|

Washington Department of Natural Resources

Geology and Earth Resources Division Information Circular 90

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington

Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue

|

Road Logs

PART 3 - LOWER MONUMENTAL DAM TO ICE HARBOR DAM

| Miles |

|

| 98.1 |

Northwest end of Lower Monumental Dam. Turn

southwest toward Windust.

|

|

|

Back Cover. Route of the field trip. Stop locations are indicated by the

circled numbers. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

| 98.3 |

Entrance to Lower Monumental Dam visitor

parking lot. The visitor area is open April 1 through October

31 for self-guided tours of the fish-viewing window

and the powerhouse. (The visitor area has rest

rooms.)

Continue southwest along the northwest edge of Lake

Sacajawea, the reservoir impounded by Ice Harbor Dam, 50 km farther

down the Snake River. Across the Snake River is a gravel bar deposited

by the Missoula floods.

|

| 100.9 |

East entrance to Windust Park (rest rooms).

Continue west along the north side of the Snake River.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition camped just down-river

of Windust Park in October 1805 (Majors, 1975).

On the opposite side of the Snake River is the

northeast end of the Scott gravel bar (Fig. 39), which extends 9 km along the

southeast side of the river. As much as 6 m of gravel (largest boulder 1 m in diameter) are

exposed in railroad cuts in the giant ripple marks on the Scott bar. In

places there are 2 m of slackwater sediments overlying the gravels,

with perhaps a dozen Touchet Beds exposed. This stratigraphic relation

suggests that the last dozen Missoula floods were going up the

Snake River at this location; if true, the last Missoula floods did not

descend the Cheney-Palouse tract, but reached the Pasco Basin only

by other routes. The flood gravels and Touchet Beds are capped by 1 m of

loess. The ripple marks have a wave length of approximately 150 m;

their amplitude of 6-8 m has been accentuated by gullying of the

troughs.

|

|

|

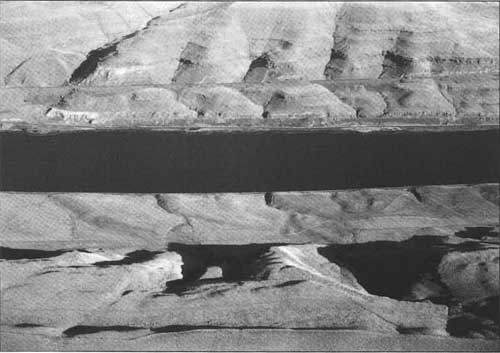

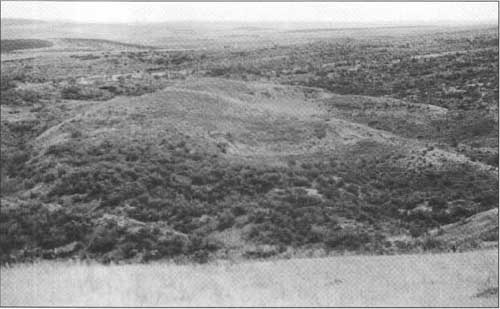

Figure 39. View to the northwest across the Snake River at Scott gravel

bar. The Snake River, which flows from right to left, has cut through

lava flows of the Wanapum Basalt. On the near (southeast) side of the

river is Scott gravel bar, deposited by the Missoula floods. The troughs

of the giant ripple marks have been accentuated by gullying. (See text

for details.)

|

|

| 103.7 |

Leave the Snake River. Turn right (northwest)

under a railroad bridge.

|

| 103.8 |

On the southwest side of the road are sediments

deposited by the Missoula floods in the eddy that existed at the mouth

of Burr Canyon.

|

| 104.7 |

Exposures of Touchet Beds, the slackwater sand

and silt deposited by the Missoula floods.

|

| 106.4 |

Turn left (southwest) onto the

Kahlotus-Pasco highway (elevation 1,215 ft). Drive southwest

through a portion of the Palouse Hills, which are underlain by

Quaternary loess as much as 75 m thick. Kahlotus is about 20 km to the

right (northeast).

|

108.6

to

115.2 |

Crests of hills (elevations about

1,420 ft and 1,195 ft, respectively). Visible

in the distance to the southeast is the crest of the Blue Mountains

anticline, a northeast-trending uplift of Miocene basalt flows. To the

south and southwest are hills along the Olympic-Wallowa lineament

(OWL).

