|

GLACIER BAY

Land Reborn: A History of Administration and Visitor Use in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve |

|

| PART TWO: HABITAT PROTECTION, 1939-1965 |

Chapter VII:

Private Interests And A Second Boundary Adjustment

The biological conception of Glacier Bay National Monument as an ecological unit ebbed during the 1950s. The Park Service's commitment to habitat protection, which had been so central to the extension of the monument in 1939, began to weaken as early as 1940, when the NPS Wild Life Division was abolished and most of its scientists transferred to the Biological Survey. Repeated recommendations in the late 1940s and early 1950s to make a thorough wildlife survey in the monument were ignored. Victor H. Cahalane, who stayed with the Park Service as chief naturalist after the Wild Life Division's demise, made a brief survey of fauna and flora in 1954 in response to pressure from private interests to delete the Gustavus area from the monument. This was the last official study by a trained biologist in Glacier Bay National Monument for more than a decade. The year after his study Cahalane resigned in protest of Mission 66 plans that contemplated $1 billion of expenditures on roads and visitors' facilities for the national park system, but not one cent for biological research. [1]

Meanwhile, Park Service officials hoped to obtain appropriations for visitor accommodations and other needed improvements in Glacier Bay, Mount McKinley, Katmai, and Sitka so that these national park areas would attract some of the increasing volume of Alaska tourism which was expected to follow the opening of the Alaskan Highway. Governor Gruening and other Alaskans had been looking to the Park Service for leadership in this direction for some time. As tourism became big business in the United States, and the Department of the Interior moved toward a closer partnership with big business after World War II, the Park Service began to identify with Alaskans' vision of a thriving tourist trade in the not too distant future, with the Alaskan national parks and monuments playing an important role in it. [2]

But despite these trends, the administration of Glacier Bay National Monument remained essentially protective in the 1950s. The Park Service posted a ranger in the monument in 1950, mainly to suppress poaching, and as the small administrative presence grew, a skeletal staff at Bartlett Cove continued to devote most of its resources to patrol. Protective efforts extended to the acquisition of private inholdings, including two Native allotments at Bartlett Cove. Even though NPS planners showed more and more deference to local property holders and commercial interests in this decade, so little funding was available that most of what they proposed remained at the planning level.

Administrative Development

For twelve years Glacier Bay National Monument was administered by the NPS director, with nominal assistance from Mount McKinley National Park's first two superintendents, Harry Karstens and Harry J. Liek. In 1937, following the division of the national park system into four administrative regions, administration of the monument was transferred to the Region Four director in San Francisco, with increased assistance from "coordinating superintendents" located at Mount McKinley (1937-1951) and Sitka (1951-1953). [3]

Frank T. Been, appointed superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park in April 1939, became the first NPS official in the field to visit the monument when he and chief naturalist Earl Trager travelled there in 1939. As stated earlier, Been's administrative responsibilities included reconnaissance of the monument and initial contacts with local residents, preparation of the first master plan and administrative budget proposals, and negotiating with military commanders during World War II. Much of this work Been conducted from Mount McKinley National Park, 400 miles by air from Glacier Bay. Been's administration of Glacier Bay National Monument ended when he joined the armed services in 1943.

The regional office in San Francisco administered the monument directly from 1943 until 1953. [4] In August 1944, the Fish and Wildlife Service (newly created from the old Biological Survey and transferred from the Department of Agriculture to the Department of the Interior) made an agreement with the Park Service to assist in the enforcement of NPS hunting and fishing regulations within the monument. The custodian of Sitka National Monument, Ben C. Miller, was appointed a deputy wildlife agent and the Fish And Wildlife Service's wildlife agent in Juneau, M.L. MacSpadden, was appointed a deputy park ranger. The two men made occasional patrols of the monument together, either by chartered seaplane or by FWS patrol boat. [5]

After World War II, regional office personnel assumed some of the planning and administrative tasks that Been had managed earlier. Landscape architect A.C. Kuehl spent several weeks in Juneau in the summer of 1945 collecting information for a budget and development plan for the monument. In 1946, an NPS crew surveyed proposed development sites. Kuehl and Lowell Sumner, the biologist, inspected the monument with Ben Miller in 1945, 1946, 1947, and 1949. In the winter of 1949-50, the regional office accomplished two important land transactions: it negotiated a $900 settlement for Albert Jackson's 136-acre Native allotment at Bartlett Cove, and it reserved from mineral entry certain areas of the monument proposed as administrative sites. [6]

