|

Gila Cliff Dwellings

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter I:

HISTORY OF TENURE AND DEVELOPMENT

History of Tenure and Development Until 1933

"In that country which lies around the headwaters of the Gila River I was reared. This range was our fatherland; among these mountains our wigwams were hidden; the scattered valleys contained our fields; the boundless prairies, stretching away on every side, were our pastures; the rocky caverns were our burying places."--Geronimo. [1]

Not a single map records an Apache name for any place on the headwaters of the Gila River, which for at least 250 years was their domain: these names were lost when the land was lost. Apache words for the narrow beautiful place now called Cliff Dweller Canyon are no longer remembered, and the Apache presence is recorded only by a pictograph, drawn in characteristic thin black lines, a few sherds of pottery lying on two ledges, and a burial that has been vandalized. [2] These meager, even melancholic, artifacts give not the slightest hint of the fierce dominion Apaches once wielded over the Spanish borderlands, raiding throughout what is now New Mexico, Arizona, Chihuahua, and Sonora.

The word Apache appears to be a Spanish corruption of the Zuni word Apachu that means enemy and that reveals an early local assessment of these Athapaskan-speaking hunters who had drifted down the continent from what is now the interior of Alaska and northwestern Canada. [3] The duration of this migration is debated, but linguistic studies suggest that the Apaches arrived in the American Southwest around A.D.1400 although there is no archeological evidence to confirm this date. [4] The first historical reference to a people that may have been Apache occurs in the journals of Pedro de Castenada, who accompanied Coronado on his expedition up the Rio Grande in 1540, searching for the seven golden cities of Cibola. [5]

In 1628, while ministering in San Antonio de la Senacu, not far from the present Bosque del Apache Wildlife Refuge, the traveling Franciscan cleric Fray Alonso de Benavides encountered a few visitors whom he specifically identified as Apaches del Xila from west of the Rio del Norte (Rio Grande). [6] The name of these people eventually appeared on a map published in 1650 by Nicolas Sanson d'Abbeville and with a slight drift to the south remained on maps for the next two hundred years. [7] These people and Apaches in general, according to Alonso de Benavides, were a fierce people of superior intelligence with a marked aversion to lying, and there were a lot of them, enough to completely surround New Mexico and to commonly field armies of 30,000. Undoubtedly the Franciscan was wrong about the numbers, but the error probably reflects local concern about Apache potential for havoc.

Twelve years after the Great Pueblo Revolt in 1680, Gila Apaches were raiding Nuevo Vizcaya (present-day Chihuahua and Durango) from the north, beginning centuries of conflict. [8] These raids could be devastating. In the years 1771-1776, for example, 1,674 Spaniards were killed, 154 were captured, 100 ranches were abandoned, and 68,000 livestock animals were stolen. [9] Large retaliatory expeditions were launched into the headwaters of the Gila by the Spanish military, starting in 1747 [10] and continuing at intervals almost for the next 40 years, but these expeditions were little deterrence to a people that dispersed quickly in the mountains, lived off the land, and favored guerrilla tactics.

Despite hostilities, some Gila Apaches made occasional peaceful visits to the Spanish frontier settlements. [11] These visits suggest the curious nature of conflict waged by a culture of roving, loosely affiliated bands that raided for booty, revenge, or personal status and not for conquest: an Apache band could be raiding one settlement and at peace and trading with another. Stolen livestock was the most common Apache trade commodity, and the preferred coin of exchange was liquor and arms. [12] Naturally, these trades could be volatile, but they were sufficiently lucrative that dread Apaches who came to sell horses could for the occasion be eagerly received. The ambiguities of the Apache system of conflict and intermittent or partial peace endlessly complicated, confused, and embittered relations between Apaches on the one hand and Spaniards, Mexicans, and finally Americans on the other.

Although retaliatory expeditions by the Spanish military were largely failures, they did provide opportunities to explore Apacheria. In 1756 and the following year as well, Father Bartolome Saenz accompanied two military forays around the upper Gila River, and he reported on the country to his Jesuit superior in Mexico City, noting good mission sites, commenting on the biota, and making observations about the Apache way of life. [13] Along the Gila at Todos Santos (near the present town of Gila), he also observed pueblo sites, which he correctly inferred to be ancient. Saenz was the first man to record the presence of prehistoric ruins on the upper Gila River. Narrow geography and boulder-strewn water discouraged the mounted expedition from ascending the river past Turkey Creek to the more remote country where Gila Cliff Dwellings lay.

Apaches blocked northern expansion by the Spanish Empire, and by the last decades of the eighteenth century the Spaniards tacitly acquiesced to this state of affairs. In 1786, Bernardo de Galvez, the new viceroy of Mexico and a former campaigner against Apaches, advocated a new approach to peace on the frontier: regular rations for good behavior by Apaches, vigorous and timely punishment for hostile acts, and a diplomacy calculated to quietly disrupt Native American alliances. [14] By the 1790s some Gila Apaches began to settle on reserves around frontier presidios like Janos, and for the next forty years raiding subsided into an uneasy peace. Even unpacified bands ranging on the headwaters of the Gila River more or less respected the accommodation. [15]

After independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico continued the same Apache policies. The new country radically changed another border policy, however, welcoming previously proscribed trade with Americans, and long ox-drawn caravans between Independence, Missouri, and Santa Fe soon began wearing ruts into the prairie. With the traders came fur-trappers, pursuing beaver in the untapped streams and tributaries of the Rio Grande, the Gila, and the Colorado.

Among the first on the Gila was a party of trappers that included Sylvester Pattie and his son James Ohio Pattie. [16] In 1825 the Americans stopped for one night at the Santa Rita mines, a fortified outpost built in 1804 to exploit well-known copper deposits. [17] On the Gila River the trapping party split up. Young Pattie and a companion ascended the river "sometimes on our hands and knees, through a thick tangle of grape-vines and under-brush" in dread of bears. [18] They passed the Gila Hot Springs, clambering finally two days along the West Fork before crossing over to the Middle Fork and descending the river to where Sylvester Pattie waited. If he saw cliff dwellings, James Ohio Pattie did not record them in his journal, but he did observe that there were not "beaver enough to recompense us for our trouble." [19]

A year later, four different bands of American trappers, numbering almost 100 men, also launched expeditions on the Gila River, [20] and until 1838, when the mines were abandoned because of flooding shafts and renewed Apache hostility, [21] Santa Rita became a well-known stop for men like Bill Williams, Michael Robidoux, Ewing Young, Kit Carson, and James Kirker. These trappers, who usually travelled in large groups, were intent on snaring beaver and watching for Apaches, and there is no record that they noticed prehistoric ruins.

