|

Gila Cliff Dwellings

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter IV:

HISTORY OF ARCHEOLOGY UNTIL 1962

The shelf of documented archeology at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument and the surrounding area is short: in brief, excavation was primarily to salvage artifacts and was usually a byproduct of efforts to stabilize architecture at the cliff site. The reasons for the brevity and informality of archeological investigation are relatively complex, however, and stem in varying proportions from remote geography, the historical and theoretical evolution of archeology in the Southwest, and common as well as official perceptions about ruins on the headwaters of the Gila River.

Amateurs, Vandals, And Mummies

The first published record of a cultural site on the upper Gila is the brief hand-lettered notation "Cliff Dwellings" on an 1884 subdivision map of Township 12 South Range 14 West of the principal base and meridian in the territory of New Mexico. [1] This map also depicts within two miles of the prehistoric site five cabins up and down the West Fork of the Gila River and a road between the mouth of the unnamed canyon that contained the dwellings and the cultivated and irrigated land of a man named Rodgers, not far from the present Heart Bar headquarters. In view of these improvements, the surveyor was obviously not the first citizen to see the cliff dwellings.

In fact, Henry B. Ailman had already visited these ruins in 1878 during a very informal prospecting trip to the headwaters of the Gila. In his memoirs, written years after the visit and published only posthumously in 1983, his description of the prehistoric site documents an unfortunate but common American activity: he looked for relics. [2] In this case, Ailman found only small corncobs, although the following year he reported that other men found the swaddled desiccated body of an infant, which was brought out of the wilds, photographed, and shipped to the Smithsonian Institution. There is no record, however, of those remains in Washington D.C. [3]

The record of amateur collecting at Gila Cliff Dwellings continues in the Black Range Tales, a memoir by James B. McKenna that was published in 1936. [4] He also was a prospector, and he had homesteaded on the Gila River above the Gila Hot Springs in 1884, the same year as the subdivision survey. By his recollection, he and friends found many artifacts at the dwellings: grooved hammers and axes of stone, finely crafted turquoise beads, and another infant mummy, wrapped in "cottonwood fiber," which also was reportedly sent to but never received by the Smithsonian. [5]

In the summer of 1885, Lieutenant G. H. Sands also paused to dig at Gila Cliff Dwellings as troops of the 4th and 6th cavalrys were maneuvering in the wake of an Apache raid that left 35 settlers dead along the tributaries of the upper Gila. Excerpted in El Palacio magazine in 1957, the account has an odd idyllic tone, at least in light of those then recent and dismal events, which were not mentioned in the account. [6] Nor is any mention made of the homestead cabins that were along the river, including an adobe house at the hot springs where Sands only reported seeing wickiups. Our own assessment of the soldier's excited discovery of cliff dwellings in a narrow canyon romantically hidden by vines and through which he carved his way with a knife must include the fact that this canyon lay at the end of a wagon road that began about a mile downstream at irrigated fields. Despite the assault of a mountain lion that knocked off his hat, Lieutenant Sands—and some companions—explored the ruins, and digging with their knives turned up arrowheads and pieces of pottery that were decorated "by a peculiar and uniform system of lines and lozenges."

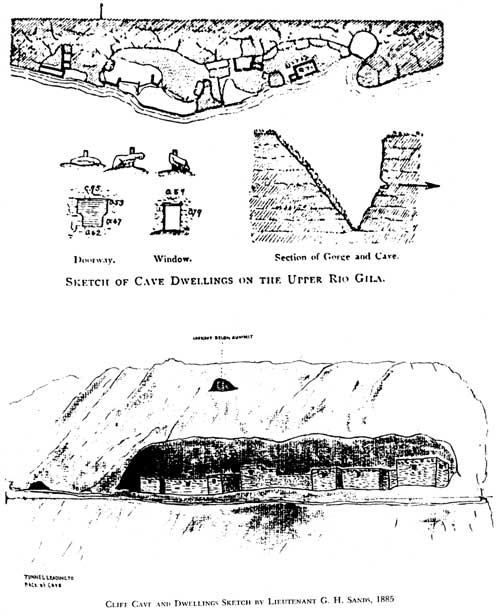

A sketch that bears little congruity with the ruins and the other anomalies may reveal more about selective and romantic idiosyncracies of memory than about Gila Cliff Dwellings. The account also reflects the influence of popular archeological literature such as John Stephens' Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan; the widely read magazine articles of Frank Cushing about his exotic and double life among the Zuni as an ethnologist for the Smithsonian Institution and as First War Chief of the tribe; [7] and the beautiful photographs taken by William H. Jackson of the mysteriously abandoned cities that he had discovered hidden in the cliffs of the American Southwest. Lieutenant Sands remembered an adventure, but the setting was probably drawn equally from the Gila River and from the library.

The Conquest of Peru by Walter Prescott had a more immediate and demonstrable effect on prehistoric remains along the Gila River, according to William French, a nineteenth-century rancher and memoirist. [8] He wrote of digging with a friend for golden pots and utensils in a cliff dwelling on the West Fork. [9] Having recently read Prescott's history of the Incas and of their treasure, French's companion presumed all ancient Indians to have had a surfeit of gold lying around, treasure likely to be discovered in cliff dwellings, as well. All the men found, however, were a few stone tools, painted bows, and corn that they were unable to smash with a rock.

