|

Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Bulletin 86

Geology of the Shenandoah National Park, Virginia |

INTRODUCTION

GEOLOGY OF THE SHENANDOAH NATIONAL PARK, VIRGINIA

Thomas M. Gathright II

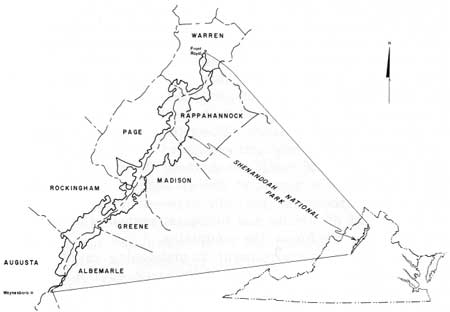

Shenandoah National Park lies astride a 70-mile segment of the Blue Ridge mountains in north-central Virginia between Front Royal at the park's north entrance and Rockfish Gap near Waynesboro at the south entrance. The park occupies more than 300 square miles in portions of eight counties (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Location map of Shenandoah National Park, Virginia and surrounding counties. |

The main body is 3- to 6-miles (5- to 10-km) wide with a very irregular boundary that encloses small portions of the Shenandoah Valley to the west and many of the lower Blue Ridge foothills to the east. Skyline Drive, the north-south highway along the crest through the park; the Appalachian Trail; and the numerous park-maintained footpaths provide access to the mountain wilderness and many scenic vistas of the Blue Ridge, the Shenandoah Valley, the Massanutten mountain range west of the park, and the rolling Piedmont to the east. The Blue Ridge within the park area reaches 4,050 feet (1,234 m) in elevation on Hawksbill and consists of high, broad mountains, interconnected by high gaps and saddles with many peaks, and sinuous, sharp-crested ridges. Two of the more prominent gaps, Thornton and Swift Run, lend access to the central portion of the park via U. S. Highways 211 and 33, respectively, and divide the park into three sections—northern, central, and southern.

The quiet but rugged grandeur of the wilderness, the high meadows and rocky slopes, the arcuate escarpments, and plunging cataracts in the park area all compound a feeling of permanence that belies the action of ongoing geologic processes. Yet, it is these processes that through the past billion years, or more, have formed and shaped these mountains and the rocks from which they were carved. Much of the history of these processes and of the resultant mountains can be found in the Blue Ridge rocks. Some geologic processes and events can be documented with certainty, others are more obscure, and many we can only speculate about. Even those processes going on today such as weathering and erosion of the mountain surface are complex and not easily understood. What we see in the Blue Ridge today is a part of the geologic framework of the earth's crust altered and partially exposed by geologic events and the impact of climate and biological processes on the rock material that now forms the mountains.

Today, the park environment is undergoing rapid change. Indians were the first to leave their mark on the mountain forests, girdling the trees and burning the undergrowth to make small clearings for gardens or for hunting purposes. These changes were probably insignificant, as the small Indian population had only rudimentary hand tools and fire for clearing the forest. Early colonial settlers cleared more land and cut timber for their own use, but they had little more impact on the mountain wilderness than the Indians. Large tracts of virgin timber were still present in the park area in the late nineteenth century when rail access to the foot of the Blue Ridge and demand for construction materials in the northeastern United States brought the sawmills to the mountains. The timbering operations that followed and the devastating chestnut blight in the early twentieth century removed or killed many of the commercially valuable trees leaving only a few virgin stands, all devoid of the chestnut, in the less accessible areas.

In the nineteenth century the discovery of small deposits of iron, manganese, and copper brought mining and prospecting to the mountains and western foothills of the park. Iron and manganese deposits along the west foot of the Blue Ridge, generally just west of the park boundary, have been mined for more than 100 years. Iron was mined only until the early twentieth century, but manganese was mined intermittently until about 1960 with peak mining periods occurring around 1890 and during the two World Wars. Exploration trenches, opencut mines, and shafts mark the location of more than 40 abandoned mines in or just west of the park. Remnants of the largest and most productive opencut manganese mine can be seen from Crimora Lake Overlook on Skyline Drive. Copper mining was also attempted at several locations in or near the park during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Small amounts of copper oxides and sulphides and native copper occur in the ancient basalts that form much of the Blue Ridge crest. Only small mine operations were developed because the copper ore was neither extensive nor of high quality. Abandoned mines and spoil may be seen on Stony Man and near Dark Hollow Falls (Plate 2). However, the copper mining operations had few effects on the wilderness and these are rapidly fading away with the return of the forest.

