|

Geological Survey Bulletin 845

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part F. Southern Pacific Lines |

ITINERARY

|

|

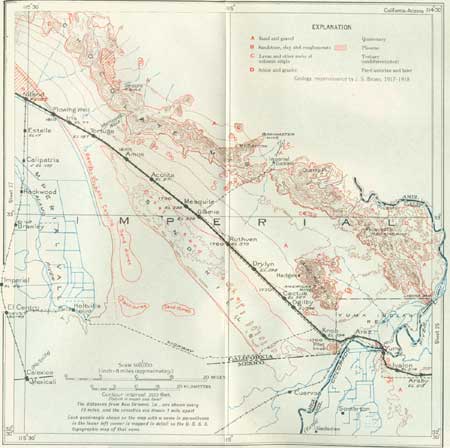

SHEET No. 26 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

YUMA, ARIZ., TO LOS ANGELES, CALIF.

| Colorado River. |

The Colorado River is crossed on leaving Yuma. This great river rises in the mountains of Colorado and after its junction with the Green River from Wyoming it receives the drainage of a wide area in the high plateaus of Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona. It was discovered by Francisco de Ulloa, who in 1536 ascended the Gulf of California to the great mud flats at the mouth of the river. In 1540 it was explored by Melchor Díaz, who traveled overland from Sonora, Mexico, to the vicinity of Yuma, and by Hernando Alarcón, who came in boats from western Mexico and ascended the river for 15 days, possibly as far as Needles. Early in 1605 Juan de Oñate reached the river in the vicinity of Yuma on a trip from Santa Fe. Owing to the custom of the natives of carrying firebrands in winter with which to warm themselves, Díaz named the stream Río del Tizón (Firebrand River), a name more distinctive than the present one. The name "Rio Colorado del Norte" was first used on Kino's map in 1701. He reached it first in 1699. Padre Sedelmaier was there in 1744. The Franciscan friar Francisco Garcés, traveling alone, reached the Colorado in 1771 near Yuma and crossed it on a raft. He crossed it again at that place in 1774 and 1775 with Anza's expeditions.

In the vicinity of Yuma, as elsewhere, the Colorado River meanders through a shallow channel in a wide trench excavated in the great desert plain that extends to the Gila Mountains on the east and constitutes the Colorado Desert and Imperial Valley to the west. The trench or alluvial flat is nearly 5 miles wide at Yuma, where it is bordered by long bluffs of sand and gravel 50 to 100 feet high. The upper part of Yuma is built on the bluff, which is here called "the Mesa." The trench also extends up the valley of the Gila River for many miles. The surface of the alluvial flat is nearly smooth, but in places it slopes slightly away from the river, owing to the low bank or levee built by the stream at times of freshet when there is considerable overflow in places not protected by artificial levees. South of Yuma there are extensive sloughs and oxbow ponds along the principal overflow channels.

The Colorado River empties into the head of the Gulf of California in Mexico about 60 miles below Yuma (see pl. 35), and in fact this large water body is an extension of the Colorado Valley submerged by tidewater. The volume of the river varies considerably, and at times it is greatly swollen by freshets. The floods occur mostly in early summer and are fed by winter rains and snows in the distant mountains. The highest summer floods have exceeded 200,000 second-feet (cubic feet per second). The ordinary maximum flow is 70,000 to 100,000 second-feet, the minimum flow, 2,500 to 3,000 second-feet, and the average 10,700 second-feet. In August, 1931, the flow at Yuma decreased to 200 second-feet (U. S. Bureau of Reclamation). The total yearly flow at Yuma averages about 16,730,000 acre-feet (1902-1916) including 1,000,000 acre-feet or more from Gila River. The mineral content of the water ordinarily ranges from 1,000 to 350 parts per million,66 and it is estimated that the sediment in suspension is sufficient to cover about 100,000 acres 1 foot deep (100,000 acre-feet) annually. Considerable sediment is also moved along the bottom of the river. The material spread on the land by overflow has important fertilizing value. (U.S. Bur. of Reclamation).67

66A very large amount of material is removed from the land and carried to the ocean by all rivers. Careful estimates based on analyses of river waters and measurements of volume of flow have shown that every year the rivers of the United States carry to tidewater 513,000,000 tons of sediment in suspension and 270,000,000 tons of dissolved matter. The total of 783,000,000 tons represents more than 350,000,000 cubic yards of rock, or a cube measuring about two-fifths of a mile on each side (1/15 cubic mile). The total is equivalent to 610,000,000 cubic yards of surface soil. (See U. S. Geol. Survey Water-Supply Paper 234, p. 83, 1909.)

67See also Bacon, J. L., Monthly Weather Review, vol. 59, pp. 295-297, 1931; Breazeale, J. F., Arizona Univ. Bull. 8, 1926; Forbes, R. H., Arizona Univ. Bull. 44, 1902.

|

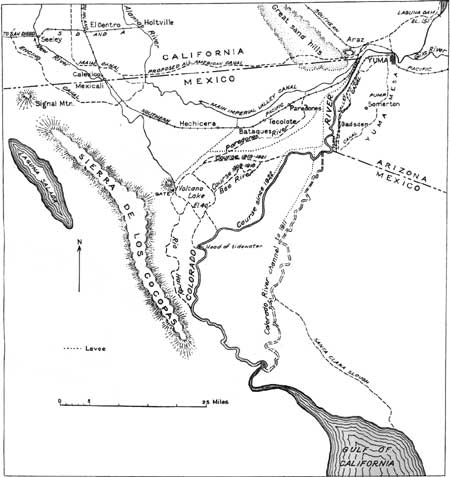

| PLATE 35.—MAP OF THE COLORADO RIVER DELTA REGION, BELOW YUMA, ARIZ. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