"Those romantic historians had a lot to answer for," French concluded.

|

| These drawings of Gila Cliff Dwellings were based on contemporaneous visits by Adolph Bandelier and Lieutenant Sands in the mid-1880s. The pictures reveal how the biases of interest, training, and memory shape perception. |

In 1892, the Chicago Tribune printed an article about a third child-mummy that had been recovered three years earlier near Gila Cliff Dwellings, this time by the Hill brothers, who were operating a small resort at the Gila Hot Springs and already bringing tourists to the nearby archeological sites. [10] This story, which was also printed in St. Louis and Tucson, included a detailed description of an apparently deformed four-year-old and an interesting conjecture: the child had been abandoned and had died of starvation. Implicit in this conjecture is the idea that the mummy had not been dug from the earth; after all, a burial can hardly be construed as an abandonment. If the dead child lay exposed and in plain sight, on the other hand, a question arises as to why it hadn't been discovered by the ransackings of earlier visitors. One possibility entails the cultural site LA 10048, a vandalized Apache burial, [11] where a short yucca stalk platform still lays beneath an overhang, 150 feet or so up the canyon wall opposite the cliff dwellings. If the Hill brothers recovered their mummy from the hidden but possibly unscavenged yucca platform, and the word burial is more loosely interpreted as funereal, the issues of construed abandonment and of visibility despite late discovery would become compatible.

Unfortunately, the location of these remains is also unknown. Like the other mummies, it was sent to the Smithsonian, where there is no record of it either. In this case, however, the dispatch of the remains is corroborated by a Silver City Enterprise account, which laments the fact that the newspaper was not able to acquire such an important relic for local edification, [12] and by Benjamin Elmer Pierce, the son of the Rev. R. E. Pierce who photographed the cadaver in 1892. [13] That none of the child-mummies dispatched to the Smithsonian arrived seems curious, and a brief inquiry into documentation reveals some additional parallels. While both Ailman's mummy and that of the Hill brothers were purportedly photographed, for example, the only photograph of a mummy in Ailman's scrapbook—presumably the one "which is in my reach as I write [the memoirs]"—is the one that Pierce made. [14] No photograph is known to exist for McKenna's despite its reported and presumably tempting display behind glass at Hinman's hardware store in Silver City. Furthermore, neither Ailman's mummy nor McKenna's has independent corroboration. According to the 1892 newspaper account, in fact, the Hill brothers' mummy is "the first one discovered which may reasonably be supposed to be one of the extinct race of cliff dwellers." The accounts of Ailman and McKenna were written years after their visits to the cliff dwellings, long after the well-reported discovery of a mummy. Is it possible that a good story was too much to resist including in a memoir and that only one child-mummy was ever discovered and sent and lost on its way to the Smithsonian?

The most sensationalized amateur find at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument was the report in 1912 by Gila National Forest staff of a "fourth" child-burial that generated the article in Sunset magazine about an 8,000-year-old ancient race of dwarfs on the headwaters of the Gila River. "Zeke," as the magazine writer dubbed the mummy, was the first and only mummy to reach the Smithsonian, where it was described by Walter Hough as the body of an infant. [15]

Early Scientific Archeology

The distinction between professional and lay interest in prehistoric remains is vague for the years before American archeology emerged as a scientific discipline. The initial inclination even of Henry W. Henshaw, the naturalist who first recorded cliff dwellings on the West Fork, had been to dig as Lieutenant Sands did with a knife and fingers. Henshaw dug for skeletons as ranchers along the Mimbres River also did not too long afterwards. [16]

In 1878 a fifteen-page circular [17] was published by the Smithsonian and thousands of copies were distributed in an effort to mitigate the isolated and disconnected nature of archeological work occurring. [18] It outlined standardized techniques of recording data and also solicited the contribution of specimens that had been so documented. The long-range goal of the circular was to produce "an exhaustive work upon our North American antiquities." From the upper Gila area, a collection was sent and a correspondence begun that same year by Lt. Henry Metcalf, a local rancher who had explored Greenwood Cave on a tributary of the Gila River. [19] The following year, H. H. Rusby, a botanist from New Jersey who had come west "in search of botanical novelties" and to investigate natural history and archeology in New Mexico also made a collection of relics for the National Museum from Greenwood Cave, between jobs and before his departure for Mexico. [20]

The disparate backgrounds of Lieutenant Metcalf and Rusby and the incidental nature of their collections—only part of the soldier's went to the National Museum, for example—underscores the essentially random character of archeological data that was being sent east for preservation, display, and study.