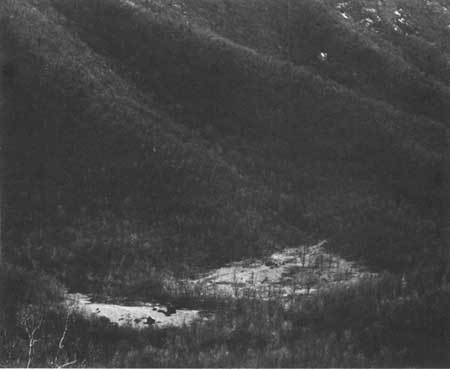

During the establishment of Shenandoah National Park in the nineteen-twenties and -thirties at least several hundred families still lived in the park area, subsisting on small mountain farms and tending cattle or orchards on partially cleared mountain slopes or hollows (Figure 2). Small second-growth timber covered most uncleared portions of the Blue Ridge at that time. Logging and mining operations ceased within the park after its establishment and the families still living there gradually resettled in nearby areas. Since that time, most of the forest has been undergoing a rapid environmental change, which is the uninhibited process of returning to its natural state. Many of the old homesites are still evident in the park. Solitary rock chimneys, vine-covered foundations, broken-down rail fences, and overgrown apple orchards are only a few of the relics of the mountain farms. Young second-growth forest and thick under brush are taking over the abandoned fields and yards—areas that will take the most time in reverting to the kind of wilderness present before human habitation.

|

| Figure 2. Small mountain farm in the upper reaches of Bacon Hollow as seen from Bacon Hollow Overlook. Many similar farms were present along the eastern slopes and crest of the Blue Ridge at the beginning of the twentieth century. |

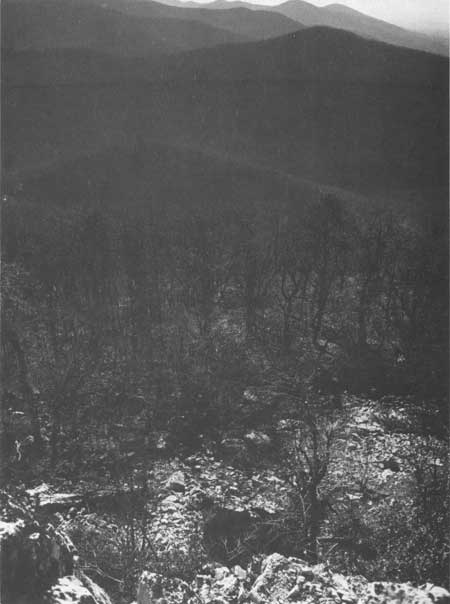

The geology of the Blue Ridge greatly influenced the location of the settlements and the life of the settlers. The early mountain people and probably the Indians before them selected home-sites where water, gentle slopes, and fertile soils were present. This restricted almost all settlement to areas having bedrock of granite or basalt because only in these areas are springs abundant and soils and slopes adequate for small farms. This includes most of the northern half of the park and the eastern ridges in the southern half. The remaining southwestern quarter is largely underlain by metamorphosed sandstone and shale on which soils are very thin and rocky, slopes are steep, and springs intermittent (Figure 3), making the area much less hospitable than that portion underlain by basalt and granite.

|

| Figure 3. Rocky western ridges, which are developed on resistant quartzite beds and phyllite presented an inhospitable environment and were virtually unsettled when the park was established. |

The climate of the Blue Ridge is also influenced by the geology. The elevation of the mountains, directly related to the resistance of the rocks that form them, controls the local climate. In the Blue Ridge temperatures are lower by approximately 5-10° F (2-6° C), and precipitation and wind velocity is greater than in the adjacent lowlands. This more stringent climate probably limited settlement of the Blue Ridge as much as the ruggedness of the mountains. Its importance may be seen in the location of many of the former settlements which were so situated as to obtain some protection from the prevailing southwest or west winds and to receive as much sunlight as possible.

The park provides a look at a thick, mountain-forming sequence of volcanic rock that may be as much as 800 million years old. In the Blue Ridge rapid uplift may have taken place long ago while the rocks were being folded, but now the area is stable and uplift is not evident. The present forms of the mountains and ridges are smooth and rounded except where an occasional quartzite ledge or basalt cliff breaks through the forest cover (Figure 4). The valleys slope progressively more gently away from the mountains into broad, gently rolling lowlands with meandering streams and rivers. This landscape is one of balance or equilibrium where none of the three environmental factors—climate, biology, and geology—that contribute to the formation of the landforms are dominant. The impact of the geology on the origin and environment of the Blue Ridge mountains is subtle because the rocks are masked by soil and forest. Yet, through this cover the individual rock formations express themselves by the shapes and elevations of the mountains they form and by characteristic soils and vegetation.

|

| Figure 4. Hawksbill from Crescent Rock. Rock ledges visible through the trees near the crest of the mountain are generally present on the steep, wooded slopes along the westward-facing Blue Ridge escarpments; they effectively restricted westward movement of the early settlers to the few low gaps in the mountain range. |

The Blue Ridge mountains have been inspirational to man since his first encounter with them. They have been a barrier that had to be surmounted, a refuge from the changing world around them, and a place to replenish the spirit in an ever more rapidly paced world. For these and many more reasons the mountain wilderness of the park must be preserved, but to preserve it we must better know what the Blue Ridge is and why it is there. This, then is a part of the story of the Blue Ridge and of the rocks that form it.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

state/va/vdmr-bul-86/intro.htm

Last Updated: 28-Nov-2007