|

Gila Cliff Dwellings

An Administrative History |

|

INTRODUCTION

|

|

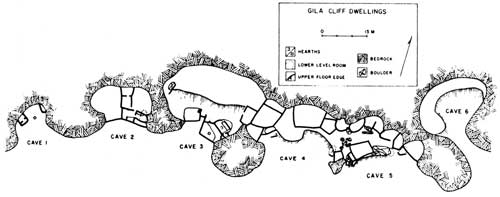

Floor plan of the caves sheltering the Gila cliff dwellings. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Summary: Significance of Cultural Resources

When Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument was established in 1907 to protect the prehistoric architecture known at the time as the Gila Hot Springs Cliff-Houses, there had been little investigation of the local archeology. Furthermore, the general taxonomies of culture were still inadequate for the distinctiveness of these prehistoric remains to be recognized.

Since that time the Mogollon culture has been accepted as a distinct and important prehistoric culture that was endemic to southwestern New Mexico, southeastern Arizona, and adjacent areas of northern Mexico and western Texas. Near the center of this culture area lie the headwaters of the Gila River and Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Since 1955, these headwaters have been recognized as an area of special archeological wealth, with more than 103 prehistoric sites identified within several miles of the West Fork-Middle Fork confluence. In 1962, the original 160-acre monument was nearly tripled in size and is now known to incorporate 45 of these sites, including the TJ Ruin, a open pueblo that contains perhaps 200 rooms.

In the system of national parks, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument is the only unit that contains Mogollon sites. The known prehistoric sites on the monument range from Archaic rock shelters through Early and Late Pit House and Classic Pueblo periods to an Apache [1] grave—a complete 2,000-year sequence of local cultural development, ranging from semi-permanent habitations to large villages with multiple spheres of influence and then to abandonment and later reoccupation of the area by nomads. The archeological resources of the monument may help scientists to trace and understand regional evolutions in subsistence strategies, settlement patterns, social organization, trade networks, and demography.

Although in the center of the Mogollon area, the monument lies on the periphery of the Mimbres branch, a subset of the larger culture that was centered in the Mimbres Valley and that is famous for its painted pottery. At the headwaters of the Gila, Mimbres populations adjoined another more northern branch of the culture. The TJ Ruin, for example, is a Classic Mimbres phase pueblo; the cliff dwellings are Tularosa phase, the product of a prehistoric population that more commonly built near the present town of Reserve. Consequently, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument contains archeological resources that may also help to clarify the relationships between the various cultural branches and to understand the origins and dispersal of cultural innovations.

Finally, with the exception of the cliff dwellings, which had been more or less rifled before the turn of the century, the monument preserves sites that are nearly unique in southwestern New Mexico for their relatively undisturbed nature. An old and increasingly lucrative market in Mimbres pottery has led to the despoliation of 95% of Mimbres sites in the surrounding area. Lamented by professional archeologists since the 1920s, this vandalism continues today, destroying prehistoric architecture and the important context of associated artifacts. In other words, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument preserves an archeological resource that is vanishing rapidly elsewhere.

|

|

The well-preserved architecture of the Gila cliff dwellings dates from

the late thirteenth century A.D. These photographs show the stabilized

ruin from the exterior of Cave 3 and the interior of Cave 4. Photographer—National Park Service. |

Summary: History of Tenure and Development

For centuries, protection of Gila Cliff Dwellings was only the product of geography. Sheltered in six caves, the mud-and-stone architecture avoided the erosion of wind and water that by the 1880s had reduced a nearby mesa-top site to rubble. The remote, deeply incised canyons of the Gila River forks impeded intruders into the area. Even in the thirteenth century this country was isolated, with the cliff dwellings roughly marking the far southeastern edge of the Tularosa phase of the Mogollon culture.

Long after the cliff dwellings had been abandoned, Apaches drifted on to the headwaters of the Gila River, keeping the area additionally and dangerously remote. Evidence reveals that Apaches occasionally entered Cliff Dweller Canyon, but apparently—and for reasons not adequately developed in the anthropological literature—they did not seem inclined to disturb prehistoric pueblo sites. [2] At any rate, they left no trace in Gila Cliff Dwellings, and they largely kept everybody else out until the late 1870s. After the Apaches were expelled from the headwaters of the Gila River—the endemic bands were eventually shipped in freight cars to Florida—rough topography, poor economic prospects, and all the many miles to the nearest town continued to severely limit the number of people who came into the country.

