|

Gila Cliff Dwellings

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter II:

HISTORY OF TENURE AND DEVELOPMENT 1933-1955

EXECUTIVE ORDER 6166

On June 10, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6166, an act that transferred to the Park Service control of "public buildings, national monuments, and national cemeteries." [1] The act was the culmination of many years of lobbying by Stephen Mather, the first director of the Park Service, and of his successor Horace Albright. This administrative reorganization effectively doubled the number of units managed by the agency. Included in the transfer was Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, as well as all the other national monuments administered by the Department of Agriculture and the Department of War.

Beyond the new prominence that is commonly proportional to size, the reorganization also gave the Park Service a substantial presence east of the Mississippi River, where most of the American people lived. At stake, Albright confessed years later, was the survival of the agency's political independence. Before 1933, the influence of the Park Service had been limited almost exclusively to remote areas in the largely unpopulated lands of the American West. Executive Order 6166 gave the agency a genuinely national scope and constituency as well as a new mandate, making "the Park Service a very strong agency with such a distinctive and independent field of service as to end its possible eligibility for merger or consolidation with another bureau." [2] Specifically, that "bureau" was the Forest Service, which since Gifford Pinchot's administration had challenged the necessity of its rival.

In addition to giving the Park Service jurisdiction over further natural and scenic resources, the reorganization and the Historic Sites Act that was passed soon afterwards gave the agency sole responsibility for preserving the nation's archeological and historical heritage, a field in which the Forest Service had no standing.

During the bureaucratic tug of war that had accompanied the establishment in 1916 of the Park Service, legislation to consolidate the administration of all the national monuments in the new agency had been challenged vigorously by the Forest Service. Later, the proposal had been dropped. In 1933, however, the Forest Service was slow in responding to Executive Order 6166, which again proposed consolidation. For largely unknown reasons, opposition was not formally expressed until late September, more than six weeks after Executive Order 6166 had become effective. Based on a loophole in the legislation, the secretary of agriculture appealed the transfer belatedly, observing that the monuments "were essential to the work of this department and should not therefore be transferred." [3]

Complicating the orchestration of clear and forceful opposition on the part of the Forest Service was a confusing dialogue that its staff was having with representatives of the Park Service. Initially, it seems, the Park Service did not propose to acquire all 16 of the monuments that lay within boundaries of the national forests. Precisely which monuments were wanted, however, is not clear from the historical record. By different authorities, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument is cited as one the Park Service did want and one that it didn't want. [4] The administrative fates of Sunset Crater, Tonto, Walnut Canyon, and Chiricahua national monuments were clouded by the same ambiguity.

This confusion may also have stemmed from conflict within the ranks of the two agencies as well as between them. In the Park Service, for example, Frank "Boss" Pinkley, the notoriously independent superintendent of Southwest Monuments, certainly opposed the establishment of Saguaro National Monument, an acquisition the Washington office was actively promoting. [5] In this way, dialogue between agency officials at the local Southwestern level and their ensuing recommendations may have conflicted with the larger and political interests of the central bureaucracies. This conflict may have generated the kind of contradictory correspondence that has been preserved.

Whatever the complexities and perceptions may have been, the appeal was rejected and a negotiated division of jurisdiction over the monuments also failed. On January 28, 1934, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes reported that the administration of all the Forest Service monuments had indeed been transferred. [6]

An unfortunate legacy of the inconclusive dialogue between the two agencies was an embittered perception that the Park Service had reneged on a verbal agreement to take only some of those monuments. For years this sense of betrayal additionally strained an already contentious rivalry. [7]

Pinkley And The Southwestern National Monuments

Less than a week after the September appeal had been formally denied, Pinkley was notified by his superiors in Washington that Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument had been transferred to his jurisdiction. He was directed to inquire whether Forest Service funds or personnel should be transferred along with the monument. [8] As it turned out, neither men nor money was to supplement Pinkley's new responsibilities.

