|

Washington Department of Natural Resources

Geology and Earth Resources Division Information Circular 90

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington

Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue

|

Road Logs

PART 4 - ICE HARBOR DAM TO WALLULA GAP

| Miles |

|

| 134.7 |

From the Ice Harbor Dam visitor center, drive

southwest on the paved road toward Pasco.

|

|

|

Back Cover. Route of the field trip. Stop locations are indicated by the

circled numbers. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

| 137.5 |

Intersection with State Route 124 (elevation

530 ft). Turn west (right) toward Pasco. To the south and west there is

a good view of the hills and escarpment that form the

Olympic-Wallowa lineament. The anticlinal hills along the lineament

include Jumpoff Joe (to the southwest), Badger Mountain (to the west),

and Rattlesnake Mountain (to the west-northwest). Rattlesnake Mountain

lies at the south edge of the Hanford Site managed by the U.S.

Department of Energy. Formerly the emphasis of work on the site was on

nuclear weapons and nuclear energy, but today work there centers on

nuclear waste storage and disposal. Considerable funds are being spent

for cleaning up the radioactive wastes.

|

| 141.5 |

Enter Burbank Heights (elevation 411 ft).

|

| 142.7 |

Turn left (southwest) on U.S. 12 toward Walla

Walla. The mouth of the Snake River is 2 km to the southwest. Just

northwest of here is Hood Park (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers). On the

other side of the Snake River, where it joins the Columbia River, is

Sacajawea State Park. The Lewis and Clark Expedition camped at the mouth

of the Snake River in October 1805 (Majors, 1975).

|

| 143.5 |

McNary National Wildlife Refuge. On the northeast side of U.S.

Highway 12 is the northwest end of Burbank Slough, an old meander scar

that was flooded in 1953 when McNary Dam was constructed 50 km down the

Columbia River.

|

| 146.7 |

Cross the southeast part of

Burbank Slough. (You are now in the McNary State Wildlife Recreation

Area.) Wallula Gap is visible 12 km to the south.

|

| 151.5 |

On the west side of the highway is Boise

Cascade's Wallula mill. The chief products are corrugating medium and

paper. Fiber sources are mainly wood chips and sawdust, but soon will

include recycled paper and trees from the huge cottonwood plantation

east of the highway. The genetically identical cottonwood trees, which

are fertilized and irrigated, grow as much as 1 inch in diameter and 10

feet in height per year.

|

| 153.9 |

To the southwest, you can see the delta of the Walla

Walla River (Fig. 52) extending into Lake Wallula along the Columbia

River. When McNary Dam was completed, the reservoir extended up the

Columbia River to Richland and several miles up the Walla Walla River. A

yacht club was established in the 'harbor' along the lower Walla Walla

River. The severe erosion of the Palouse loess and the Touchet Beds

loads the Walla Walla River with a large amount of suspended sediment;

within years the lower Walla Walla River 'silted up', and the yacht club

was moved to Wallula Gap. Now the sediment carried by the Walla Walla

River is deposited in a delta growing out into Lake Wallula (elevation

340 ft).

|

|

|

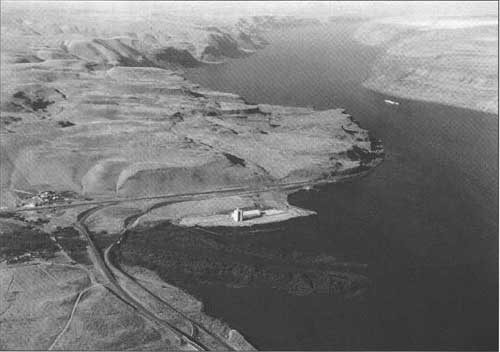

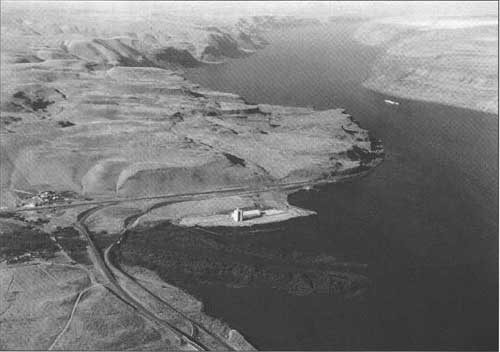

Figure 52. Wallula Gap and the

delta of the Walla Walla River. The Horse Heaven Hills anticline trends

from left to right across the Columbia River. The escarpment in the left

center (facing the viewer) is the trace of the Olympic-Wallowa

lineament. Wallula Gap is a water gap that was too small to accommodate

the entire discharge of the Missoula floods as they traveled south from

Washington (in the foreground) to Oregon (in the background). The

construction of McNary Dam formed Lake Wallula, into which the Walla

Walla River is building a tree-covered delta.

|

|

| 154.2 |

Entrance to Madame Dorion Park on the left (east).