In 1879, the year following the Smithsonian circular, systematic archeological research finally began in the American Southwest. The Bureau of American Ethnology was established, with John Wesley Powell as its chief, and such scientific societies as the Archaeological Institute of America were organized. Powell immediately dispatched a group of ethnologists to an area that he had visited during his own explorations of the Colorado River: the western pueblos of the Southwest, including Zuni. A junior member of that expedition was 22-year-old Frank H. Cushing, who stayed at Zuni for five unanticipated years, assimilating himself into the tribe—a novel and professionally unsanctioned venture in the years before Malinowski staked his tent and his reputation in a village of South Sea Islanders and formalized the precept of participant observation.

Meanwhile the Archaeological Institute of America asked the renowned anthropologist Henry Lewis Morgan to develop a plan of research. Shortly afterwards, his protege, Adolph F. Bandelier was hired to survey ruins in the Southwest. Older and less flamboyant than Cushing, Bandelier was still equally intrepid, and he spent five years, usually on foot, wandering about the still dangerous territories of New Mexico and Arizona in search of ruins, armed only with a steel yardstick, a pen, and paper.

For years after the initial work of Cushing and Bandelier, Southwestern archeological activity was guided by techniques of ethnological analogy, direct historical approach, and the unilineal theories of cultural evolution expounded by Henry Lewis Morgan. According to these theories all of the Southwestern pueblos would represent a single level of culture and would be essentially identical. One effect of these theories and methods of research, especially when combined with ethnocentric attitudes about architectural scale and technique, was to concentrate later archeological expeditionary work in the Four Corners area, where the largest abandoned cliff dwellings and pueblos occurred—not far from still occupied pueblos that could be studied as explanatory models. Unfortunately, with most research taking place in the northern part of the state, the archeology of the upper Gila River was essentially neglected for nearly half a century.

Bandelier, Hewett, And Hough

Bandelier's long survey was exhaustive and included all of the American Southwest and substantial portions of northwestern Mexico. The cliff dwellings on the upper Gila, not far from the Gila Hot Springs, were described in the document that he eventually prepared for the Archaeological Institute of America and that was published in 1892 as his Final Report of Investigations among Indians of the Southwestern United States, Part II. By 1907, when Gila Cliff Dwellings were made a national monument, he had written the only formal description of the site, based on a four-day visit in January 1884.

His official report of the dwellings included measurements of wall thickness and the diameter of ceiling beams, a sketched plan, a room count, and an assessment of the architecture's condition which he deemed "quite well preserved." The site was evaluated for its defensive capabilities, a common explanation for cliff architecture, and its vulnerability to siege was noted. In addition, Bandelier made some very general comparative observations: a hearth was similar to those at Pecos; the construction of the roofs was "of the pueblo pattern." These and other similarities concerning the sandals, baskets, prayer-plumes and prayer-sticks that he found—combined, of course with the unilineal evolutionary ideas of his mentor Morgan and with his own observations made at the Santo Domingo and Cochiti pueblos—contributed to Bandelier's conclusion "that their makers were in no manner different from the Pueblo Indians in general culture."

In fact, he thought that the architecture, which in his estimation only accidently approached two stories, might even provide a useful model for the development of terraced houses among the northern Pueblos.

Years later this 1892 description prompted Edgar L. Hewett, who was temporarily employed by the Smithsonian as an assistant ethnologist, to include a picture of the cliff dwellings in a 1904 Smithsonian report entitled "A General View of the Archaeology of the Pueblo Region," and to indicate in the text that the site was "of sufficient importance to demand permanent preservation." [21]

Following Hewett's initial report, the Smithsonian published a series of bulletins to consolidate archeological data from the Southwest and to further facilitate the protection of sites. Bulletin No. 35, Antiquities of the Upper Gila and Salt River Valleys in Arizona and New Mexico, which was written by Walter Hough and published in 1907, reprinted Bandelier's report on the Gila Cliff Dwellings as well as that of Henshaw. Most of the sites recorded, however, were (1) those that had been noted by Hough's colleague Jesse Walter Fewkes around the Casa Grande ruins in Arizona and along the nearby rivers, including the Gila as far as Safford, and (2) those observed during Hough's own Gates-Museum 1905 expedition, which had been designed to extend the earlier work of Fewkes by surveying tributary waters of the Gila in eastern Arizona and western New Mexico—specifically the Blue River and headwaters of the San Francisco. [22] That Hough didn't ascend the main stem of the Gila instead is a historical happenstance, shaped perhaps by difficult geography, roads, finances, and the limited knowledge of his guide.

As a partial result, when the Forest Service participated in 1908 with a survey sponsored by the Bureau of American Ethnology to locate and protect historic and prehistoric sites and places of scientific interest on public lands, Gila Forest Supervisor Frank Andrew could report inaccurately but without challenge that the only such site was Gila Cliff Dwellings, which was already protected by proclamation. [23] In 1911, at the national park conference held at Yellowstone National Park, it was then further misreported that Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument "consists of a group of hot springs and cliff houses in the Mogollon Mountains, neither very large nor very important, but are located in a district in which few prehistoric ruins are found." [24] Just the phrase about hot springs, which do not exist on the national monument, suggests how little the site was known.