The superintendent of the Southwestern National Monuments, however, was a man long accustomed to limited budgets. [9] With few assets beyond his own rough charisma, "Boss" Pinkley had in the preceding 10 years organized the widely scattered and largely volunteer custodians of those Department of the Interior monuments that were in the Southwest into a professional staff that accommodated a large number of visitors on a near pittance. In 1927, for example, 270,000 people visited the Southwestern Monuments for which the Park Service had allocated only $15,000; in the same year, Grand Canyon National Park, which drew only 162,356 visitors, received more than $132,000. [10] Obviously, Pinkley had to be tight with his money. Equally apparent, to Pinkley and to contemporary historians as well, was a disproportion in funding that signaled a hierarchical distinction at the time between national parks and mere national monuments.

Meager funding was not Pinkley's only administrative problem. Before and after his appointment as superintendent of Southwestern Monuments, the more scenic monuments were gradually being elevated to the superior status of parks. Eventually, it seemed, the monuments might only represent the culls of the Park Service properties. Certainly, Pinkley's concern had substantial justification: eight of the 12 national parks currently designated for the American Southwest began as national monuments, including Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon, Zion, and Carlsbad Caverns national parks, which were all redesignated during Pinkley's tenure with the Park Service.

This evolution of status had its root in a very utilitarian feature of the Antiquities Act of 1906, the original enabling legislation for designating national monuments. These monuments were decreed by executive order of the president of the United States—independently of congressional authorization. National parks, on the other hand, were the legal products of substantial and often lengthy wrangling in Congress, where the interests of potential resource developers and the foibles of several hundred individual congressmen complicated the legislative mechanics of preservation.

The facility of an executive order had quickly attracted the attention of those interested in preserving American landscapes. In 1908, for example, President Theodore Roosevelt used his authority under the Antiquities Act to set aside a little more than 800,000 acres as Grand Canyon National Monument and a year later 600,000 acres as the Mount Olympus National Monument. [11] In these cases, Roosevelt possibly exceeded the originally envisioned scope of the Antiquities Act. But the creative application of this legal instrument did protect threatened land quickly and for a long time without effective challenge. Later, in a more leisurely way, many of the properties were negotiated up to the status of national park through the uncertainties of partisan agencies, congressional loyalties, and other political hurdles.

In short, during the formative years of the Park Service, the directors of that agency favored large scenic parks over monuments and allocated far more money and attention towards developing the former category. Meanwhile, monuments commonly languished unless there were plans for eventually transforming the property into a park.

Unfortunately, by the time Executive Order 6166, the Historic Sites Act, and other New Deal measures provided the Park Service with increased funds and a dominant role in the preservation of the nation's historic and prehistoric heritage, Pinkley's embittered frustration over years of meager budgets and the erosion of his administrative demesne had isolated the "Boss" from the Washington office, where he had come to be viewed as a "cantankerous, aging iconoclast." [12] By 1933, Pinkley no longer had sufficient weight and influence to successfully balance his own agenda against the agency's new tilt towards the more populous East. There, the inspiring legacies of the American Revolution and Civil War simply drew more interest and dollars than remote Indian sites.

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument

In 1934, isolated in the heart of the largest legislated wilderness in the Southwest, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument was the most remote of the monuments under Pinkley's jurisdiction. Although in earlier years he had argued the merits of transferring control of all prehistoric sites to the Southwestern Monuments group, Pinkley's ambition was constrained by the site's inaccessibility, low budgets, a small staff, and possibly the initial confusion over the monument's status.

Not until the following year did Pinkley even send an agent to assess the monument he had inherited from the Forest Service. In March 1935, G. H. Gordon, an assistant engineer for Southwestern National Monuments, became the first employee of the Park Service to see Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Gordon arrived on horseback after riding 20 miles through the wilderness. Subsequently, he said in his report that the ruins were indeed worthy of recognition, [13] a comment suggesting a debate that has largely faded from the record. [14]

Included in Gordon's report were a ground plan of the ruins and five recommendations for the development of the monument: (1) constructing an approach trail; (2) formally mapping the ruins and including them on the stabilization program; (3) building a fence across the canyon, above and below the ruins; (4) surveying the area of the monument; and (5) appointing a local "dollar-a-month" custodian.

No immediate administrative action sprang from these recommendations.

