|

Geological Survey Professional Paper 669

The Colorado River Region and John Wesley Powell |

RECENT STUDIES (SINCE 1935) AND THEIR INTERPRETATION

(continued)

Refinements In Age Determination

Since 1886, rocks of the Grand Canyon Series have been considered Precambrian in age (Walcott, 1886, p. 41), and in 1890, they were referred to the "Algonkian" on the basis of stratigraphic position (Walcott, 1890, p. 50, 52). No fossils of diagnostic age have yet been found in these rocks, and no direct dating by potassium-argon, rubidium-strontium, or lead-uranium measurements has yet been reported, but new data have strengthened the stratigraphic evidence. Discovery that the Tapeats Sandstone is of Early Cambrian age, at least in western Grand Canyon, and that it is a continuous transgressive sand body across the region from west to east (McKee and Resser, 1945, p. 11-15) shows that the Grand Canyon Series is clearly older than earliest Cambrian. Unconformably underlying the series, moreover, are metamorphic rocks intruded by pegmatites that have a minimum age of 1,540 m.y. on the basis of rubidium-strontium measurements (Giletti and Damon, 1961). These measurements indicate that rocks immediately below the Grand Canyon Series either are to be correlated with the Mazatzal revolution (Damon and Giletti, 1961) or are younger, as argued by Wasserburg and Lanphere (1965, p. 755). In either case, the Grand Canyon Series must be considerably younger than the dated pegmatites.

Correlation between the Grand Canyon Series and certain other rocks long suspected to be of similar age—especially the Apache Group of southern Arizona and the Belt Supergroup of Montana and Idaho—involves many uncertainties. Nevertheless, recent studies of the Apache Group by Shride (1967, p. 80-81) have prompted him to suggest, on the basis of similar sequences of distinctive features, a correlation between parts of this group and lower units of the Unkar. He believes that stratigraphic equivalents of the Dox Sandstone and the Chuar Group are absent in southern Arizona because of erosion prior to Cambrian deposition. Further progress in the matter of correlation probably must await the determination of absolute ages.

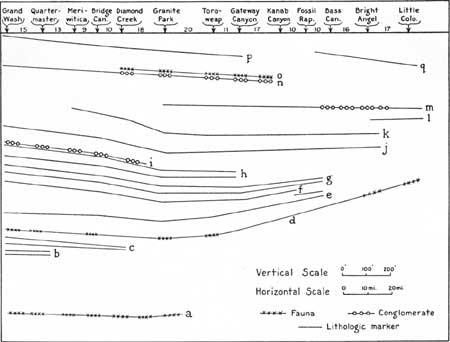

Today, the age of the Cambrian rocks of Grand Canyon seems to be well established, on the basis of extensive fossil collections. These collections consist mostly of trilobites and brachiopods and include some gastropods, Conchostraca, cystids, and sponges, described for the most part by C. E. Resser (in McKee and Resser, 1945, p. 185-220). Systematic collecting of these fossils has demonstrated that they occur in well-defined zones ranging from late Early Cambrian to approximately the middle of Middle Cambrian time (McKee and Resser, 1945, p. 29-33). Although many of the fossil genera have considerable vertical range, extending through much of the Cambrian of the area studied, the species are mostly very limited in range, being restricted to single members or rock units 150 feet thick or less. Three principal faunal zones in the Grand Canyon occur within a rock thickness of slightly more than 1,000 feet, and because of the widespread distribution and abundance of some species, these fossils form excellent horizon markers, as shown in figure 17.

Little more is known today, concerning the age of Grand Canyon rocks assigned to the Devonian System, than was known in 1879 when Walcott (1880, p. 225) discovered "placoganoid fishes" in the walls of Kanab Canyon, a few miles above its junction with the main canyon. Additional fish specimens were found by Noble (1922, p. 51, 52) at Sapphire Canyon, and these were assigned to the genus Bothriolepis by Gidley; none, however, have been reported since. The early specimens from Grand Canyon are discussed in a restudy of Devonian fresh-water fishes from the Western United States by Denison (1951, p. 221, 230) who concurs in the generic identification and states that the genus is "a characteristic element of Late Devonian fresh-water faunas throughout much of the world" (1951, p. 223). In the most recent stratigraphic report on the Devonian of Arizona (McKee, in Poole and others, 1967, p. 887), the Temple Butte Limestone of Grand Canyon is shown as probably representing much of the Frasnian stage or lower part of the Upper Devonian Series. A suggestion is made that the Temple Butte is approximately correlative with the fossiliferous and well-dated Jerome Member of the Martin Formation in central Arizona, the fossils of which have been reported on by Teichert (1965).