Some other inaccuracies of that assessment could have been demonstrated with journal entries that Bandelier made during his brief visit to the upper Gila, informal documents that only emerged into public view gradually, starting in the 1960s. The official report regarding archeological sites on the upper Gila differed from the journal entries by degrees of concision and formality, with a consequent loss of detail. For example, Bandelier excluded from his official document local reports of artifact collecting and his own observations about the rifled condition of the cliff dwellings. More importantly, Bandelier left out descriptions of other sites visited near the cliff dwellings, including what is the TJ Ruin, for which he described the following location:

The ruins are directly opposite Mr. Jordan Rogers' [sic] new ranch, on a perfectly bare hill, about sixty-five meters high over the river. The main Gila there hugs the hills close. The ascent is rather steep, and there is a good deal of loose lava rock, but a good trail, though steep, leads up to it.* This trail is not old, it leads to the Gilita [East Fork] and to a cattle ranch situated on that stream. On the very brow of that hill, facing south, south-southwest and southwest to west even, the ruins are situated, completely overlooking the whole valley, an admirable position for defence and observation, as it is a depressed plain, perfectly bare, so that for nearly a mile, on the elevation itself, not a mouse could move without being seen from the pueblo. The latter is small.... [25]

There Bandelier measured a broken mano, sketched a few sherds, and noted that the walls of volcanic rock laid in earth had all fallen, obscuring the plan of the ruin. He saw enough of the architecture, however, to comment on its similarity in style and design—on a smaller scale—with ruins in the Mimbres Valley. Apparently, the scale was sufficiently smaller so that Bandelier did not include this site in his final report. [26]

Watson And The Advent Of Historical Particularism

In 1927, El Palacio, a magazine founded by Edgar L. Hewett and the New Mexico Archaeological Society to promote archeology and Southwestern culture in general, published a survey by Editha L. Watson of 104 archeological sites along the upper Gila River, some of its tributaries, the Mimbres River, and around the general vicinity of Pinos Altos, an old mining town just north of Silver City. [27] The most detailed site description (#20) was of Gila Cliff Dwellings, the first published description of the place since Hough's reprint of Bandelier's report, and a photograph of the ruins illustrated the title page of the August 27 issue. Corncobs were still plentiful, and Watson also noted the presence of red pictographs, about which she wrote "they are supposed to be the work of later tribes." The source of this supposition is unknown, although she may have discussed the pictographs with Wesley Bradfield, an archeologist with the School of American Archaeology who had begun several years earlier to excavate at a Mimbres ruin near Silver City—work that was also reported in El Palacio—or with C. Burton and Harriet Cosgrove, amateurs from Silver City who were digging at the Swarts Ruin and who would write a report that stood for years as the best description of a Mimbres cultural site.

Like the Cosgroves, Watson was not a university-trained archeologist, but she had a significant collection of Mimbres mortuary pottery that brought her to the attention of Jesse Walter Fewkes, drawing her at least peripherally into professional archeological circles. Fewkes himself had been drawn to the Mimbres area by E. D. Osborne, another local and amateur collector of prehistoric pottery, who had begun a correspondence with the Smithsonian Institution just as Lieutenant Metcalf had more than 30 years earlier.

In her survey, Watson included the TJ Ruin (#23), which was "across the river from the [Heart Bar Ranch] house, on what is called the 'Polo Grounds,'" and noted that the pottery sherds were different from those elsewhere in the Heart Bar range (the West and Middle forks of the Gila) which appeared to have been thickly settled at one time. This observation contrasted with the previously noted assessments of the Forest Service and the Park Service. She also reported without comment that Mr. T. L. Perrine, the manager of the Heart Bar, had excavated another site on the ranch "range" that yielded burials but not the valuable mortuary pottery. Pothunting was common, Watson had written in her introduction, and she recommended that all the sites she identified be excavated or preserved.

Seven years after the 1907 publication of Antiquities of the Upper Gila and Salt River Valleys in Arizona and New Mexico, Jesse Walter Fewkes had commented that "we know practically nothing about the prehistoric cultures of the Upper Gila," and Alfred Vincent Kidder had reiterated the observation, practically word for word, in his Introduction to the Study of Southwestern Archaeology, published another ten years later. In this near void, Watson's survey, which identified many sites that Hough and his informants had not recorded, had little impact and few echoes—not until the 1980s did it even appear in a scientific bibliography. The popular bias of the magazine in which the survey was reported may have contributed to the professional silence, but a larger reason was probably a change that was happening in the theoretical framework of archeology: historical particularism.

The ascendancy of Franz Boas and the influence of his empirical approach to anthropology, actual excavations at Pecos, Pueblo Bonito, and ruins in the Four Corners area, and the new procedures of stratigraphic records and ceramic seriation developed around the time of the First World War shifted professional attention in the Southwest to the creation of relative chronologies for prehistoric sites. This trend was formalized in 1927 as the Pecos Classification System: Basketmaker I, II, III, and Pueblo I, II, III, IV, V. In brief, typologies of architecture and artifacts that had previously been developed for descriptive purposes and the presence or absence of particular traits or phenomena at excavated sites—evidence of agriculture or cranial deformation, for example—were used to sequence chronologically the evolution of pueblo culture.

