|

Gila Cliff Dwellings

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter III:

HISTORY OF TENURE AND DEVELOPMENT 1955 TO 1991

In the wake of the revised MISSION 66 prospectus, archeologists Steen and Vivian respectively drafted a formal report and an archeological resume that outlined the new importance of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument and the nearby ruins. [1] Steen concluded with a proposal that between 1,000 and 1,200 acres be added to the monument, in a narrow strip descending the river as far as and including the TJ Ruin. To Vivian's resume was attached a map of the newly proposed boundaries for the monument. All of this land was administered either by the Gila National Forest or the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, which had purchased the Heart Bar Ranch in 1951 as part of a long-term project to reintroduce elk into the area.

In order to negotiate new boundaries for the monument that would be satisfactory to all agencies concerned, it was agreed to hold a joint meeting at the site in September 1956. Colonel Ely attended this meeting, as well. He reported that the Forest Service had no objections to the Park Service consolidating its holdings. [2] Actually, however, forest staff had already expressed opposition to including West Fork and East Fork trails within the extended boundaries, citing their reluctance to hamper access into the wilderness for recreation and hunting. [3] The game department shared this concern about access.

Eventually a compromise between agencies was reached. This compromise entailed dividing an expanded monument into two tracts: 320 adjacent acres of wilderness would be added to the 160 originally set aside as Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, and a separate tract of 140 acres at the TJ Ruin would be transferred to the Park Service, as well.

The proposed division appeared to accommodate everyone. The TJ tract, it seemed, was large enough to hold the proposed headquarters, parking, service areas, and exhibits for the monument; and most of the land in the river canyon between the TJ site and the cliff dwellings remained with the Forest Service and the game department. In addition, Homer Pickens, the director of the game department, informally agreed with the Forest Service to trade 35 acres of the Heart Bar Ranch in exchange for forest and Bureau of Land Management lands elsewhere in New Mexico. This Heart Bar site could then be used as a headquarters for the Wilderness District of the Gila National Forest. [4]

A minor glitch soon appeared, however. When the Park Service had the TJ area surveyed in 1957, the boundary corners did not match the original survey, a misalignment that delayed progress on the necessary withdrawals until after Homer Pickens retired. [5] In February 1958, a survey crew from the Bureau of Land Management re-set some missing section corners near Gila Cliff Dwellings and the TJ site; and five months later, when the West Fork was sufficiently low to cross in vehicles, representatives of the Park Service, the Forest Service, and the game department met again at the TJ site. [6]

Meanwhile, a new problem had arisen. A few days before the meeting, Sam Servis, from the supervisor's office of the Gila National Forest, and Gordon Hammon, from the regional office of the Forest Service, toured the TJ site together and agreed that the Park Service was asking for too much land. [7] If the much discussed Copperas road were built, a right-of-way might have to be established near the ruin. And recreational facilities as well as a forest ranger station might also have to be constructed. Servis and Hammon believed that the expanded albeit divided monument would still control the best sites for those developments.

In part, behind this new and more restrictive line was concern that the new director of New Mexico Game and Fish would not abide by the informal understanding to exchange the Heart Bar headquarters area for land elsewhere. [8] At the interagency meeting on July 8, the Park Service representatives could not agree to a reduced TJ tract, however, and the meeting adjourned inconclusively. [9]

Finally, in December 1958, the unraveling ends of the earlier understanding were gathered into a new compromise. Fred Kennedy, the regional forester, revealed at yet another interagency meeting that he was planning to proceed with the withdrawal of the land adjacent to the TJ Ruin for his own agency's administrative purposes. At that point, Harthon Bill, the assistant regional director for the Park Service, suggested that the administrative site might be used jointly. [10] Subsequently, Bill's inspiration was accepted by both agencies. It was justified as an opportunity to avoid duplication of services, to reduce construction and operating costs, and to model cooperative relations.

In the final agreement, 53 acres around the TJ Ruin and 320 acres adjacent to the original 1907 withdrawal were to be added to Gila Cliff Dwelling National Monument. An easement 300 feet wide was also to be reserved along the West Fork for public travel, resolving the long-standing concern about access through the narrow canyon to the wilderness.

To legally revise the monument boundaries required either an act of Congress or a proclamation of the president, using the authority provided by the 1906 Antiquities Act. On April 17, 1962, Presidential Proclamation No. 3467 was signed. Its publication three days later in the Federal Register consummated the transfer of land. [11] For the sake of simplicity, this proclamation additionally transferred to the Park Service title to the original 160 acres. When the land had been reserved in 1907, it had been endowed with a dual status as national monument and as a property of the Gila National Forest. Curiously, the executive order in 1933 had not revoked the dual status.

