|

Geological Survey Professional Paper 631

Analysis of a 24-Year Photographic Record of Nisqually Glacier, Mount Rainier National Park, Washington |

QUALITATIVE INTERPRETATIONS

(continued)

MORAINES

Photographs may bring out some detailed moraine and erosion patterns not noticed by an observer on the ground because film can emphasize color values and relief otherwise not very apparent. The pictures for different years can readily be examined and compared with respect to subtle features, which may easily be forgotten if observed only during occasional field inspections. An example of such a feature is the light-colored band in the large medial moraine near the east side of the glacier in figure 4. Another example is shown in the 1940 photograph taken from station 12 (fig. 26), which illustrates several small lateral moraines that had been deposited along the east side of the glacier at an altitude of 6,400 feet (1,950 in), suggesting a discontinuous rate of recession of the glacier.

CREVASSING AND GENERAL CHARACTER OF THE GLACIER SURFACE

In addition to the data presented in the preceding sections, some further examples of what photographs can show about glaciers are given below on the following subjects (all of which have not been studied herein in detail):

1. Crevassing patterns, from which the nature of the subsurface structure, the direction of ice movement, and changes in rates of movement can be interpreted.

2. Information of changes in surface slope, or the shape of its longitudinal profile, in areas not covered by surveys and contour maps.

3. Some details about advance, recession, debris load, contour, movement, thickness, and surface erosion.

Terminus to profile 1

Photographic series 1—NE (figs. 16-19) and 5 (figs. 20-25) illustrate the gradual deterioration and shrinkage of the entire glacier downstream from the nunatak and profile 1, and its subsequent reactivation. This lower area was virtually stagnant from about 1944 to 1954, but a spectacular advance of fresh ice passed the nunatak in 1954-55 and reached the terminus in 1963. By 1965 it had given form to a new, vigorous-looking terminus.

Profile 1 to about 1,000 feet (300 m) above profile 2

Captions for the photographs in series 6 (figs. 27-31), 7 (figs. 2-5), and 14—W (figs. 7-10) contain miscellaneous descriptive comments for this reach of the glacier. Certain features can be seen more clearly in one series than in the others. The following comments about the photographs in series 6 and 7, arranged in chronological order for each series, include most of the descriptive material that is contained in the captions:

Photographic series 7 (figs. 2-5)

| 1890 | The glacier above the nunatak is at the highest stage ever known to have been photographed. |

| 1915 | Note the debris-covered moraines along far side of glacier, which were not visible in 1890. The nunatak (at lower right) still is covered by ice. |

| 1945 | Nunatak is exposed. Slope at profile 2 is almost flat. Light-colored band of debris shows in medial moraine at right center; Wilson Glacier ice discharge is very low. There is almost no crevassing in middle reach. |

| 1963 | Crevassing in midglacier near profile 2 is extremely coarse or rough. Ice level at profile 2 is the highest in nearly 30 years. Direction of the crevassing pattern in east part of glacier above the nunatak, when compared with that in figure 27, indicates that as the nunatak becomes submerged a lesser proportion of the east half discharge is diverted toward the west canyon wall. |