National Park

The next official visit to Gila Cliff Dwellings did not occur until the autumn of 1937, when a team of Park Service staff came down from the new regional office in Santa Fe [15] to assess the merits of creating a national park on the headwaters of the Gila River. In their report, the team recommended establishing a park and suggested that it take in 563,000 acres of the Gila Wilderness—essentially all of the wilderness west of the East Fork. [16] Subsumed in the proposal was Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, the ruins of which were judged by Erik Reed, the regional archeologist and a member of the team, to not merit national park status. They would, in his opinion, make interesting supplements to a park that preserved a dramatic natural area of canyons and pristine forests, however.

The preserved record of this proposal is sparse, and the proximate causes of its failure must be deduced from a larger context and a little close reading. Undoubtedly, the greatest obstacle to the creation of the national park was the fact that the very large tract of land being considered was administered by the Forest Service. In the Southwest, the Forest Service had already seen more than a million acres transferred from its jurisdiction through the establishment of national parks. [17] Recently it had vigorously and successfully resisted the creation of Cliff Cities National Park at what is now Bandelier National Monument, a proposal that would have entailed yet another large withdrawal. [18] Given the perceptions of betrayal that had accompanied the absorption of all national monuments previously administered by the Forest Service and the contemporaneous inter-agency struggles over Olympic National Park and King's Canyon National Park, it was inevitable that any proposal entailing a national monument, large tracts of land, and the creation of a new national park would be viewed through extremely narrowed and wary eyes.

Furthermore, the land proposed for Gila National Park already had unique status as the nation's first wilderness area and as the largest in the Southwest. The Gila Wilderness was a showpiece of Forest Service restraint, demonstrating a commitment to recreation and to the preservation of natural values that matched the efforts of its rival agency. [19] Transferring this wilderness would not only reduce the Gila National Forest by 25%, it would also usurp the efforts of the Forest Service to display clearly and imaginatively its mandate beyond watershed protection and the mere economy of resource development.

Finally, an image of independent responsibility and consequence was especially important during the late 1930s, when Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes was lobbying actively and with substantial—even presidential—support to transfer the Forest Service from the Department of Agriculture to his own agency. [20] Even a tacit acknowledgement that the Department of the Interior could do a better job managing the natural values of the Gila headwaters or of any other reach of national forest might be seen as damaging.

In 1938, the proposal for establishing Gila National Park was made. A year later, this proposal had been modified. Instead of a new large national park, an even larger national monument—650,000—was proposed that would again include the current Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. [21] Unclear is whether this modification was an accommodation to the 1,500 acres of patented mining claims, which could then still be legally developed, [22] or was instead the well-known legislative back door that would transfer most of the wilderness by executive order, avoiding in this way opposition that the Forest Service might already have mustered in Congress. Designation as a national park could always come later.

In January 1940, the acting director of the National Park Service circulated drafts of a letter of transmittal to be signed by the Secretary of the Interior [23] and of a presidential proclamation that excluded approximately 654,400 acres from the Gila National Forest. It was, the proclamation stated, "in the public interest to reserve such lands, together with the lands now comprising the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument as a National Monument, to be known as the Gila National Monument." [24] Neither document was ever signed.

A little more than a year later, Minor Tillotson, the new director of Region III of the Park Service, recommended that Gila Cliff Dwelling National Monument "be left as a reserve area with no attempt to popularize it and promote visitation." [25] The gap between this recommendation and the presidential proclamation that had circulated not much earlier is profound; unfortunately, it can only be spanned with inferences based on the broader territorial struggles between the Forest Service and the Park Service, on the specific logic of conflict over the Gila Wilderness, and possibly on the appointment during the hiatus of Newton B. Drury as director of the National Park Service. Drury was a man who quickly proved to be considerably less expansionist than his predecessors. [26]

The idea of Gila National Park failed, and its only documented consequence was the construction in 1938 of a fence to bar cattle from the ruins in Cliff Dweller Canyon. This project stemmed from a complaint made by a member of the park assessment team about livestock trampling the site. [27] Following an exchange of letters, Frank Pooler, the regional forester directed an initially recalcitrant Gila National Forest supervisor to comply with the request for a fence. [28]