Also, shortly before President John F. Kennedy signed the document expanding the monument, the Forest Service withdrew—by means of Public Land Order 2655—107 acres adjacent to the proposed TJ unit of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. [12] The interagency understanding to use this withdrawal as a joint administrative site was subsequently realized through a cooperative agreement that was formalized on July 22, 1964. [13]

Clinton B. Anderson Memorial Highway

The expansion of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument was negotiated in a quiet collegial manner between federal agencies and with participation by the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. The road from Sapillo Creek to the monument, on the other hand, was the clamorous product of local citizens and their community organizations lobbying with letters, telegrams, petitions, resolutions, editorials, and caravans. Because the Copperas road and development at the monument were linked, progress on both projects advanced in tandem but with a jarring cadence.

Not long after the second MISSION 66 prospectus had been produced in November 1955, advocates for an improved road to the forks of the Gila sought support from the New Mexico congressional delegation, as well as from the offices of Southwestern National Monuments and of the Gila National Forest. [14] Chancie Snyder, in particular, spoke with Russell Rea, the local forest supervisor, inquiring about potential help and noting that representatives of the Park Service were very interested in having a road built. Rea's cautious response stood for the next four years: "[the Forest Service] would be glad to see a road built into the area but [was] not in any position to help on such a project because we had no funds or personnel available." [15]

A letter in January 1956, by "Doc" Campbell to Dennis Chavez, New Mexico's senior senator, took a different and more aggressive tack. Noting that "Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, on the Upper Gila, has been the stepchild of the U.S. Government for 49 years," he entreated the senator as a person of national renown to champion the development of the area in the interests of archeological protection, tourist dollars, fire control, and recreational use. [16] Routed by Chavez to the director of the Park Service, Campbell's letter elicited a cautious reply that further study was needed before committing to a development program at the monument. [17]

Based on different sources and repeated with different sympathies, Snyder's version of the Park Service interest in the Copperas road, Campbell's darker implications, and the tepid official response to Senator Chavez created a useful kind of confusion. As its consequence, advocates for the road could tailor their arguments to any audience and corroborate their points with appropriate documents and anecdotes. Speaking, it seemed, not only in the best interests of the community but in the best interests of the Park Service and even the Forest Service, these advocates enlisted the kind of congressional interest in the road and the monument proposals that nudged them both towards development.

In December 1957, Senator Chavez again wrote the Park Service, indicating that he was "hopeful that either one or both of your agencies will try and work out ways and means of making this very essential road improvement." [18] This letter was based on presumption and the kind of circular logic that had advanced the cause of development: (1) the road was important in order for the monument to be developed, and (2) the monument should be developed because a road was going to be built. The presumption, of course, was that the Park Service wanted to implement the second MISSION 66 proposal, which was still only a tentative plan, after all. In fact, in 1957, the Region III Office was still uncommitted to development at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. For one thing, it was still negotiating boundaries with the Forest Service.

The presumption of the letter from Senator Chavez, an independent inquiry from Senator Anderson, and consequent memoranda about strong congressional interest [19] in the still remote monument encouraged officials of the Park Service to accelerate their planning process. [20] In July 1958, Conrad Wirth finally approved the revised MISSION 66 prospectus. [21] The cautious—hypothetical, even—support for the Copperas road that Russell Rea acknowledged to Chancie Snyder was enhanced more or less in the same way as the issue floated through the channels of the Forest Service.

Although endorsements for the Copperas road from the Forest Service and the Park Service were important, a more immediate problem in 1956 had been the issue of a road in the Gila Primitive Area. The residents on the Gila forks had built a road based on their rights of ingress and egress, but a public road to the cliff dwellings had no legal basis, according to the chief forester of the Forest Service. [22] In fact, he added, it would be inappropriate for his agency "to construct or to participate in any way in the construction or promotion of a road in a Wilderness or Primitive area."

Colonel Ely took immediate issue with the chief forester's pronouncement, referring to the 1952 recommendations of the James Committee, which had endorsed the extension of a road corridor through the primitive area as far as Gila Cliff Dwellings. In a series of irate letters and editorials, Ely accused the Forest Service of reneging on a compromise that the Washington office had not approved. [23] The colonel's irritation appeared to mystify staff at the regional office of the Forest Service, [24] who again referred to his undeniable ingress-egress rights as a resident at Gila Hot Springs; nevertheless, Ely's letters drew the weighty attention of Senator Clinton Anderson.

After a few months of correspondence with Anderson, who had personally helped to negotiate the earlier boundary compromise for the Gila Wilderness, the regional office of the Forest Service recommended the formal extension of the corridor, citing the continuing controversy over the road into the Gila Primitive Area and the recommendations of the James Committee. [25] The extension process, however, entailed a petition, a notice of intent to modify the primitive area, and a six-month waiting period. Unhappy about the processual delay, Ely finally explained in a September editorial the source of all his irritation—unless a public road were quickly designated through a corridor in the primitive area, Ely feared that federal funds could not be appropriated for future improvement. [26] In spite of the colonel's displeasure, the full procedure for deleting land from a primitive area was observed, and a corridor to Gila Cliff Dwelling National Monument was not formally established until July 15, 1957.