Also visible to the southwest from mile 107.2, and

present only 2 km west of mile 113.8, are the Juniper Dunes (Figs.

40-43). The Juniper Dunes Wilderness is administered by the Spokane

District of the Bureau of Land Management. Information about the Juniper

Dunes and a permit to visit this area can be obtained from the Bureau

(East 4217 Main Ave., Spokane, WA 99202, phone (509) 353-2570). The

wilderness area is 'landlocked' in that access is across private lands.

Permission to cross private land must be obtained in advance from the

landowner.

Much of the dune field was made a wilderness in 1984;

land uses (sometimes in conflict) of the Juniper Dunes include wildlife

habitat, agriculture, nonmotorized recreation, and off-road vehicle

activity. The dunes support grasses, shrubs, and western juniper trees

(Juniperus occidentalis).

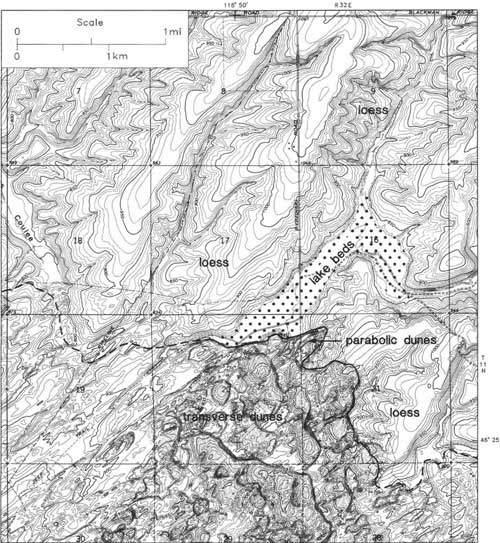

Much of the Juniper Dunes is characterized by

transverse dunes (Figs. 41 and 42), which form where there are fairly

large supplies of sand. Slip faces of these dunes are oriented northwest

and are a maximum of 40 m high. The sources of the sand are in the Pasco

Basin: the Pliocene Ringold Formation (Newcomb, 1958), Pleistocene

glaciofluvial sediments (including the Touchet Beds), and Holocene

alluvium.

At the leeward (north-northeast portion) of the

Juniper Dunes are overlapping parabolic dunes (Fig. 43). One advancing

parabolic dune has buried an old fence. Parabolic dunes have horns that

point upwind and form on either side of a blowout or hollow created when

an unstable portion of the dune migrates downwind (Cooke and Warren,

1973). In general there is more vegetation stabilizing the parabolic

dunes; large parts of the transverse dunes are completely free of

vegetation.

The orientation and asymmetry of the transverse and

parabolic dunes reflect the prevailing southwesterly winds. During

occasional periods of sustained northerly winds, the transverse dunes

become reversing dunes—sand blown up the large slip faces forms

crests with south-facing slip faces. The ripple mark asymmetry reveals

the direction of the most recent wind strong enough to move the sand.

Occasionally the right wind and moisture conditions reveal the giant

cross beds inside the dunes.

Along the leading (northeast) edge of the Juniper

Dunes, intermittent streams flowing southwest from the Palouse Hills

have been blocked by the advancing dunes (Fig. 40). Fine sediment

underlies the flat floors of the intermittent lakes.