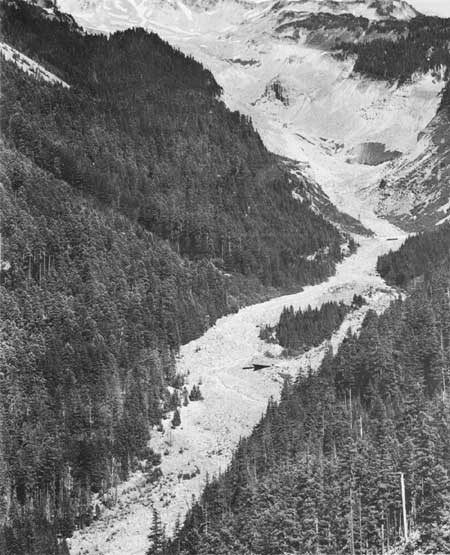

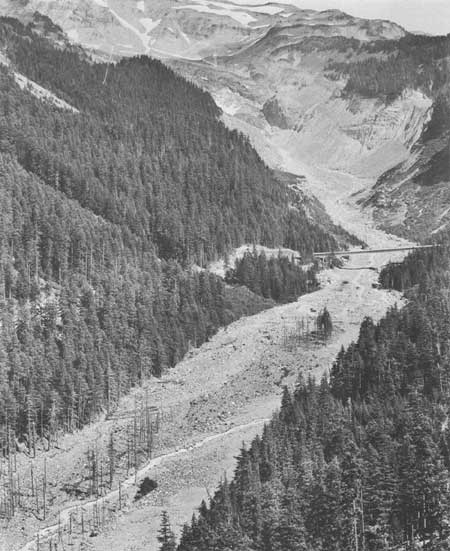

Photographic series 6 (figs. 27-31)

| 1952 | White-ice stream at left has much more uniform slope than in 1945. This is first year since the early 1940's when fresh crevasses have appeared in midglacier above the nunatak. Their direction, at a steep angle to the general direction of ice flow, indicates strong longitudinal shearing above the nunatak caused by more vigorous flow in the east half of the glacier. |

| 1954 | New ice front is passing the nunatak. Note severity of the crevassing upstream and its continued angling (since 1952) with respect to the valley axis. |

| 1958 | Ice level at profile 2 peaked in 1957; at profile 1 it remained constant for 4 years before again advancing in 1962. The slope at profile 1 appears rather steep. In this photograph there is a good portrayal of the ablation of crevasse walls. |

| 1961 | See large patch of debris at lower left which has greatly increased since 1958. A flat reach appears to be forming in white-ice slope above profile 2. Nunatak is being topped with ice. |

| 1965 | Profile 2 appears to be on a long reach of rather uniform slope, with flat slope occurring not far upstream from there. Nunatak is almost entirely engulfed with thick ice. This year the ice level at profile 1 is highest since about 1938. |

1,000 feet (300 m) above profile 2 to above profile 3

For comments about this area, see captions of the photographs in series 15 (fig. 12) and 13 (figs. 32-34). Series 15 provides some coverage of upper part of glacier for the period prior to 1949, before series 13 was begun. A summary of the comments contained in the captions follows:

Series 15 (fig. 12)

| 1944 | Glacier is nearing the end of a long period of recession, and at this stage there is very little crevassing. The inflow of ice from Wilson Glacier is low; note the large exposures of bedrock. A heavy load of debris is being carried, contributed from both banks of Nisqually Glacier. |

Series 13 (figs. 32-34)

| 1949 | This picture was taken from a point about 500 feet (150 m) upstream from the station where remainder of the series was taken. Crevassing pattern has expanded since 1944, especially in areas nearest the camera station. Bedrock outcrops at lower end of Wilson Glacier are nearly covered. |

| 1957 | Glacier surface at profile 3 is 10 ft (3 m) higher than in 1953; ice field at top of cliff at left is much thicker. Crevassing now extends to east edge of the glacier. |

| 1965 | Surface of glacier in general appears a little smoother and slopes less steep. Firn can be seen in several areas. Ice on cliff at left appears about the same as in 1962. |

EROSION AND DEPOSITION

Banks and lateral moraines

Annual photographs reveal the progress of erosion along the banks of a valley glacier and along old lateral moraines. The 1947 and 1965 views in series 11 (fig. 35) illustrate 18 years of erosion of west side of the old east-bank lateral moraine. Along this part of the moraine the average lateral recession of its crest over the 18-year period has amounted to a total of 10-15 feet (3-5 m).

In regard to erosion of the banks of a glacier, the views in series 14—W (figs. 7-10) show how some of the bedrock areas on the steep hillside above the west end of profile 2 became unrecognizable within 20 years. Note changes in the lower rock formations seen in the 1942 and 1960 views, which were photographed under similar light conditions. Thus, on photographs of a canyon wall, it may be difficult to pick out bedrock features that will be usable as long-term landmarks for measurements in photographic studies. In the present study, a few usable points were found that could be identified on pictures throughout the 24-page period of record.