In 1831, after 40 or so years of relative peace, the Mexican government ended the regular supply of rations to Apaches--as an economy--and raiding recommenced in earnest. [22] Despite a brief peace negotiated at Santa Rita in 1832, events spiraled into increasing viciousness, culminating with Sonora's renewed offer in 1835 of bounties for Apache scalps. A year after the abandonment of Santa Rita in 1838, the state of Chihuahua also started a bounty on scalps and contracted with James Kirker, who eventually earned 25,000 pesos on this contract and later claimed to have killed 487 Apaches during his entire career. [23] An account by George Ruxton who was traveling through Chihuahua in 1845 describes the celebration of a Kirker victory: "...with scalps carried on poles, Kirker's party entered Chihuahua [city]--in procession, headed by the governor and priests, with bands of music escorting them in triumph to the town." [24] The Apaches, of course, had their own program of revenge and counter-revenge, and the country drained by the headwaters of the Gila River, became an excellent place to avoid.

American soldiers entered this bloody scene in 1846, during the Mexican-American War. In October of that year, Kit Carson guided Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny and his troops through the Mimbres Mountains on their way to complete the conquest of California. Accompanying Kearny was Lt. William H. Emory, who in 1844 had constructed--often from inaccurate sources--a master map of the Southwest for the Army Topographical Engineers. [25] Emory was now able to survey with instruments the path of Kearny's expedition, observations that contributed to his development of another map, which became the standard reference for years. This map was published first in 1851 with the bold words Unexplored Territory across a void on the paper that corresponded to the headwaters of the Gila. [26]

Reporting on his work under Kearny, Lieutenant Emory also included some observations about the ruins at Pecos, Casa Grande on the lower Gila, and other sites along the same river, beginning "almost singlehandedly...the study of Southwestern archaeology." [27]

At the close of the Mexican-American War, under terms of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico ceded nearly half its territory to the United States, including the unpacified lands of Apacheria that contained Gila Cliff Dwellings. The discovery of gold that same year in California encouraged men to travel across the southern edge of the Apache lands, but it was acknowledged "exceedingly hazardous for any but large parties to attempt to pass through their country...." [28]

Over the next ten years, gradual and cautious encroachment by Americans only tattered the edges of Apacheria, and a moderate peace was negotiated. In 1860, however, a gold strike at Pinos Altos sent 700 miners swarming into mountains above Santa Rita, and the peace unraveled in a series of reprisals for stolen stock, dead Apaches, and the egregious public whipping of Mangas Coloradas, a leader of legendary ferocity. The advent of the Civil War, which preoccupied the western garrisons and siphoned troops to the east, and the cessation of the Butterfield Overland Stage line emboldened the Apaches, who drove the settlers out of the Mimbres Valley and effectively closed the mines at Pinos Altos and around Santa Rita. In 1862, following the expulsion of Confederate forces from New Mexico, Brevet Brig. Gen. James Henry Carleton launched a campaign of extermination against the Apaches that lasted beyond his own transfer to Texas in late 1866. [29]

Eventually the Apaches tired. Mangas Colorado was killed under a white flag, and by 1870 even the notorious but aging Cochise was negotiating for peace with the observation that "although [his people] had killed many whites, they had lost many braves so that now he had more women and children to provide for than with a war he could protect, that he desired peace, would talk straight...." [30] The site of these negotiations was Ojo Caliente, on the east side of the Black Range and just upstream from Canada Alamosa, a Mexican settlement and an outpost of Fort MacRae. [31] Ojo Caliente quickly evolved as an informal reservation, and within a year 1,000 Apaches were drawing rations there. [32] In the mid-1850s American authorities had sought to establish reservations for reluctant Apaches on the Mimbres River, and plans in 1860 to set aside 225 square miles around Santa Lucia and the Gila River had dissipated in the hot winds of war. In 1870, the year silver was struck west of Santa Rita, the development of suitable reservations for the Apaches became policy, and the Southwest was made many times safer for settlers--at the expense of Apache rights.

Canada Alamosa was only briefly a reservation, in part because Cochise refused to settle there. In 1872, he received a reservation in the Chiricahua Mountains, and the Mimbrenos were allotted a reservation along the Tularosa River, in unsettled country and far from the whiskey traders at Canada Alamosa. Disliked by the Mimbrenos and expensive to supply from the Rio Grande, Fort Tularosa was closed in 1874, and the Apaches were moved back to Ojo Caliente. Shortly afterwards, the United States government began a policy of closing smaller reservations in order to concentrate Apaches in one place. Within three years all Apaches west of the Rio Grande had been moved to the low country around San Carlos, Arizona.

In September 1877, however, Victorio, a powerful and discontented Mimbreno leader, stole horses from White Mountain Apaches and fled with his band towards the malpais below Fort Wingate. Although he surrendered shortly afterwards, Victorio refused to return to San Carlos, and his rebellion inaugurated nearly a decade of breakouts from that notorious reservation, deadly raids by broncho or "unpacified" Apaches out of Mexico, and relentless military maneuvers of pursuit. In 1880, Victorio was killed in Mexico, but as late as 1885, despite encirclement by mining and farming communities, the Gila headwaters were still remote enough to hide a few non-reservation Indians, who discouraged settlers.

Discovery

The record of archeological discovery on the Gila headwaters is the product of two movements in American exploration, one scientific and the other vernacular. Shortly after the Civil War, the government renewed its support for scientific expeditions to inventory the unknown resources of the American West and to map the country. By the 1870s four of these field surveys were underway, led by professional men who collaborated with the great natural scientists of the age to make important discoveries in geography, geology, biology, paleontology, and archeology. Private scientific organizations supplemented these activities. At the same time, the western frontier continued to lure men and women with visions of free land, adventure, and gold, a demographic movement so important in the nineteenth century that Frederick Jackson Turner--in a famous and still influential essay presented in 1893--attributed to it the creation of America's national character and even of American democracy. In southwestern New Mexico, during the 1870s, the relocation of wandering and marauding Apache bands to reservations opened "new" country to both kinds of discovery, although a recurring threat of renegades made the explorers cautious.

Wheeler Survey

The first scientific description of a prehistoric pueblo ruin on the upper Gila River was written by Henry Wetherbee Henshaw, a self-taught ornithologist, who served from 1872 to 1879 as a naturalist and field collector with Lt. George Montague Wheeler's Geographical Surveys of the Territories of the United States West of the 100th Meridian. [33] In the summer of 1874, Henshaw traversed the Gila country just as the reservation on the Tularosa River was closing down and the Apaches were being transferred back to Ojo Caliente on the east side of the Black Range. Because Apaches had killed a member of the survey several years earlier in a famous incident west of Wickenburg, Arizona, [34] Wheeler required each of his staff to each carry a revolver, a cumbersome precaution that Henshaw found worse than useless since these guns accidentally killed one member of the survey and disabled another. Although a lot of disgruntled Apaches, still "somewhat in their primitive state," were about, the ornithologist apparently did not see any on the Gila headwaters.

Eight miles from the mouth of Diamond Creek, an early name for the West Fork of the Gila River, Henshaw and a companion recorded only as Howell saw and explored the two-room cliff dwelling that is known today as Three-Mile Ruin. The floor was covered two feet deep in rat droppings. More interesting was a large pile of broken bows and more than 1,000 reed arrows, at least one with an obsidian point still affixed. Heavy stones had been placed on the artifacts, Henshaw observed. A search for skeletons in the floor was quickly given up for want of something better than hands and sticks with which to dig, and after taking some measurements, the two men left, rarely being able to spend more than a day or two at any single locality because of the survey's enormous scope.

