following statistics as to farming, livestock, and timber are taken from the reports of the Fifteenth Census of the United States.

Arizona is second to California in the production of lettuce, especially the "Iceberg" variety, which yields two crops a year. Timber has been an important industry for 40 years, with a cut of 160,000,000 board feet in 1929, valued at nearly $5,000,000. The remaining timber, of which there is a vast area with a growth estimated by the United States Forest Service at over 14,000,000,000 board feet, is mostly in national forests, where it is cut under supervision and brings a good revenue to the United States.

Mining has always been the chief industry of the State, and it is estimated that 25 per cent of the adult population is connected with this industry. The total output up to 1929 had a value of about $2,500,000,000, and $37,000,000 has been paid in dividends by certain large mines (Yearbook of Arizona, 1930). Copper is the chief product, coming mostly from mines at Bisbee, Jerome, Globe, Miami, and Ray. According to the United States Bureau of Mines, the total output of the State to the end of 1929 was 13,914,970,235 pounds, making it the largest copper-producing region of the world. Arizona now supplies 46 per cent of the United States output of copper and 22 per cent of the world's product, or slightly less than South America. Most other common metals are also produced. Many old mines have been abandoned, but new developments are constantly in progress. The Bureau of Mines states that the value of the principal metals produced by mines in Arizona in 1929 was about $158,433,300. Owing mainly to greatly reduced production, but partly to the lower price of most of the products, the value dropped to half of this amount in 1930 and to less than a quarter in 1931. In 1929 gold was mined to a value of about $4,217,000,13 silver $3,875,000, copper (833,525,000 pounds) $149,200,000, lead $984,250, and zinc $156,800. The year 1929 was the most prosperous since 1918, and the sum paid in dividends that year was the largest on record, but in 1931 the gold output decreased to about $2,554,000, silver to about $915,500, and copper to about $33,000,000 (Bureau of Mines). Altogether the mines of Arizona have yielded profits in excess of $500,000,000 (Yearbook of Arizona, 1930). A large amount has been spent in prospecting and unprofitable mining.

13Gold has a fixed value of $20.671835 an ounce for "fine" or pure gold.

According to the Yearbook of Arizona for 1930, the assessed valuation of property in Arizona in that year was $714,945,809. There are more than 2,500 miles of railroad lines in the State.

With a population of 435,573, according to the census of 1930, or 3.8 persons to the square mile, Arizona is one of the most thinly populated of our Western States. The increase in population from 1920 to 1930 was 30.3 per cent, or much greater than in most other States. According to the report of the Commissioner of the General Land Office for 1930-31, of its 72,838,400 acres there remains 14,366,400 acres of public land, but a very large part of this area is not suitable for agriculture. About half of this public land is not yet surveyed. Nearly 2,000 square miles is included in Indian reservations and national forests. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs, in his report for 1932, gives the Indian population as 48,162, or about 14 per cent of the total number of Indians in the United States. Of these nearly 25,000 are Navajos, nearly 6,000 Apaches, about 5,000 Pimas, and about 5,000 Papagos.

There are many indications of the presence of prehistoric aborigines in Arizona, for on plains, on mesas, and in the cliffs there are ruins of their habitations, some of them very old. However, it is believed that the number of people living in the region at any time may never have been great, for they moved from place to place, abandoning their communal or village dwellings. The early expeditions of the Spanish explorers found many pueblos, but they were widely scattered. It is probable that the first Spaniards to enter Arizona were the Franciscan friars, Juan de la Asunción, Juan de Olmeda, and Pedro Nadal, who made an exploration in 1538 from Mexico City "1,700 miles northwest to a broad, deep river" which they could not cross—perhaps the Colorado. In 1539 Marcos de Niza, another Franciscan friar, crossed southeastern Arizona from Sonora on the way to Zuñi. A year later De Niza led Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to Zuñi. Coronado had an advance escort of 50 horsemen, some natives and a group of friars, followed by his main army of 250 adventurers, including many Spaniards of high rank, and some 800 Indian allies. Two small parties from Coronado's expedition visited the Hopi pueblos, and they were also reached by Antonio de Espejo in 1583. Hernando de Alarcón explored the Gulf of California and lower Colorado River in 1540, and Juan de Oñate visited part of the same region in 1604-5. It was Oñate who in 1598 took possession of "all of the country north of New Spain" and called it Nuevo Méjico. In 1691, Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit priest, began his missionary work in Arizona, visiting settlements in the Santa Cruz, San Pedro, and Gila Valleys and supplying the Indians with livestock. He laid the foundation of the mission church of San Xavier at Bac, 9 miles south of Tucson (too-sown'), in 1700 and of San Gabriel at Guevavi, near Nogales, in 1701. He made numerous expeditions, reaching the Colorado River near Yuma in 1699 and again in 1700. He crossed the river below that place in November, 1701, and reached its mouth in March, 1702. The expedition of Father Jacobo Sedelmaier in 1744 followed the Gila River (he'la) below Casa Grande and traversed the region west and south to Yuma, discovering the warm springs at Agua Caliente. Father Francisco Garcés, a Franciscan who labored for 12 years as a missionary to the Indians, made notable expeditions from San Xavier in 1768 to 1775 into southwestern Arizona and southern California. He was killed at Yuma in the Indian revolt of 1781. (See p. 237.)