Unfortunately, within six years of the first recorded visit to the ruin in 1878, the site was thoroughly rifled. After 1899, federal policies began to supplement the protection initially provided to the cliff dwellings by geography and Apaches. The establishment of the Gila River Forest Reserve in that year withdrew public land on the headwaters of the Gila from further settlement until 1906, and the designation in 1907 of the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument by presidential proclamation permanently withdrew the archeological site and 160 surrounding acres from private ownership. The proclamation also prohibited damaging or removing prehistoric artifacts.

Without specific funding, however, supervision of the ruin was only the incidental duty of a forest ranger who was seasonally headquartered 17 miles of river trail from the site. Well into the third decade of the twentieth century, protection of Gila Cliff Dwellings would still depend on the site's remote location, an isolation that was augmented in 1924 when a vast area of the surrounding forest was officially designated the Gila Wilderness.

In 1933, as the result of an administrative reorganization, jurisdiction over Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument passed over to the National Park Service, along with all the other national monuments managed either by the Department of Agriculture or the War Department. Briefly, in the last years of that decade, the Park Service sought to establish a national park around the headwaters of the Gila River, with a proposal that included 650,000 acres of the Gila Wilderness and the cliff dwellings. By 1940, the park proposal had been modified, however, and then it was abandoned.

In the same year, after an arduous visit to the remote monument, the Park Service's regional director recommended that Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument be managed as an archeological reserve and that visitation be discouraged. Two years later, a nominal custodian was appointed and the ruins were stabilized, but the larger policy of managing the area as an uninterpreted reserve lasted another 13 years.

In 1955, a draft MISSION 66 prospectus was developed in Region III (later the Southwest Regional Office) that suggested the monument be transferred to a state agency. After Dawson Campbell, the monument's custodian, and visiting archeologists from the Mobile Stabilization Unit of the Park Service pointed out many additional archeological sites in the vicinity, however, the prospectus was revised. New sites and another 273 acres were added to Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument in 1962, increasing its size to the current 533 acres. In the same year, and for a variety of reasons that centered around limitations of the local geography, another 107 acres were withdrawn as a joint administrative site where the Park Service and the Forest Service could build facilities to manage their respective responsibilities.

In early 1963, shortly before the first paved road reached the forks of the Gila River, a full-time ranger was appointed by the Park Service to manage the monument. Over the next 13 years, the cliff dwellings were excavated and stabilized again, and a formal program of interpretation was finally established. Based on a 1964 memorandum of agreement and a master plan developed the same year, a shared physical plant was built on the joint administrative area. Costs were shared between the Forest Service and the Park Service, and the construction included roads, a visitor center, residences, a contact station, and a barn.

In 1975, for reasons of economy, daily management of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument was transferred back to the Forest Service. As specified by the new cooperative agreement that accomplished the transfer, however, the Park Service retains jurisdiction, reimburses for costs of managing the monument, and provides relevant expertise in such areas as interpretation, preservation, and research.

|

|

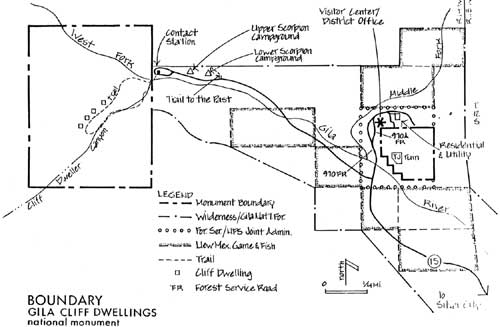

Boundary of Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. (click on map for larger size) |

Summary: Setting

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument is divided into two units that are located in Catron County, the largest county in southwestern New Mexico and the least populated in the state. Specifically, the two units lie in Township 12 South, Range 14 West. The western unit comprises 480 acres, includes the namesake cliff dwellings, and lies in sections 22 and 27. The TJ unit is about one mile farther south. Named for the TJ Ruin, which it encompasses, this unit measures 53 acres, and lies in section 25. The headquarters of the monument, a building that also houses the offices of the Wilderness Ranger District, lies on yet another 107-acre parcel that was withdrawn as a joint-use administrative site and that remains under Forest Service jurisdiction. This parcel is also located in section 25 and is adjacent to the TJ unit.