(There are rest rooms here.) Madame Dorion was an Iowa Indian who left

Missouri in 1811 and arrived at Wallula in January 1812 with the Wilson

Price Hunt party of the Pacific Fur Company (information from sign at

park).

|

| 154.5 |

Cross the bridge over the mouth of the Walla Walla

River. At the 'Y' turn west (right) on U.S. Highway 730 toward Umatilla.

This is Wallula Junction (elevation 400 ft).

|

| 155.4 |

STOP 10: Olympic-Wallowa lineament. Park

on the north (right) side of U.S. 930 and be careful of traffic.

Raisz (1945) proposed the term Olympic-Wallowa lineament (OWL) for

a northwest-striking feature stretching 600 km from Cape Flattery in

northwestern Washington to the Wallowa Mountains in northeastern Oregon

(Fig. 2). A segment of the OWL called the CleElum-Wallula deformed

zone (CLEW) is marked by anticlines that trend N50°W. The

Rattlesnake-Wallula alignment (RAW) is the part of the OWL and

CLEW that forms the southwestern boundary of the Pasco Basin (Reidel and

Lindsey, 1991).

The hillside to the south of this stop is the

northern escarpment of the Horse Heaven Hills, a long, broad anticlinal

ridge that stretches across southern Washington from the Cascades to

Wallula Gap. From Wallula Gap, the ridge trends east-southeast and

intersects the Blue Mountains near Milton Freewater, Oregon (Fig.

52).

West of Wallula Gap, the OWL is expressed as

northeast-facing fault scarps that extend northwestward along the flank

of the Rattlesnake Hills. East of the gap, faceted spurs marking the

northern boundary of the Wallula fault zone constitute the OWL (Fig.

53). The OWL is the topographic expression of a zone of high-angle

faults along which Miocene basalts are in the upthrown block to the

south and Quaternary sediments are in the downthrown block to the

north.

In Washington, the maximum relief across the OWL

occurs about 65 km to the northwest of here. On the northeast side of

Rattlesnake Mountain (elevation 3,524 ft) there is about 900 m of

relief, but much of that relief is due to the anticlinal fold and only

in part to faulting. To the southeast of Wallula Gap, there is a fault

scarp in the southeastern corner of the Zanger Junction quadrangle

(1:24,000) that exceeds 100 m. Farther southeast in Oregon, the relief

along the OWL along the northeast side of the Wallowa Mountains is more

than 1,500 m.

Examine the subparallel faults (part of the much

wider Wallula fault zone) in the basalt in the roadcut on the south side

of U.S. Highway 12 (Fig. 54). The lava is the Two Sisters unit of the

Frenchman Springs Member of the Wanapum Basalt (Gardner and others,

1981). The Two Sisters unit is equivalent to the Sand Hollow unit of

south-central Washington (S. P. Reidel, Westinghouse Hanford Co.,

written commun., 1995). Note the fault breccia and yellowish fault gouge

along each of the near-vertical faults. Along the western fault are

subhorizontal slickensides that indicate that the last movement was

strike-slip (Fig. 55). About 8 km to the east, a fault on the southwest

side of Vansycle Canyon appears to deflect intermittent streams as much

as 250 m; the offset drainage suggests right-lateral strike-slip

movement (Gardner and others, 1981). However, nearby drainages and

ridges are not as deflected, so the apparent offset drainage may be due

to local erosion along the fault plane (Reidel and Tolan, 1994, p.

1638).

The age of the most recent movement along the faults

that form the OWL is not known with certainty. Carson and others (1989)

found evidence for deformation along the OWL on the northeast side of

the Wallowa Mountains; the Enterprise Gravels (about 2 Ma) have been

tilted. Mann and Meyer (1993) argue that there has been some

right-oblique slip displacement along the OWL in the Holocene. Their

assessment is based in part on what they interpret as a 5-m offset of a

Mount St. Helens ash (dated at 10.7 ka) between here and

Milton-Freewater, Oregon. Also near Milton-Freewater there was an

earthquake of approximately magnitude 6 in 1936 (Brown, 1937), but

that earthquake may have been associated with the Hite fault (Fig. 2)

rather than the OWL (Reidel and Tolan, 1994, p. 1636).

The delta of the Walla Walla River, visible less than

a kilometer to the northeast, is advancing into Lake Wallula.

On the floor of Lake Wallula is the April 1806

campsite of Lewis and Clark. They described the "Wallah wallah River"

as "a handsom stream about 4-1/2 feet deep and 50

yards wide." When members of the Lewis and Clark expedition danced to a

fiddle, the "chimnahpoms" (Yakima Indians) and "wollahwollahs" sang and

joined the dance (Majors, 1975).