Once the corridor had been clearly established, efforts of the local road lobby were applied towards acquiring federal appropriations. Coordinating these efforts for the Silver City-Grant County Chamber of Commerce was Francis Parsons, who was president of the Grant County Archaeological Society and who took a special interest in the monument, having helped "Doc" Campbell identify the TJ Ruin as a Mimbres site and having guided Lambert to the cliff dwellings a year earlier. [27] In December 1957, at a public hearing in Albuquerque, New Mexico, [28] Parsons presented the first formal request for support to a group of U.S. senators. [29] Asking that they help make possible "the greater Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument" in order to promote tourism at a time when low prices for metals were dragging down the local economy, Parsons also cited the potential benefits that a road would bring the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, the Forest Service, and recreationists in general.

Afterwards, Leslie Arnberger, the regional chief of Park System Planning, reported that very little official interest in the road proposal had been evidenced, but he noted with some prescience that strong political pressure could change this prospect. [30] Indeed, within five months, Senator Chavez sent a representative from his Committee on Public Works to meet with officials of the New Mexico Highway Department, the Bureau of Public Roads, the Forest Service, the National Park Service, and others, including Francis Parsons, who again made the case for a road from Sapillo Creek to the forks of the Gila River. [31] Reporting on this meeting, Harthon Bill, the assistant regional director of the Park Service, noted that all parties said they were favorably inclined towards construction of the road but that for a variety of reasons none had the funds to do it: the Forest Service was already maintaining a 1,000 miles of gravel road with insufficient funds, the Grant County Road Department had given other roads priority, and his own agency could only appropriate funds for work within the boundaries of the monument.

Bill also reported that "there was an obvious effort to place responsibility for sponsoring the construction of the road on either the U.S.F.S. or N.P.S." [32] Believing that an acquiescence to this responsibility would entail financial obligation as well, he advised a cautious economy. This caution was manifested soon afterwards in the final version of the MISSION 66 prospectus for Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument: development at the monument was specifically contingent on the construction of an approach road by another agency. [33]

As the funding dialogue moved into the offices of federal agencies, Parsons continued to draw attention to the road issue by organizing annual jeep caravans to Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Starting in 1958, the caravans attracted increasing numbers of visitors to the monument and a lot of publicity. In 1960, for example, the Albuquerque Journal reported that on the third annual caravan 260 people had driven in a column of army transport trucks, jeeps, and pick-up trucks "through one of the scenic southwestern wonderlands," and the article highlighted not only the isolated monument but other attractions of the wilderness. [34]

Eventually, funding for improvements to the Copperas road was secured through its inclusion in the state's system of secondary roads. Once the jeep track road was sketched onto the inventory, Senators Chavez, Anderson, and other interested legislators secured for its construction $1,000,000 of Federal Lands Highway Funds, [35] by means of the Federal Highway Act of 1960. The next year, the state of New Mexico allocated another $200,000 towards the project. [36] All of these funds were applied for construction from Sapillo Creek to the monument. In addition, the Forest Service agreed to spend $100,000 improving the road from the forest boundary north of Pinos Altos to the Sapillo crossing. [37]

The Park Service did not contribute toward the road. In fact, even after the federal appropriations had been made, Hillory Tolson, the acting director, reported to the Bureau of Public Roads "that the objective of reaching Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument does not appear to rank of sufficient importance in comparison with the costs involved." [38] Granted, Tolson was attempting to parry a renewed request to help pay for this road, which was still underfunded. But this financial sidestep revealed a larger discontinuity: road advocates were now justifying a million-dollar appropriation in the name of a monument that officials of the Park Service did not think merited the expense.

More bluntly, the regional engineer for the Bureau of Public Roads observed at the time that none of the federal or state agencies involved was very interested in the road and that pressure for the road was almost entirely from the area around Silver City. [39] For a long time, it had been easy to underestimate the efficacy of that pressure. Construction on the Copperas road began in 1961 and continued in three phases, reaching the monument in early 1967.

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument 1955-1963

Meanwhile, as negotiations flowed between state and federal agencies, senators, and citizens interested in the monument's expansion and the construction of an approach road, the prehistoric site remained an official backwater. After visiting the site for the first time in 1958, Harthon Bill reported that "it is probably the most difficult National Monument in the continental United States for people to reach." [40] Observing that its reserve status had stemmed from this inaccessibility, he recommended that management of the monument for the time being concentrate only on protecting the cliff dwellings.