From mid-1947 to mid-1949, Grant H. Pearson served as custodian of Sitka National Monument and made occasional boat patrols into Glacier Bay. Pearson, a long-time ranger at Mount McKinley National Park and acting superintendent after Been joined the Army, was credited with raising morale at Mount McKinley and obtaining the confidence of various federal and territorial entities and officials, including Governor Gruening. One NPS official said Pearson understood "Alaska, Alaskans, and Alaska ways." [7] Learning of Been's return, he requested a transfer and was assigned to Sitka National Monument. In his autobiography, My Life of High Adventure, Pearson described his adjustment to southeast Alaska: "I was no townsman....Not until I stood in the prow of the launch threading its way into iceberg-studded Glacier Bay, and saw the Monument's mountains rearing up ten to fifteen thousand feet, did I begin to feel at home in this new domain." But one senses from his autobiography that this was a mere interlude until the superintendency of Mount McKinley became available. "My main patrol job, besides keeping an eye out for poachers, was to give out fishing advice, navigation maps, and warn of danger from drifting flotillas of icebergs. Cruising around on my aquatic inspection trips, I studied those bergs by the hour." One notable legacy of Pearson's tenure in southeast Alaska was the Park Service's procurement of a 50-foot cruiser-type boat in 1947, which the U.S. Coast Guard declared as war surplus. Christened the M/V Nunatak, the boat was stationed in Sitka and allowed NPS officials to patrol the monument with greater flexibility. In January 1949, Pearson received the much anticipated letter from Washington, D.C. "Back home to Mt. McKinley!" [8]

Ben Miller moved into Pearson's position upon Pearson's departure in 1949. The following spring, the regional office made plans to establish the first on-site administration of the monument at Bartlett Cove. Kuehl described how this could be done on a budget allocation of $9,800:

The limitation of funds does not permit a permanent staff, therefore I suggest that we assign personnel on a seasonal basis from July 15 to November 15, and from May 1, 1951 for the remainder of the fiscal year. In view of the fact that this is our first attempt to staff the area, I am inclined to believe that we should assign a top flight man as ranger in charge. For this position, I strongly recommend Duane D. Jacobs, Assistant Chief Ranger, Yosemite....In connection with his assignment, he should carry on public relations such as boarding all Canadian steamers entering the area; he must patrol the area, and should assist with the establishment of shore base quarters. [9]

Ranger Jacobs' first administrative task was to move a 16-by- 20-foot frame building, left by the Army on Pleasant Island, by tractor and barge to Bartlett Cove. He secured the help of two Gustavus residents, Albert and Glenn Parker. The operation took five days, most of it in a driving rain storm. Jacobs situated the building on Lagoon Island instead of the mainland, even though a survey crew had already brushed and flagged the route of the future road between Gustavus and Bartlett Cove. Perhaps he preferred the island for the psychological comfort that it afforded in such a huge expanse of bear country. He completed this original Park Service building by adding a porch, raising the roof pitch, and installing some extra bracing to withstand winter snows, all with lumber salvaged from the old cannery at Bartlett Cove. Finally, "a flag pole was cut, painted, and erected in front of the cabin." [10]

Apparently Jacobs did not attempt to board the Canadian steamers that regularly visited Glacier Bay that summer. Nor could the ships debark any passengers. As early as 1942, NPS officials had remarked on the need to revise U.S. Customs regulations that forbade Canadian steamers that plied the Inside Passage from landing passengers in Alaskan ports. These regulations were aimed at protecting American steamship companies, but since the latter had shown little interest in running passenger ships the regulations seemed capricious to Alaskans. This issue was highlighted again in a master plan of 1952, and yet again in 1957, evidently without result. Nevertheless, Canadian sightseeing ships cruised up Glacier Bay as far as [11] Muir Inlet, weather permitting, beginning in the summer of 1950.