|

|

|

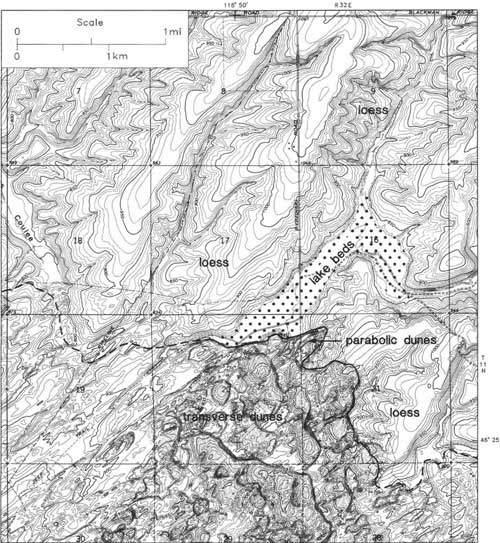

Figure 40. Part of the Levey NW

7.5-minute topographic map (1964 edition) showing surficial geology at

the leading edge of the Juniper Dunes. Intermittent lakes form where

intermittent streams flowing southwest from the Palouse Hills are

blocked by northeast-migrating Juniper Dunes. The higher areas of the

Palouse Hills are composed of loess, but in lower places, there may also

be Missoula flood deposits. Note that the topography here is below the

1,200-ft elevation reached by the Missoula floods at Wallula Gap. Before

this area was invaded by the Juniper Dunes, it was overtopped by

Missoula floods. In addition to loess here, there are Touchet Beds with

clastic dikes and erratic clasts. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Figure 41. View westerly of the northern portion of the Juniper Dunes.

The slip faces of the transverse dunes face northeast in the direction

of slow migration (from left to right). See text for details. The dark

areas in the upper left are irrigated fields.

|

|

|

Figure 42. View upwind (southwest) of transverse dunes, Juniper Dunes

Wilderness. The maximum slip-face height is 40 m. Note the relative lack

of vegetation, except for the juniper trees in the distance.

|

|

|

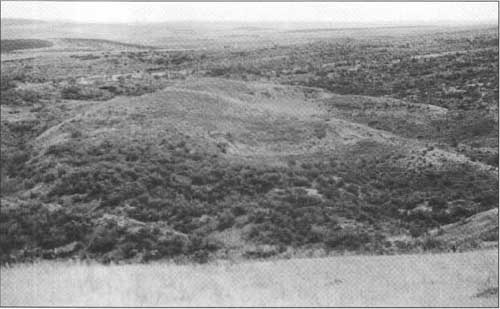

Figure 43. View downwind (northeast) of parabolic

dunes at the leading edge of Juniper Dunes. One parabolic dune overlaps

another. These dunes support considerable vegetation, particularly

sagebrush. In the foreground is the crest of a transverse dune. In the

background are the Palouse Hills of Quaternary loess.

|

|

116.2

to

117.5 |

Roadcuts in Quaternary loess. Our route is

southwesterly into the Pasco Basin, which is structurally and

topographically lower than the Palouse Hills to the northeast and the

anticlinal ridges to the south. The Missoula floods were hydraulically

ponded by the constriction of Wallula Gap where the Columbia River

leaves the Pasco Basin. The highest hydraulic lake surface was at an

elevation of about 366 m (1,200 ft) (O'Connor and Waitt, 1994, p. 38).

Because the elevations here are only 1,100 to 900 ft. we are lower than

the maximum elevations of the floods. There has been reworking of the

top of the loess, and some erratics are present.

|

| 120.4 |

Intersection with Murphy

Road (elevation 797 ft). Continue south on the Kahlotus-Pasco

highway. Vegetation subdues the dunes just to the northwest. This is the

southeast edge of the Juniper Dunes. The dune field has an area of about

130 km2.

|

| 125.3 |

Intersection with Levey Road (elevation 700

ft). Continue west on the Kahlotus-Pasco highway. The geological

materials underlying this 'terrace' between the Juniper Dunes and the

Snake River can be viewed by turning left (southeast) on Levey Road.

Nearby is a gravel pit with excavations in Missoula flood deposits.

Beneath the late Pleistocene sediments, basalt forms a cliff facing the

Snake River. The flows here belong to the Frenchman Springs Member of

the Wanapum Basalt and the Pomona and Elephant Mountain Members of the

Saddle Mountains Basalt (Swanson and others, 1980). Touchet Beds are exposed in railroad cuts

between the cliff and the river.