Pinkley never saw Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. [29] Given his well-known disinclination to see archeological sites become parks instead of monuments, however—an attitude that he demonstrated over the issue of Cliff Cities National Park—and given his expressed frustration over the elevation of Carlsbad Caverns from national monument to national park, Pinkley's feelings about the proposed Gila National Park can probably be intuited. Perhaps his likely intransigence contributed to the fact that no member of his Southwestern National Monuments staff was included on the 1937 park team to assess the Gila proposal, a curious and provocative omission. At any rate, after 1935 no funding and no staff were allocated to this monument for the rest of Pinkley's life. Pinkley died before the issue of the larger Gila National Monument was shelved.

Reserve Monument

After his visit to Gila Cliff Dwellings, Regional Director Tillotson alluded to the 1937 report by the park assessment team, but he did not mention their recommendations for a national park on the headwaters of the Gila River. Obviously, by August 1941, that book was closed. About the ruins themselves, he made his own assessment, noting that "from the standpoint of an ordinary tourist, I would not consider it worthwhile to visit them in view of their inaccessibility and the cost and time involved." [30]

Undeniably, Gila Cliff Dwellings was not an easy place to reach, and the rigors of Tillotson's visit are instructive. After driving 27 miles of dirt road from Pinos Altos, he arrived at the locked gate on Copperas Flat, which barred all motorists from descending to the Gila River without a key and the consent of those who lived on the few sections of private land along the water. For convenience, however, there was a telephone booth near the gate. Using this Forest Service magneto-line, which connected to the river ranches as well as the fire lookouts, visitors could announce their presence at the Copperas gate. Tillotson called Dawson "Doc" Campbell, who had recently bought the historic ranch where members of the park assessment team had stayed four years earlier. Years later, Campbell recalled the regional director's arrival:

Tillotson had trouble finding [the cliff dwellings]. They gave him a wrong steer, and he went to [?]. Then he came back and got on the right road. There was a road of sorts at the head of Copperas up here...He got to the telephone, and he called. I was out with a party, packing in and gone all day. Well, Mrs. Campbell took the message and sent a boy that was staying with us with a horse up there to pick him up.

There came a gosh-awful storm. I mean it was a real gully washer. And the boy got there, and it was dark and raining, and he couldn't find him. [The boy] called from up there [...then] he started back...As soon as daylight, I went to look for [the boy]. He hadn't come in. Then I found him. His horse had taken him off the trail, and he had slept under a tree that night.

Well, when I got on back, Mrs. Campbell said [Tillotson] had called again and wondered where that boy was. He had slept in the car all night. So, anyhow, I grabbed the makings of coffee and some sandwiches, and I went there and picked him up.

[The trip from Copperas to the Campbell ranch] took two hours if you were riding briskly...For a long time, we had 19 river crossings to get here. [31]

In his report, Tillotson did not mention wrong directions, hard rain, a long hungry night in his car, and 19 river crossings. But these factors may well have been included with the 27 miles of dirt road and 14 miles on horseback when he weighed the merits of the cliff dwellings against the time and cost of just getting to them. Noting that inaccessibility rather than government action had been the primary source of protection, Tillotson recommended that Gila Cliff Dwellings be managed as a reserve area and that visits be discouraged in part by deleting allusions to the site from the promotional literature for the Southwestern National Monuments.

For the next 14 years—as long, it so happens, as Tillotson was regional director—this recommendation was the applied philosophy of management for Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Tillotson also recommended the stabilization of existing walls, which—in his words—displayed the usual evidence of vandalism; the provision of a binder for standard registration sheets and a water proof container; and the construction of a foot-trail from the bottom of Cliff Dweller Canyon to the ruins, as well as "sufficient fencing" to exclude cattle. He concluded with a suggestion that the monument be visited at the first opportunity by Hugh Miller, the new superintendent of Southwestern Monuments.

|

| The only link from the remote monument to the twentieth century was a steep track through the Gila Wilderness, over very difficult ground. This old wagon road could only be negotiated by horses and trucks with special gearing. |

Three weeks later, Miller arrived at Gila Cliff Dwellings, accompanied by Dale King, a staff naturalist, whose venture to the remote site included a fall from his bucking horse into barbed wire—another demonstration that distance was not the only factor when calculating the prehistoric architecture's accessibility. Although the superintendent found the monument to be "an interesting unit in delightful country," he concurred with his superior's suggestion about managing it as an undeveloped archeological reserve. [32] Still, noting with some surprise that three or four hundred people visited the site each year, Miller did additionally suggest that "Doc" Campbell, who lived only seven miles from the monument and who was already a deputy sheriff, be hired as nominal custodian.