Jacobs and the FWS warden assigned to the area, Lynn Crosby, spent about half the season on patrol, with the aim of "securing information and trying to obtain an overall picture of the poaching problem." At the end of the season, Jacobs strongly recommended that the Park Service revoke the Hoonah Tlingits' privileges in the monument. He also indicated "a possible trouble spot" in Excursion Inlet, where a couple named Allman were rehabilitiating the old Army depot into a hunting lodge. (It is not clear what property right the Allmans had obtained, but their Tongass Lodge was still attracting visitors in 1957.) To patrol the monument adequately, Jacobs believed, the Park Service needed "a small force of rangers, well equipped and extremely mobile, who may be in Excursion Inlet one day and Lituya Bay the next." [12]

But that level of law enforcement activity lay far in the future. The distances between Bartlett Cove, Sitka, and Juneau were formidable enough for boat travel, even without the added mileage to Excursion Inlet, Dundas Bay, and other areas in the monument. On rough seas, it could take four days to get from Sitka to Glacier Bay. In five months beginning May 1, 1951, Ben Miller and his new chief ranger, Oscar T. Dick (who took the monument's first permanent position), spent nearly half their time traveling between Sitka, Juneau, and Bartlett Cove or making boat repairs at one of the two towns. It was not a very satisfactory arrangement. Miller could always find paperwork to do when the boat was hauled out for maintenance, but Dick was itching to spend more time in his assigned area. [13]

Miller completed a new master plan for Glacier Bay National Monument in 1952. The plan called for nine full-time and three seasonal positions in the administration's protective division alone. These rangers would be required to operate patrol boats and at least one would be a trained airplane pilot. A ranger pilot would be a novel (and expensive) position in the Park Service, but the plan argued that the size of the monument made one or two pilots and float planes more effective than a large staff of rangers on the ground. Forest Service officials were reaching the same conclusion in this era, replacing stationary fire lookouts with air patrols. While rangers in Glacier Bay National Monument would be more concerned about poaching and visitor safety than forest fires, which were rare in the damp climate of southeast Alaska, monument visitors' boats would be relatively easy to spot from the air. It would be forty years, however, before the first ranger pilot was assigned to the area.

The 1952 Master Plan definitely located monument headquarters at Bartlett Cove, "because of its close proximity to the Gustavus Airfield." Construction of a 4.2-mile road from Bartlett Cove to the terminus of the CAA service road was slated to begin that year. The Bartlett Cove area would include administrative buildings, employee housing, a large dock for ocean-going vessels, gasoline and oil storage tanks, floats for boats and planes, and a hotel. The plan also described a "primary seasonal base" in Sandy Cove, consisting of a small lodge, ranger housing, and other appurtenances. [14]

In the 1952 Master Plan can be seen the basic outlines of the park's present-day infrastructure. It largely superseded earlier plans prepared by Been (1942) and Kuehl (1945), and formed the basis for updated and revised editions of the master plan in 1957, 1960 and 1964. This series of master plans would guide the development of the physical plant at Bartlett Cove during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The Gustavus Community

In 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower excluded from Glacier Bay National Monument most of the Gustavus forelands area, ostensibly to "rid it of nonconforming uses and make additional land available for agriculture." [15] But this action was not simply a corrective for the government's inclusion of the small settlement within the monument in 1939. Rather, it was illustrative of a broad change in environmental policy in this period, as the Truman and Eisenhower administrations sought to roll back conservationists' restrictions on the free market and the rights of property. [16]

A hallmark of the New Deal approach to conservation was its holistic view of natural resources and society. Harold Ickes, Henry Wallace, and other prominent New Dealers favored comprehensive planning that would integrate the needs of society with a wise stewardship of the environment. The Tennessee Valley Authority, the National Resources Planning Board, the Soil Conservation Service, and the Resettlement Administration were just a few of the many New Deal programs that blended social engineering and conservation. The New Dealers' analysis of nature and society began with the public welfare, not with the rights of property; long-term social goals had to take precedence over short-term private interests. [17]

Thus, when NPS officials considered how to deal with the handful of homesteaders near Point Gustavus in 1938-39, they began with the premise that the area would not sustain an agriculture-based community indefinitely, and that the public demand for a brown bear sanctuary outweighed the stubborn hopes of a few dozen settlers. They predicted that the community would wither and vanish in a matter of years. Ironically, it was the promise of the Park Service's own development plans for the monument, together with the windfall of the Gustavus airport, that kept the Gustavus residents from quitting their hardscrabble existence, realizing that tourism would eventually raise their property values and create opportunities to make an easier living. This situation naturally bred resentment on both sides, laying the foundation for a lingering community relations problem between the Park Service and Gustavus. [18]