Levee Park, which has rest rooms, is 1.5 mi from the

Kahlotus-Pasco highway.

|

| 126.8 |

Turn left (south) toward Ice Harbor Dam.

|

| 129.2 |

Railroad underpass.

|

| 129.5 |

Roadcut on the north reveals late Pleistocene Touchet

Beds with clastic dikes and a thin cap of Holocene loess. From north to

south across Ice Harbor Dam are the lock, a fish ladder, the spillway,

the powerhouse, and another fish ladder (Figs. 44 and 45). Miklancic

(1989a) summarized the engineering geology of Ice Harbor Dam.

|

|

|

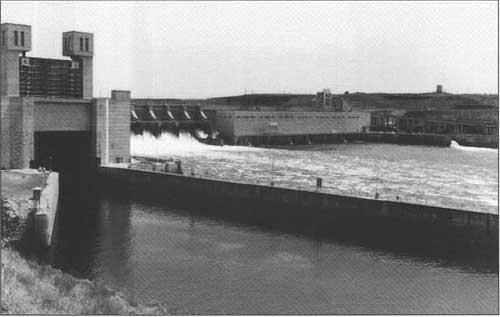

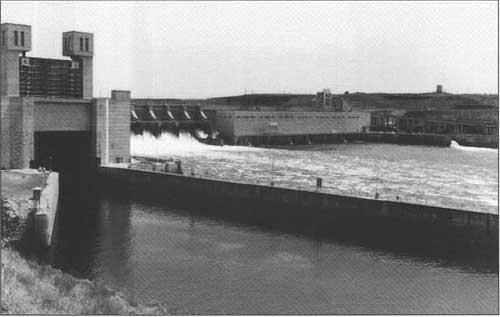

Figure 44. Ice Harbor Dam, Snake River (Stops 8 and

9). This view toward the east shows (from left to right) the lock,

spillway, powerhouse, and south fish ladder.

|

|

|

Figure 45. View down (west) the Snake River at Ice

Harbor Dam. The powerhouse, spillways, and lock are visible from left to

right.

|

|

| 129.6 |

Turn left toward boat ramp.

|

| 129.9 |

Continue east on the primitive dirt road from

the northeast corner of the parking area for the boat ramp. (An

alternative is to park here and walk 0.6 mi to the end of the dirt

road.) At the two junctions on the dirt road, go either way, proceeding

eastward along the north side of the Snake River.

|

| 130.5 |

Stop 8: Park here at the end of the dirt road.

(The small parking/turn-around area is between an abandoned

railroad grade and the Snake River.) Walk east about

300 m along the railroad grade.

Beware of rattlesnakes and ground hornets.

The geology here is described by Swanson and Wright

(1976, p. 8-9; 1981, p. 22). At this stop are some of the youngest

lava flows of the Columbia River Basalt Group. In railroad cuts are

exposed flow contacts, dikes, and an invasive flow.

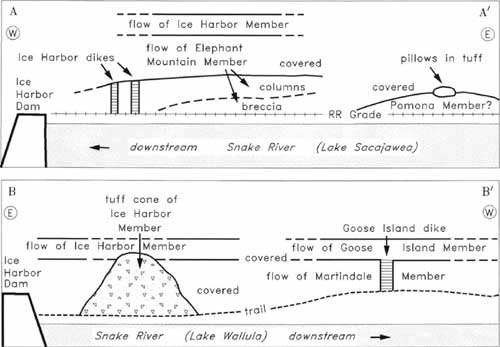

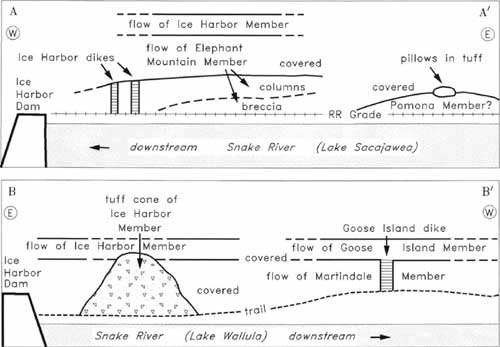

Stop 8A: Western railroad cut (Fig. 46, section

A—A'). In the western railroad cut, a flow of the Elephant Mountain

Member is cut by the Ice Harbor dikes. The dikes, and tuff cone at Stop

9, are part of an 80-km-long linear vent system for the Ice Harbor

flows (Swanson and others, 1975). Above the railroad cut is an Ice

Harbor flow.