Campbell And The Reserve Monument: 1942-1955

Originally from Pennsylvania, Campbell had come to the Southwest in 1930—when he was 17—for adventure and relief from hay fever. Drawn by New Mexico's largest wilderness, he had ridden a burro the same year to the forks of the Gila River and trapped fur all winter—without much success. In the spring, he found more reliable employment wrangling a pack string on the Gila Hot Springs Ranch, the small resort that had been developed by the Hill brothers in the 1890s and the same place at which Bandelier had stayed during his visit to Gila Cliff Dwellings in 1884. Later, Campbell worked eight years on the XSX Ranch on the East Fork before purchasing in 1940 the 320-acre Gila Hot Springs Ranch, which he continued to operate as a guest ranch and base for his guide service into the wilderness. [33]

On April 1, 1942, based on Miller's recommendation, Campbell was appointed nominal custodian of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, a responsibility that entailed inspecting the ruins once a month for structural damage and advising ranchers and other local guides about rules that prohibited digging for artifacts, knocking down walls, writing graffiti, "and other vandalisms or thoughtless practices which might be destructive to the ruins." Damage was to be reported immediately to the Southwestern National Monuments office in Casa Grande, Arizona; otherwise, a monthly report sent on a regular date would be sufficient. All in all, he was advised:

We want you to be our local representative to keep us constantly in touch with the situation at the Gila Cliff Dwellings by acting as a combination godfather and wet nurse to those somewhat neglected but very valuable and interesting dwellings. [35]

In return for these services, Campbell received a check twice a month for 46 cents—that is, a dollar a month, less an eight-percent deduction for his retirement fund. [36]

In 1990, Campbell recalled the early years of his nominal employment at Gila Cliff Dwellings with the following observations:

[W]e made several trips up there. Sometimes once a month, sometimes much oftener. We filed a monthly report. We answered the mail. Now they did furnish stationary and envelopes—stamped envelopes—and they did have...an information sheet that we could enclose. Mrs. Campbell had been a secretary in the civil service, and so she did the typing. We had a portable typewriter, and she did the typing to respond to [inquiries...]

Now, in those days—particularly in wintertime—you didn't get mail very often. We might get a letter once in a while...I wrote [the Washington office of the Park Service] a letter and told them how things were out here, and I mentioned the fact that we sent mail in sometimes when anyone was going in the general direction of the post office [in Silver City]. I got wires out of Washington relayed by telephone: "Where's that report?" That stopped that. But anyhow, we did make the reports—how many visitors and what had happened....

And we maintained that trail. And the trail was maintained as a family. We'd usually go have a picnic, and go up there and rake the trail and fix it up—put in water bars, build some steps...It just went up the canyon, and it was a beautiful trail. People enjoyed it....

And then remember, we had no appropriation so any tools we used on the trail was our tools. We had no typewriter except our own. In other words, this was the way it was, and that was the way it had been by other rural areas. This was just kind of customary, I guess .... [37]

In his role as a wilderness guide, Campbell also provided tours of the ruins for the paying guests who stayed at his ranch. In 1942, for example, the same year he was appointed custodian, all but six of the 196 visitors who signed the register had either been guests at his own Gila Hot Springs Ranch or at the nearby Lyons Lodge. [38] Ultimately, the coincidence of Campbell's custodial and hospitable responsibilities as well as his own curiosity elicited the first archeological overviews of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, one from Charlie Steen [39] and one from Erik Reed, [40] who were staff archeologists with the Park Service. Both overviews had been researched and written at Campbell's specific request.

