|

Geological Survey

John Wesley Powell's Exploration of the Colorado River |

|

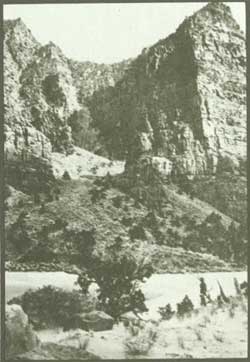

| Lodore Canyon, Green River, Colorado. |

Without trouble beyond the normal rigors of the voyage, the party continued downstream. After passing through Red Canyon, they camped under a giant cottonwood standing on the river bank. The party rested for 3 days before attempting the next canyon, which later they named Lodore.

Sitting high on a cliff over looking the camp, Powell wrote:

While I write, I am sitting on the same rock where I sat last spring, with Mrs. Powell, looking down into this canyon. When I came down at noon, the sun shone in splendor on its vermilion walls shaded into green and gray when the rocks are lichened over. The river fills the channel from wall to wall. The canyon opened like a beautiful portal to a region of glory. Now, as I write, the sun is going down and the shadows are setting in the canyon. The vermilion gleams and rosy hues, the green and gray tints are changing to sombre brown above, and black shadows below. Now 'tis a black portal to a region of gloom. And that is the gateway through which we enter our voyage of exploration tomorrow—and what shall we find?

On the morning of June 8 the travelers entered Lodore Canyon. Aboard the lead boat, the Emma Dean, Powell described how they proceeded:

June 8—I must explain the plan running these places. The light boat, "Emma Dean," with two good oarsmen and myself explore them, then with flag I signal the boats to advance, and guide them by signals around dangerous rocks.

When we come to rapids filled with boulders, I sometimes find it necessary to walk along the shore for examination. If 'tis thought possible to run, the light boat proceeds. If not, the others are flagged to come on to the head of the dangerous place, and we let down with lines, or make a portage.

|

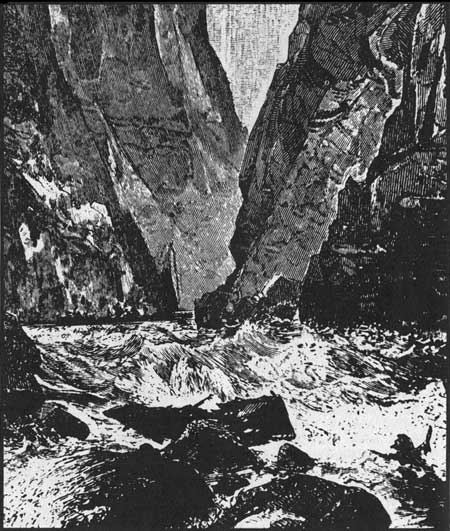

| Disaster Falls. |

And then disaster—

At the foot of one of these runs, early in the afternoon I found a place where it would be necessary to make a portage, and signalling the boats to come down, I walked along the bank to examine the ground for the portage, and left one of the men of my boat to signal the others to land at the right point. I soon saw one of the boats land all right, and felt no more care about them. But five minutes after I heard a shout, and looking around, I saw one of the boats coming over the falls. Capt. Howland, of the "No Name," had not seen the signal in time, and the swift current had carried him to the brink. I saw that his going over was inevitable, and turned to save the third boat. In two minutes more I saw that turn the point and head to shore, and so I went after the boat going over the falls. The first fall was not great, only two or three feet, and we had often run such, but below it continued to tumble down 20 to 30 feet more, in a channel filled with dangerous rocks that broke the waves into whirlpools and beat them into foam. I turned just to see the boat strike a rock and throw the men and cargo out. Still they clung to her sides and clambered in again and saved part of the oars, but she was full of water, and they could not manage her. Still down the river they went, two or three hundred yards to another rocky rapid just as bad, and the boat struck again amid ships, and was dashed to pieces. The men were thrown into the river and carried beyond my sight.

Although the three men were washed ashore uninjured, the No Name was completely wrecked. Rations, instruments, and clothing were lost. Only two barometers and a keg of whiskey were recovered. With good reason the men later named this place "Disaster Falls."

Of the recovered whiskey, Powell later wrote, ". . . they had taken it on board unknown to me, and I am glad they did, for they think it does them good—as they are drenched every day by the melted snow that runs down this river from the summit of the Rocky Mountains—and that is a positive good itself."

|

| Burning campsite. |

Bad luck continued to plague the explorers. Only a little more than a week later, they camped in a little alcove bordered by cedars on one side and a dense mass of box elders and dead willows on the other. Powell and Captain Howland went to explore the stream coming down into the alcove, and—

While I was away, a whirlwind came and scattered the fire among the dead willows and cedar spray, and soon there was a conflagration. The men rushed for boats, leaving all behind that they could not carry at first. Even then, they got their clothes burned and hair singed, and Bradley got his ears scorched. The cook filled his arms with the mess kit, and jumping onto the boat, stumbled and threw it overboard, and his load was lost. Our plates are gone, our spoons are gone, our knives and forks are gone; "Water ketch' em," "H-e-a-p ketch' em."

|

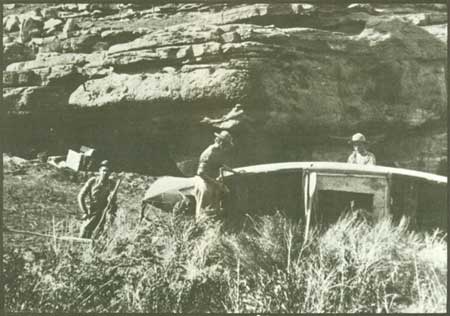

| Repairing a boat in the first Granite Gorge of the Grand Canyon. |

The men were compelled by the blaze to cut the boats loose, and the swift current quickly carried them down the river and over a rapids. All landed safely and made their way back to the camp where they found some clothing and bedding, also a few tin cups, basins, and a kettle. "This is all the mess kit we now have. Yet we do just as well as ever."

With great relief, on June 18, they emerged from the 21-mile-long Lodore Canyon.

. . . We are out of Lodore Canyon at last. Although its walls and cliffs, its peaks and crags, its amphitheaters and alcoves tell a story of beauty and grandeur, the roar of the waters was heard unceasingly from the hour we entered it until we landed here. No quiet in all that time.

| <<< Previous | <<< Cover >>> | Next >>> |

inf/powell/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006