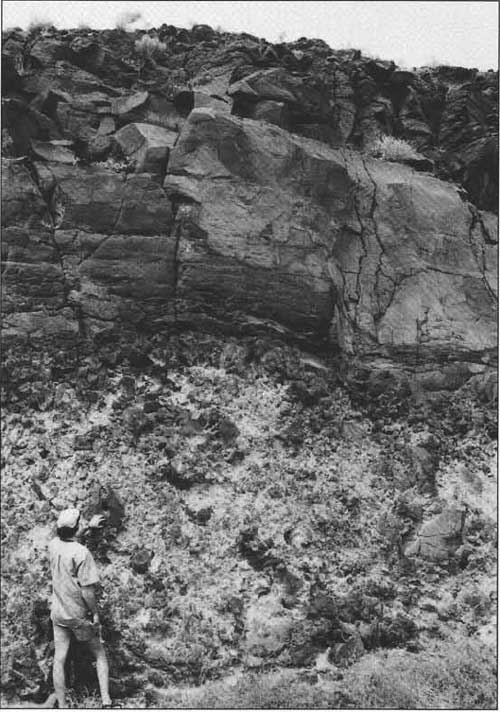

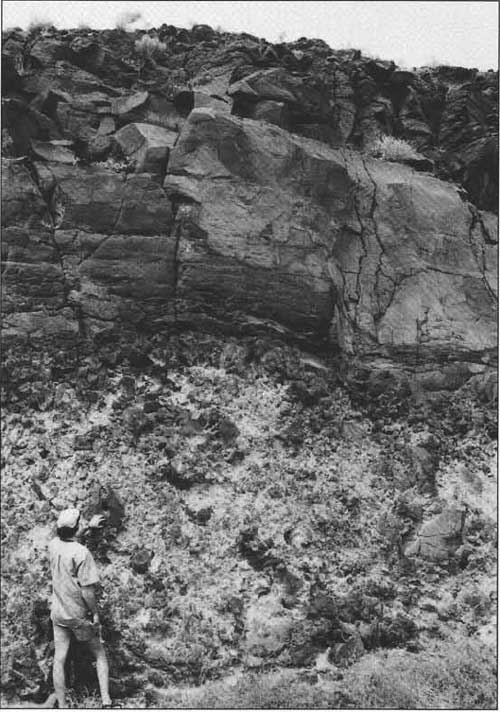

In the railroad cut, the Elephant Mountain flow has

large columns, a vesicular top, and a thick breccia at the bottom (Fig.

47). The breccia, which exhibits ropy texture in places, was described

by S. P. Reidel and Karl Fecht (Westinghouse Hanford Co., unpub. data.,

1987): "The base is, in part, a 'rubble' zone with chilled blocks of

basalt mixed with sediment."

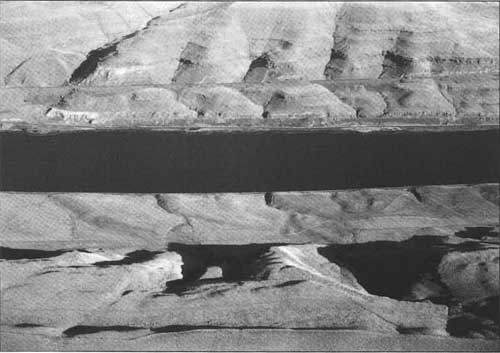

Stop 8B: From the east end of this railroad cut, walk

approximately 250 m east along the railroad grade to the next railroad

cut (Fig. 46, section A—A'). Here the Pomona flow has invaded a

tuff that is exposed at the top of the northern side of the middle of

the railroad cut (Fig. 48). An invasive flow occurs where the

advancing, more dense lava 'submarines' through less dense sediment that is

likely water saturated and of fine grain size. The basalt pillows here

have glassy rims and are surrounded by white vitric tuff. The tuff is

consolidated ash that contains mostly glass particles. The Pomona flow

has large vesicles, some of which are called amygdules because the gas

bubble cavities are filled with minerals such as calcite, quartz, and

zeolites.