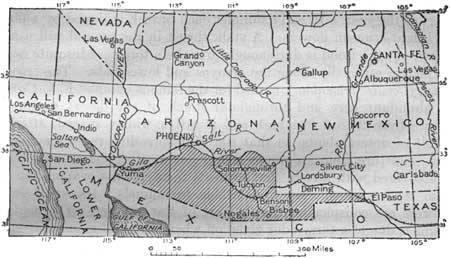

After Mexico won her independence from Spain in 1822 the region made but little progress, and when in 1827 the order of expulsion against the Spanish caused most of the friars to leave, many of the little settlements were abandoned. The country north of the Gila River was ceded to the United States by the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. Prior to that there were no American inhabitants in the territory. Most of the early visitors were prospectors, thousands crossing during the gold rush to California in 1849. After the Gadsden Purchase (see fig. 35), by which over 45,000 square miles south of the Gila River was acquired through an expenditure of $10,000,000 in 1854, several Governmental surveys were made across the region, mainly to find routes for railways. For a long time the principal access to Arizona was by water, ships from many ports coming into the Colorado River. Mail and passenger stages from the East (see pp. 97, 125) ran from 1857 to 1861 and again from 1867 till superseded by the railroads. The Southern Pacific line was constructed in 1879-80 from Yuma eastward to the Arizona State line, whence it was completed eastward to El Paso by the following year. (See p. 293.) From 1847 to 1860 many mines were opened and placers operated, more or less under protection of the Government. In 1860 the white population was less than 5,000. The outbreak of the Civil War and the withdrawal of troops gave the Apaches and white outlaws increased opportunity for depredations. Many settlers were killed at this time, most of the mining was discontinued, and nearly all who could do so left the country. A small band of people fortified themselves in Tucson, which was taken by the Confederates in 1862 and held until Union troops, known as the California Column, came from California. After the war also there was much bloodshed by Indians, who killed about 400 settlers and 150 soldiers in the interval from 1866 to 1886, when the Apaches were finally subjugated. The difficulties with these Indians greatly retarded the development of Arizona, for they kept out prospectors and settlers, interrupted travel, and frightened investors.

|

| FIGURE 35.—Map showing the Gadsden Purchase (shaded area) acquired from Mexico in 1854 for $10,000,000 |

Originally Arizona was part of New Mexico, but on February 24, 1863, it was made a separate Territory of the United States and formally organized at Navajo Springs. Until 1871 it included the triangular area now constituting the south end of Nevada, named Pah-Ute County, which was separated by act of Congress in 1865. The name Arizona is supposed to have been taken from Papago words that signify place of small springs. According to Cavat and Mora, however, it is derived from an ancient Pima name first applied to a mining camp in Sonora. It was used by the Spaniards as early as 1736. The capital has been successively at Fort Whipple, Prescott, Tucson, again at Prescott, and since 1889 at Phoenix. Statehood was attained February 14, 1912. The Southern Pacific Railroad was built through Arizona in 1880 and the Atlantic & Pacific (now a part of the Santa Fe system) in 1883. The first train entered the State at Yuma in September, 1877. (See p. 292.)

As the tracks wind down grade from Steins Pass, there are in view many plants of the curious-looking ocotillo (o-co-tee'yo), Fouquieria splendens (see pl. 41, A), which prefers the rocky soil of the foothills. It consists of a cluster of nearly straight, slender stems diverging upward, covered with thorns and bearing very small leaves during part of the year. In early summer each branch is tipped by a plume of bright-crimson flowers. A stalk thrust in the ground will usually grow, yet the wood is dry enough to make a torch. Mesquite occurs in places, especially along the arroyos and lower fiats. The creosote bush (Covillea tridentata), named for the famous botanist F. V. Coville, is abundant here and throughout much of the desert region. It grows from 2 to 6 feet high and is rather widely spaced, after the habit of desert plants, so that the wide-spreading roots may gather the moisture from an ample area. For most of the year its leaves are covered with a resin that protects them against evaporation and also renders them very unpalatable to animals. Its small yellow flowers are conspicuous during part of the summer. The common name is due to a tarry odor given off when the plant is burned.