A bit farther north, and also now submerged, Fort Nez

Perce (also known as Fort Walla Walla) was established in 1818. The log

fort burned in 1841 and was replaced by an adobe fort that washed away

during the Columbia River flood of 1894 (Majors, 1975). That flood had a

recorded discharge of 34,000 m3/sec (1,200,000

ft3/s). The mean discharge of the Columbia River (at

Bonneville) is 5,266 m3/sec (185,900 ft3/sec). Of

this discharge, 1,446 m3/sec (51,060 ft3/sec) is

contributed by the Snake River (Bonneville Power Administration,

1993).

Contrast the 1894 floodflow with Baker's (1973b)

estimate for a typical Missoula flood of

21,000,000 m3/sec (740,000,000

ft3/s). (This is about 18 mi3 of

water per hour!) These floods poured into the Pasco

Basin from the northeast, north, and northwest, but the only outlet was

Wallula Gap. At less than 2 km wide, Wallula Gap could accommodate only

about half of the peak discharge of a Missoula flood. Therefore, the

water level in the Pasco Basin rose rapidly to 1,200 ft. This formed

Lake Lewis, which lasted about a week during each Missoula flood (Allen

and others, 1986). Lake Lewis backed east and west up the Walla

Walla and Yakima Valleys, respectively; in these arms of

the lake accumulated thick slackwater sediments, or the Touchet Beds.

The bottom of the Columbia River has an elevation here of about 300 ft.

Imagine 275 m (900 ft) of water rushing through Wallula Gap at velocities

of as much as 80 km/hr (50 mph) (Allen and others, 1986).

Continue southwest on U.S.

Highway 730 through Wallula Gap (Fig. 56).

|

|

|

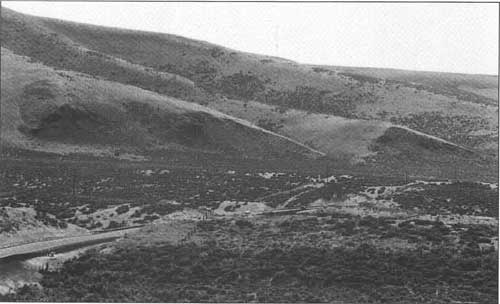

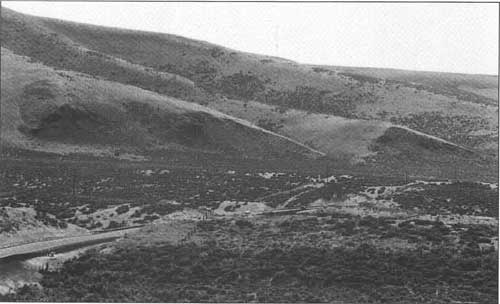

Figure 53. The Wallula fault zone east of Wallula

Gap. Movement along the fault zone has created the escarpment that forms

part of the Olympic-Wallowa lineament. Here on the north flank of

the Horse Heaven Hills anticline, the Wallula fault zone is marked by a

line of triangular faceted spurs with exposures of basalt. In the

foreground the floor of the lower Walla Walla River

valley is underlain by Touchet Beds.

|

|

|

Figure 54. Fault at Wallula (Stop

10). This high-angle fault is part of the Wallula fault zone. This is

one of a group of subparallel faults marked by subhorizontal

slickensides, lineations, breccia, gouge, and accelerated

weathering.

|

|

|

Figure 55. Close view of the fault in Figure 54 (Stop

10). The fault trace is from upper left through the hammer to lower

right. The lower left side of the fault is somewhat brecciated basalt.

Above the hammer are faint slickensides (parallel to the hammer head)

indicating that the last fault movement was subhorizontal.

|

|

|

Figure 56. Wallula Gap on the Columbia River (view north). Parts of

the Grande Ronde, Wanapum, and Saddle Mountains

Basalts are exposed at Wallula Gap. The elevation of Lake Wallula is 340

ft. In the far distance is the Pasco Basin. The distant cliffs on the

east side of the river rise to 783 ft; they were overtopped by the

Missoula floods, which cut channels farther to the right (east). The

cliffs on the west side of the river reach 1,147 ft; even this elevation

is below the 1,200 ft estimated as the upper limit of the floods.

|

|

| 156.6 |

The Two Sisters stand above the east side of

U.S. Highway 730 (Figs. 57 and 58). These buttes are scabs or erosional

remnants of basalt (Frenchman Springs Member) left after passage of the

Missoula floods. Each butte is part of the entablature of a basalt flow

whose colonnade is at the base of the buttes.

The uppermost limit of flood scour at Wallula Gap is

about 1,200 ft (Waitt and others, 1994). The largest flood channel

adjacent to Wallula Gap is east of the Two Sisters (Fig. 57). Huge

volumes of water rushed south there, creating an area of 'channeled

scabland' with a floor at 500 ft. At the south end of that channel,

from the Two Sisters to the Columbia River and on both sides of U.S.