Walk back to the end of the primitive road and drive

west toward Ice Harbor Dam.

|

|

|

Figure 46. Diagrammatic cross sections of the basalts in the vicinity of

Ice Harbor Dam. A—A', Stop 8, upstream of the dam, north shore;

B—B', Stop 9, downstream of the dam, south shore. See text for

details. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

Figure 47. Saddle Mountains Basalt east of Ice Harbor

Dam (Stop 8A). The large columns (top) and the thick breccia (bottom)

belong to the Elephant Mountain Member.

|

|

|

Figure 48. Invasive flow east of Ice Harbor Dam (Stop 8B). The Pomona

lava flow formed pillows (dark) where it invaded a less dense tuff

(light). See text for details.

|

|

| 131.2 |

The dirt road becomes paved at the parking lot

for the boat ramp.

|

| 131.5 |

Turn left toward Ice Harbor Dam.

|

| 131.6 |

Begin to cross the dam (daylight hours only).

|

| 132.2 |

Leave dam; turn right (west).

|

| 132.3 |

Turn right (north) toward visitor center.

|

| 132.6 |

Near the bottom of the hill, turn left (west)

toward Stop 9. (The visitor center is to the east.) Proceed downriver on

the gravel road.

|

| 133.6 |

End of the road, Stop 9. Park here and

beware of rattlesnakes and poison oak. Swanson and Wright (1976,

p. 9-10; 1981, p. 23) described the geology of the exposures of

basalt.

Stop 9A (Figs. 49 and 50) is the bluff adjacent to

the end of the road (Fig. 46, section B—B'). This rock is described

by Swanson and others (1975, p. 893) as "crudely bedded, poorly sorted,

palagonitized sideromelane breccia and tuff forming remnant of tuff

cone." (In other words, the fragmental volcanic rock is composed of

altered basaltic glass.) Different dips of the tuff breccia indicate

minor shifting of the vent during construction of the tuff cone, which

is overlain by a slightly younger Ice Harbor flow.

Walk about 700 m west along the south bank of the

Snake River. Along the trail are exposures of tuff, a basalt flow, and

the Pasco gravels.

Stop 9B is the cliff where the trail rises (Fig.

46, section B—B'). The lower Martindale flow is cut

by a Goose Island dike, which feeds the upper flow (Fig. 51) (S. P.

Reidel, Westinghouse Hanford Co. written commun., 1995). The flows and

dike are part of the Ice Harbor Member of the Saddle Mountains Basalt,

dated at about 8.6 Ma. The upper part of the dike is breccia

interpreted by Swanson and Wright (1976, 1981) as drainback rubble.

Walk east to the tuff cone and drive toward Ice

Harbor Dam.

|

|

|

Figure 49. Tuff cone west of Ice

Harbor Dam (Stop 9A). The tuff cone is part of a vent system for the Ice

Harbor flows.

|

|

|

Figure 50. Tuff breccia west of Ice Harbor Dam (Stop

9A). A large clast is visible near the top of this photo. The basalt

tuff breccia makes up a tuff cone that is part of the Ice Harbor

Member.

|

|

|

Figure 51. Flows and dike west of Ice Harbor Dam (Stop 9B). The Goose

Island dike (right of the person) cuts the Martindale flow (small prominent

columns). The dike fed the Goose Island flow (less prominent but larger columns).

|

|

| 134.6 |

Where the gravel road meets the paved road,

continue east to the visitor center.

|

| 134.7 |

Ice Harbor Dam Visitor Center (open all year). Inside

the visitor center are a view of the powerhouse, a window to watch

migrating fish, and rest rooms.

|

state/wa/1996-90/part3.htm

Last Updated: 05-Aug-2011

|