|

Geological Survey Professional Paper 669

The Colorado River Region and John Wesley Powell |

RECENT STUDIES (SINCE 1935) AND THEIR INTERPRETATION

The greatly increased number of geological investigations and the accelerated pace at which new data on Grand Canyon stratified rocks have become available since 1935 are impressive. One trend has been toward specialization as new techniques in field and laboratory work have been developed and as new information has become available from related fields or from surrounding regions. A second trend has been toward broad regional generalizations made possible by the large amount of comparative data accumulated and compiled and by the application of statistical methods of study.

In order to summarize the results of recent studies in the Grand Canyon area, each of the specific phases of geology involved is considered below. Within this framework, the principal contributions, including interpretations, are presented in chronological sequence, from oldest to youngest formation.

Rock Classification—Revisions And Additions

Few major changes in the nomenclature of the Grand Canyon stratigraphic column have been proposed since Noble's definitive work of 1922. Principal additions to the list of formations and groups are the Nankoweap Group of Van Gundy (1934), Pakoon Limestone and Queantoweap Sandstone of McNair (1951), Callville Limestone, and Toroweap Formation. The name Rama Formation was suggested (Maxson, 1961) for intrusive rocks of late Precambrian age in the Bright Angel quadrangle, but because farther east these igneous rocks include basaltic flows that are interbedded with strata of the Dox Sandstone, the desirability of applying this name is questionable.

Nankoweap Group is the term applied by C. E. Van Gundy (1934; 1951) to sandstones and shales formerly assigned by Walcott to the lower part of the Chuar Group and the upper part of the Unkar Group of late Precambrian age. It is described as having erosional unconformities both above and below and as having a thickness of about 300 feet.

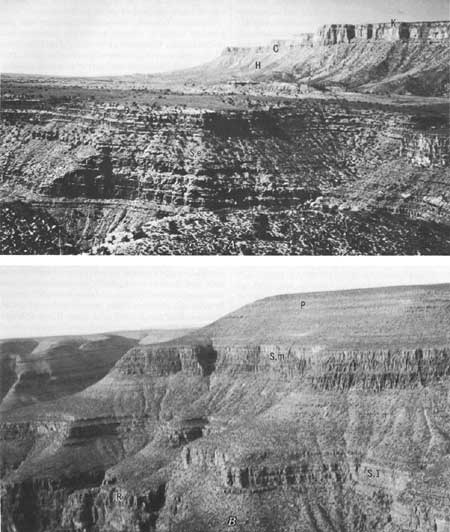

The Callville Limestone (Longwell, 1921, p. 47; 1928) and the Pakoon Limestone (McNair, 1951, p. 524-525) (fig. 10B, this publication) are names originally given to rock units outside the Colorado Plateau but subsequently recognized in the walls at the west end of Grand Canyon. Both units are dominantly limestones that are laterally equivalent to parts of the Supai Formation in the eastern Grand Canyon area. Where the boundary between the Supai Formation and its carbonate equivalents should be drawn still is not known; clarification of this problem awaits further detailed work.

|

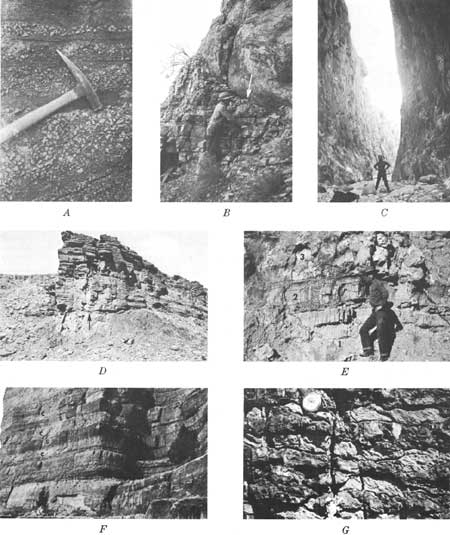

| FIGURE 10.—Stratified rocks of Grand Canyon. A, View west from Twin Springs Canyon; (S,e) Supai Formation, Esplanade cliff unit; (H) Hermit Shale; (C) Coconino Sandstone; (T) Toroweap Formation; (K) Kaibab Limestone. B, View north from head of Pigeon Wash: (R) Redwall Limestone; (S,1) Supai Formation, lower cliff unit; (S,m) Supai Formation, middle cliff unit; (P) Pakoon Limestone of Mcnair (1951). |

The Queantoweap Sandstone was described by A. H. McNair (1951, p. 525-526). It is the upper cliff member of the Supai Formation in western Grand Canyon and has long been known as the Esplanade Cliff unit. Throughout most of the canyon area, this unit is considered the upper part of the Supai Formation.

The name Toroweap Formation (fig. 10A) was proposed by McKee in 1938 (p. 12-28) for lower members of the Kaibab Limestone of Darton (1910); the name Kaibab was restricted to the original upper units. This revision serves to emphasize dual transgression as represented by the limestone members of each formation and, in addition, gives recognition to the unconformity between these units and to differences in faunas of the two limestones.

Most of the recent revisions and additions to the classification and nomenclature of stratified rocks in Grand Canyon have involved units of member status. In the Cambrian, Mississippian, Pennsylvanian, and Permian rocks, such subdivisions have been recognized, and names have been applied to most of them.