An important engineering project in connection with the Colorado River is the Boulder Dam, in Black Canyon, 200 miles above Yuma (about 15 miles below Boulder Canyon), which was started in 1931. It will completely control the waters of the river and not only maintain the supply as needed, but prevent floods and greatly diminish the amount of silt. According to printed statements of the United States Bureau of Reclamation the dam will be a curved gravity structure about 1,180 feet long and will contain approximately 3,500,000 cubic yards of concrete requiring about 5,500,000 barrels of cement. Its height will be 707 feet above bedrock; this will raise the water surface about 582 feet, or to 1,229 feet above sea level. The reservoir, 115 miles long and with an area of about 145,000 acres (227 square miles), will hold 30,500,000 acre-feet of water. It will take a year and a half for the river to fill the reservoir under ordinary conditions of flow. The cost of the dam will be about $7,600,000, not including a 1,200,000-horsepower electric generating plant ($38,000,000), the revenue from which, together with the charge to irrigators for the water, is expected to cover the interest and finally repay the cost. An all-American canal 75 miles long, provided for by an allotment of $38,500,000, will be built through the sand hills that begin 10 miles west of Yuma, to replace the present canal, which for 35 miles is in Mexico. Its cost also must be repaid by the irrigation under it. This canal, with a bottom width of 134 feet and a depth of 22 feet, will supply a much larger volume of water than is now flowing in the old canal, which is the largest one in operation in this country, and will provide for greatly increasing the irrigated area in Imperial Valley. The water will be taken from the river at a point 5 miles above the present Laguna Dam, a few miles above Yuma. It is estimated that a branch 130 miles long to provide for irrigation in the Coachella Valley and increasing the area irrigable under this project to 900,000 acres, will cost about $11,000,000. Los Angeles will also receive some of the water (1,500 second-feet), which will be taken out at Parker and carried through long aqueducts and tunnels by way of San Gorgonio Pass.

From a point 6 miles west by south from Yuma the middle of the Colorado River is the boundary between the United States and Mexico, Arizona extending about 16 miles farther south than California. By the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in 1848, the original international boundary followed the Gila River to its junction with the Colorado and thence was a straight line west to a point on the Pacific Ocean 1 marine league south of the southernmost point of the port of San Diego. By the Gadsden Purchase the southern boundary east of the Colorado River was shifted to its present location, which touches the Colorado at a point 20 English miles below the junction of the Gila. North of Yuma the Colorado is for many miles the dividing line between Arizona and California.

| California. |

California, the largest of the three Pacific Coast States, has a length of 780 miles and width of about 250 miles. The area is 158,297 square miles, nearly equal to New York, New England, and Pennsylvania combined. The population of California in 1930 was 5,677,251, or about one-fifth of that of the Eastern States named. This was a gain of nearly 66 per cent in the 20 years from 1910 to 1930. The average number of persons per square mile was 36.5, as compared with 22 in 1920. The population is very unevenly distributed, however, the desert regions east of the Sierra Nevada being very sparsely occupied. The State has 1,264 miles of coast line, mostly bold and unbroken but indented by the fine harbors of San Diego and San Francisco.

California has a great range in elevation, for some of its desert valleys are below sea level and much of the Sierra Nevada is more than 10,000 feet above sea level, the highest peak, Mount Whitney, reaching 14,496 feet. The lowest places are Death Valley, the bottom of which is 276 feet below sea level, and the Salton Basin, the bottom of which (when dry) is 273.5 feet below sea level. Owing to its great range of elevation and latitude, California presents a wide diversity in climate, with corresponding variation in vegetation and animal life. Along the coast in southern California precipitation is low and temperatures are equable. Around San Francisco Bay the moderate rainfall comes almost wholly in the winter, and the seasonal range of temperature is comparatively small, although from hour to hour the change is sometimes very marked. In parts of southern California typical desert conditions prevail. The great interior valley of the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers is characterized by moderate to scant winter rainfall and hot, dry summers. Snow rarely falls except on the adjoining high mountains.

Forests cover 20 per cent of the State. They are notable for the large size of their trees, especially for the huge dimensions attained by two species of redwood—Sequoia washingtoniana (or S. gigantea), the well-known "big tree" of the Sierra Nevada, and Sequoia sempervirens, of the Coast Ranges. Some of these giant trees have fortunately been preserved against the inroads of the lumberman by the Government or through private generosity. The 21 national forests in California have a total area of 40,000 square miles, or about one-fourth of the State's area. The national parks in the State are the Yosemite (1,124 square miles), Sequoia (252 square miles), General Grant (4 square miles), and Lassen Volcanic (124 square miles).