Gustavus residents liked to point out that their settlement antedated the national monument by several years. The first settler was Ernest O. Swanson, who arrived some time before World War I, cleared some land, raised a few vegetables, and left several years later. [19] He was followed by the Abraham Lincoln Parker family, who came in 1917 and stayed. Soon a number of other families had filed homestead claims on the small plain beyond Point Gustavus, and several of these residents wrote letters of protest to George Parks when he made his survey of the proposed monument in 1924. By then the community had a small network of roads and bridges and was given the name Gustavus by the U.S. Postal Service. The Alaska Road Commission built a large dock on the tideflats in 1929, and a federal relief project added a long berm-and-trestle approach to it four years later. A Forest Service report gave the population as 29 in 1935. [20]

Gustavus was not the only place in what would become Glacier Bay National Monument to attract settlers in the 1920s and 30s. Joe and Muz Ibach built a cabin on Icy Point around 1920 and trapped fox, marten, and other furbearers along the outer coast, before building a homestead on Lemesurier Island. [21] Doc Silvers and his wife began prospecting in the Dundas Bay area around 1929, grubstaked by a Juneau woman named Anita Gornick. By 1939, Silvers had built three different homes in Dundas Bay on three separate tracts. He and his wife shared the bay with three other white residents: Stanley Harbeson, who came in 1933 to work on Silvers's claims and soon turned to trapping, and Horace Ibach and his wife, who lived at the old cannery site. [22] There were fox farmers on Strawberry Island, the Beardslee Islands, and Willoughby Island, the latter occupied since the mid-1920s. And far away on Cenotaph Island in Lituya Bay, Jim Huscroft established himself in 1917 and stayed for twenty-two years.

When Mount McKinley National Park superintendent Frank T. Been and chief naturalist Earl Trager inspected the national monument in 1939, they focused a large part of their interest on these inhabitants. Clearly, their persistence in the area would detract from the purpose of the monument as a nature preserve, and was therefore undesirable. Whether or not they stayed, however, depended on how they made their livelihoods. Trappers like Huscroft and Harbeson had little choice but to leave, since trapping in the monument was illegal. Similarly, the fox farmers would shortly have to depart. But the homesteaders' intentions were more problematic, and most of them owned some acreage around their homes.

Trager was struck by the futility of the homesteaders' efforts at farming. In his report, the chief naturalist described how the homesteaders had hung on to their land through a series of failed enterprises: growing vegetables for the Juneau market, milling lumber and raising beef cattle for the canneries, trapping, raising corn, rye, and hay, prospecting for gold up the bay. Albert Parker, the son of A.L. Parker, who had the best looking farm of anyone in Gustavus, told Trager that they had once had 162 cattle grazing on the forelands but currently had about 50 head. It took two years for a grazed pasture to recover. Parker claimed that wolves and coyotes had killed a lot of their calves until they had built an eight-foot-high trapwire fence around the edge of the forest. Trager and Been walked several miles from homestead to homestead, around the margins of weedy fields, and along the road berm that ran out to the dock, and found nearly the entire area submerged in ankle-deep water. It was Trager's hope and expectation that these residents would soon pull out in discouragement. [23]

Been seemed to regard the Gustavus residents somewhat more sympathetically than Trager did. Visiting the settlement again in 1940, he learned that the Chase family supplemented their small farm income by trolling for salmon and operating a garage in Juneau, and that the Parkers had recently sent five tons of gold ore from their claims up the bay to a smelter in Washington. Sam Buoy stopped Been at the dock and told him he hoped to retain his farm because he had been there eight years and had put away some money working at a cannery each summer. Buoy allowed that some of his neighbors wanted to sell and were hoping the government would buy them out. [24]

The Park Service nudged certain residents to leave the monument voluntarily, and pulled wires to get others evicted. Doc Silvers received a letter from Assistant Secretary of the Interior Oscar Chapman politely informing him of the NPS ban against trapping. John Johnson, who ran a fox farm on Willoughby Island, received a one-year special use permit to give him time to liquidate his assets. The Pacific American Fisheries Company was asked to evict Horace Ibach and his wife from its Dundas Bay cannery and to donate the site to the Park Service. [25] But there was no money for acquiring the patented lands around Point Gustavus and no one in the Park Service suggested it.