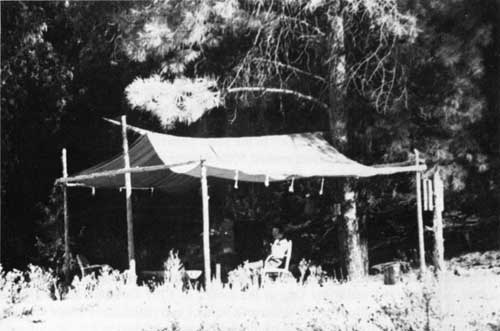

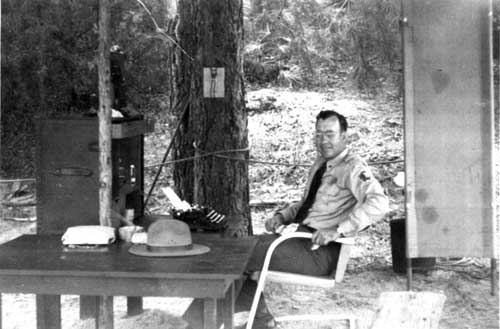

Three years earlier, for that very purpose, "Doc" Campbell had been hired as a seasonal ranger, and for the next eight summers someone in uniform greeted visitors and monitored the ruins daily. As recommended in the second MISSION 66 prospectus, Campbell was provided with some "office facilities," which in this case comprised a typewriter and a filing cabinet. On his own initiative and with his own money, Campbell additionally established a modest visitor contact station at the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon, using a tent-fly, a telephone, and an army field desk. In 1990, Campbell recalled his improvisations:

Well, after the Forest Service phone line—the magneto line—went through the monument, I took a field phone and hung it on a tree—a spike in the tree—so we had communications up there. And then we put up a fly. We made tables and bought a field desk...And then we got an appropriation—I think I got another $150—and we built some benches and put them along the trail. Built nine benches and a picnic table from the mouth of the cliff dwellings canyon up to the cliff dwellings, clear up to the monument where people could stop and rest and enjoy the scenery.

Also, the Forest Service had put down by Scorpion Corrals an outhouse. We took a Ford tractor and hauled that outhouse up to where people were stopping, and put it in. We put it on Forest Service land just below there. Anyhow, I didn't ask anybody. I just did it and then cleared out to where they couldn't go to the bushes...So that helped out with sanitation around there. And that's the way things were done. [41]

|

| The first contact station at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument was assembled by Custodian "Doc" Campbell, using a tent-fly, an army field desk, a typewriter, and a telephone that he hung from a no. 9 magneto line that belonged to the Forest Service. The lower photograph shows Campbell at his office. |

From his tent-fly station, Campbell dispensed information to visitors who then drove or waded across the river to visit the prehistoric site. In the years between 1955 and 1962, the number of these visitors increased moderately from around 500 a year to approximately 1,500. [42] In addition to greeting people, Campbell continued to maintain the canyon trail and to report damage to the ruins. In late 1962, he even stabilized a small portion of the site at the request of the regional archeologist. [43]

In the summer of 1962, as construction of the improved road advanced towards the Gila forks, Campbell declined the seasonal position to prepare his business for the expected surge of tourists. He still remained the nominal custodian, however. In his stead, a school teacher was hired for the summer, who worked under the tarp at the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon and camped nearby in a wall tent. The discovery by this man's wife of two rattlesnakes inside the tent on the same day is still cited locally as a benchmark of dirt-floored rusticity.

Development Planning

In mid-1962, prompted by the recent expansion of the monument and the imminent completion of the Copperas road as far as the Gila River, work began on developing a package master plan for the monument. The initial MISSION 66 prospectus had recommended that "a modest public building" be constructed at the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon regardless of whether the area became a state monument or remained with the Park Service. [44] The revised prospectus reported that the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon was prone to flooding, and it recommended that a slightly more elaborate but still modest building be located within walking distance of the TJ Ruin. [45] This building, it was suggested, "should house the permanent superintendent's office, an attractive lobby, possibly with room for a continuous recorder projector orientation presentation, one ample display room, a workroom with a small dark room in one corner, and a storeroom." [46]

Following the proposal to jointly occupy the TJ administrative site, Fred Kennedy, the regional forester, drafted a letter to his counterpart in the Park Service. Kennedy outlined some planning specifics, including recommendations that the architectural design and building specifications be done by the Park Service as the predominant user. His own agency would review the plans, of course. [47] He also suggested that the administrative building have a lobby arranged so that both agencies could install exhibits. Until a cooperative agreement was signed in July 1964, Kennedy's letter served as a basis of understanding between the two agencies, and—along with the MISSION 66 prospecta—it guided the process of developing a master plan.

During the planning process, the most debated topic was the location of the visitor center. At an interagency meeting in July 1962, Volney J. Westley, a landscape architect with the Region III office the Park Service, recommended that the center be located east of Cliff Dweller Canyon near the tent-fly headquarters, observing that most drivers would pass up the TJ road spur and continue directly to the cliff dwellings. [48] Housing and utility buildings could still be located on the joint administrative site near the TJ Ruin, he added. Complicating this proposal, however, was the fact that the site he specified for the visitor center was Forest Service land, and its development would require a special-use permit or even a joint agreement like that proposed for the TJ administrative area.

Given the limited amount of space at the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon and the hazard of windfall from a grove of large cottonwood trees, Sam Servis, then assistant supervisor of the Gila National Forest, also recommended at the same meeting that a camping area not be developed there but instead near Scorpion Corral, a location on Forest Service land that might also mitigate a potential problem of overcrowded parking at the monument.

A year later, the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon had again been abandoned as a location for the visitor center because of flood danger, and three other sites had been eliminated for the same reason as well—Scorpion Corral, Doc's Cienega, and Pine Flat. [49] Only the TJ area and a site called Pine Terrace appeared to be safe from floods, and the latter site was not appropriately located.