The discovery was incidental to most of Henshaw's work this field season, which he spent primarily in southern Arizona shooting birds with a breech-loading shotgun and dissecting them on his saddle. In his field report, published in 1875, Henshaw did include a description of his archeological find, however, and the description was included in the last volume of Lieutenant Wheeler's definitive geographical report, which was published in seven volumes in 1889. [35]

Also during the 1874 field season, another party of scientists attached to the Wheeler survey, one that included the famous paleontologist Edward D. Cope, was exploring Anasazi ruins along the San Juan River. The same year, under the auspices of the Hayden Survey--which was sponsored by the Department of the Interior--William H. Jackson and his photographic crew were hauling large-format cameras up the cliffs of Mancos Canyon in Colorado to capture the first views of the numerous cliff dwellings along the still undiscovered edge of Mesa Verde. Altogether it was an auspicious year for American archeology, foreshadowing a scientific--and popular--interest that grew very quickly over the next few years.

Jackson's large black-and-white photographs of cliff dwellings and models that he made elicited broad popular interest when they were displayed at the Centennial Exhibition that opened in Philadelphia on May 10, 1876. [36] Not long afterwards, scientific interest in archeology was invigorated by the appearance of the American Antiquarian magazine and the founding of several important societies, including the anthropology section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Archaeological Institute of America, and the Anthropological Society of Washington. In 1879, John Wesley Powell, leader of a third major scientific survey of the West--also sponsored by the Department of the Interior--established the Bureau of Ethnology, incorporating it as an arm of the Smithsonian Institution. When the four western surveys were combined the same year into the United States Geological Survey, Powell retained his position as chief of the Bureau of Ethnology and laid in the coming years "the empirical foundations of archaeology in the United States." [37]

Henry Wetherbee Henshaw joined the Bureau in 1879, working as an ethnologist and later as editor of the American Anthropologist, which was founded in 1888.

Prospectors

The first known visitor to Gila Cliff Dwellings was Henry B. Ailman, an early emigrant to southwestern New Mexico whose "only hope for success lay in finding something rich sticking out of the ground." In the summer of 1878, already prosperous and the co-owner of the Naiad Queen silver mine in Georgetown, [38] Ailman found his name along with those of several friends on a jury list. To avoid serving they hastily organized a prospecting trip to the headwaters of the Gila River. At this time the bands of Loco and Victorio, which had fled the San Carlos Reservation the previous September, were on their best behavior, waiting anxiously in Ojo Caliente for a decision about their fate. The prospectors saw no Apaches.

Below is Ailman's account of the trip thirty miles from any settlement:

Following the west or larger [creek] up two or three miles, we came upon a specimen of an old Cliff Dweller's village situated, as was their custom, in a crevice where there was good protection afforded by a wide, overhead ledge of projecting rock. In this case, from floor to roof was about eight or nine feet. The walls were of small, flat stones laid in common mud, with no door or window frames. The walls lacked twenty inches connecting with the roof, to give the smoke a chance to escape. They had fireplaces in the center of the apartments.

In searching for relics, the only thing we could find was corncobs, very small, four to five inches long, and only in thickness like your largest finger. A fair sample of these I took with me. This dwelling was about two hundred feet up a steep hill from the creek. We concluded that they selected such sites for protection. Needless to say, Miss Virginia [soon to be his wife] got the corncobs.... [39]

The next season, Ailman wrote, another party from Georgetown visited the same ruins and, beneath a loose stone, found the desiccated body of an infant, which the explorers believed to be prehistoric. A friend of Ailman's eventually photographed the body, and years later--long after he had sold his mine, lost his fortune, and moved to California--he still had the picture. Apparently he also had some familiarity with the construction of cliff dwellings, a knowledge implied by his words "as was their custom." It is impossible to say whether this knowledge was contemporary with his trip or retrospective erudition.

Bandelier

A scientific description of the cliff dwellings that Ailman visited was not made until the winter of 1883-84, when Adolph F. Bandelier spent a few days on the headwaters of the Gila. The son of a prosperous Illinois banker who had emigrated from Switzerland, Bandelier developed an early interest in Mexico and the American Southwest, and through family connections and a series of scholarly monographs he managed to attract the attention of Henry Lewis Morgan, author of the seminal book Ancient Society, president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the foremost anthropologist of his time. [40]

In 1879, Morgan had been asked by the newly organized Archaeological Institute of America to develop a plan for research in the American field, and in 1880 his paper "Study of the Houses of American Aborigines" was included in the society's first annual report. The paper urged the scientific exploration of ruins in the American Southwest and in Central America. Morgan privately urged the executive committee of the society to appoint Bandelier to conduct special research in New Mexico. With an annual stipend of $1,200, Bandelier arrived in Santa Fe in 1880, and for the next five years traveled through New Mexico, Arizona, and Mexico visiting pueblos and exploring hundreds of ruins. His Final Report of Investigations among the Indians of the Southwestern United States, Carried on Mainly in the Years from 1880 to 1885 was published by the Archaeological Institute in two parts, Part I in 1890 and Part II in 1892.

On January 2, 1884, after spending a few days in the Mimbres Valley talking with settlers and exploring ruins, Bandelier departed alone and on foot for the headwaters of the Gila River, where he had heard there were sandstone cliffhouses. At the Gila Hot Springs, he was received by Niels Nelson, a Danish immigrant who made a house available to the explorer, providing him with a bed and even board. The country that had been empty when Ailman visited five years earlier was quickly being settled. In fact Ailman himself now had a ranch near the head of the Sapillo trail into the Gila.

Bandelier's journal entry for January 5 reveals that a romantic sense of place accompanied the scientist's meticulous attention to topography and archeology.

The tops of the high mesas of the Divide are volcanic, making a horrible trail. The mouth of the Sapillo is about 20 miles west of here, and is a deep canon; so is the whole course of the Gila for nearly 40 miles west and high up to the source which is 40 miles northeast from here. There is no snow visible on any mountain, and the tall grass has its stalks still green. The Rio Gilita [East Fork] empties into the Gila a mile south of the Ojo Caliente. All these tributaries flow in deep stately canons, very narrow and grand, but there is vegetation everywhere. On the whole it is a beautiful spot. The hot springs are right opposite, on the banks, oozing out of the declivity. Some of them steam very strongly....

Started for the caves about 8:30 A.M. The valley winds around, past the springs, to the west, and then forms a bottom scarcely a half mile wide, heavily timbered with pines and cottonwood, also oak, which extends, accidently wandering, and leaving very fertile bottoms, all timbered along the river, for nearly four miles. These bottoms were originally timbered, and there are cleared spaces where Mr. Williams and Mr. Rogers [sic] have their ranches. The river, beyond the latter runs near to the West side and the mountains are picturesque vertical craigs. [41]

The caves were in a thickly-wooded side canyon, sheltered beneath an overhanging bluff that protected the prehistoric dwellings from weather. "As a place of concealment," Bandelier observed, the site was also well-chosen, protecting the inhabitants from observation and direct assault, as well. The location's major drawback, he conceded, was the facility with which an enemy could deprive access to water that flowed 100 feet below.