A few oldtimers would bitterly relate years later how Been told them that they would be unable to make final proof on their homesteads and must cease operations, and that those who owned their land would be forced out of business. The men who listened to these allegations, finding nothing to substantiate them in the written record, doubted their veracity. [26] But others had noted Been's "lack of finesse" in dealing with people, and he certainly created misunderstanding about the Hoonah Tlingits' privileges in the monument. [27] It seems plausible, therefore, that Been did convey to these people the idea that the Park Service intended to have their land.

Whether some Gustavus residents mistrusted Been or simply wanted a scapegoat for their economic woes, they lashed out at the Park Service in 1941. They claimed that the extension of the monument was their ruination: the surveyed lands surrounding the community were now closed to homestead entry and grazing, their school had closed, and the dock was falling apart (the Alaska Road Commission having decided that it was now the Park Service's responsibility to maintain it). The Chicago Tribune described the community's tribulations under the headline, "Alaska Pioneers Blast Ickes for Park Land Grab." Governor Gruening and Alaska delegate Tony Dimond proposed that the Gustavus area should be excluded from the monument. [28]

The Park Service responded that the Gustavus forelands were integral to the area's natural boundaries, and that these settlers' economic difficulties resulted not from Park Service pressure, but because the land was overgrazed and too wet to raise hay, and the local market for beef was shrinking as canneries closed down. [29] The Department of the Interior's tough stand, based as it was on the view that the farms in this locality should properly revert to a wilderness condition, was emblematic of New Deal conservation policy. Before this dialogue proceeded any further, however, it was interrupted by the temporary transfer of the area to the War Department, which left the Gustavus residents free to graze their cattle wherever they pleased.

After the war, Gustavus residents renewed their fight with the Park Service. In 1946, 33 residents petitioned Alaska delegate E.L. Bartlett and the Department of the Interior to open the area to settlement again. Bartlett forwarded the petition with his endorsement to Secretary of the Interior Julius A. Krug. Asked to investigate it, the Park Service found that the likely result would be a commercial subdivision. The Gustavus airport had considerably altered the picture, causing land speculation and a nearly complete turnover of the town's population since 1939. [30] If the community were allowed to grow, there would be more demand for grazing, more pressure on the brown bears, more "submarginal development." To get by, Gustavus residents would increasingly rely on "commercial exploitation based on the development of Glacier Bay National Monument and Gustavus Airport." [31]

It was at this time that some conservationists began to insist that the airport should be deleted from the monument, as noted earlier. While this demand emanated from a different source and perspective than that of the Gustavus residents, the Park Service's response to it was based on the same principle--that the biological wholeness of the monument must be maintained. Cahalane stated the agency's position most forcefully:

I feel strongly that the entire southeastern portion of the Monument, between Glacier Bay and Excursion Inlet, north of Icy Strait, is a unit which is vital to the long-time administration and protection of the Monument. This is especially true of its important faunal features. If we permit the "farming" community at Gustavus to expand, with cattle grazing sure to be a feature, we will find it impossible to keep any carnivorous mammals in the Monument east of Glacier Bay. I consider it much more important to keep control of the entire Gustavus area, and thus save the animal life, than to excise the airport from the Monument. [32]

This was a clear expression of New Deal conservation--using federal control in the public interest to prevent rampant, environmentally unsound, economic growth. However, by 1948 New Deal conservation was on the wane. Development interests were increasingly gaining a more receptive hearing. The deepening Cold War and big defense spending generally strengthened the hand of those who sought freer access to natural resources, and nowhere was this truer than in Alaska. Governor Gruening was a master at linking Alaska's strategic location near the Soviet Union with its need for rapid development of an economic base. "Alaska's growth and development are...of great national concern," he wrote in 1953. He welcomed the construction of southeast Alaska's first pulp mill at Ketchikan in 1953--twenty-five years after the industry was first proposed. He called for a "thorough overhauling" of Alaska's land laws in such manner as "to promote settlement....Nowhere else under the flag do national forests blanket a whole economic area or include and circumscribe a state's principal urban centers." [33]

The Gustavus area came up for debate again in 1954, when Charles Parker, the oldest son of A.L. Parker and now himself approaching old age, began another letter-writing campaign. Parker demonstrated that his Cold War rhetoric could match anyone's:

It is time every red-blooded Alaskan and American write his Delegate and Congressman and insist that pressure be put on and the release of Gustavus Land from the Glacier Bay National Monument be secured at once. Then we can settle this section with veteran fighting men, and come what may, we will be able to produce thousands of tons of food for our people and military force. [34]

One of Parker's letters, addressed to a U.S. senator, eventually found its way into the hands of the NPS director, Conrad L. Wirth, with a request from Assistant Secretary Orne Lewis for a report.