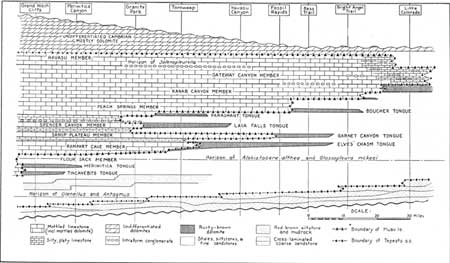

In the Cambrian strata of Grand Canyon, key beds or marker beds of various types have been traced for many miles along canyon walls; these beds make feasible the recognition of intervening stratigraphic units, most of which have been given formal names (McKee and Resser, 1945, p. 80-110). These units consist of eight members and seven tongues, as illustrated in figures 11 and 12 of this report. Members are recognized within the carbonate rock sequence by virtue of certain marker beds, considered to be essentially time planes, that form bounding surfaces. Tongues of dolomite extend laterally from the limestone members into a sequence of shales, siltstones, and fine-grained sandstones. Thus, although the formation boundaries cross time planes because of transgressions and regressions, the members within these Cambrian strata do not.

|

| FIGURE 12.—Correlation of Cambrian formations and members in the Grand Canyon. From McKee and Resser (1945, fig. 2B). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

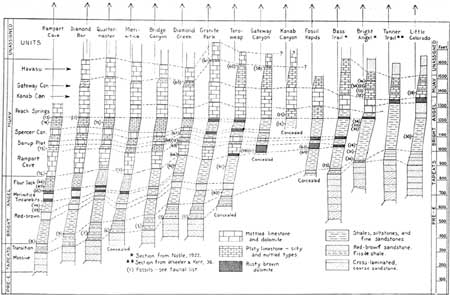

The Redwall Limestone has been divided into four members, first tentatively designated by numbers and then by letters, as indicated in figure 13. The members were later given the formal names, in ascending order, of Whitmore Wash, Thunder Springs, Mooney Falls (fig. 14C), and Horseshoe Mesa (McKee and Gutschick, 1969, chap. 2). These well-defined units are based on distinctive lithologic features and are believed to represent two periods of marine transgression, each followed by a period of regression. They apparently are independent of time units as shown by faunal zones, especially those of foraminifers, that are abundant in these rocks.

|

| FIGURE 13.—Development of stratigraphic subdivision of the Redwall Limestone. From McKee and Gutschick (1969, table 1). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| FIGURE 14.—Some sedimentary features in stratified rocks of Grand Canyon. A, Conglomerate containing chert and jasper pebbles; forms key bed in lower part of Supai Formation, Whitmore Wash. B, Channel at top of thin-bedded carbonate rock of Cambrian age filled with poorly-bedded Devonian dolomite, Lone Tree Canyon. C, Massive limestone cliff formed by Mooney Falls Member of Redwall Limestone, Parashant Canyon. D, Cambrian-late Precambrian unconformity. Tapeats Sandstone resting on beveled surface of diabase in Dox Sandstone, Cremation Canyon. E, Cyclothem of (1) red bed, (2) aphanitic limestone, and (3) bedded gypsum (ascending order) in Toroweap Formation, Wolf Hole. F, Beds of c(C) earthy chert, alternating with beds of c(s) calcareous sandstone, Kaibab Limestone, near south Kaibab trail. G, Bedded chert (dark bands) alternating with aphanitic limestone (light bands) in Thunder Springs Member of Redwall Limestone, Iceberg Canyon. |

Subdivision of the Supai-Hermit red-bed sequence is necessary if progress is to be made in unravelling the history of these rocks; however, difficulties are posed by the lack of extensive fossil zones that can be used as markers and by the similarity of different rock units. Fortunately, because datable limestones and dolomites intertongue with the red beds on the west and south, the dating of major rock units in some areas has been accomplished. Furthermore, several thin conglomerate units (Fig. 14A,) have been shown to be widespread and probably mark hiatuses between natural divisions within the rock sequence. In any event, faunal evidence from the limestones shows that the Pennsylvanian System is represented by rock equivalents of the Morrow, Des Moines, and Virgil Series and that a series equivalent (Atoka, Missouri) is missing between each two of these. Furthermore, rocks of Wolfcamp age of the Permian rest unconformably on rocks of Virgil age. Thus, although no formal names are as yet proposed and boundaries are not recognized in many areas, available evidence suggests that at least four definite subdivisions (members) occur with in the Supai-Hermit sequence.

Classification of the Kaibab Limestone (fig. 15) has been changed several times during the past half century. Three members (A, B, C) were recognized by Noble in 1922 (p. 68-70), but in a later, more detailed study, he (Noble, 1928, p. 52-54) included five members (A—E) in which the designations of individual units did not correspond with the earlier ones. When still another change in assignment became necessary because of the designation of the Toroweap Formation (McKee, 1938, p. 18) (fig. 16, this report), the Greek letters α, β, and γ were used (descending order) for the members of each formation to avoid confusion with either of the earlier systems. The γ member is believed to represent the time of advancing seas, the β member the time of extended seas, and the α member the time of receding seas.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FIGURE 15.—Classification of rock units in the Kaibab Formation. From McKee (1938, table 4). |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FIGURE 16.—Classification of rock units in the Toroweap Formation. From McKee (1938, table 2). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pp/669/secb6.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jun-2006