|

San Simon. Elevation 3,613 feet. Population 300.* New Orleans 1,370 miles. |

Ten miles beyond the State line is San Simon, the center of a small irrigation district using water from artesian wells. It is in the bottom of the wide San Simon Valley, which lies between the Peloncillo Mountains on the east, the Chiricahua and Dos Cabezas Range (dose ca-bay'sas) on the southwest, and the Pinaleño Mountains (pe-na-lane'yo) on the northwest. It is drained by San Simon Creek (usually dry), which empties into the Gila River 50 miles to the northwest. All the watercourses crossed by the north line of the Southern Pacific in Arizona empty into the Gila. This stream is one of the largest rivers of the Southwest and was the southern boundary of the United States before the Gadsden Purchase.

Where not irrigated the San Simon Valley is mostly a smooth plain covered with a sparse desert vegetation. It is underlain by a thick deposit of sand and gravel, which fortunately contains water available for wells. According to a report by A. T. Schwennesen the area in which artesian flows are obtained extends about 18 miles along the lower part of the San Simon Valley above and below San Simon. Its width averages about 6 miles. There is also a small, narrow area of artesian flow at the San Simon Ciénega (se-ay'nay-ga) a few miles up the valley, and an extensive area in which water is obtained by pumped wells of moderate depth. Up to 1910 the region was a range for cattle belonging to widely separated ranches using water from shallow wells. Then the discovery of water in deeper beds under sufficient head to afford artesian flow brought many agriculturists, who have utilized the water for irrigation. In 1914 there were 127 flowing wells, mostly ranging in depth from 500 to 1,000 feet and yielding from 20 to 100 gallons a minute. It was estimated that at that time the total flow approximated 15 second-feet, or 11,000 acre-feet a year. Many nonflowing wells are now pumped. The quality of the water is excellent, most of it containing only from 250 to 380 parts per million of total solids. The moderate supply of water requires careful conservation, especially to avoid waste. The water occurs in gravel interbedded in light-colored clay and sand, which have been penetrated to a depth of 1,230 feet. These beds are overlain by a thick body of blue clay which holds the water down. The source of supply is rain that falls on the sides and upper part of the valley. The region has an arid climate, with a mean annual precipitation of less than 7 inches at San Simon; at Bowie, however, it is nearly 14 inches, a difference probably due to the proximity of the Dos Cabezas Mountains, in which the precipitation is estimated as near 20 inches. At Paradise, in the Chiricahua Mountains, it is 18 inches.

Originally the San Simon Valley was grassy, and the broad flats were covered with a coarse, high grass known as sacaton (sa-ca-tone'). With the extension of cattle grazing this was largely eaten out, but in rainy seasons the lower parts of the area had considerable small grass, and grama and other grasses grew in fair supply on the higher slopes. Since the advent of settlers erosion has cut deeply into the valley bottom, and many wide gullies and bare areas have resulted.

In the west slope of the Peloncillo Mountains, about 10 miles northeast of San Simon, are very small deposits of "saltpeter," or potassium nitrate, in rhyolite tuff, which have been prospected to some extent. It has been found, however, that the material is only a surface impregnation in crevices and under overhanging cliffs. Probably it has been formed through the action of bacteria on organic matter in places where the air has access and where the associated rock is sufficiently porous to permit the percolation of water, which would be concentrated by evaporation. The mineral occurs in this manner in many caves and places protected from the rain wash in the West and generally gives rise to the false hope that valuable nitrate deposits may be found.

The Chiricahua Mountains, which culminate in the peak known as Cochise Head (elevation 8,100 feet), are 15 miles south of San Simon. They consist largely of a thick succession of volcanic rocks of Tertiary age similar to those of the Peloncillo Mountains. Here, however, it may be seen that these rocks mantle an older mass of Paleozoic sandstones and limestones, in part overlain by sandstone, limestone, and shale of Lower Cretaceous age (Comanche series.)14 In one area the intrusion of igneous rocks has changed the limestone to marble, which has been quarried to some extent. Blocks of this material lie along the railroad at Olga, a siding halfway between San Simon and Bowie. The deeper canyons in the mountains reveal a basement granite or schist of pre-Cambrian age. These mountains sustain a growth of pine on top and are part of the Coronado National Forest, which includes five timbered ranges in this general neighborhood. (Turn to sheet 21.)

14The succession of strata in the Chiricahua Mountains is as follows: Sandstones and limestones (Comanche series); limestones of Carboniferous and Devonian age; slabby limestone (Abrigo) of Upper Cambrian age; and sandstone, in part quartzitic (Bolsa) of Upper Cambrian age. (See p. 175.) The general structure is anticlinal, but the arch is broken by faults. Porphyritic rocks of igneous origin cut some of the strata.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/845/sec20.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2007