In June, however, during a meeting between agencies at the Heart Bar headquarters, yet another location for the visitor center was proposed to the director of the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. [50]

The proposal was complicated. If the Forest Service could trade grazing rights in northern New Mexico for title to some of the Heart Bar land, then it would enter into a cooperative agreement with the Park Service, permitting the latter agency to locate a visitor center/administration building near the Heart Bar headquarters. Included in this building would be space sufficient for a district headquarters for the Gila National Forest and at least one office for the game department. All three agencies would share exhibit space in the lobby. In addition, all utility buildings and residences could be located on the TJ administrative site or on other nearby land that was managed by the Forest Service.

This proposal appeared to solve a lot of problems for the Park Service. The location was clear of the flood plain, the main approach road to the monument would pass close by, room for parking was ample, good drinking water was easily available, and there were pleasant views of the TJ area. The proposal foundered, however, on the issue of property values, [51] the reluctance of the local game commissioner, [52] and the need to obligate money before the start of the new fiscal year. [53]

As a consequence, the original TJ administrative withdrawal area was again designated the best location for the visitor center—by default. The long dialogue between agencies was not in vain, however, having shaped the final plan for development in several ways. One improvement, for example, was the planned addition of a contact station at the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon, an addition that addressed earlier concerns about drivers who might bypass the TJ road spur. Another improvement carried over from the failed Heart Bar proposal was the idea that headquarters for the Wilderness District of the Gila National Forest be included in the visitor center. A headquarters was a more substantial need than had been anticipated in 1960, when only temporary quarters for a crew of four to six men, a utility building, and corrals were proposed. In short, the final Master Plan for Gila Cliff National Monument evolved as a product of site constraints, changing perceptions on the part of both agencies about their own needs, and a lot of very cooperative and creative dialogue.

The 1964 Cooperative Agreement essentially divided responsibility for developing specific projects specified by the master plan. The agreement permitted the Park Service to develop a contact station on Gila Forest land near Cliff Dweller Canyon, and it authorized a joint headquarters at the TJ site, which both agencies would finance together and in equal amounts. Specifically, the Park Service would pay for the visitor center/administrative building and carry that structure on its property records; the Forest Service would pay for landscaping, roads, and bridges and carry those improvements on its property records. Each agency would carry on its own property records any other buildings that it had constructed, including residences, barns, corrals, etc. [54]

Although first proposed as a compromise between competing needs for the limited space on the forks of the Gila, the joint occupation of the TJ administrative site did indeed save money for each agency, as well. In mid-1958, before joint occupation had been proposed, the Park Service tentatively approved the expenditure of $423,700 for capital improvements at the monument. [55] Ten years later, the agency had only spent $350,000 to complete its share of development at the administrative site, which included two residences. In a similar way, initial projections for five permanent staff were reduced by 1968 to a superintendent and a ranger. Also employed by the Park Service were a receptionist and a maintenance man, but their services were shared with the Forest Service, as was the obligation for their salaries.

Bidding for the first contracts to develop the joint administrative site were closed in June 1964. The visitor center was completed in 1966, but remained closed to the public until 1968, when a bridge across the Middle Fork was completed.

Transition And Development

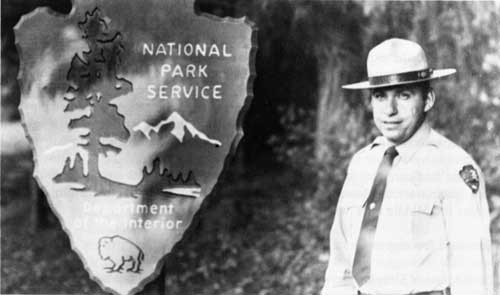

In April 1963, James Sleznick arrived at Gila Cliff Dwelling National Monument as its first full-time employee. [56] Previously a ranger at Lake Mead National Recreation Area, he came to the cliff dwellings as supervisory park ranger, a unique classification within the Park Service. [57] "Doc" Campbell continued as nominal custodian until the following January, when he retired.

For the first few months—until a bulldozer opened a track wide enough to haul an office trailer to the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon—Sleznick operated out of the Gila Hot Springs Ranch, where parking space had also been rented for two other trailers, one of which served as his residence. Typically, the accommodations were spartan, but in this case there were idiosyncracies, as well. After Campbell's generator broke in the summer of 1964, for example, there was no electricity in the government housing for 18 months. Years later, Sleznick recalled that he and his wife used candles at night, preferring dim light to the hissing of a Coleman lantern. [58] Refrigeration was provided by a Servel unit that was powered by propane; unfortunately, it had an electric thermostat. The only way to operate the refrigerator without freezing everything was to fire up the unit at dark and then shut it off at bedtime. Forgetfulness meant a hard breakfast. To the surprise of visitors, the toilet was plumbed to distinctly hot water from the ranch's namesake springs, and in the winter cold water had to flow all the time to keep pipes from freezing. When "Doc" finally installed another generator, a light also had to be left on to provide the "load" required for efficient operation.

|

| In 1963, James Sleznick arrived a Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument as the first full-time staff. Initially designated a supervisory ranger because the monument was too small to merit a superintendent, Sleznick was promoted to superintendent in 1966 as visitation to the remote monument increased. One of Sleznick's early capital improvements was a more substantial contact station, which he heated with a Coleman lantern during the winter and shaded in the summer with juniper boughs spread over a ramada. |

After the office trailer was moved, Sleznick forded the river four times every day to get there and home again. In the winter, he had to spray his frozen wheels each morning with hot water from the garden hose, and before he could drive home he had to crawl under the pickup and heat the wheels again with a propane torch. The first winter, he also kept a lighted Coleman lantern under his desk for warmth.