Bandelier noted in his journals that some of the dwellings had been constructed without roofs, a fact that he attributed to the mild climate and the perfect shelter of the caves. Other rooms had roofs that had been destroyed with fire, reportedly by Apaches. Aside from a lot of corn cobs, he also noted, there were few prehistoric remains left on the site--very little pottery and none of the stone axes that others had apparently found in abundance.

After recording some architectural dimensions, Bandelier hobbled out of the ruins on a very sore foot, returning to his lodgings where he spent a painful and lonely night. It was his wedding anniversary. Over the next few days, Bandelier explored the hills around Nelson's house, noting and drawing small ruins, including a pueblo site that is the TJ site. [42]

|

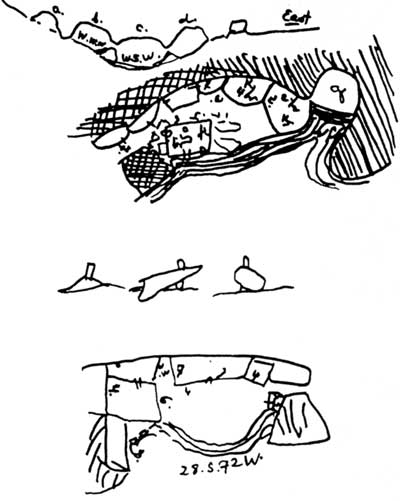

| Sketches of the Gila cliff dwellings that Bandelier made in his notebooks, in January 1884. These mnemonic artifacts are the first representations of this prehistoric architecture and were later reproduced with greater draftsmanship and more detail in his Final Report of Investigations among the Indians of the Southwestern United States, Part II. |

The detail of Bandelier's journal entries and the unrevised immediacy of their style--almost stream-of-consciousness--give an unchallengeable authority to his observations: in early 1884 there were very few artifacts in Gila Cliff Dwellings, a fact he attributes to rifling. Indeed, a few days later on his way back to the Mimbres, he visited a man who showed him "a fine collection of sandals, about seven pieces, which he dug out of the cliffhouses on the Gila, also a ring for carrying water, and a piece of pita wound around with rabbit skin, evidently for a mantle similar to that made and worn by the Moqui [Hopi]!" [43] It is also clear from the journals that many people knew about the Gila cliff dwellings by 1884. Bandelier heard about the site from several informants in the Mimbres Valley and along the Sapillo and also from the settlers around the Gila Hot Springs, at least three of whom he mentioned by name. The first survey of the township, completed in the fall of the same year, also locates the ruins.

As Bandelier rode on a burro back to the Mimbres Valley, the bands of Nachez, Chato, Mangas, and Geronimo were slowly straggling into San Carlos from the Sierra Madre in Mexico as they had agreed after their surrender to Brig. Gen. George Crook in May 1883. Bandelier--who "traveled armed only with a stick a meter long and graduated for measuring ruins" and who had once escaped an encounter with raiding Apaches by feigning insanity--saw no Indians.

McKenna

Another early visitor to Gila Cliff Dwellings was James A. McKenna, a miner from a silver camp in the Black Range, who suffered in 1883 "from a touch of lead poisoning and decided to go with a party of miners and muckers for a few baths in the Gila Hot Springs." [44] After three weeks of bathing, hunting, and fishing on the headwaters of the Gila, he returned to Kingston, settled his affairs and filed a homestead claim on 160 acres of government land close to the hot springs. In the summer of 1884, by his own reckoning, McKenna visited the cliff dwellings with his friend Jason Baxter.

They explored the ruins in four caves, noting especially the solidity of construction. Still intact were the roofs, which were formed of pine beams covered with twigs and grasses and a layer of adobe plaster, and even the floors were in good condition, with adobe mortar sealing any cracks. Within the ruins, McKenna found many "stone hammers and war axes," turquoise beads, and ollas painted with images of bear, elk and deer, as well as other designs.

In addition, he found a "perfect mummy" with cottonwood fiber woven around it.

The sex signs had either decayed or been removed, but all who saw the mummy believed it to be the remains of a female. The length of the figure was about eighteen inches. It lay with knees drawn up and the palms of the hands covering the face. The features were like those of a Chinese child, with high cheek bones and coarse, dark hair. The age of the child at the time of death was thought to be two years. The body was kept for weeks in the show window of a store in Silver City. [45]

This relic soon afterwards disappeared when it was lent to a man representing himself as an agent of the Smithsonian Institution. McKenna later opined in his autobiography that the body had been sold to a private collector.

One interesting issue in McKenna's account is the comments he made about the roofs: he found them intact while Bandelier found them burned. Since Bandelier's observations are too precise to be mistaken, it is possible that McKenna visited the cliff dwellings before the fire that brought down the roof and therefore earlier than Bandelier--in 1883 and not a year later as suggested by the memoirs, which, after all, were written nearly 50 years after the visit.

Curiously, Bandelier himself implied in his final 1890 report that the roofs were intact, contradicting the more immediate evidence of his journals. [46] Twice in his entry for January 5, Bandelier had written that Apaches had burned the roofs, a repetition that possibly reflects the insistence of his informants and the immediacy in January 1884 of the event. That Apaches would burn the roofs of a cliff dwelling, however, is also curious--unlikely even given the fact that apart from several brief raids around Tombstone and Lordsburg Apache renegades spent most of 1883 on the lam and in another country. [47]

Settlers

McKenna also mentioned finding many grooved stone hammers and war axes, which Bandelier did not see. The scientist did write, however, that many stone axes had been carried off, and this information again must have come from the local settlers, of which McKenna was one. That Ailman failed to see stone tools can perhaps be explained if he collected only from the surface. Bandelier's later report includes both physical and anecdotal evidence of excavation at the cliff dwellings, and as late as the mid-twentieth century axes like those McKenna described were recovered from soil within the ruin. The miner may have dug up axes. At any rate, since McKenna claimed to have recovered a lot of artifacts and to have seen intact roofs, the early despoliation of the Gila Cliff Dwellings might date from around 1883, the same year that the first homestead was patented in the area.

|

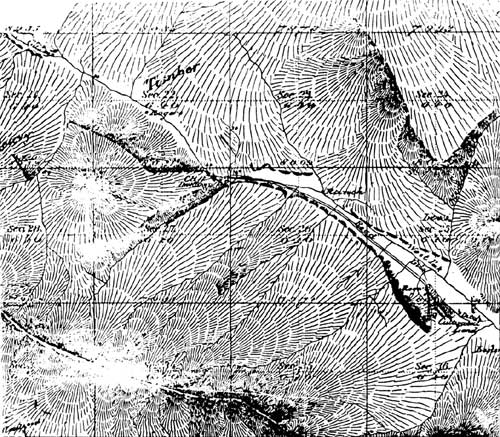

| Sketch from the government survey completed in 1884. The map denotes the location of the Gila cliff dwellings in Section 27, Township 12 South, Range 14 West. Already at least three settlers have located five cabins within two miles of the prehistoric architecture, and a road leads from the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon to cultivated fields. |

After the removal in 1877 of the Mimbres band of Apaches to the San Carlos reservation in Arizona, and despite periodic assaults by renegades, settlers began moving cautiously into the mountains around the Gila headwaters. James B. Huffman, who had settled on 160 acres near the mouth of the Middle Fork, was the first to "prove up" a homestead on the forks of the Gila, receiving his patent in 1883 for land that coincidentally contained the TJ site. [48] The five-years-of-residence requirement places his arrival no later than 1878, possibly after Ailman's visit in July of the same year to the cliff dwellings.