Agriculture is an enormous industry in California, and its importance is increasing. The following facts from the United States census reports are of interest: Of the total land area of nearly 100,000,000 acres, about 30,442,581 acres is in farms and ranches, which with buildings and machinery have a value of nearly $4,000,000,000. More than 4,000,000 acres is under irrigation. The value of crops in 1929 was $623,103,467, the cost of which for labor and fertilizer was $212,417,664. The grain crop in 1929 was 48,451,246 bushels, of which about three-fifths was barley. The cultivated hay crop for 1929 was 4,098,993 tons, and the cotton production 253,881 bales. In the variety and value of its fruit crops California outranks all other States. Its products range from dates, figs, pineapples, and other semitropical fruits in the south to pears, peaches, apples, and plums in the north; but it is to oranges and other citrus fruits and grapes that California owes her horticultural supremacy. During 1929 California produced 53,820,634 boxes of citrus fruits, 37,738 tons of walnuts, 4,700 tons of almonds, 1,691,111 tons of grapes, of which more than half were of the raisin variety, and great quantities of prunes, peaches, apricots, olives, and melons. Other notable crops are hops, about 7,905,965 pounds in 1929; lima and other beans, 5,526,351 bushels; sugar beets, 452,818 tons; potatoes, 6,489,203 bushels; and wheat, 10,957,967 bushels. The total value of vegetables shipped in 1929 was about $60,272,659. More than 5,000 acres is in strawberries, and the fig crop in 1929 was more than 59,000 tons. California leads in apiculture, producing about one-tenth of the Nation's honey, the amount being normally about 6,000,000 pounds, besides 300,000 pounds of wax. Much honey is exported from Los Angeles. There are about 150 species of plants that furnish nectar in important amounts; the blossoms of oranges and sagebrush are the most reliable sources. The yield of honey is closely related to the amount of rainfall. Many of the bee colonies are moved from place to place to take advantage of blossoming periods, not only for the honey obtained but for service in pollenization. Dairying is an important industry, with a yield of 445,530,000 gallons of milk in 1929. In 1930 the wool clipped amounted to 18,747,453 pounds. Cotton, melons, and dates are raised abundantly in the irrigated districts in the southeast corner of the State, and rice production is increasing rapidly.

Of its mineral products, petroleum ranks first in total value, and gold next. According to the United States Bureau of Mines, California's output of petroleum was 227,329,000 barrels in 1931 (292,036,911 barrels in 1929), about 16 per cent of the world's yield, and its output of gold amounted to about $8,455,200. Other mineral products are cement, 13,091,899 barrels; copper, 33,084,232 pounds; silver, $636,749; mercury, 10,139 flasks (of 76 pounds); and borate minerals, 169,870 tons, valued at $4,515,375. The total value of products from California mines and quarries in 1929 was $38,645,889, with a personnel of more than 9,000. The leading industry is refining petroleum, the products of which in 1927 were valued at more than $350,000,000. California's fisheries are also a source of much revenue. According to the United States Department of Commerce, the exports from San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego had a value of $377,392,437 in 1929, and the annual imports amount to nearly $300,000,000, of which more than half passes through San Francisco. There are in the State four great universities—the University of California (enrollment 19,000), Leland Stanford Junior University (4,600), the University of Southern California, and the California Institute of Technology—besides many smaller collegiate institutions.

The recorded history of California began in 1542, when Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo explored the southern coast. Sir Francis Drake, who landed on California soil in 1579 to repair his ships, named the place New Albion, but later the name California was applied. It is claimed that this name was derived from Califa, queen of the Amazons, used by Montalvo in a romance, but also that it was taken from the name given by Cortez to the south end of Lower California and meaning fiery furnace. Until Padre Kino's explorations in 1700 and 1701, California was supposed to be a island. In 1602-3 Sebastian Viscaino discovered the sites of San Diego and Monterey. From 1769 to 1823 21 missions were established in California under the direction of the Franciscan friar Junípero Serra and other missionaries of his order, and most of them still remain, although some are in ruins. The first overland caravans to California began in 1827, and the discovery of gold by J. W. Marshall at Sutter's mill in 1848 brought a large influx of gold seekers and settlers.68

68The first discovery of gold was made in Placerita Canyon, near Los Angeles, in 1842, but it had little economic importance.

California was formerly a part of Mexico, but many citizens of California were Americans and strongly desirous of entering the Union, especially as trouble with Mexico increased. On July 7, 1846, the American flag was raised in Monterey, and the annexation of California proclaimed. The treaty of Cahuenga, negotiated by Gen. John C. Frémont and the Mexican commander, Andrés Pico, and signed on January 13, 1847, ended hostilities, and in 1850 California was admitted to the Union as the thirty-first State. The official State flower is the California poppy (Eschscholtzia californica), and the State's motto, "Eureka," means "I have found it."

On leaving Yuma the railroad crosses the Colorado River on a long bridge (see p. 236) and curves around to the northwest to traverse the alluvial plain of the river, here nearly 5 miles wide. This land is included in the Yuma Indian Reservation, 8,350 acres in all, which is supplied with water for irrigation by a canal from the Laguna Dam, 10 miles above Yuma. (See p. 238.) This canal, crossed not far beyond the river bridge, was one of the early irrigation projects of the United States Bureau of Reclamation, having been completed in 1909. About 1,500 acres is under cultivation, yielding crops of various kinds, notably cotton, which thrives on the rich sandy soil. Much alfalfa is also raised. A view of part of the irrigated district is shown in Plate 34, B. The Indians who occupy this reservation form a picturesque element among the various people who make up the population of the Yuma region. Usually the day trains in Yuma are met by Indian women offering beads and other trinkets. The Yuma Indians have cultivated the river flats for many centuries but retain many primitive methods. The Fort Yuma Indian School, a prominent building on the farther bank of the river, has an attendance of about 200. A statue of Garcés in front of the chapel here commemorates the heroic Franciscan who, after martyrdom at his mission here in 1781, was interred with respect by the Indians who had murdered him. His body was later transferred to Mexico. (See p. 187.) Kino estimated that there were 6,000 Yuma families. It has been estimated that there were 3,000 Indians here in 1853; in 1932 there were 842 under the Fort Yuma Agency. The word Yuma, from "Yahmayo," son of the captain, was applied erroneously by the early Spanish missionaries; the Indians call themselves Kwichán.