By late April 1963, the approach road had nearly been completed as far as the confluence of the East and Middle forks. The imminence of that event, in fact, coupled with anticipations of a huge turn out for the annual jeep caravan, had dictated the timing of Sleznick's transfer to the monument. [59] When he arrived, however, the first bridge had not yet been built, and Sleznick had been forced to park his car at the confluence and accept a ride for the last five miles, crossing the river 14 times. Still, 433 other people also reached the cliff dwellings within the month. [60] Beyond the rough passage, these visitors had to contend with two closed gates through the Heart Bar Ranch and only a hand-lettered sign to confirm their route. [61] Some people wandered a long time along the dirt road that was State Highway 527 looking for the monument.

In August, after the bridge at the confluence had been opened, the approach road completed as far as Little Creek, and the easement through the Heart Bar more clearly signed, 2165 people toured the prehistoric site. [62] As the road continued to improve, more and more visitors arrived. In 1966, the target year for the MISSION 66 program, 24,000 people toured the cliff dwellings, nearly twice the number the Park Service had forecast six years earlier.

In addition to monitoring the ruins and interpreting them to a rapidly growing number of visitors, Sleznick participated in drafting the master plan and later troubleshooting on the construction grounds. Each summer, a seasonal employee was hired to help with interpretation, and in late 1965, after the annual number of visitors had approached 15,000, William Gibson was transferred from Morristown National Historical Park to provide additional interpretive support. [63] Shortly afterwards, Sleznick was promoted to superintendent. [64]

Naturally, there were plenty of problems for Sleznick to troubleshoot in developing an area that was for all practical purposes entering the twentieth century nearly 60 years later than the rest of the country. When construction began on the visitor center in 1964, for example, contractors had to haul their materials 40 miles through the mountains, and road improvements did not extend beyond Little Creek—four miles and one river crossing short of the administrative site. In fact, this last stretch of road was not completed until early 1967 so even the installation of utilities and the construction of employee housing, as well as the barn, were also difficult. Occasionally, floods required work to stop altogether. And there were the usual kinds of construction problems: poor concrete required foundations to be removed and redone by a different contractor, blasting to enlarge the parking lot at Cliff Dweller Canyon threw boulders through the outhouses, gas lines were broken by a bulldozer.

Compounding the physical isolation of geography was an unreliable telephone system that made the coordination of development projects particularly difficult. For any important calls, Sleznick had to drive 50 miles. Other calls were made on a no. 9 magneto-wire that stretched from the Heart Bar headquarters through "Doc" Campbell's ranch to the Mimbres Valley, where it tied into a commercial system. Shortly after Sleznick arrived at the monument, however, the local telephone company upgraded its equipment and the new system would no longer accept the magneto-wire transmissions. "So we needed 40 miles of new telephone wire," Sleznick recalled years later.

Since members of the Upper Gila-Sapillo Telephone Company, which included the Park Service and the Forest Service, did not have enough money to buy the wire, Sleznick found some free surplus wire at Fort Bliss. With local help, he began unrolling the wire between the Mimbres District Ranger Station and the monument.

[W]e would take a reel of wire and put it in a jeep and drive off to a point where we had ended with the last roll. Then we would tie the cable to a horse with a rider, and the horseback rider would pull the cable until the quarter-mile was used up. When we saw the cable had come to the end of the reel we had a pistol—we didn't have radios—and we fired a shot. The cowboy would hear the pistol report and stop the horse, drop the cable, and we would find him with the next roll....

[The cable] was laying on the ground. We never did get it in the trees. What happened was we laid it all out, got it all soldered, hooked up—and it didn't work. [65]

When the Forest Service required him to remove the useless wire, Sleznick ran an advertisement in the Silver City Daily Press that 40 miles of wire was lying on the ground between the Mimbres and Gila Cliff Dwellings and that the wire would be free to anyone who went out and got it. Slowly, the wire disappeared. Another line was run, but the phones still did not work reliably when Sleznick transferred in 1967 to the Virgin Islands. Although the telephone system resisted his resourcefulness and resolve, those traits did contribute directly to the successful development of the monument under very difficult circumstances. By the time Sleznick left, construction had essentially been completed, the trailers moved from Campbell's ranch, and the residences opened to the superintendent, his ranger, and their families.

