|

Geological Survey

John Wesley Powell's Exploration of the Colorado River |

|

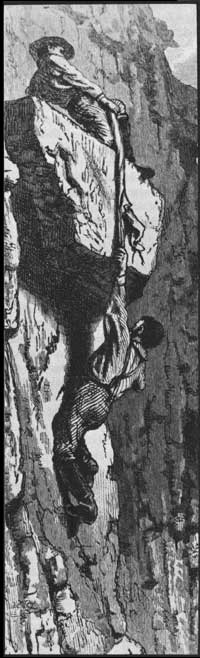

| The rescue. |

At the mouth of the Yampa River, they camped in a place they called Echo Park and soon ran into still another canyon.

. . . very narrow with high vertical walls. Here and there huge rocks jutted into the water from the walls, and the canyon made frequent and sharp curves. The waters of the Green are greatly increased since the Yampa came in, as that has more water than the Green above. All this volume of water, confined as it is in a narrow channel, is set edying and spinning by the projecting rocks and points, and curves into whirlpools, and the waters waltz their way through the canyon, making their own rippling, rushing, roaring music.

The boats were managed with difficulty, spinning as they did in eddies, and rearing and plunging with the waves. Before sunset, the party reached a quiet valley in which they camped, naming the place Island Park. After 2 days spent recalking the heavily leaking boats, they resumed their journey.

More rapids were run in Split Mountain Canyon, which they entered on June 25. The next forenoon was spent in portaging and then more gliding on gently flowing water, until on June 28, as George Bradley recorded in his diary, they—

. . . reached the desired point at last and have camped close to the mouth of the Uinta River. The White River comes in about a mile below on the other side. Now for letters from home and friends, for we shall here have an opportunity to send and receive those that have been forwarded through John Heard.

Several of the party went to the Uinta Indian Agency; Captain Howland observed that—

This valley, as also the valleys of the White and Uinta for twenty-five or thirty miles, has the appearance of being very fine for agricultural purposes and for grazing. The Indians on Uinta Agency have fine looking crops of corn, wheat and potatoes, which they put in this spring, on the sod. They have also garden vegetables of all kinds, and are cultivating the red currant. Everything is said to look well. Most of the Indians are now from the agency to see the railroad, while the rest stay to attend to their stock and keep their cattle from getting in and eating up their crops.

Here, Frank Goodman left the party, feeling he had had sufficient adventure.

They left the mouth of the Uinta on July 6 and trouble continued to plague them. On July 8, Powell almost lost his life. Through years of mountain climbing Powell had become used to heights. He could sit seemingly undisturbed on the edge of a 2,000-foot precipice. He often scrambled out of gorges to the rims of surrounding canyons, usually encumbered by bulky equipment. Most often he returned long after dark.

One day while he and Bradley were climbing a particularly precipitous cliff (Echo Rock), Powell reached a place where he could not go up or down, but could only cling to a crevice in the rocks with the fingers of his one hand. Powell later described his near disaster:

. . . by making a spring, I gain a foothold in a little crevice, and grasp an angle of the rock overhead. I find I can get up no farther, and cannot step back, for I dare not let go with my hand, and cannot reach foothold below without. I call to Bradley for help. He finds a way by which he can get to the top of the rock over my head, but cannot reach me. Then he looks around for some stick or limb of a tree, but finds none. Then he suggests that he had better help me with the barometer case; but I fear I cannot hold on to it. The moment is critical. Standing on my toes, my muscles begin to tremble. It is sixty or eighty feet to the foot of the precipice. If I lose my hold I shall fall to the bottom, and then perhaps roll over the bench, and tumble still farther down the cliff. At this instant it occurs to Bradley to take off his drawers, which he does, and swings them down to me. I hug close to the rock, let go with my hand, seize the dangling legs, and, with his assistance, I am enabled to to gain the top.

|

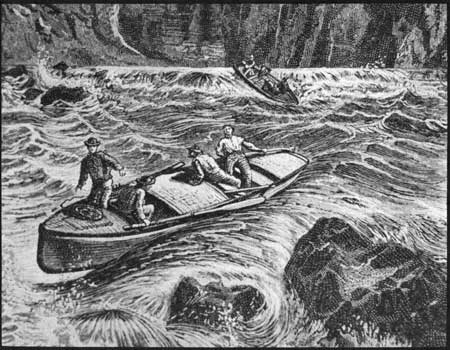

| Running a rapid. |

The two men continued their climb to the top of the cliff to make their scientific observations, and returned to camp apparently unmoved by the near disaster.

They were now into a "region of wildest desolation."

. . . The canyon is very tortuous, the river very rapid and many lateral canyons enter on either side. The walls are almost without vegetation; a few dwarf bushes are seen here and there clinging to the rocks, and cedars grow from the crevices—not like the cedars of a land refreshed with rains, great cones bedecked with spray, but ugly clumps, like war clubs beset with spines. We are minded to call this the Canyon of Desolation.

July 11—A short distance below last night's camp we run a rapid, and in doing so break an oar and then lose another, both belonging to the "Emma Dean." Now the pioneer boat has but two oars. We see nothing from which oars can be made, so we conclude to run on to some point where it seems possible to climb out to the forests on the plateau, and there we will procure suitable timber from which to make new ones.

We approach another rapid and standing on deck, I think it can be run and on we go. We try to land at the foot of the rapids but crippled as we are by the loss of two oars, the bow of the boat is turned downstream. We shoot by a big rock; a wave rolls over our little boat and fills her. I see that the place is dangerous and quickly signal to the other boats to land where they can. Another wave rolls our boat over and I am thrown some distance into the water. I soon find that swimming is very easy and I cannot sink. It is only necessary to ply strokes sufficient to keep my head out of water, though now and then, when a breaker rolls over me, I close my mouth and am carried through it. The boat is drifting ahead of me 20 or 30 feet and when the great waves have passed I overtake her and find Sumner and Dunn clinging to her.

As soon as the three men reached quiet waters, they turned the boat over to learn that their blanket rolls, two guns, and a barometer were lost.

| <<< Previous | <<< Cover >>> | Next >>> |

inf/powell/sec6.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006