|

Araz. Elevation 156 feet. New Orleans 1,756 miles. |

A mile west of Araz siding the San Diego & Arizona Railway, a part of the Southern Pacific system, branches to the southwest and goes by way of Mexicali, Calexico, and El Centro, across Imperial Valley, and through the beautiful Carrizo Gorge to San Diego. (See p. 287.) Near Araz the railroad reaches the western edge of the river flat and begins an ascent of about 150 feet onto the higher terrace or general desert level. On this grade it passes through long, deep cuts exhibiting the nature of the sand and gravel deposits that make up the terrace. At one point this material is extensively quarried for road making. Half a mile beyond the siding, on the south side of the highway, south of the tracks, are the ruins of the old Araz stage station on the river bank, constructed in 1856. The material is adobe.69

69In the West the term "adobe" (colloquially "doby") is commonly used both for the sandy clay from which these sun-dried bricks are made and for a structure made of them.

From a point near this place a branch road follows the west side of the Colorado River, which here makes a great bend to the south and in less than 3 miles enters Mexico near the village of Algodon.

Southwest of Araz siding is the isolated Pilot Knob, or Cerro de Pablo, near the west bank of the river, consisting of a mass of lava lying against granite and schists. Near it in 1780 was established the mission of San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicñuer under the administration of Padre Garcés. The colony consisted of 20 settlers, 21 soldiers, and 12 laborers, with their families. In the Indian revolt of the following year two resident missionaries and practically all the soldiers and colonists were clubbed to deaths and the women and children were made captives. On the slope of Pilot Knob during the gold rush of 1849 a stone structure called Fort Defiance was built by Americans in connection with a ferry across the river near by. It was soon abandoned after a massacre by the Yuma Indians.

|

Ogilby. Elevation 356 feet. New Orleans 1,776 miles. |

As the level of the general desert plain is attained near Knob siding many prominent mountains come into view—the rough ridges of the Cargo Muchacho Mountains near by to the north, a group of high ridges surrounding the sharp Picacho Peak to the northeast, and various high ranges back in Arizona. Some of these mountains consist in whole or in part of volcanic rocks; others are made up of old gneisses and granites, such as constitute the Gila Mountains. A group of rocky knobs of vesicular lava, skirted 2 miles southeast of Ogilby siding, has been a source of railroad ballast. On approaching Ogilby the Cargo Muchacho Mountains seem near. They consist of schists and include a number of mines, old and new. The principal old one, the American mine, was worked from 1879 to 1918, with a production locally estimated at several million dollars. Near by are the ruins of Tumco (formerly Hedges), a town which had a population of nearly 1,000 when the mines were operating. The ore was in veins in pegmatite, which cuts the schist in every direction.

Three miles north of Ogilby is a mine producing cyanite, a very refractory aluminum silicate that is useful in the manufacture of high-grade porcelain ware, electrical insulators, and refractory brick and shapes for the glass and iron industries. This mineral, which is of a beautiful blue color, occurs in a large vein with quartz, in mica schist. It is shipped to Los Angeles for the separation of the quartz and preparation for the market.70 A mile north of the cyanite mine talc is mined, for use largely in paper manufacture.

70Cyanite is of the same composition as andalusite and sillimanite, consisting of alumina 62.85 per cent and silica 37.15 per cent, the proportion of alumina being considerably greater than in clay. The separation of the fibrous cyanite from the quartz is effected by an ingenious process of heating to 1,800° F. and chilling in water, which shatters the quartz so that it can be removed by washing and screening.

West of Knob siding and extending from the Mexican boundary to and beyond Amos siding, a distance of 50 miles, is a wide belt of sand hills which is more familiar to most persons than they are aware, for it has afforded the background for many "Sahara Desert" scenes in the moving pictures. The belt is about 5 miles wide, It presents a picturesque succession of shifting dunes, of loose pale-yellow sand, in places 200 to 300 feet high, separated by irregular basins. The highway to El Centro formerly passed over this sandy strip on a road made of heavy planks strung together with wire. It was 10 feet wide, with passing places at intervals. In 1928 this unique roadway was displaced by a wide concrete highway suitable for the present heavy traffic of Imperial Valley. This sand-dune belt is one of the largest inland occurrences of its kind in the United States. Doubtless the dunes are still shifting somewhat, but as land surveys of 1856 show practically the same configuration as the present one, the change must be slow, and probably many hundreds of centuries has been required for their accumulation. They are a serious barrier to canal construction, as the sand is loose and drifts extensively, but in 1931 provision was made to build an all American canal through them to supply water to Imperial Valley without the deflection into Mexican territory which the old canal makes.

|

Glamis. Elevation 338 feet. Population 15.* New Orleans 1,785 miles. |

From Ogilby northwestward the railroad passes between the sand hill belt and the long slopes that lead up to the mountains to the northeast. At Glamis a road to Blythe leaves the railroad and proceeds to a distant pass up the Palo Verde Valley (pah'lo vare'day), a wide dry wash which rarely carries any water. As the rainfall in this region is very low, an average of about 3 inches a year, vegetation is sparse and closely adjusted to soil conditions. Ironwood (Olneya tesota) and the creosote bush (Covillea) are the most noticeable features in the vegetation; ocotillo is conspicuous in places. Some of the ironwoods are 20 feet high, but they are widely separated. Northwestward from the gap northeast of Glamis the Chocolate Mountains71 make a high continuous wall extending for 20 miles as a succession of prominent ridges rising abruptly from the valley, 3 to 8 miles northeast of the railroad. In these mountains there have been a few notable mines, including the Paymaster and Pegleg, both of which were good producers of silver-lead ores years ago. At the east end are some outlying buttes capped by basalt, and in part of the range and in foothills on its south side are andesitic and rhyolitic lavas of Tertiary age. It has been suggested that the steep south front of the range in this vicinity was determined by a fault; granite and basalt occur in small foothills south of the main range.