Published the same month and year of the first Pecos conference, Watson's survey echoed the intent of Hough's 1907 work—the legal protection of antiquities. Twenty years after the passage of the Antiquities Act, her approach was dated. The cursory information was only of anecdotal interest, nearly irrelevant to the new issue of cultural history, and ultimately overshadowed by excavations in 1927 at the Cameron Creek Ruin and along the Mimbres River at the Swarts and Galaz sites.

Cosgroves And The Further Evolution Of Historical Particularism

In 1929, two years after Watson's article in El Palacio, C. Burton and Harriet Cosgrove, the local husband-and-wife team of archeologists sponsored by the Peabody Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts, were on the headwaters of the Gila River, surveying cave and rock shelters and occasionally salvaging the associated prehistoric artifacts. Concerned about the prevalence of vandalism and looting at these kind of sites, their fieldwork eventually included caves in the Hueco Mountains in Texas, caves in far southwestern New Mexico, and Chavez cave on the Rio Grande in southern New Mexico.

Despite extended fieldwork around the forks of the Gila and for reasons not explained in their published analysis, the Cosgroves examined only one site that lies in the national monument—a cave adjoining "on the north the group containing the cliff houses of the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument," [28] which by description is now known as Cave 6 of the linked caves at the monument. [29] At any rate, behind a large boulder, a disturbed burial was found, the remains of a prehistoric male adult whose skull showed artificial occipital flattening. Using the classification system developed at the 1927 Pecos conference—which they had attended—the Cosgroves were the first to record for Gila Cliff Dwellings two components, or distinct occupations, one of which was very early. This observation was only recognized in the adjoining caves years later and independently of their work. In addition to the skeleton, they recovered artifacts that they identified as of Pueblo or Basketmaker origin, including (Pueblo origin) broken reed arrows, a miniature ceremonial bow, feather cloth, "gaming sticks," sherds of Tularosa fillet-rim and Tularosa Black-on-white and (Basketmaker origin) a wood dart foreshaft. A shell gorget, reed cigarettes, and vegetal remains were of ambiguous origin. Collotypes of some of these objects were included in the analysis, which was finally published in 1947.

Better known for their excavation of Swarts Ruin in the Mimbres Valley, [30] the Cosgroves subsumed the cave surveys into their 1932 report on the Swarts site by drawing the boundaries of the Mimbres culture, at that time still viewed as a variant of the general pueblo culture, to include in the north all of the West Fork and Middle Fork of the Gila River. These boundaries notably excluded the upper San Francisco River and the Tularosa River—the area explored by Hough during the Gates-Museum expedition. In the final report of the cave survey, they did record the presence of Tularosa ceramics at Cave 2 on the West Fork (Cave 6) and at five other cave sites between the confluence of Sapillo Creek with the Gila and the cliff dwellings along the Middle Fork, artifacts "indicating more northerly contacts."

Although neither Caves of the Upper Gila nor Swarts Ruin contains a description of the TJ pueblo site, the Cosgroves had apparently seen the ruin: they recommended in 1934 that it be studied by the National Resources Board, [31] a new organization that had been created by executive order to study resources, including needs for state and national parks.

The same year that the Cosgroves were climbing into caves on the upper Gila, the goal of a general cultural history of the Southwest was complicated at the third Pecos conference when the relevance of Pecos classification to locales below the Mogollon rim was challenged. Two years later, at a conference held at the Gila Pueblo archeological foundation in Globe, Arizona, a second classification framework was developed for a southern prehistoric culture (Hohokam). In 1934, yet a third culture (Mogollon) was recognized for southwestern New Mexico by H. S. Gladwin, founder of the Gila Pueblo, and formally described in 1936 by Emil Haury, whose archeological excavations at Mogollon Village and the Harris site had been sponsored by Gila Pueblo.

Already dissatisfied with the Pecos classification sequence, Gladwin suggested in 1934 a new and universal system of classification, using a genealogical tree as the organizing metaphor. [32] The roots of this tree were the principal recognized Southwestern cultures, at that time Hohokam, Caddoan (subsequently labelled Mogollon), Basketmaker (subsequently labelled Anasazi), and Yuman (subsequently labelled Patayan and later Hakataya). The stems were regional variants of the roots (San Juan stem of the Basketmaker root, for example). The branches were still smaller geographical variants within stems (Chaco branch of the San Juan stem of the Basketmaker root). Each branch could further be divided into phases that represented distinct developmental stages. Regarding the Anasazi, the Pecos classification sequence could still be used for that level of division, but for branches of other roots a plethora of new names was required to identify specific phases that were ultimately recognized by finely grouped traits of material culture. The four roots are still used as a conceptual framework to classify the prehistory of the Southwest.