Outburst floods

Repetitive photographs also portray changes in topography and vegetation in the channel and valley below a glacier that result from outburst-type floods (jokulhlaups). Three such floods emanating from Nisqually Glacier are described briefly below.

Flood of October 14, 1932. This flood tore away the reinforced concrete arch bridge which had been constructed in 1926. A precipitation total of 6.90 inches (175' mm) fell at Paradise Ranger Station October 10-13, inclusive. It is interesting to note what apparently is the deck of that bridge clearly visible in the 1947 view (fig. 37) in series 3 (figs. 36-38), just below the tree-covered island near the center of the picture.

Flood of October 24-25, 1934. A series of outburst surges from the glacier, according to the monthly report of the Superintendent, Mount Rainier National Park, dated November 5, 1934, "completely plugged the bridge and piled rock and debris 15 feet deep on top of the arch. Approach roads on both sides of the bridge were washed out." Precipitation of 8.92 inches (227 mm) occurred at Paradise Ranger Station October 20-25, inclusive. This bridge, less than 2 years old and situated at the same site as the bridge it replaced after the 1932 flood, was reconditioned and used until its wash out in 1955.

Flood of October 25, 1955. The flood occurred about noon and destroyed bridges and other property downstream. It was preceded by heavy rainfall (a total of 5.51 inches (140 mm) was measured on the 24th and 25th at Paradise Ranger Station) and was observed by a Park Ranger to flow in several large surges. The frontal wave of the first surge was estimated to be 20 feet (6 m) high, and the water carried many large rocks and chunks of ice that were visible at the surface. The first surge tore from its abutments the heavily reinforced 80-foot (24-in) span, concrete highway bridge.

Natural changes below glacier from floods and other causes

The 1934,4 1947, and 1965 pictures in series 3 (figs. 36-38) illustrate the removal of vegetation, channel widening, and subsequent killing of trees that occurred for a few thousand feet (500-1,000 m) below the bridge as a result of glacier floods of the early 1930's and 1955.

The flood channel in the vicinity of the highway bridge was widened by the 1955 flood, and some vegetation was removed, as illustrated by the 1949 and 1956 views in series 2-5 (figs. 39A, C). Margins of the flood plain and vegetation as they existed a month before the flood are indicated by white lines in figure 39C (1956). Note also the automobile-size boulders that were cast up onto the parking area just to left of and above the bridge, and the much larger boulder deposited upstream. Many large trees downstream from the bridge were washed away.

The annual photographs in series 2—S (only a few of which are shown in this report) show some interesting variations in the configuration of the low-flow channel between the glacier terminus and the highway bridge. They reveal how within one season the channel would change from meandering to straight, or vice versa, then retain one form for several consecutive years. An example is evident from a comparison of the photographs shown as figures 39A and 39B, for 1949 and 1950. Note also the new terraces visible in 1950 along the flood plain. Each subsequent annual view showed that the channel remained straight from 1950 until after 1953 (which was the last view taken until 1956).

A tributary alluvial fan, first visible in 1960, was deposited on right-bank flood plain above the bridge; by 1965 (fig. 39D) it had become a little larger.

The 1932-36 photographs taken by the National Park Service looking upstream from the bridge, which are not published here, indicate that the flood of October 1934 was very substantial and erosive above the bridge as well as in the vicinity of the island 1,000 feet (300 m) downstream.

4This "1934" undated photograph closely matches the appearance of the glacier terminus in a National Park Service photograph dated September 5, 1934. The match is fair, but less perfect, with their 1933 photograph; it is clearly poor with their October 1, 1932 photograph. Thus it seems likely that this "1934" picture, upon which the large amount of downstream flood plain vegetation is visible, was taken after the 1932 glacier outburst flood and before the October 1934 flood, when denudation of that vegetation probably took place.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pp/631/sec4b.htm

Last Updated: 01-Mar-2006