Eighteen eighty-three is the same year that James McKenna filed a homestead on 160 acres not far from the Gila Hot Springs, where he had "boiled out" a touch of lead poisoning not long before with a bunch of miners and muckers from Kingston. Already, according to his memoirs, the hot springs were well-known. The Hill brothers, who were developing the waters, had built bathhouses and a sixteen-mile road from Sapillo Creek to their spa and had twenty-five acres under cultivation, a small herd of cattle, and an adobe house with a good supply of groceries. This building is the same one that sheltered Bandelier. One hundred and sixty acres of land that included these hot springs were ultimately patented by Spencer Hill in 1890. Other local homesteaders known to McKenna in 1883 included Jordan Rodgers, John Lester, a man named "Grudgins" who worked for him, and a Tom Wood who had settled with a wife and six children near the mouth of the East Fork. Farther up the forks of the river and on the mesas were John Lilley, Thomas Prior, Presley Papenoe, and another man named Tom Woods, who was unrelated to the married settler on the East Fork. Country that had been empty five years earlier, when Ailman visited, was filling up fast.

In the government survey of 1884, when the subdivisional lines for T12S R14W were laid out to facilitate homestead claims, Richard Powell, the U.S. deputy surveyor, also noted the location of Gila Cliff Dwellings and the presence of a road that led from the cultivated fields of Rodgers more or less to the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon. Although still remote, the cliff dwellings were increasingly accessible.

McKenna spent two years prospecting and market-hunting game for miners in Silver City, before suddenly abandoning his homestead in the summer of 1885--not long after a desperate escape on the upper West Fork from a band of Apaches, who killed his best friend, Jason Baxter. Sixteen other people in southwestern New Mexico were also killed in May. Late in the fall of the same year, Papenoe, Lilly, and Prior were killed in the Mogollons, along with 35 others between the Rio Grande and the San Pedro rivers. The killers were a band of nine warriors, who rode out of the Sierra Madre on a 1,200 mile raid led by Josanie, a Mimbreno and a younger brother to Chihuahua. Josanie's furious raid marked the last Apache attack in New Mexico: three months later, in April, captive Chiricahua and Mimbreno bands began their long trip in freight cars to Florida, and their broncho relatives followed after their surrender in September to Brig. Gen. Nelson Miles, who had ferreted the last resisters out of the Sierra Madre. [49]

Violence on the headwaters of the Gila did not end with the exile of the Apaches, however. In 1892, the young son of Tom Woods who ranched far up the Middle Fork and a Mexican companion were mysteriously murdered while asleep in their camp about two miles above the Grudgings' cabin on the West Fork. [50] A year later, William Grudgings, who had worked for McKenna years before, was shot and killed. James B. Hoffman (Huffman) claimed to have witnessed the assault and swore out a warrant of arrest for Tom Woods, stating that the accused, disguised but still identifiable under a headdress of weeds, had ambushed Grudgings. [51] Shortly afterwards, at his arraignment in Mogollon, Woods acknowledged that he had indeed cut down Grudgings because the man had killed his son. [52]

In a curious turn of events, Woods was released in a nearby canyon by a citizen, who had somehow gained custody of the accused and who the same night went on to kill a former partner in a wood contract. Woods escaped in the confusion. [53] Years later, Woods claimed to have spent the next two years hunting down William Grudgings' brother, Tom. One day, emerging with a greeting and a leveled gun from a canebrake in Louisiana, Woods shot Grudgings, who was about to cross a river in a canoe. [54]

Woods himself crossed into folklore. There are several variants to the Woods-Grudgings feud that favor both sides and that involve death by fast draw, a rifle shot in the back, or an axe. Although Woods eventually stood trial and was acquitted for William Grudgings' death, the trial papers have been lost. The only hard and uncontested facts of the case are carved in stone:

William

Grudgings

WAYLAID AND

MURDERED

BY

Tom Woods

OCTOBER 8, 1893

AGE

37

YEARS 8 MONTHS

The foot of this grave lies just outside the northern boundary of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Beside this tombstone is the grave of William B. Huffman, the first settler on the forks of the Gila, who was killed not long after the Woods-Grudgings feud by his neighbor Jordan Rodgers, concluding in this way a disagreement about cattle ranges. Rodgers was also acquitted. [55]

Not long after Huffman was killed, the settled land around the forks of the Gila began to change hands--and character. C. A. Burdick, who owned the large O-Bar-O outfit a little farther north, bought out Lester, Rodgers, another man named Clifford, and the heirs of Huffman, consolidating their marginal homesteads under the TJ brand. [56] Shortly afterwards, John Converse, a Princeton graduate and the son of a wealthy Philadelphia locomotive builder, bought the TJ Ranch, reportedly for $80,000. [57] Included in Converse's vision of the West was a string of polo ponies, which he reportedly exercised on the site of the TJ Ruin. A little farther east, along the streams feeding the East Fork, a friend of Converse's who was also a Philadelphian and a graduate of Princeton to boot, Hugh Hodge, bought up patented land from debt-ridden homesteaders to build the Diamond Bar Ranch. Eventually he acquired the old Tom Wood homestead on the East Fork, as well. In 1899, Thomas Lyons of the huge LC Ranch and Cattle Company bought a 160-acre patented homestead just upstream from the Wood place, where he built for $50,000 a hunting lodge with accommodations for 30 or 40 guests. [58] In just over a decade, the small hard-scrabble homesteads around the cliff dwellings were yielding to the interests of wealthy men.