The Gladwinian "genetic-chronologic" system of classification and the conceptual fragmentation of the previously "general" pueblo culture had three long-term effects on the archeology of the upper Gila. First, no one knew how far the culture root might extend geographically. As a result, research in southwestern New Mexico shifted from relatively well-excavated sites on the Mimbres drainage to the headwaters of the San Francisco River and to sites farther west in Arizona, new country suggested by Gila Pueblo. Although Hough had noted many sites 30 years earlier around Reserve, with one brief exception they were still unexcavated in the late 1930s. Chief among Hough's successors in the area were Paul Martin and his colleagues, whose work was sponsored by Chicago Natural History Museum, and later Edward Danson, whose survey of west-central New Mexico and eastern Arizona was sponsored by the Peabody Museum. After Haury published in 1936 a phase sequence for the Mogollon, [33] no additional research formally occurred in the Mimbres area, including the forks of the Gila, until salvage operations at Gila Cliff Dwellings in 1963.

Second, as cultural boundaries were researched, the Mogollon root began to be parsed into more and more branches based on increasingly fine artifactual distinctions. For example, in 1947, Haury reported three branches (Mimbres, Forestdale, and San Simon); by 1955 Joe Ben Wheat noted six branches and possibly two additional ones (Mimbres, Pine Lawn—possibly a northern Mimbres subset—Forestdale, San Simon, Black River, Cibola, Jornada, and possibly another as yet un-named branch in Chihuahua, Mexico). As a result, discussion of the "Mogollon problem" became increasingly burdened with taxonomies and the lists of material traits needed to distinguish the various branches, all of which had largely separate sequences of phases that required more lists as well.

The third effect was more subtle. With attention focused on new areas, there was a tendency to overlook or not to perceive complexities, variations, or anomalies within already described branches, some of which had been described on the basis of excavation at a single site. Given the very limited amount of archeological work on the Gila River and the initial concentration of research in the Mimbres Valley, the effects of this normative tendency were pronounced during the first years of Park Service management at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument.

Park Service: Gordon, Reed, And King

In March 1935, almost two years after the official transfer of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument from Forest Service to Park Service management, "Boss" Pinkley, superintendent of Southwestern Monuments, was finally able to send someone to look over the new acquisition. G. H. Gordon, an assistant engineer, was guided by Leslie Fleming of the Gila Hot Springs Ranch on an 18-mile horseback ride to the cliff dwellings. There Gordon made a sketch plan of the cave-sheltered ruins. He also gathered a small surface collection of fragmentary artifacts and later reported some evidence of digging. Within the previous month, reportedly, amateur diggers from a nearby CCC camp had visited the ruins, and three or so years earlier "a party visited the dwellings and did more or less digging and...found a bead necklace, after they had pushed over a wall." Despite these ransackings, Gordon suggested that the floor fill might still contain a great deal of prehistoric material, and he felt the architecture was well made and worthy of recognition. Among other recommendations, he suggested the ruins be included in the plan for ruins stabilization. During his stay he visited two extensive "Pueblo III" pithouse sites. Unfortunately, he did not specify their location other than as "in this locality."

Two years later, Erik Reed, an assistant archeologist for the regional office in Santa Fe, accompanied a team of Park Service investigators to inspect the Gila Primitive Area and to assess the entire area's potential—600,000 or so acres—for national park status. With the exception of Gila Cliff Dwellings, Reed reported that none of the other numerous archeological sites was of popular appeal and that they hardly constituted a "primary reason for the establishment of a National Park" although they would be features of interest in a park, especially since the area had never been extensively studied. [34] An allusion to the TJ site and the passing observation that only the cliff dwellings were of any importance underscores how much study remained to be done. At the cliff dwellings themselves, the investigators debunked the rumor of a recent collapse of an archway within the walls, using as a base for comparison photographs of the site that had been published in Hough's 1907 survey.

In 1939, Dale S. King, a Park Service naturalist working out of the Southwestern National Monument office in Casa Grande, Arizona, visited Gila Cliff Dwellings, where he took a dendro-chronological sample from one of the beams. Emil Haury, who was then working at the University of Arizona, dated the sample as A.D. 1286, providing the first scientifically derived date specific to the site. Two years later, archeologists from Gila Pueblo took additional samples, but these were not analyzed until the 1960s. [35]

Steen

With the abandonment around 1940 of a proposal to elevate the Gila Primitive Area to national park status, the official assessment of Gila Cliff Dwellings declined, as well. In 1941, the superintendent of Southwestern Monuments concurred with the regional director that those ruins, despite their charm, be regarded as only a reserve monument and that visitation be discouraged. The cliff dwellings had, however, been placed on the general stabilization plan as Gordon had suggested in 1935, and a "non-recurring allotment" of $390 was scheduled for fiscal year 1942, an amount that compares favorably with the $200 recommended for Aztec National Monument, for example, or the $240 for Chaco Canyon National Monument in 1938.

In July 1942, stabilization finally began at Gila Cliff Dwellings when Charlie Steen drove to the Gila Hot Springs Ranch in a "Chevy truck with a panel body and a granny gear." A junior- grade archeologist, Steen had started working for "Boss" Pinkley eight years earlier as a custodian at Tonto National Monument in Arizona and later at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. He spent nearly five days at the cliff ruins, with a hired laborer, taking measurements for a ground plan and core samples from the beams, shooting photographs, reinforcing with dry masonry the foundations of several walls in Caves 2 and 3, cleaning the site, and building a trail from the small stream in the canyon to the cave-sheltered archeological site. Steen also dug two trenches to recover sherds—one along the south wall of Room 10 and another on a north-south axis in the middle of Room 17. With the single exception of a Mesa Verde black-and-white sherd, according to Steen's report, all the other pieces of pottery were Tularosa wares.