71The Chocolate Mountains consist mainly of granite, but schist also occurs, and these old rocks are overlain and flanked in places by lavas of Tertiary age. In Iris Pass, which crosses the range north of Niland, there are Tertiary strata consisting of steeply tilted beds of sandstone, conglomerate, and yellow clay, lying on light-colored igneous rocks. Near the upper end of the canyon leading to this pass beds of white soft tuff give place to a vertical mass of dark rhyolitic breccia in which the canyon narrows greatly. On each side of this mass are beds of conglomerate which appear to lie nearly horizontal and contain boulders of rhyolite and other volcanic rocks. West of the pass granite is the principal rock, constituting a high rocky range. (Brown.)

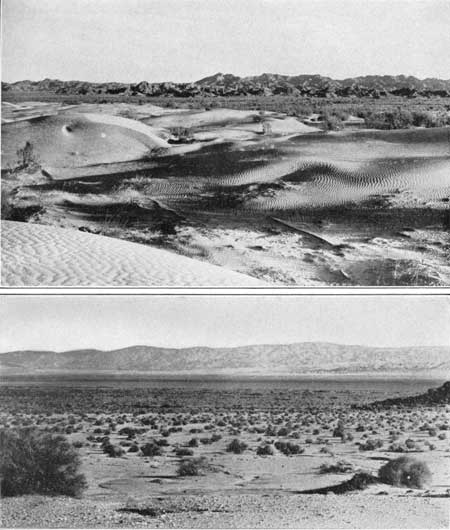

On the south side of the railroad is the great sand-hill belt (see pl. 36, A), on the farther side of which is Imperial Valley.

|

|

PLATE 36.—A (top), DRIFTING SANDS NEAR NORTH

END OF SAND HILLS NEAR AMOS SIDING, CALIF. Chocolate Mountains in

background. (Mendenhall.) B (bottom), SALTON SEA AND SALTON BASIN, CALIF. From point near Figtree John Spring, looking north to Orocopia and Cottonwood Mountains. (Mendenhall.) |

There is a down grade from a point near Glamis westward, and the tracks pass below sea level near Flowing Well siding. This place owes its name to the former presence of a marsh and a pool of brackish water of unknown origin. A short distance beyond is the East Highland Canal, which carries irrigation water along the east margin of Imperial Valley as far as Niland. From the canal crossing there is an excellent view of the beach of the old Lake Cahuilla, which once occupied the Salton Basin. (See p. 253.) The beach, which consists of sand, here forms a steep bluff about 40 feet high and extends far to the southeast along the east side of the canal.

|

Niland. Elevation -127 feet. Population 200.* New Orleans 1,815 miles. |

Near Niland outcrops of soft sandstone appear in low ridges constituting the north slope of Imperial Valley. The sandstone is interstratified with shale, clay, and conglomerate, the conglomerate mostly as a basal member. These rocks are of Miocene or Pliocene age and steeply tilted. They crop out almost continuously on the northeast side of the railroad to Indio and beyond. From Niland, formerly called Imperial Junction, a branch railroad leads south to Brawley, El Centro (32 miles), and Calexico (41 miles), in Imperial Valley. In the eastern part of Niland the railroad is crossed by the power line that furnishes electricity to Imperial Valley. The current is generated by water power in Owens Valley, 300 miles to the north. The line extends northwestward a short distance north of the railroad, to Indio and beyond.

Imperial Valley has an area of about 600 square miles, occupying the central part of Imperial County southeast of Salton Sea. Most of it lies 10 to 175 feet below sea level. The parallel of 33° north latitude passes through its center, and with the low elevation and this southern location it has a warm climate that is highly favorable for the growth of many valuable crops. With a large supply of water taken from the Colorado River and some water pumped from wells, irrigation has made this area one of the most productive agricultural districts in the world. The principal towns are El Centro, Calexico, Brawley, Imperial, and Holtville, in California, and Mexicali, in Mexico. The irrigable area is about 500,000 acres in the United States and a large district in Mexico, and at present about four-fifths of it is under cultivation. The population is about 70,000.