Replacing Sleznick was William Lukens, who arrived at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument in September 1967. [66] Although he had to contend with some additional problems of construction—underground electric cables were shorting out, for example—Lukens spent most of his time improving the interpretive program at the monument. He coordinated the ongoing development of exhibits for permanent display in the visitor center, supervised their installation in 1968, and organized the ceremonial dedication of the building a year later. Lukens also participated in planning a major stabilization of the cliff ruins, which occurred in 1968 and included the construction of the current one-way loop trail from the contact station through the ruins and back.

A new factor in managing the monument was the occupation by staff from the Gila National Forest of their assigned offices in the visitor center. They had arrived shortly after commercial power and telephone systems did, in early 1968. [67] Although the Park Service and the Forest Service had previously cooperated amiably and very effectively during the earlier planning and construction phase of the monument improvements, Sleznick and his staff had nevertheless enjoyed a relative independence, which their physical isolation had entailed. Lukens, in addition to his professional responsibilities, now had to meet the daily challenge stemming from the occupation of one small site by staff of two large and historically rivalrous agencies.

Despite close quarters, overlapping duties, and the novelty of interdependence, cooperation between the two agencies was exemplary. Visitors to the monument, which was managed by the Park Service, often stayed overnight at the Scorpion Corral Campground, which was managed by the Forest Service, and both agencies alternated in hosting campfire presentations. When Don Morris, an archeologist with the Park Service, came to survey prehistoric sites around the visitor center, he was helped by Joe Janes, the naturalist for the Gila National Forest. At the request of the Forest Service, Morris also made recommendations regarding the preservation of Grudgings Cabin, a historic site near the monument. Not long afterwards an exhibit specialist from the Park Service's Harpers Ferry Center wrote a thoughtful assessment of a nature trail that the Forest Service had developed between the pictographs at Scorpion Corral and a two-room ruin farther up a side canyon. In 1968, Joe Janes interpreted the cliff ruins while Lukens and his ranger were called to fight a wildfire. In short, interagency cooperation at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument ranged from implementing coordinated strategies for more effective resource management to coping with unplanned contingencies.

Once a year, the regional directors of the Park Service and the Forest Service met to coordinate their budgets for operating and cyclic maintenance expenses. Lukens made his budget and management recommendations to his superiors in Santa Fe, but he commonly sought advice and the resolution of quotidian problems from the forest supervisor in Silver City. "Dick Johnson was almost the same as my supervisor," recalled Lukens in 1991. "If I had a problem, it was easier to work with Dick than the region because of "Doc" [Campbell's] radio-phone." [68] The radio-phone made calls to Silver City easier than calls to the regional office in Santa Fe, which entailed a long drive to a phone with an adequate long-distance connection.

There were, of course, a few cracks in this solidarity. A 1972 inspection report prepared by the forest supervisor acknowledged some frustrations in the "growing up stages" of the joint occupation. [69] The report noted that the cramped living conditions were conducive to a kind of edginess commonly associated with cabin fever. It also included a laconic observation about the complicating effect of the Park Service possessing a superior position in an office building that was on Forest Service land. Earlier, a management appraisal by the Park Service had noted that the 1964 Memorandum of Agreement did not clearly define jurisdiction and lines of authority. [70] Although both agencies recognized the potential for greater conflict, frictions were minimal.

In 1971, when his children were ready for school, Lukens transferred to the less remote Chiricahua National Monument in southern Arizona. Replacing him on the upper Gila was Elroy Bohlins, who continued the cooperative nature of the monument's management program. [71]

Transfer To The Forest Service

Meanwhile, far from the headwaters of the Gila River, an important controversy was unfolding around the acquisition by the Park Service of two large tracts of land—the Gateway National Recreation Area outside of New York and the Golden Gate National Recreation Area near San Francisco. Critics were concerned that the expensive operation of these urban recreational facilities had essentially been allotted to the Park Service by default, that these "gateways" benefited only the local population, and that they should consequently be managed by other agencies, preferably state or regional ones. Although the "Gateways" remained in the national park system, the director formally responded to the concerns by revising in 1975 the criteria for future parks. In short, the Park Service no longer—or at least not ordinarily—proposed to acquire areas that another agency could adequately protect without severe limitations to public access.

Even before the criteria were revised, George B. Hartzog, Jr., who had presided over the Park Service during the "Gateway" expansions, suggested to his regional directors that they watch for opportunities to reduce their administrative burdens by identifying assets that might logically be operated by other agencies. [72] Joseph Rumburg, the Southwestern Regional Director, recognized in Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument just the kind of place Hartzog seemed to have in mind. [73] Already, the monument's headquarter facilities were shared with the Forest Service. The daily cooperation of staff was well-known, and the two agencies had demonstrated the compatibility of their management policies during the coordinated development of the monument, the Scorpion campgrounds, and the joint administrative site.