Beyond the fortuitous hiring of Campbell, who had a personal interest in the ruins, the Southwestern National Monuments office limited its investment in the isolated monument to the minimal recommendations of Tillotson. No visitor facilities were constructed, but the ruins were stabilized, using $390 that had been allotted to that end. Although modest, this figure compares favorably with the $240 spent in the same year at Chaco Canyon.

In July 1942, an archeologist—Charlie Steen, in fact—was dispatched from Casa Grande to Gila Cliff Dwellings, where he spent five days with a hired man, shoring up walls with dry masonry, measuring for a ground plan, taking core samples of the beams, cleaning the site, and building a trail from the small stream in the canyon to the ruins. Also, he dug two exploratory trenches for sherds that could be used to infer cultural affiliations of the prehistoric site.

Decline

After 1942, the limitations of small, wartime budgets and a staff depleted by military enlistments [41] as well as the termination of the Civilian Conservation Corps program forced the Southwestern National Monuments office to scale back its management activities throughout the region to mere protection and maintenance. After the Second World War, the backlog of work at the larger, more visited national monuments further delayed the next official visit to Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Finally, in 1948, Steen was again dispatched to assess the condition of those ruins. Unfortunately, he reported substantial deterioration of the prehistoric architecture, noting that most of the damage had been caused by visitors. [42] Although he recommended excavation as well as another round of stabilization activities, no funds were allocated for this work.

As the most remote unit in the system of Southwestern National Monuments, with few visitors, no permanent staff, and only a reserve status, the prehistoric site in the Gila Wilderness suffered the kind of administrative desuetude that is occasionally the product of limited budgets, competing projects, and a long list of priorities. [43]

In June 1954, Marjorie Lambert, the curator of archaeology for the Museum of New Mexico, drew professional attention to the monument. Writing to Erik Reed, she complained about the condition of the ruins, which she had recently visited with members of the Grant County Archaeological Society. [44] Specifically concerned about damage caused by visitors walking on the walls, an activity she had apparently witnessed, she also lamented the amount of graffiti inscribed on walls, beams and pictographs, noting that "[t]hese ruins are one of the saddest examples, in the Southwest, of this sort of vandalism."

Lambert's letter triggered an inquiry from Southwestern National Monuments that led, in the following year, to the hiring of "Doc" Campbell as the first seasonal ranger at the monument and shortly afterwards to a six-week visit by the Mobile Stabilization Unit to remediate damage inflicted on the prehistoric site. [45]

Gila Forks: Roads And The Primitive Area

Since 1941, based on Regional Director Tillotson's recommendations, Southwestern National Monuments had more or less officially relied on the cliff dwelling's isolation in the heart of the Gila Wilderness to protect it from vandalism. In the years between Tillotson's visit and Lambert's, however, the degree of isolation had begun to decline. In 1944, the lock was removed from the gate on Copperas Mountain, making the road accessible to anyone who had a sufficient vehicle, and during his visit in 1948, Steen observed that the wilderness fence itself had been moved by the Forest Service nearly to the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon. The following year, "Doc" Campbell subdivided his Gila Hot Springs Ranch, and property owners along the river petitioned the Forest Service for permission to bulldoze—at their own expense—an alternate route to their inholdings, citing their protected rights of ingress and egress. The improved route descended along the "old military road" to the confluence of the East and Middle forks of the Gila River, a shortcut that eliminated some of the steep grades of the road into Lyons Lodge, as well as several river crossings.

The consequences of the improved access were predictable: whereas only six of the 196 people who signed the monument register in 1942 had provided their own transportation. In 1950, 186 of the 291 signatories reached the prehistoric site on their own; and in 1951, the proportion was 236 of the 302 visitors. [46] Although the total number of visitors was still small, the proportion of visitors unaccompanied by guides from the nearby guest ranches like Campbell's was rising dramatically, a temptingly unmonitored situation that led to idle digging in the ruins by hunters, fishermen and others, as well as the kind of graffiti that commemorated their visits.