In the Redwall Limestone, determination of fossil zones and consequent age assignments for various parts of the formation have resulted from extensive systematic fossil collecting within recent years (McKee and Gutschick, 1969, chap. 4). Foraminifers, brachiopods, and certain genera of corals occur in distinct zones; most other faunal groups seem to owe their distribution patterns to facies control. The foraminifers form six zones, two of which are divided into two subzones each, and this zonation represents an almost continuous faunal succession through the formation (Betty Skipp, in McKee and Gutschick, 1969, chap. 5). Among the corals, many forms are long-ranging, so they are not useful in zonation; but two species, Dorlodotia inconstans and Michelinia expansa form very distinctive widespread zones (W. J. Sando, in McKee and Gutschick, 1969, chap. 6). Brachiopods likewise seem to be useful as zone indicators, but details of their distribution and significance have not yet been published.

In the Redwall Limestone, rather good agreement has been attained in age determinations based on independent studies of the main faunal groups (McKee and Gutschick, 1969). Zones of foraminifers show an age range from late Kinderhook to middle? Meramec. Brachiopods from several localities confirm the Kinderhook age in the basal parts of the sections involved; brachiopods range upward through Osage and into Meramec forms in many sections. Corals likewise indicate a Meramec age for the uppermost beds in many places. In one locality (Bright Angel trail), a thin remnant of strata of Chester age, dated both by brachiopods and by foraminifers, has been preserved. In general, age determinations and the character of the faunas upon which these are based indicate a close relationship between the Redwall and other Mississippian Rocky Mountain formations such as the Madison, Leadville, Escabrosa, and Lake Valley Limestones.

The age assignment of the Supai-Hermit red-bed sequence, which has for a long time fluctuated between Pennsylvanian and Permian, seems finally to be stabilizing, as more and more diagnostic fossils are uncovered in various parts of the area and at different horizons. The age of the Hermit Shale was determined as "upper Lower Permian" by David White (1929, p. 38) on the basis of plant species in its relatively large flora. The Pakoon Limestone—a carbonate tongue extending into the upper part of the Supai Formation from the west—has been shown by McNair (1951, p. 525) to be Permian also, for it contains an abundance of diagnostic Wolfcamp fusulinids. More recently, numerous collections of invertebrate fossils, mostly brachiopods and fusulinids, have been made by the writer (unpub. data) from limestone tongues lower in the Supai, showing that Pennsylvanian rocks of Virgil, Des Moines, and Morrow age are also represented in the Supai.

Both the Coconino Sandstone and the Toroweap Formation, between the Hermit Shale and Kaibab Limestone, have long been assigned to the Permian System because of stratigraphic position. Virtually the only fossils that have been found in the Coconino are tracks considered reptilian, and although these are scarcely reliable for precise correlation on the basis of present knowledge, it is significant that some of the same forms occur also in the Lyons Sandstone of Permian age in Colorado (Gilmore, 1926, p. 5, 13). The fauna of the Toroweap is relatively small and nondiagnostic, but in general it is similar to that of the Kaibab, which has been correlated with the standard Permian of Texas. Thus, the Leonard age of the Toroweap seems well established.

The Kaibab Limestone that forms the rim of Grand Canyon and constitutes the youngest Paleozoic formation in northern Arizona is now believed almost certainly to be of late Leonard age (McKee and Breed, 1969). Correlation with the standard Permian sequence of Texas has been established on the basis of brachiopods (McKee, 1938, p. 170), mollusks (Chronic, 1952, p. 111), siliceous sponges (Finks, 1960, p. 36), and nantiloids (Miller and Youngquist, 1949, p. 9). Although these faunal groups do not all suggest correlation with the same rock unit in Texas, the youngest probable correlative in the Texas sequence is the Road Canyon Formation, formerly the "First Limestone member" of the Word Formation, which has been shown by Cooper and Grant (1966, p. E6) to belong to the Leonard Series.

Fossils of the Kaibab Limestone, especially the brachiopods, make possible rather firm correlations between it and Permian strata of surrounding areas. The typical brachiopod assemblage of the Kaibab occurs in the Concha Limestone of southern Arizona (Gilluly and others, 1954, p. 31; Bryant and McClymonds, 1961, p. 1329). This assemblage also is found in the section in the Confusion Range, western Utah, so the name Kaibab has been extended to that area (Hose and Repenning, 1959, p. 2178-2179). Farther east in Utah, all marine Permian strata seem to be of Guadalupe age and therefore are younger than the Kaibab (McKee, 1954, p. 21; Yochelson, 1968, p. 625).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pp/669/secb6a.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jun-2006