In August 1974, the retirement of Elroy Bohlins, who had a few years earlier replaced Lukens as superintendent, presented an opportunity to experiment with Hartzog's suggestion. Within a month, Rumburg wrote to the regional forester, proposing that the Forest Service assume primary responsibility for operations at the monument. He cited as justification the elimination of needlessly duplicated efforts, financial economy, and the proportionally deeper commitment to the area that managing the Southwest's largest wilderness required of the Forest Service. [74] A joint feasibility study in October revealed that $35,000 in annual operating costs could be saved were the monument to be managed by a single agency. [75]

In January 1975, Robert Williamson, supervisor of the Gila National Forest, endorsed the study. [76] Concurring with Rumberg's justifications, he also noted that the assumption of administrative responsibility at the monument was an opportunity to increase much needed district staffing, an increase that would "benefit the complete rangerment of the Wilderness District, especially as it relates to Wilderness recreation and range resources." [77]

Ultimately, a new cooperative agreement was drawn up between the Forest Service and the Park Service, and Rumberg's signature on April 14, 1975, consummated the transfer of administrative responsibility for Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. [78] The new agreement terminated the 1964 document, although it called for the Forest Service to operate the monument according to Park Service standards, a responsibility that entailed providing all staff, enforcing appropriate laws and regulations, and preparing regular reports. In turn, the Park Service agreed to make available all property that it carried on the monument's books, to provide technical assistance for interpretive displays and archeological stabilizations, to train personnel, and to reimburse the Forest Service for all costs that it incurred under the cooperative agreement. Furthermore, the Park Service was to perform all archeological salvage and to maintain a schedule for development projects, as well, which would be funded through its own normal budgeting processes. In other words, the Forest Service was to be responsible for the daily operation of the monument, and the Park Service would provide money, expertise, and strategic planning services.

Forest Service Management Of The Monument

To date, the 1975 Cooperative Agreement has functioned well. As they have done since 1964, representatives of the Forest Service and the Park Service meet once a year to review issues of management, maintenance, and preservation; to resolve any problems; and to settle on an appropriate budget. In 1987, the associate regional director of park operations noted that "the working relationship has seemed to improve with each year." [79]

As agreed, forest staff manage the day-to-day administration of the monument, and these positions are funded by the Park Service. In addition to interpreting the monument, keeping it physically up to standard and implementing recommendations made by the Park Service, the Forest Service has contributed significantly towards planning for the future by producing two well-received plans for resources management, the 1976 Statement for Management, and the 1986 Statement for Management. For its part, the Park Service has since 1975 sponsored three stabilization studies and performed two stabilizations, one of which was a site in the Gila National Forest. It contracted the development of an interpretive prospectus as a guide for improving the interpretive program, the visitor center, and the contact station. It contracted the research necessary to document the monument for the National Register of Historic Places. And it has also programmed funds and time for its own staff to research and publish a detailed analysis of artifacts recovered earlier at the cliff dwellings; to map and sample the surface of TJ site and to publish the attendant facts; and to resurvey all archeological sites on the monument.

In short, the transfer of daily administrative responsibility has not at all diminished the professional stewardship of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. The ruins continue to receive appropriate and timely measures of protection, the physical plant is maintained regularly, and interpretation has been substantially enhanced by the increasing amount of research. At the same time the Park Service has again saved money. The number of people permanently and exclusively employed—and therefore paid—for the benefit of the monument has declined from four in 1974 to a park ranger and a lead guide in 1990, who spend most of their time on interpretation. [80] To administer resource management and maintenance programs, the Wilderness District ranger, who doubles as the superintendent of the monument, and the district resource assistant now divide their time between the monument and more typical duties. [81] In turn, the Forest Service has been able to expand its staffing on the short-handed Wilderness District—just as Supervisor Robert Williamson had hoped. With new funds and an additional mandate, the district staffing increased from four permanent positions in 1974 to 11 within three years. [82]

The only real problem stemming from the transfer of administrative responsibility was the novelty of archeological interpretation in the Forest Service. Since there was no clearly defined career track for that role within the bureaucracy, one interpreter—an ambitious and conscientious employee—labored under the ill-fitting title of park historian for nearly 10 years and under three different district rangers before another suitable position opened elsewhere.

This problem was finally resolved in 1986 with yet another interagency agreement. [83] The Park Service agreed to canvas its own employees for assignment as park ranger at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, and the Forest Service agreed to hire one of those applicants. In addition, it was understood between the two agencies that this ranger would be re-employed by the Park Service after a tour of duty at the monument lasting not less than two years and not more than three. Since 1986, two permanent employees of the Park Service have accepted the limited transfer to the Forest Service.

Undoubtedly, the transferal of administrative responsibility in 1975 was facilitated by a history of interagency cooperation that had increased gradually and in clear increments. Rumburg's signature was just another step down a trail first blazed when Frank Pooler directed the supervisor of the Gila National Forest to build a fence to protect a rival agency's monument. Inevitably, the narrow constraints of canyons and flood plain pushed the agencies closer together as each contemplated developing cultural and recreational resources on the forks of the Gila River. After years of accommodation in a small place, the applied mandates of the Forest Service and the Park Service now fit comfortably together.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

gicl/adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 23-Apr-2001