Meanwhile, the Forest Service had begun reassessing the boundaries of the Gila Wilderness as the agency prepared to reclassify the area's protective provisions from Regulation L-20 to the more restrictive Regulation U-1. [47] Regulation L-20 was vague about the construction of roads, and by a textual omission it permitted motor vehicles into the protected areas. Regulation U-1 did not. Approved in 1939, the application of this regulation had been delayed by World War II.

In 1945, the supervisor of the Gila National Forest had been petitioned—also by residents on the forks of the Gila—to delete from special status the east side of the Gila Primitive Area, which included the road leading to the cliff dwellings. [48] In 1952, the Forest Service presented a proposal for new wilderness boundaries, which reduced the 563,000-acre L-20 Primitive Area to 375,000 acres of U-1 Wilderness. Most of the deleted area was north and east of the Middle Fork, where a lot of roads had been unofficially rutted into the easy terrain. Again, the Copperas road was included in the proposed deletion. More provocative was the proposed elimination of the well-timbered Iron Creek Mesa from the northwest side of the wilderness. Inevitably, the proposed revisions drew the prompt attention of such national organizations as the Sierra Club, the Wilderness Society, and the National Park Association, all of which opposed modifications to the wilderness boundaries and especially challenged the Iron Creek withdrawal.

As nominal custodian, "Doc" Campbell kept Southwestern National Monuments informed about the debate regarding roads and the reclassification of the Gila Primitive Area—and a little more. In 1949, for example, after reporting the increased likelihood of visits to the monument as a result of his subdivision, the new road to it, and an airstrip he had constructed, Campbell also prodded for development of the reserve. Three years later, he asked for "a definite commitment from your office on the Wilderness Area revision...," noting that he was in favor of the proposed reductions. [49] John Davis, the general superintendent of Southwestern Monuments, acknowledged Campbell's personal stake in the wilderness debate but emphasized the agency's neutrality in the debate about boundaries—as long as the monument itself was retained within the wilderness, an indirect reiteration of Tillotson's policy of isolation.

Ultimately, the debate over the wilderness revision was resolved in a compromise mediated by Clinton Anderson, New Mexico's junior senator and by a local ad hoc group that the Gila forest supervisor had appointed—the James Committee. [50] In early 1953, the boundaries of the area protected by Regulation U-1 were announced by the Forest Service: Iron Creek Mesa was retained in wilderness and most of the area east of the Middle Fork was retained under Regulation L-20 as a primitive area until "such time as further study and discussion with local people could resolve the differences of opinion." [51]

As an immediate result, the monument was no longer in the heart of the wilderness; instead, it was now on the administrative edge, buffered on the south only by the ambiguities surrounding motor vehicles in a primitive area. There was also a newly bladed road that nearly reached the ruins. In addition, the James Committee had specifically recommended that the Copperas corridor be formally extended to Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Although the recommendation was not included in the wilderness plan, a conceptual linkage between the prehistoric site and the construction of a good road was established—one that would provide considerable leverage in the near future.

1955: Roads And MISSION 66

In February 1955, the New Mexico legislature unanimously approved a house memorial—a non-binding form of legislation—that asked the State Highway Commission to construct an all-weather road from the Sapillo crossing to Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. [52] The urgency of this project, according to a contemporary newspaper account, stemmed from a growing popular interest in the monument and the wilderness. [53] Unlike the rough, privately financed road that had been bulldozed to the Gila Hot Springs subdivision in 1949, the new proposal sought public allocations for the construction of a road that would attract more tourists to Grant County. [54] Enticed by the prospect of more tourism, the Silver City Chamber of Commerce was already actively boosting the road proposal, and the Grant County Commission was exploring the pertinent costs of its construction. [55]

Also in February 1955, as a matter of coincidence, the American Automobile Association hosted a dinner in Washington, D.C., to inaugurate MISSION 66, a new 10-year program of the Park Service that was geared toward the construction of enough roads, visitor centers, and other facilities to accommodate the number of tourists projected to visit units in the park system in 1966—the 50th anniversary of the bureau. [56] The largest development program since the 1930s, MISSION 66 happened to require a prospectus for each of those areas, outlining its significance, its problems, and its potential.

For Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, Southwestern National Monuments developed a prospectus that echoed the earlier assessments of Tillotson and Miller, who was now director of the regional office:

The dwellings' well-preserved architecture and beautiful wilderness setting have combined to quiet any misgivings an analyst might develop concerning the adequacy of their national significance. [57]

Since the significance of these cliff dwellings was linked to their isolated setting, it followed then that the road memorialized by the New Mexico Legislature would diminish their status to "just another nice cliff dwelling." Therefore, the prospectus recommended that the Park Service consider transferring the archeological site to the New Mexico park system should the road ever be constructed and acquiring instead a large Mimbres pueblo site.

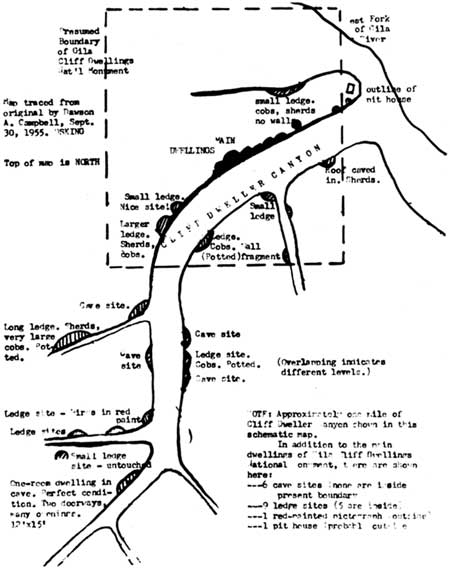

Campbell, who was working his first summer as a uniformed seasonal ranger, received the prospectus in early August. Recording his consternation in a memorandum and a more pointed letter sent on the same day to the general superintendent, he challenged the validity of the prospectus, noting among other things that the largely undocumented archeology of the area was far more extensive than commonly assumed and deserved a closer look. [58] With the help of Francis Parsons, president of the Grant County Archaeological Society, Campbell also identified near the monument just the kind of large Mimbres pueblo site in which the prospectus had expressed interest. In addition, he began drawing maps of all the other sites he could find. He also showed these sites to Roland Richert, a visiting archeologist from the Mobile Stabilization Unit who was supervising the stabilization work that Marjorie Lambert's 1954 lament had engendered.

With grab samples in hand, Richert enticed his immediate superior, Gordon Vivian, to spend some of his annual leave on the forks of the Gila River, beginning in this way a rapid sequence of letters and staff visits that led in November to a revised prospectus. [59] The revision was dramatic. The suggestion to transfer the monument was deleted. And the new prospectus recommended substantially expanding the unit to include new sites and especially the large and nearly pristine TJ Ruin at the confluence of the West and Middle forks. Earlier apprehensions about the national significance of the vandalized cliff dwellings yielded to a new recognition: on the upper Gila was a thickly clustered sequence of prehistoric sites, the rich legacy of a culture that was not represented elsewhere in the national park system. Not long afterwards, Conrad Wirth, the director of the Park Service, asked that the monument custodian be complimented for the vigilance that culminated in the revision of the prospectus. [60]

An interesting current also flowing through this administrative sea change was a discreet but repeated concern about the friends of local development, some of whom resided at Gila Hot Springs, and who—it was noted in the prospectus—"are exceedingly potent, who keep a close watch on National Park Service operations, and who will, whether the Service approves or not, see to it that Gila Cliff Dwellings is place prominently in the limelight, as needing preservation, interpretation, and development." [61]

Two of the well-connected friends of development were "Colonel" Clyde Ely, the editor and publisher of the Silver City Daily Press, and Chancie Snyder, who was president of the New Mexico Game Association and whose best friend and business partner was the campaign manager for Senator Clinton Anderson. Less wired politically but equally energetic was Francis Parsons, a retired architect from Massachusetts, who divided his time between the local archeological society, the city council, the chamber of commerce and boy scouts. [62] Both Ely and Snyder had summer houses at Gila Hot Springs, where other influential people lived as well. "At the time we sold this land," recalled Campbell more than 40 years later, "we had a president or active member—had past presidents—of every service organization [in Grant County]. [63]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

gicl/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 23-Apr-2001