Unhappily, the cattle these men brought to the Gila headwaters in the years between 1885 and 1895 severely damaged the area's range and riparian ecologies. The thick tangles of growth noted by Pattie and the lush beautiful vegetation that Bandelier had seen were eaten and trampled until there was "scarcely a vestige of grass for miles" in 1927. [59] In the river where trout could formerly and easily be taken, "there [was] a sluggish and unshaded stream, filled from bank to bank with flood waters during the summer rainy season." [60]

Meanwhile during the 1890s, at the Gila Hot Springs, the Hill brothers were serving game, fish, and wine to parties that came for the baths--"vapor, Turkish, Russian, hot, cold or temperature as one may prefer." [61] Although the resort was small, life was surprisingly gay with the grounds laid out for games, dances held at night, and the society reported on by the Silver City Enterprise. Fishing trips were occasionally organized to go up the West Fork, where the ladies of at least one group decorated with wildflowers the grave of Jason Baxter, who had been killed there by Apaches only six years earlier. [62]

Another place familiar to the Hill brothers was Cliff Dweller Canyon, where parties were entertained with lunches among the cave ruins. [63] Several years earlier, in 1889, the brothers had also found a burial at the cliff dwellings: the desiccated body of a child who appeared to be about four years old. Wrapped in cloths and bound to a piece of wood, the body was well preserved with still perfect fingernails, intact teeth, and soft black hair. Reportedly, the body was sent to the Smithsonian despite efforts of the Silver City Enterprise to purchase the relic. [64]

Gila River Forest Reserve

In March 1899, President William McKinley withdrew from settlement the Gila River Forest Reserve, the sixth such reservation of forested public land in the Southwest and the second in New Mexico. [65] On the forks of the Gila, this reservation effectively limited patented land around the cliff dwellings to the TJ Ranch, the Gila Hot Springs Ranch, Lyons Lodge, and the XSX Ranch--Grudgings' cabin was returned to the public domain in 1901 by quit-claim. Two of these four holdings catered specifically to people seeking recreation, people who could be entertained by visits to cliff ruins.

A year after the withdrawal, M. Belden arrived in Silver City charged with management of the forest reserve, a task that included, according to the Silver City Enterprise, preserving the cliff dwellings from vandalism. [66] Protection could only be incidental, however, to the forest supervisor's more central task of controlling fires and surveying and managing the timber. An inventory of the Gila Forest Reserve conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey in 1903 and published in 1905 as Forest Conditions In The Gila River Forest Reserve, New Mexico did not even mention the cliff dwellings, for example. [67] The author did observe, however, the popularity of the Gila Hot Springs resort and "in consequence a small settlement of Mexicans...a short distance above the springs." [68]

Antiquities Act

Protection throughout the Southwest of ruins like Gila Cliff Dwellings was complicated by the fact that no laws specifically prohibited the collection of prehistoric artifacts. On public lands, including the forest reserves, trespass charges were the primary instrument of punishing vandals, [69] but surveillance of the sites was incidental to the regular duties of the employees of the Interior and Agriculture departments.

By the turn of the century, vandalism of Southwestern archeological sites was reaching alarming proportions. As early as the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876, professional collectors had been commissioned to provide artifacts for the display. [70] In the following years, people without academic qualifications began excavating, as well, and selling the recovered artifacts. Often, these excavations entailed the destruction of architecture as well as stratigraphy, with walls being pushed down in the search for buried pots, tools--and mummies, which seemed to have especially popular appeal. Particularly rankling to scientists were the activities of Richard Wetherill, who excavated at Mesa Verde, Grand Gulch, and later Chaco Canyon, where he filed a homestead claim on land that included Pueblo Bonito, the largest Pre-Columbian building north of Mexico. [71]

On the upper Gila River and along the Mimbres drainage, despoliation in 1900 was still principally the product of ignorance, consisting of nearly ubiquitous "potting" by the curious, the carting off of stones from the prehistoric architecture for reuse on contemporary structures, and damage by livestock. In 1884, in addition to noting the "rifled" condition of Gila Cliff Dwellings and the purported Apache vandalism, Bandelier noticed black matter that looked suspiciously like manure, an ugly observation that foreshadowed trouble for unfenced sites. The withdrawal 15 years later of the Gila Forest Reserve protected the cliff dwellings from some of the more heinous vandalisms like that of a cliff dwelling on the Blue River, where a settler kept his goats corralled within ruins on his patented land. [72] And, of course, large-scale destruction of architectural sites in southwestern New Mexico did not really begin in greedy earnest until after 1914, when E. D. Osborne of Deming sold his first collection of Mimbres pots to Dr. Jesse Walter Fewkes of the National Museum and the cash value of the local prehistory was established. [73]

In 1900, the same year that Belden arrived on the Gila River Forest Reserve, a bill was introduced into Congress that authorized the preservation by law and the regulation of prehistoric sites and natural formations of scientific and scenic interest, setting these places aside as parks or reservations. Although no action was taken on this bill, Congress wrestled for the next five years with the language, intent, and the technicalities of responsibility in similar proposed legislation, finally passing in June 1906 a bill introduced by Rep. John F. Lacey of Iowa, a long-time conservationist and chairman of the House Public Lands Committee. [74]

Under the Act for the Preservation of Antiquities, also known as the Antiquities Act, the president was authorized to set aside by executive order land that contained prehistoric and historic ruins and "other objects of scientific interest." These reservations were called national monuments and were to be managed by the Interior, Agriculture, and War departments, depending on which agency had controlled a particular site before it was withdrawn.

Hewett

Instrumental in drafting the Antiquities Act was Professor Edgar Lee Hewett, formerly president of the Normal University at Las Vegas and one of the founders of the Archaeological Society of New Mexico. [75] He was an early and ardent advocate of archeological preservation, and the investigations that led to the curtailment of Richard Wetherill's excavations in Chaco Canyon in 1901 stemmed from complaints by Hewett and his Archaeological Society. Hewett wrote on New Mexican archeology for the 1901 and 1902 Reports of the Governor of New Mexico to the Secretary of the Interior and published studies on the ruins at Pecos and later the ruins on the Pajarito plateau in the American Anthropologist.

In 1902 Hewett guided Representative Lacey through the ruins on the Pajarito, which strengthened the congressman's resolve to protect Southwestern archeology. When Hewett's university contract was not renewed in 1903, he decided to pursue his archeological interests on a full-time basis and departed for Switzerland, where he studied archeology at the University of Geneva, proposing a dissertation on the archeology of the American Southwest. In 1904, he was back in the United States working as an assistant ethnologist in the Bureau of American Ethnology, when the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution proposed that Hewett coordinate the various efforts of different organizations and institutions to protect Southwestern ruins.

During and even before the long congressional debate that finally resulted in the Antiquities Act of 1906, the Bureau of American Ethnology had been compiling an archeological map of the United States with an accompanying card catalogue of the various sites. In 1905, Hewett published in the annual report of the Smithsonian Institution "A General View of the Archaeology of the Pueblo Region," a summary of the types and locations of prehistoric pueblos and a prescription for their preservation. Included on his shorter list of sites recommended for permanent preservation were Gila Hot Springs Cliff Dwellings, undescribed but accompanied by a photograph. In 1906, to assist the various departments of government that were charged by the Antiquities Act with preserving prehistoric sites, the Bureau of American Ethnology continued to compile its archeological card catalogue and planned the publication of a series of bulletins "devoted to the fuller presentation of all that is known regarding these antiquities." [76] The next year the Smithsonian published Bulletin 32, a survey by Hewett on the antiquities of the Jemez Plateau, and Bulletin 35, a survey by Dr. Walter Hough of the antiquities of the upper Gila and Salt River valleys. [77] Hough's publication was based in part on an expedition that he had organized in 1905 to visit the San Francisco and Blue rivers and, although he did not visit the Gila headwaters, included the early description by Bandelier of Gila Cliff Dwellings and Henshaw's 1874 description of Three-Mile Ruin. No first-hand archeological work had been done on the headwaters of the Gila for a long time, but the name of the cliff dwellings was being repeated in important places at an important time.