Wirth briefly reviewed for Lewis the history of the boundary: the desire to protect brown bear habitat, the consideration given to Admiralty Island, the extension of Glacier Bay National Monument instead, the expectation that the area would be developed and made a national park, the conclusion that the land around Gustavus was too marginal to sustain an agricultural settlement. "It seemed to us, therefore, that the wisest course in the long run would be to acquire the privately-owned lands in the vicinity of Gustavus and include them in the Monument. Unfortunately, we have not been able to make much headway on the land acquisition." Wirth suggested that this fact, and the airport development, now made a boundary adjustment advisable. He urged that the department contract with a university to make a soil study and recommend new boundaries accordingly. [35]

In July 1954, two men from the Alaska Agricultural Experiment Station and one from the Soil Conservation Service made a study of the Gustavus area. Their soil survey showed that the ground was poor and rocky. The tilled acreage at the time of their survey amounted to one 5-acre field of mixed grain and three small gardens. Hay lands were untended, weedy, and showed poor growth. Most residents lived on government salaries or pensions, not farm produce. "The land-use history of the Gustavus area," they concluded, "probably would have been little different under the Park Service, the Forest Service, or under unrestricted public domain. The economic conditions of the past twenty to thirty years in Southeastern Alaska are not to be ignored." Provided that new markets developed with the newly opened cut-off road connecting the Alaskan Highway with Haines, perhaps six new homesteads could successfully raise crops in addition to the fourteen already patented if the land were returned to the public domain. But the survey team warned that non-farmers would likely acquire the land for speculation; in recent years, only one in four Alaska homesteaders had shown any intention of farming. [36]

The report essentially confirmed what Coffman, Trager, and Been had found in 1938 and 1939. Nevertheless, the authors recommended that the area be returned to the public domain. Their reason: it had "no particular association with the original reasons presented for establishment and maintenance of Glacier Bay National Monument." The area was "not necessary to the purposes of the Monument." They offered this conclusion despite the fact that everything these men knew about brown bear use of the area they had learned from the local residents. [37]

Wirth sent his top biologist, Victor H. Cahalane, to investigate the problem from another perspective. Cahalane had a scant ten days to survey the monument's wildlife habitat and assess the relationship of the Gustavus area to the whole. He observed that forty years of human habitation around Point Gustavus had altered the local ecology, probably benefiting some animal species while driving out others. This could be "corrected, in part, if the private lands were acquired by the Government." Cahalane stressed that most of the monument's vast acreage was virtually devoid of animals, and that the monument's function as a brown bear sanctuary was mainly confined to the coastal strip and the lowland areas south of Adams and Charpentier Inlets. From this standpoint, "proposals to eliminate vegetated areas...from the sanctuary should arouse serious concern." [38]

Wirth was under strong pressure from the Department of the Interior to accede to the boundary change. He did not wait for Cahalane's report before writing a memorandum, dated September 21, 1954, which stated that the Park Service would raise no more objections to it. As for the possibility that speculators would claim homesteads, Wirth wrote to the interior secretary, "we understand that the Department wishes to open the lands to settlement as soon as they are released from Monument status." [39]

On March 31, 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed a proclamation returning the Gustavus area, amounting to approximately 14,741 acres of land and 4,193 acres of water, to the public domain. [40]

The Gustavus exclusion only partially alleviated bad feelings between local residents and the Park Service. Shortly after the proclamation, Superintendent Schmidt was asked if NPS personnel residences would be better located in Gustavus than Bartlett Cove. Schmidt replied in the negative, offering several practical reasons in favor of Bartlett Cove and then adding a few comments about Gustavus:

There is not at present any facilities at Gustavus that would make for better living or better morale than can be provided by the proposed installation at Bartlett Cove. There is a problem of daily living in close proximity with "homesteaders" who are not too happy about any government regulation, and who do not hesitate to carry on a "cold war" with any people connected with the government. This situation will not improve with advent of additional homesteading.