Highway 730, is a small dune field most of which is in active because it

has been stabilized by vegetation.

|

|

|

Figure 57. View westerly across the Columbia River at Two Sisters. The

Missoula floods traveling down the Columbia River (from right to left)

cut this part of the Channeled Scabland. The Two Sisters are the two

buttes (erosional remnants) by the river in the left center. See text

for details. A small dune field is visible as is side of the Two

Sisters.

|

|

|

Figure 58. Two Sisters, Wallula Gap. These are

erosional remnants of basalt left by the Missoula floods. These scabs

are cut from the Frenchman Springs Member of the Wanapum Basalt. The two

buttes are part of the entablature of a lava flow. The colonnade, about

5 m high, is popular for rock climbing.

|

|

| 157.4 |

The basalt exposure on the east (left) side of

U.S. Highway 730 is followed by a roadcut that exposes a lens of Mazama

ash about 1 m thick. This lava flow is near the bottom of the Frenchman

Springs Member of the Wanapum Basalt. To the southwest, between the

road and the river, is the uppermost flow of Grande Ronde Basalt

(Gardner and others, 1981).

Notice the huge talus slopes on both sides of the

Columbia River. It is likely that the high-discharge, high-velocity

Missoula floods removed all unconsolidated debris from Wallula Gap, so

all this talus has accumulated in the last 12,700 years.

|

| 160.6 |

Washington-Oregon state line. Continue

southwest on U.S. Highway 730.

|

| 161.4 |

STOP 11: View of Wallula Gap (Fig. 56). Park on

the left (southeast) side of U.S. 730. Be careful of

traffic!

Parts of the Grande Ronde,

Wanapum, and Saddle Mountains Basalts are exposed at Wallula Gap

(Swanson and others, 1980). A thick section of the Frenchman Springs Member

of the Wanapum Basalt is overlain by the Umatilla Member of Saddle

Mountains Basalt. A Martindale flow of the Ice Harbor Member (about 8.5

m.y. old) of the Saddle Mountains Basalt caps the highest point visible

on the northwest side of the Columbia River. This does not mean that

there is a complete section of the Columbia River Basalt Group exposed

here. The cliffs at Wallula Gap are a maximum of 300 m high, but the

total thickness of the Columbia River basalts is thousands of meters.

More than 300 individual flows are known (Tolan and others, 1989), but

only about 20 flows have been recognized in the vicinity of Wallula Gap

(Gardner and others, 1981, p. 6).

The Martindale flow overlies gravel compositionally

similar to that at Stop 7. Therefore, we can conclude that the

Clearwater-Salmon River was cutting across the Horse Heaven Hills

here by 8.5 m.y. ago (Swanson and Wright, 1981). At that time the course

of the Columbia River was about 80 km (50 mi) northwest of Wallula Gap.

There has been considerable debate about why the Columbia River shifted

east to Wallula Gap.

Fecht and others (1987, p. 238) "...believe that

continued subsidence of the central Columbia Plateau centered in the Pasco

Basin and uplift of the Yakima folds, specifically the Horse Heaven

Hills, were important factors in the diversion of the Columbia River"

and its capture by the Clearwater-Salmon River. Fecht and

others (1987) described the paleodrainage of the Columbia

River system and summarized the history of the theories about why

the Columbia River shifted eastward from the central Pasco Basin to

Wallula Gap.

At road level are lava flows of the Frenchman Springs

Member (about 15.5 Ma) of the Wanapum Basalt. Note the following: the

flow contact with flow-top breccia and ropy texture, which is called

pahoehoe; the difference between polygonal contraction columns in the

entablature and the basal colonnade; and the presence of phenocrysts,

vesicles, and amygdules. The pahoehoe flows of the Columbia River

basalt were very fluid; rapid cooling of the flow surface produced a

smooth or ropy texture. As the molten interior continued to move, the

surface was cracked and broken, and solid fragments became incorporated

in the molten part of the flow. The upper part of a flow that consists

of these fragments is called a flow-top breccia. The top of the flow and

(or) some fragments may be arranged so that they resemble ropes laid

side by side or mixed together. The geological contact where a younger

flow overrides the older flow-top breccia may be a reddish zone, due to

oxidation. Phenocrysts are large crystals (commonly the mineral

plagioclase) that crystallized in the lava before it erupted. Vesicles

are cavities that formed by bubbles of volcanic gases; amygdules are

vesicles that were filled by minerals such as calcite, quartz (or opal),

or zeolites.

Return to the Oregon-Washington state line by

driving northeast on U.S. Highway 730. We now start the last leg of the

field trip.

|

state/wa/1996-90/part4.htm

Last Updated: 05-Aug-2011

|