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument

In 1906, President Roosevelt set aside by authority of the Antiquities Act four national monuments: Devil's Tower in Wyoming, Petrified Forest and Montezuma Castle in Arizona, and El Morro in New Mexico. The Southwestern sites had already been withdrawn from settlement by the General Land Office until a way to make their preservation permanent could be found. [78] Meanwhile the Forest Service [79] circulated Forest Order 19 that directed forest supervisors to report on historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of scientific interest located on the forest reserves. [80] In December, Gila Forest Supervisor R. C. McClure reported to the chief forester in Washington, D.C., that although the forest abounded with ruins and "hieroglyphics", the only structure known to him warranting preservation by the national government was the cliff dwellings four miles above the Gila Hot Springs. [81] He observed that the site was exceedingly well-preserved although many artifacts had been carried off since its discovery in the 1870s by hunters and prospectors. With an eye toward commercial threats, he further observed that the area was free of minerals (and hence not in conflict with potential resource use). Finally, he recommended that a half-mile stretch of fence--with a good gate--close off the mouth of Cliff Dweller Canyon and that it be the special duty of the forest ranger to see that the ruins were not despoiled. McClure enclosed a map.

In April 1907, the acting chief forester wrote McClure for clarification about the exact location of the cliff dwellings, requesting "an accurate description of the precise tract which should be withdrawn as a National Monument." [82] The Forest Service had concurred with McClure's recommendations for the cliff dwellings. Whether or not this decision was based solely on the comments of the Gila Forest Supervisor is unknown, but the name Gila Cliff Dwellings cropped up sufficiently in the contemporary scientific literature that anyone seeking further justification for establishing a national monument would find support. [83] On November 16, President Roosevelt by executive proclamation set aside a quarter section of land containing the "Gila Hot Springs Cliff-Houses" as Gila Cliff-Dwellings National Monument.

The 1907 proclamation creating Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument specifically prohibited settlement on the reservation and damage or appropriation of any of its features. Roosevelt's proclamation also stated that the reservation of the monument was "not intended to prevent the use of the lands for forest purposes under the proclamation establishing the Gila National Forest, but so far as the two reservations are consistent they are equally effective." [84] In short, the Forest Service would continue to manage the 160 acres set aside as a monument.

Forest Service Management Of The Gila National Monument

Unfortunately, the designation of a national monument did not automatically make it a priority. In 1916, Hugh Calkins, the Gila forest supervisor, wrote to his district forester that the national monument received "very little attention from the forest service other than keeping it posted with cloth signs." [85] One of the major problems in managing the site was its remoteness. The cliff dwellings were included among the remote sections of the McKinney Park Ranger District, [86] which was operated during the summer from the old Jenks cabin, 17 roadless miles farther up the meanders of the West Fork. In addition, the cabin itself was 25 miles of trail from Gila, the nearest settlement, where the ranger lived in the winter, operating from his house. Other problems were time, money, and staff. The established priorities of the Forest Service were to control fires, manage timber, and regulate grazing.

Nevertheless, in the early years Henry Woodrow, the McKinney district ranger, was able to persuade cowboys from the Heart Bar Ranch, formerly the TJ Ranch, on whose grazing allotment the cliff dwellings lay, to help fence off the archeological site from the cattle that liked to shelter in the caves from harsh storms. [87]

In all fairness, neglect engendered by isolation and short budgets was not just a problem of the Forest Service. To supervise the Montezuma Castle, Petrified Forest, Tumacacori, and Navajo national monuments, for example, the General Land Office appointed one man, whose offices were in Los Angeles in 1913. [88]

A year after the establishment of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, Albert F. Potter in the capacity of acting forester, wrote to all forest officers, asking them to cooperate with the Bureau of American Ethnology's survey of historic and prehistoric sites and places of scientific interest that were located on national forests. [89] He further instructed that such sites were not to be listed under the Homestead Act of June 11, 1906, legislation that reopened to settlement lands formerly closed by the establishment of the forest reserves. Acting Gila Forest Supervisor Frank Andrews wrote back that the only object of historic or scientific interest on the Gila National Forest was the Gila Hot Springs Cliff Houses, which was already protected by proclamation. [90]

Andrews did not agree with McClure that the forest abounded with ruins. Distinguishing significant prehistoric sites was difficult without training, however, and aside from the much earlier and brief work of Bandelier and Henshaw no survey of archeological sites had occurred within the boundaries of the Gila National Forest. Unfortunately, the response given by Andrews foreshadowed official views for almost the next 50 years.

Two years later, Gila Cliff Dwellings made a cameo appearance into the public view. In a September 1910 article, Harper's Weekly noted the growing recreational use of the national forests by people attracted to such wonders as the Grand Canyon National Monument, Glacier National Park, and Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. [91] Accessible only by foot or on horseback, however, the cliff dwellings did not attract many people who could compare the scale of the attractions.

An interesting discovery at the cliff dwellings in 1912 brought the ruins more national attention. Forest Service employees found a burial, already half-disinterred, which they brought to the supervisor's office in order to prevent further vandalism. Forest Supervisor Don Johnston, in a letter to the district office, described the body "as approximately 24 inches in length and apparently fully developed." [92] Johnston also asked that a member of the discovery party, who was conversant with the facts, be permitted to write press notices. Not long afterwards, an article appeared in Sunset magazine, rhapsodizing about a race of dwarfs that had inhabited Gila Cliff Dwellings 8,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age. [93] Beyond describing the little body--grey-haired and with a full set of adult teeth--the author advanced her theory by pointing out those little doorways in the cliff dwellings "that would not admit anything but a dwarf race."

"Zeke," a name the Sunset writer applied to the burial, had been sent to the Smithsonian, and a scientific assessment was eventually published in 1914 in the Smithsonian's Bulletin 87: a child a few months old. [94] The episode would be merely curious except for the fact that on the 1915 Gila National Forest map, under a picture of Gila Cliff Dwellings, there is a paragraph describing for the benefit of travelers those ruins as the former dwelling place of a prehistoric race of dwarfs. [95]

In 1916, new official interest in Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument was finally engendered by the long birth of a new federal bureau, the National Park Service. As far back as 1900, efforts had been made to establish an agency that could manage in a coordinated fashion the growing number of national parks and later of national monuments. Gifford Pinchot, whose vision and influence had essentially "created" the Forest Service, had strongly opposed the establishment of a park bureau in the Department of the Interior, believing that his own bureau in the Department of Agriculture could best manage the national parks. [96] He may also have realized that many future national parks would be carved out of the national forests. Indeed, immediately before the establishment of the Park Service in 1916, Lassen Peak National Monument and nearby Cinder Cone National Monument in California, both originally administered by the Forest Service, were incorporated as the Lassen Volcanic National Park and transferred to Interior. Even after his ouster as chief forester in 1910, Pinchot's views were still influential and were shared by subsequent chief foresters. [97]