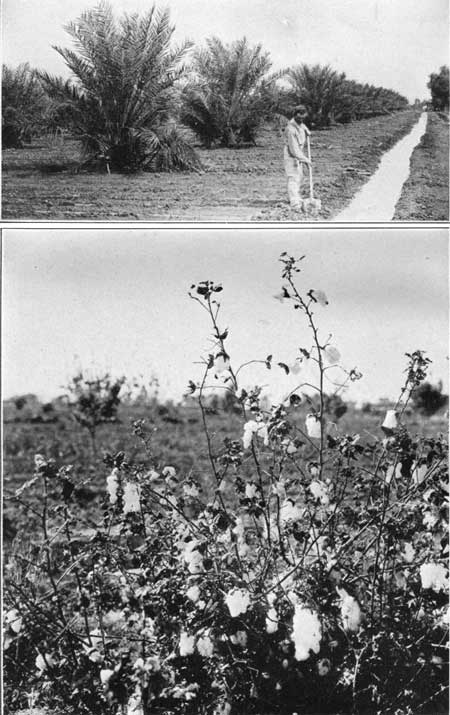

The water is taken from the Colorado River near Yuma in a large canal that passes south around the southeast end of the sand hills and then west through Mexico for about 35 miles before swinging back into the United States, which it reenters at a point south of Holtville. (See pl. 35.) The portion of this canal in Mexico is controlled by a Mexican syndicate that draws heavily on the water supply.72 In connection with the Boulder Dam project the supply will be provided by an all-American canal. (See p. 241.) The cost of the irrigation system in Imperial Valley has been about $18,000,000. The crops raised are most varied, with 112,482 acres of alfalfa, 22,165 acres of cotton (see pl. 37, B), and a large acreage of fruits and vegetables, including 8,000 acres in grapefruit and 70,000 acres in melons of various kinds. The yearly value of its products is locally claimed to be between $40,000,000 and $50,000,000. Cotton, dates, citrus fruits, barley, and alfalfa grow side by side. From Imperial Valley New York gets its earliest cantaloupes, of which it is locally estimated that about 20,000 cars are shipped each year, and 15,000 carloads of lettuce were shipped to the eastern markets in 1926. The grapefruit crop in 1929, according to the United States Census, was 329,461 boxes, and the grape crop 4,032 tons. Alfalfa yields 7 to 10 tons to the acre for each cutting, and it is harvested several times a year. Livestock and dairying are important industries which utilize the pasturage and forage products to great advantage. It is locally estimated that 16,000,000 gallons of milk was produced in 1929.

72The amount of the water of the Colorado River to be allotted to Mexico is somewhat of a problem. The American members of the International Water Commission have suggested 750,000 acre-feet a year, which is more than has ever been utilized in the area in Mexico, but the Mexican members desire nearly five times as much, or one-fourth of the total annual content of the river. In some years of scanty flow, such as 1930 and 1931, Imperial Valley could scarcely obtain a daily mean of 1,000 second-feet, although the requirements are 2,500 second-feet. (Roman, P. T., Economic aspect of the Boulder Dam project: Quart. Jour. Economics, vol. 45, pp. 177-217, 1931.)

|

|

PLATE 37.—A (top), IRRIGATING YOUNG DATE

PALMS IN IMPERIAL VALLEY, CALIF.. B (bottom), COTTON IN IMPERIAL VALLEY. |

The United States Department of Agriculture has made a detailed study of the soils of an area of 1,100 square miles in Imperial Valley, or most of that portion of the irrigable area that lies within the United States. All of the material is alluvium derived from the Colorado River, and although most of it is suitable for agriculture, some areas are too much mineralized for most plants, and others are suitable only for certain crops. Irrigation also adds to the mineralization unless precautions are taken to avoid accumulation of saline matter by evaporation, for river water contains considerable of it in solution.

Imperial Valley has a very warm climate for a large part of the year, but temperatures rarely rise above 125°, and the mean is about 70°. With very low humidity the warmth is more bearable than sultry heat in other regions. In winter the minimum has been as low as 19°, but temperatures below 32° are rare and of short duration. The mean annual rainfall is somewhat less than 3 inches. The climate in general is closely similar to that of much of the Nile Delta, but the average humidity is only about two-thirds as great and is much less variable. Dust storms, which occur mostly in February, March, and April, are short but trying.

Prof. W. P. Blake, of the Government expedition of 1853, was probably the first to recognize the agricultural capabilities of the lower part of the Colorado Desert and to suggest that the water of the Colorado River could be utilized for its irrigation. A few years later surveys were made for a canal, and in 1859 the State of California petitioned the United States Government to cede 3,000,000 acres of the land for development. In 1875-76 surveying parties reported favorably on a diversion canal passing through Mexico, on practically the present route of the main canal, but no concessions were granted, and it was not until 1900 that the canal was begun under private auspices. In 1901 water was available, and the excellent results obtained encouraged a large influx of settlers. The alluring but well-fitting name Imperial Valley was given to the region, and its development has been rapid and extensive. There were many difficulties to overcome, such as rapid silting of the canal near the headgates, but the worst setback was the breaking of the Colorado River into the intake below Yuma in 1904 and 1905. The great river, swollen by a winter flood, abandoned its own bed and flowed into the Salton Basin through the old watercourses, the Alamo and New Rivers, excavating wide channels. With this influx of the river the Salton Sea grew rapidly into a great fresh-water lake, and large areas of valuable lands and canals were destroyed. It was seen at once that unless the flow could be stopped Imperial Valley was doomed. A brush mat and piling dam was started after the summer flood had subsided, but a later flood destroyed it, and other floods added to the difficulty. Late in 1906 the Southern Pacific Co. took control of operations, and after one disheartening failure, the use of vast amounts of rock brought from quarries was effective in closing the break in February, 1907. The cost of this work was estimated at $3,000,000. The flooding of Salton Sea necessitated the removal of 67 miles of railroad tracks, in places as much as 2 miles, to their present location.

This flooding was facilitated by the high gradient of 200 feet or more in the valley, which gave the water greater declivity than its own low gradient down the old main channel to the Gulf of California. Soon the greater part of the river's flow was entering the basin, and in a year or more Salton Sea had increased in length to 45 miles and in width to 17 miles, with a depth of 67.5 feet and an area of 443 square miles. Its northwestern margin extended nearly to Mecca and its eastern margin encroached on Imperial Valley. Had the water risen much higher the great irrigation settlement would have been inundated.