Several years later, at the request of "Doc" Campbell, the monument's custodian, Steen and Erik Reed both provided the custodian with brief overviews of upper Gila prehistory. Relying heavily on Haury's 1936 description of the Harris site, Steen repeated the supposition that the Mimbres culture after A.D. 900 was an amalgam of the Anasazi, Hohokam, and Mogollon. [36] The cliff dwellings, Steen proposed, had been built by these Mimbrenos around A.D. 1000, deserted and then possibly but only briefly reoccupied by Anasazi around A.D. 1300. The latter supposition was based on ceramics—presumably the Mesa Verde Black-and-white sherd [37] — and some signs of rebuilding. [38] Undoubtedly, he was aware of King's dendrochronological sample, which postdated the general Mimbres abandonment mentioned in his overview. [39] In addition, the Mimbres component at Gila Cliff Dwellings was partly inferred from sherds although by Steen's own admission they were all Tularosa ware [40] —ceramic types then well-known as products from the upper San Francisco valleys and not of the Mimbres Valley. Part of the problem, of course, was that in 1949 the boundaries of the Mimbres branch were still drawn around the headwaters of the San Francisco drainage. Although material cultures in the two areas were known to differ, the distinction was obscured by limitations of taxonomy. Mimbres construction was invoked, with A.D. 1000 as the generally accepted date for the shift from pithouse to surface architecture, and the true nature of archeological components at Gila Cliff Dwellings would be obscured for another 15 years.

Reed's overview was more cautious. [41] Drawing from the 1937 report of his visit to the upper Gila, he noted the meager amount of archeological reconnaissance and the virtual absence of excavation in the area, and mentioned without comment prevalent pottery types—Mimbres Black-on-white, Tularosa, other Black-on-white types, and Gila Polychrome. Deeper into the overview, Reed distinguished Mimbres from Tularosa cultures based on ceramic firing technique, with the latter showing greater Anasazi influence. Generally without mentioning specific sites, he also described architectural styles, which included small cliff ruins in little caves and moderate-sized open pueblo ruins. The open sites he recognized as "apparently that of the Mimbres." The cave sites he associated with Tularosa, citing the A.D. 1286 date from Gila Cliff Dwellings as the latest known for that people.

Obviously familiar with the then recently published results of the Cosgroves' cave survey, he mentioned the presence on the upper Gila of "Basketmaker" sites, a term he subsequently interpolated as San Pedro phase of the Cochise culture that was and is still believed to have engendered the Mogollon sequence, and he substantiated this phase designation with a list of material culture traits. In the same way, he had associated the "Pueblo" artifactual assembledges with "the Tularosa phase." That San Pedro phase ("Basketmaker") and Tularosa phase ("Pueblo") components had been documented in a cave adjacent to the cliff dwellings and part of the national monument is a fact that he did not mention. Possibly he was not aware that West Fork Cave No.2 lay in the monument—the Cosgroves had not been, after all.

Both written about the same time, Reed's cautious overview differed in style, scope, and conclusion from that of Steen, who for one was prepared to draw some conjectures about the initial history of the cliff dwellings. The cultural affiliation of the cliff dwellers was not resolved until after the ruin was excavated in 1963 and after Mogollon taxonomy had been further refined. The weight given the question of identity, however, seems to have overwhelmed Reed's early—perhaps offhanded but at least initially useful—distinction between open sites and cave sites. After some reconnaissance in 1955, Park Service archeologists were inclined to use Mimbres phase ceramics from open sites to support inferences about a dominant Mimbres phase component at Gila Cliff Dwellings. After additional tree ring analyses and excavation brought into resolution a single Tularosa phase construction and occupation of the cliff architecture, there has been an occasional tendency for inferences to flow the other way. In 1981, for example, a report developed to aid the evaluation and identification of the state's prehistoric resources identified the entire monument as Tularosa phase. [42] Most recently, in a Park Service study for suitable commemoration of the Mimbres Culture, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument was identified as "a Tularosa site, with no Mimbres or earlier material represented." [43]

Because allocations to the National Park Service declined during the Second World War, Gila Cliff Dwellings was not officially revisited until 1948, when Steen reported structural damage. Seven years passed, however, before funds were allocated for repairs.

Richert, Campbell, And Vivian

In July 1955, Roland Richert, who assisted Gordon Vivian on the Mobile Stabilization Unit based at the Chaco Canyon Field Station, came to Gila Cliff Dwellings for three weeks to stabilize the ruins with the help of five Navajo laborers. On Sundays, while his crew rested, Richert scouted the national monument and its vicinity, collecting grab samples from six different sites, which he later sent to Emil Haury for identification.