Geology

The predominant geology of the area stems from volcanic activity in the Oligocene epoch, beginning about 30 million years ago and lasting 20 to 25 million years. Approximately 1,000 to 1,200 feet of ash and other volcanic materials were deposited. The surrounding land then collapsed into the voids created by the volcanic outpourings, resulting in a phenomenon called a caldera. The near ubiquity of rhyolite and basalts reflect this geologic past, and so do hot springs along the river.

As the volcanic activity subsided, erosion—aggravated by block faulting—and subsequent deposit of the eroded materials created the Gila Conglomerate rock, in which the cliff dwellings are located. Continued faulting created the valley through which the river flows today. Uplifted blocks or horsts form the rolling mesas that stretch between the West Fork and the Middle Fork and the East Fork. The entire area is bordered on three sides by high mountains: the Mogollon Range to the west, the Black Range to the east, and the Pinos Altos Range to the south.

Geography

The monument lies at 6,000 feet, in a valley that is approximately a half-mile across at its broadest reach. The western unit occupies most of Cliff Dweller Canyon, which opens onto the West Fork of the Gila River. The TJ unit lies on a mesa, overlooking the confluence of the West Fork and the Middle Fork. Meandering through the valley, the river flows over gravel bottoms, at an annual average rate of 177 cubic-feet-per-second. [3] The greatest flows occur during the spring run-off in March and April, when water flows reach 354 and 386 cfs respectively.

Rainfall averages 18 to 20 inches annually at the cliff dwellings, with most of this precipitation coming in July and August. In the surrounding mountains, rainfall is higher, especially in the Mogollon Range, where elevations reach nearly 11,000 feet and precipitation averages 40 inches. A little more than 1,600 square miles of the nearby mountains is drained by the West Fork and the Middle Fork.

Within Cliff Dweller Canyon, about 100 yards below the eponymous ruins, there is a permanent spring and a perennial stream. Along the bottom of this canyon, ponderosa pine and Douglas fir grow, as well as narrow-leaf cottonwood, willows, and box-elders. The same riparian plants also grow along the Gila River, as do alders. Juniper, pinyon, yuccas, and often oaks occupy south-facing slopes of canyons and hills; ponderosa and Douglas fir grow on north-facing slopes; gramas are the predominant grasses.

Down the river from the cliff dwellings are pockets of soil adequate for farming. The slope and the breadth of valley mitigate the chilling effects of cold air that drains the higher surrounding country, and as a result, the valley has a growing season that averages 140 days. The last frost usually occurs in mid-May and the first in early October. In Gila Cliff Dwellings, the remains of eight varieties of cultivated plants were recovered during an excavation in 1963.

In addition to agriculture, the moderate climate and the well-watered land of the valley support a diversity of wild plants suitable for gathering. From the cliff dwellings, 24 wild taxa have been identified. The valley, its waters, and the highlands together support abundant wildlife, as well, including mountain lion, mule deer, elk, beaver, numerous small mammals, ducks, herons, turkeys, doves, and a lot of other birds. Today, fishermen often cast for trout—stocked rainbows—in the beaver ponds just up the West Fork from Cliff Dweller Canyon. No discernable fish bones have been found in the ruins, but remains of 22 wild mammalian species and 23 avian species have been excavated, including samples of all the animals named above. In short, the valley is a lush, sheltered, and beautiful place, and these attributes have often been noted in the historical record.

Since 1924, the monument has been essentially surrounded by the Gila Wilderness, the first officially designated in the country and still the largest in the Southwest. A single road reaches the monument from the south, through a corridor that was eliminated from the wilderness in 1953. This paved road—State Highway 15—extends 19 miles through the wilderness, and a motorist must drive another 18 miles, largely through the Gila National Forest, to reach Silver City, which is the nearest incorporated town. Because the road winds and the grades are steep, a one-way trip takes approximately 2 hours, and a visit to the monument is usually a full day's outing. The monument contains no camping facilities, but there are several nearby campgrounds managed by the Forest Service and one that is privately owned.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

gicl/adhi/intro.htm

Last Updated: 23-Apr-2001