When the inflow was stopped, in February, 1907, evaporation began at once to reduce the lake, and in the next five years the level fell 25 feet. This fall of 5 feet a year was less than the average annual evaporation (about 9-1/2 feet), for some water is received from the overflow and seepage of irrigation ditches and some through drainage from the surrounding mountains. In 1915 the depth of the water had diminished to 38 feet, and in 1919 to 30 feet. In the last decade the water level has ranged from 250 feet below sea level in 1923 and 1925 to 245 feet below in 1930.

Within two and one-half years after the Salton Sea was flooded its water was four times as saline as that of the river from which its water was derived. When the water receded and revealed a portion of the bottom of the basin it was found that several feet of silt covered the old salt deposit on its floor.

It has been estimated that during the time of their overflow into the Salton Basin the Alamo and New Rivers removed from their beds and banks 450,000 cubic yards of material in nine months. At this time the Alamo River developed a waterfall 30 feet or more high, which for a while cut backward at the rate of 1,400 feet a day.

Outside of the irrigated area this basin is part of the most arid desert in the country. It was called by the Mexicans and Indians "La Palma de la Mano de Dios" (the hollow of God's hand) and was named the Colorado Desert by W. P. Blake in 1853, eight years before the State of Colorado was named. At present the name Imperial Valley is used for the eastern part of the area, Salton Basin for the central area, and Coachella Valley for the upper part from the head of Salton Sea to the foot of San Gorgonio Pass. It is an inland extension to the northwest of the valley that holds the head of the Gulf of California and comprises more than 2,000 square miles between the Santa Rosa Mountains and Peninsular Range on the southwest, and the Chocolate, Orocopia, and Little San Bernardino Ranges on the northeast. It is followed for more than 150 miles by the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Structurally this area is a complex downfaulted block of the earth's crust, deeply floored by Tertiary sediments and alluvial deposits. Its lowest part is now 273.5 feet below sea level. Its main outlines apparently were developed in Tertiary time, for it contains extensive deposits of Tertiary age, and these have been flexed and faulted. They comprise Miocene or Pliocene marine beds, overlain by subaerial beds that were formed in a desert basin somewhat like the present one. Since that time, however, the basin has been greatly uplifted, for part of the Tertiary strata have been eroded down to a level far below the present valley bottom. It has been suggested that the basin was occupied until recently by an extension of the Gulf of California, which was cut off by the building of a delta by the Colorado River, but recent investigations seem to indicate that much of the present depression below sea level was effected by crustal movement after most of the Colorado River delta was built, and therefore long after the invasion by the sea. Blake discovered that in relatively recent time the basin was occupied by a transient fresh-water lake of large extent, which he called Lake Cahuilla (ca-wee'ya). (See p. 253.) The delta cone of the river, which now cuts off the basin to the southeast, is young, however, and its top is only about 30 feet above sea level. That there has been recent faulting in part of the basin is shown by a very fresh fault cliff or rift in the surface (see pl. 39) and by occasional earthquakes. As the great river carries a heavy load of sediment (see p. 240), it is reasonable to believe that it would be able to build a delta all the way from Yuma to the head of the Gulf of California at a rate equal to a slow subsidence. The salt in the present Salton Basin73 is believed to have resulted solely from the evaporation of river water and of transient streams running into the basin. The capacity of the Salton Basin up to the lowest point in the delta rim to the southeast, 30 feet above sea level, an area of about 2,100 square miles, is 264,500 square mile feet (square miles 1 foot deep). (Brown.) With an average annual flow at Yuma of 26,000 square mile feet, the water of the Colorado River, if it all entered the Salton Basin, would supply this volume in about 10 years, but evaporation would greatly retard and possibly prevent complete inundation.

73This salt was a residue left in the bottom of the basin by the evaporations of the water and was in crusts 10 to 20 inches thick; there also were layers of various thickness in the mud below. Before the inundation of 1891 salt in considerable amount was obtained at a salt works in the bottom of the basin and shipped from old Salton siding. For centuries before, however, this salt had been utilized by the Indians. The fresh waters flowing into the basin brought the salt but contained only a very small proportion, and it has been concentrated by evaporation. A 300-foot boring at the old salt works revealed 270 feet of hard clay below the salt and mud, a deposit of earlier over-flow of the basin. Emory in his exploration of 1848 found in the bottom of the basin a very shallow, highly saline pond less than 1 mile in length.

An analysis of the water of Salton Sea made by Earl B. Working in June, 1923 (Carnegie Inst. Washington Yearbook 22, p. 66, 1924), shows a concentration of nearly 39,000 parts per million of dissolved mineral matter. This mineral matter consists mainly of sodium chloride with considerable amounts of calcium, magnesium, and sodium sulphates.

Of course with continued concentration the water becomes increasingly mineralized. At the time of maximum inundation in 1907 the mineral content of the water was only about 3,000 parts per million.

The Salton Basin is in many ways similar in configuration to other closed basins in arid regions. The central portion is flat, and about its borders are alluvial slopes extending to the foot of the mountains, which rise very abruptly with steep rocky slopes. A few rocky buttes or ridges rise above the basin floor somewhat like rocky islands in the sea. The lower part of the basin is filled and floored, with a thick body of sand and silt which has been penetrated by borings, some of them 1,000 feet deep, without reaching bedrock, although they may reach formations of Tertiary age. The bottom of the basin is now occupied by Salton Sea. On the east side of the basin are the delta deposits of the Colorado River several hundred feet thick, which consist largely of fine sand and silt. Wells near Holtville are 500 to 800 feet deep in sand and gravel, the lower part of which may possibly be of Tertiary age. In the western or upper part of the basin there is much coarse material and sand deposited by streams from the adjoining steep mountain slopes. In places the sands are blown into dunes, which occupy areas of considerable extent.