As a parks and monuments bureau became increasing inevitable, however, advocates of the Forest Service retrenched, arguing that at least the national monuments then administered by the Department of Agriculture not be transferred and that all new parks created from the national forests not be transferred either. By 1916, only the transfer of the national monuments was being contested, when the assistant forester circulated a letter to the districts, asking essentially what objections might be developed regarding the transfer of the monuments. [98] In June, Hugh G. Calkins, the Gila forest supervisor, reported--as mentioned before--that Gila Cliff Dwellings got very little attention from the Forest Service and added that unless the service received a special appropriation the monument would be better administrated by the Department of the Interior. [99]

|

|

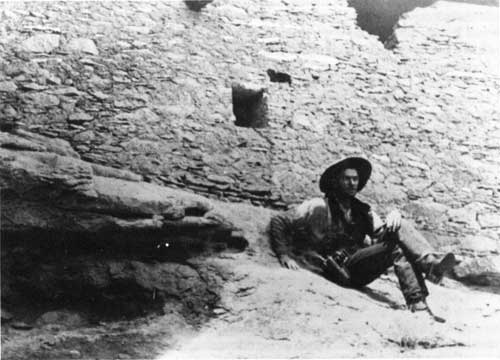

Early visitor to Gila Cliff Dwellings. Alex Thomas photo., 1912 or 1913. |

Also in June, the Washington office staff of the Forest Service, commonly known as the Service Committee, heard a report from Albert F. Potter that urged better management of the national monuments in the forests. [100] Potter, the same man who had instructed forest supervisors to survey their prehistoric assets in 1908, had just returned through the districts and reported that "[we] were not giving some of the smaller national monuments, such as the Cliff Dwellers of the Gila Forest, the proper care and supervision to which they were entitled." [101] Potter recommended that a plan of improvement be worked out for each national monument. His comments and the ensuing discussion are the extent--on record at least--of attention at the Washington level given to the management of the monuments on national forests between the years 1916 and 1933.

When the enabling legislation for the Park Service was signed in August, the monuments in the national forests stayed with the Department of Agriculture. That fall forest supervisors finally developed management plans for the monuments in their respective forests. For the Gila, Supervisor Calkins reported that designated camping sites and shelters were unnecessary at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument since there were few visitors and since those who did visit camped elsewhere for lack of livestock forage. [102] His plan of improvement provided for new cloth posters for posting the boundary, a foot path from the West Fork, a sign warning against defacing the ruins, and most importantly the obliteration of the names visitors had scratched, carved, and otherwise written on the walls of the caves and ruins. In January, Henry Woodrow, the ranger on the McKinney Park District, reported that he had spent a day at the cliff dwellings posting the boundaries and the trail and working on a foot path and that another two days would be needed to finish the trail. [103] He added that the graffiti could be best removed by rubbing them with mud, a task that might take another half of a day.

And so it went. Between 1907 and 1933, when the Park Service assumed responsibility for Gila Cliff Dwellings, the monument lay at the far end of the McKinney Park District and--unbudgeted and unstaffed--at the end of the forest management agenda. Attention was almost always incidental to the other duties of the ranger and his forest guards, but when applied it was competent: the remote and well-sheltered cliff dwellings did not significantly deteriorate. No visitor records were kept, and estimates about the number of visitors varied: Supervisor Johnston, when reporting the discovery of "Zeke" in July of 1912, wrote that many people visited the ruins in that season; four years later, in his management plan, Supervisor Calkins wrote that the ruins were not visited by a large number of people. Undoubtedly, most visitors came from the nearby hostelry at the Gila Hot Springs or from Lyons Lodge and viewed the ruins as part of a day's excursion.

Wilderness

Although a benign neglect characterized Forest Service policies towards the cliff dwellings, another management policy for the Gila National Forest would have a profound effect on the future of the national monument: the establishment of the Gila Wilderness in 1924. The idea of a large roadless area in a national forest was originally proposed by Aldo Leopold, a graduate of the Yale Forestry School who had begun working in the Southwestern District in 1909. [104] An assistant district forester in charge of grazing by 1915, Leopold was also a sportsman with a consuming interest in game management, a nascent field that later made him a national figure. In that same year, Congress passed an Agricultural Appropriations Act that for the first time established recreation as a legitimate use of the multiple-use forest policies, and Leopold was given the task of planning recreation in the Southwestern District. [105] This work primarily consisted of planning campgrounds, plotting subdivisions for summer homes, and developing commercial policies. In 1920, however, in the Journal of Forestry, Leopold proposed something grander: a national hunting ground in a roadless area "big enough to absorb a two-week pack trip."

In 1922, Leopold surveyed possibilities in the Gila National Forest with Supervisor Fred Winn and returned to Albuquerque with a proposal, in the form of a recreational plan, for a roadless or wilderness area of approximately 750,000 acres. Frank Pooler, the district forester, signed the recreational plan on June 3, 1924, thereby designating the first official wilderness in the world. [106]

In the heart of this wilderness lay Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Since the new recreational plan essentially prohibited the construction of new roads through the wilderness, the monument remained isolated at the end of a very rough nineteenth-century wagon trail. The few residents on the Gila forks were permitted to use this unmaintained track, but only trucks with special gearing could manage the terrain. Although grazing was still permitted, logging was proscribed, mining inhibited, and the construction of public recreational facilities prohibited. As a result, the forks of the Gila remained undeveloped, far eddies on a remote stream.

The recreational plan that created the Gila Wilderness was modified in the late 1920s in a way that would again--although only years later--affect Gila Cliff Dwelling National Monument. On the east side of the wilderness, reconstruction began on the North Star Road, an old military trail first built to control Apaches during the Fort Tularosa Reservation period. Pressure to reopen this road by ranchers and logging interests had been resisted until 1929, when a tremendous growth in the population of deer occurred. Fearing a repetition of the Kaibab disaster, where thousands of deer on the north rim of the Grand Canyon had died of starvation, Frank Pooler, on the recommendation of a committee convened to address the problem, authorized the road reconstruction so hunters could better get into the remote country to reduce the herds. [107] The road was completed in 1931. Although Leopold and Winn urged that the road be closed to public use except when necessary, the North Star Road remained open year around, cutting off the Black Range from the rest of the Wilderness.

The same committee of representatives from the Forest Service, the U.S. Biological Survey, the state game department, and the Silver City Game Protective Association that had recommended the reconstruction of the North Star Road also recommended improving the Gila Hot Springs Road as far as the Gila Flats--only half way to the Hot Springs and the cliff dwellings beyond. Eventually this improvement was also made. [108] Although a locked gate at Gila Flats prevented uninvited visitors from continuing on the rough private track that the new owners of Lyons Lodge maintained to the Gila River, this road and the North Star Road set precedents that would embroil Gila Cliff Dwellings in controversy twenty years later. For the time being the national monument remained isolated, however. Only residents on the Gila forks had keys to the locked gate, and the lock stayed until shortly before the end of the Second World War. [109]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

gicl/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 23-Apr-2001