From the cliff dwellings, he picked up 15 decorated sherds, which were eventually sorted in the following categories:

Bold Face B/W 20% Three Circle B/W 13% Tularosa B/W 53% Reserve 7% Heshotauthla Polychrome 7%

Based on these ceramics and the architecture of the cliff dwellings, Richert stated in his stabilization report that the cliff dwellings exhibited the climax of the Mimbres phase of the Mogollon culture and modified Steen's earlier inferences, which he had read, by pushing the initial dates back to A.D. 900 and the last dates to perhaps as late as A.D. 1400. Richert acknowledged the small size of his sampling but felt that additional "representative collections" from several nearby surface ruins did substantiate a Classic Mimbres occupation of the area and "a later influence from the north, possibly Tularosan in character." [44]

|

| The TJ Ruin lies on a bluff overlooking the Gila River, near the confluence of the West and the East forks. |

One of the nearby surface ruins from which Richert had also taken a sherd sampling was the TJ Ruin, and based on these ceramics the site was identified as Mimbres "into and beyond the classic period." [45] In other words, the multi-component nature of the site was finally recognized, and appreciation of the ruin began to rise. When E. B. Danson visited the area for the first time in 1962, he expressed such interest in the anticipated excavation of the TJ site that excavation at Gila Cliff Dwellings was almost an afterthought. [46]

Not long after Richert returned to Chaco Canyon, his supervisor, Gordon Vivian, took personal leave in order to visit the Gila Cliff Dwellings, where he followed "Doc" Campbell up and down enough hills until he had a sense of the archeological wealth of the area—much as Bandelier had done 70 years earlier. The urgency of Vivian's and Richert's interest in the local archeology stemmed, of course, from the 1955 MISSION 66 prospectus from the regional office, which arrived at Campbell's while Richert was supervising stabilization of the ruins. In view of potential improvements to access into the Gila forks area, the prospectus proposed abandoning Gila Cliff Dwellings (i.e., donation to the state of New Mexico) and acquiring a site more representative of the "prehistoric culture of Southwestern New Mexico." Upon his return, Vivian cautioned the general superintendent of Southwestern National Monuments that the area should be thoroughly studied before abandoning it. [47] His memorandum supported a previous letter by Campbell, the custodian, who was meanwhile drawing maps.

One of Campbell's maps, first made for Richert during his stabilization work, was a sketch of Cliff Dweller Canyon. The map noted nine other sites within the national monument in addition to the cliff dwellings themselves and another 13 sites still in the canyon but beyond the monument boundaries. Another map located 13 other sites, including the TJ Ruin and the West Fork Ruin, along the West Fork and within a mile and a half of the monument. Although these surveys were informal, the importance of many of the sites was soon corroborated by Dale King, who had been sent from the regional office in response to Campbell's and Vivian's letters, and within a year by then Regional Archeologist Steen. Combined with Richert's samplings, Vivian's reconnaissance, and the solicited opinions of such prominent authorities as Danson, the Campbell's maps helped to bring informed attention to a sequence of local prehistory that appeared to cover nearly 2,000 years, a span apparently greater than any area managed by the National Park Service.

In 1956, when Vivian wrote an archeological resume of the Gila forks locale, he classified the cliff dwellings as a Classic Mimbres phase site. Coupling this classification with a line from Erik Reed's 1949 overview about zoomorphic pottery designs completed the normative tendency to extrapolate "from the Mimbres Valley to fill in the enormous lacunae in knowledge about the Upper Gila." [48]

Vivian's classification was based on Richert's sherd samplings, of course, and elsewhere he acknowledged possible late influence at the cliff dwellings by the Tularosa culture, an affiliation based on the ceramics, a suggestion by Danson, and an unexplained reference to style in architectural rebuilding. In 1955, most of the country along the San Francisco River and the Tularosa River was about to be parsed from the Mimbres branch, which would establish Reserve and Tularosa phases as distinctly non-Mimbres in the Mogollon taxonomy. This division was intimated in Joe Ben Wheat's general synthesis of the Mogollon culture, published the same year [49] and stated flatly by Danson two years later. [50]

The purpose of Vivian's resume was not, however, to clarify obscurities of territory and potential subdivisions of culture. He was arguing instead for an expansion of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument in order to include "a unique and valuable sequence of Mimbres culture from beginning to end." The operative word, so to speak, was sequence. He focused on sites representative of each phase of the Mimbres branch, marshaling authoritative corroborating support and adding as a fillip to his argument the threat of inevitable despoliation at the Heart Bar (TJ) Ruin, the last best Mimbres ruin. Apparently for the sake of simplicity, Vivian skipped over the issue of Tularosa influence in his resume, eliding the word even from his quotation of Reed. He closed his sequence of phases with two scenarios: a proposed late migration into the Gila forks by Salado people, possibly from the more northern Pinedale-Cibola area; and a declining but continued occupation by Mimbres people under Salado influence, an idea that he tentatively endorsed with the A.D. 1286 date for the cliff dwellings and with late pottery from the TJ site. The significance of this dendrochronological date had been shifted from being the last Tularosa date to an early Salado date.

The resume and a new consensus about the importance of archeology around Gila forks led ultimately to the expansion of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument in 1962.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

gicl/adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 23-Apr-2001