The beach line of the large prehistoric water body known as Lake Cahulla74 is plainly visible at many places along the margin of the Salton Basin and extending up the Coachella Valley75 to a point about 2 miles above Indio; it extends along both sides of Imperial Valley and southward into Mexico. The surface of the water was about 40 feet above the present sea level, or more than 310 feet above the bottom of the basin. Variation in elevation of the old beach from 30 to 57 feet above sea level indicates warping of the basin in recent time. In most places the old beach forms a sandy ridge or bench only a few feet high. West of Brawley this bench is half a mile wide, and 4 miles east of Niland, near the point where it is crossed by the railroad, it attains considerable prominence, and it continues in view to a point beyond Frink. Many fossil shells of fresh-water habit (including Anodonta, Planorbis, Physa, and Tryonia) occur in the sand. Near Fish Springs, on the south side of the basin opposite Salton siding, the old strand is marked by a band of white travertine, a fresh-water deposit of calcium carbonate, on the schists. This band is very conspicuous on a projection of the mountain known as Travertine Point (pl. 38, B) and encircling an isolated hill of granite 2 miles northwest of Fish Springs. The inundation of 1907 extended to the foot of the point, covering the old trail with more than 60 feet of water, but it fell far short of the ancient lake margin marked by the travertine. Macdougal76 has estimated that the date of the last filling of Lake Cahuilla corresponding to the old beach was not more than 300 or 400 years ago. The local Indians have traditions of the lake which disappeared "poco ´ poco." Probably there were oscillations when freshets refilled it, a process which may have recurred at various times while the delta was being built.

74This name applied to the former water body by W. P. Blake is that of the Indians who inhabited the valley and of whom about 200 remain living on several small reservations near Mecca, Cabazon, and Palm Springs.

75The name Coachella is probably a misspelling of "conchilla" (Spanish for little shell), which was used in the early days and printed on the earliest maps.

76Macdougal, D. T., A decade of the Salton Sea: Geog. Rev., vol. 3, pp. 457-473, 1917.

|

|

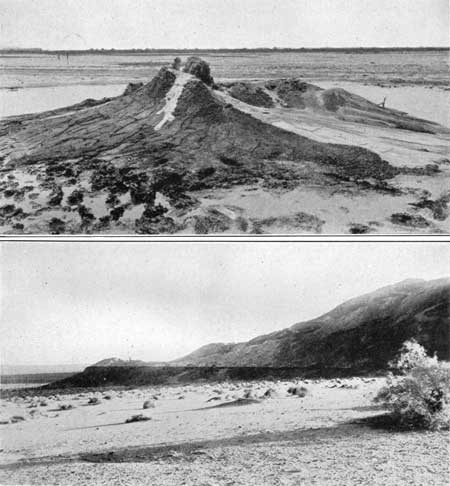

PLATE 38.—A (top), MUD VOLCANOES SOUTHWEST OF

NILAND, CALIF. Boiling mud probably heated by buried volcanic rocks. The

water is believed to rise on the San Andreas Fault. B (bottom), TRAVERTINE DEPOSIT MARKING STRAND OF ANCIENT LAKE CAHUILLA NEAR FIGTREE JOHN SPRING, ON SOUTH SIDE OF SALTON BASIN, CALIF. Santa Rosa Mountains at right. (Mendenhall.) |

Near the mouth of the Alamo River, on the southeast shore of the Salton Sea about 8 miles southwest of Niland, the presence of a center of volcanic activity is shown by ridges of lava pumice and active "volcanoes" of hot mud emitting sulphurous steam. One of these features is shown in Plate 38, A. There are other larger ones 75 miles farther south, near Volcano Lake, in Mexico. Pumice is obtained at Obsidian Butte,77 on the southeast shore of Salton Sea 11 miles northwest of Calipatria. It is interbedded with sediments and is the product of a volcanic eruption, probably from a cinder cone near the present mud volcanoes. The pumice is in pieces as large as 12 inches, and only those over 2 inches are shipped. The material is sorted by hand. There is another mine in a similar deposit 9 miles northwest of Calipatria, in an area of about 100 acres on a low rounded hill.

77Rock from ledges in this butte has been found to be a rhyolitic obsidian, metamorphosed to a banded mixture of tridymite and barbierite, probably by the action of hot volcanic gases. (A. F. Rogers.)

From Niland westward the mountains on the southwest side of the Colorado Desert or Salton Basin become conspicuous. To the southwest, across Imperial Valley, the Fish Creek and Superstition Mountains are clearly in view. Superstition Mountain consists of a ridge of gray biotite granite about 750 feet high, flanked on its north side by Tertiary sandstone and tuff with an interbedded flow of vesicular basalt about 200 feet thick. To the west are the rugged Santa Rosa Mountains, which consist of schists and granite; beyond this range rise the high San Jacinto Mountains, also made up of crystalline rocks. These ranges are sometimes known as the Peninsular Mountains because they continue far south down the great peninsula of Baja California. On the north side of the railroad west of Niland are low ridges of sandstone and shale of late Tertiary age which come to the surface at Niland. (Turn to sheet 27.)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/845/sec26a.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2007