|

Geological Survey Professional Paper 631

Analysis of a 24-Year Photographic Record of Nisqually Glacier, Mount Rainier National Park, Washington |

CONCLUSIONS

The information and data on glacier characteristics and changes contained in this report are believed typical of what can be derived from a long-term record of annual photographs. A summary of the findings follows:

1. Data on changes in ice margins are readily obtainable from photographs. Likewise, changes in glacier thickness can be derived either from the positions of the ice margins along a canyon wall or from measurements made on the photographs of distances from a bedrock feature down to a bulge in the ice surface, with the latter photographed as a profile or "silhouette" from below. Both methods check well with the results of stadia surveys; values from the second method probably are accurate in this area to within plus or minus 25 feet (8 m).

2. Annual values of the surface slope at profile 2 were measured on photographs and are believed to be at least as accurate as those determined from the contour maps. Absolute values of the slope ranged from 5 to 10 degrees. A photographic analysis of slope can be made rather accurately from annual pictures provided there is established by field surveys the projection of a reference vertical line on the canyon wall directly opposite the picture station, identifiable on each print with respect to enduring landmarks. Also, the photographic station used must not be much higher than the glacier surface.

3. Position of the summer snow line on Nisqually Glacier was found to range between altitudes of about 5,800 and 7,300 feet (1,750 and 2,250 m), whereas the firn edges appeared to be between altitudes of about 6,000 and 7,300 feet (1,850 and 2,250 m). However, the snow lines and firn edges on this glacier usually are very irregular. Aerial photographs or a more complete coverage of ground photographs than is available for this project would be needed for an analysis of the snow and firn limits in relation to climatic fluctuations.

4. Photographs are helpful in analyzing the rates of retreat and advance of a glacier's terminus and in distinguishing an advancing terminus from a retreating one, through illustration of the characteristic appearance of each. If advancing, the front of the terminus is steep, bulging, and crevassed; if receding or stagnant, it usually has a noncrevassed, more gently sloping appearance or it may become hummocky or segmented.

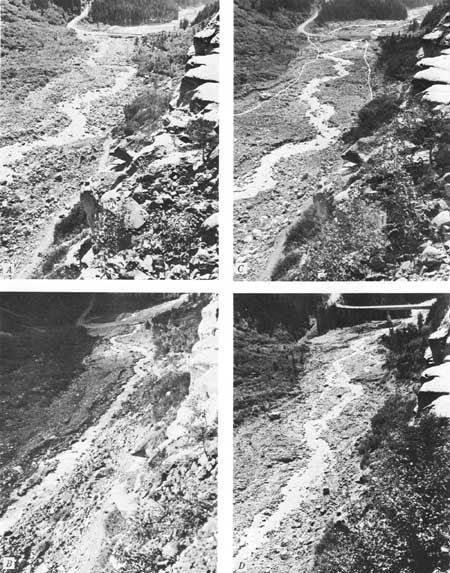

5. The pictures portray the appearance of a wasting glacier, including its stagnant lower reaches, during the latter part of a long period of recession. Later, they illustrate waves of fresh ice advance which engulfed the nunatak and replaced the segmented, stagnant terminus by a bulging, crevassed "fat" looking front.

6. Photographs illustrate the occurrence, nature, and changes in moraines and debris-covered ice ridges. They also show the sources, distribution, and general nature of the debris carried on a glacier's surface.

7. The dynamic condition of a glacier is indicated quite well by the nature and pattern of the crevassing as well as by the general character of the glacier surface. During ice advances, the crevasses are larger and coarser in pattern than during a recession. A hummocky surface reflects the wasting and ablating condition of stationary or receding ice, as is shown on the photographs.

8. Information about the progress of erosion on the banks and lateral moraines of a glacier can be determined from annual photographs. Canyon wall bedrock features change more rapidly than might be supposed.

9. Some of the effects of glacier outburst floods, often more damaging than is realized, are illustrated by the photographs in this report. The removal or killing of many large trees and the deposition of enormous boulders are shown.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pp/631/conclusions.htm

Last Updated: 01-Mar-2006