Changes in personnel at the C.A.A. establishment have been frequent. The C.A.A. have found it next to impossible to keep families with children at Gustavus for any length of time, and have not had families with school age children stay on the job for more than one year. Although efforts have been made to encourage employees with school age children to remain at Gustavus, they have not been successfull [sic] enough to provide for the minimum attendance required for provision of school facilities by the Territory of Alaska. [41]

Although the land exclusion reduced the amount of federal control over the local community, Gustavus residents would continue to feel unduly restricted by their proximity to the monument, particularly after several other southeast Alaska communities became linked by a state car ferry system in the 1960s. Community relations would continue to be a ticklish problem of Glacier Bay National Monument administration in the years ahead.

A Boundary Correction in Excursion Inlet

When Wirth first raised the subject of a boundary adjustment with the new governor of Alaska at the beginning of 1954, the governor "strongly recommended it," and lumped an area of prime pulpwood timber in Excursion Inlet into the discussion for good measure. The new governor was B.F. Heintzleman, former head of the Forest Service in Alaska, and he remembered how the Park Service's John Coffman had contested that timber with him back in 1938. Heintzleman claimed there had been a misunderstanding about the boundary. [42]

Wirth informed his regional director, Lawrence C. Merriam, about Heintzleman's claim, and Merriam's staff dug through the old files. It seemed that Coffman's and Dixon's report in 1938, which Heintzleman had seen, had argued emphatically that the Excursion River was one of the principal salmon spawning streams in the area, making the head of Excursion Inlet and the river's watershed important brown bear habitat. Furthermore, Coffman and Dixon had recommended that the old cannery should be included within the monument for an administrative site. A boundary map dated April 18, 1939 showed the old cannery site within the monument, as desired. But a small-scale U.S. Geological Survey map of 1951 showed the cannery outside the monument, with the boundary following a different spur from the divide down to Excursion Inlet. A close reading of the presidential proclamation of 1939 showed that there were indeed two possible interpretations of the boundary description.

Merriam recommended that the Park Service agree to the boundary shown on the USGS map, and stand willing to discuss minor adjustments to it should Heintzleman want. He suggested that Superintendent Schmidt be requested to seek information "judiciously and informally" from Forest Service officials regarding their plans for timber harvesting in the area. [43]

Cahalane recommended against the deletion in Excursion Inlet, as it was important wildlife habitat and a good example of coastal forest. "The commercial lumber value [was] too small and too fleeting to justify destruction." [44]

Wirth decided that the boundary revision in Excursion Inlet was justified because the boundary had been "incorrectly described" in the proclamation of April 18, 1939. The area covered about 10,184 acres. This area was returned to the Tongass National Forest by the President's proclamation of March 31, 1955. [45]

Development of a Physical Plant

In 1956, Director Wirth announced Mission 66--a ten-year program of planning, rehabilitation, and development for all units in the national park system. The program was dramatically timed to reach completion on the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the NPS. By effectively publicizing the needs of the national parks, Wirth obtained strong support for the program from both the Eisenhower Administration and Congress. While Glacier Bay National Monument and the three other Alaska areas remained relatively remote for vacationers in this period, they nevertheless received an infusion of money for development.

The driving force behind Mission 66 was the need to accommodate a burgeoning public use of national parks nationwide. Visits to parks had risen from 17 million in 1940 to 33 million in 1950, and would pass 72 million in 1960. [46] Mission 66 planning for each park or monument, therefore, was keyed to careful projections of visitor use in the future. Most Alaska planners believed that visitation to Alaska areas, while starting at a low level in the mid-1950s, would increase at an even faster rate than park visitation in the rest of the nation. The Mission 66 prospectus for Glacier Bay National Monument predicted that visitation would reach 10,000 to 15,000 by 1966, a three- to five-fold increase in ten years. "The Mission 66 program proposes developments and management practices designed to provide optimum use and enjoyment of the area in ways consistent with the preservation of its resources, and the convenience and safety of visitors," the prospectus stated. Like earlier planning documents for the monument, the Mission 66 prospectus envisioned a virtually roadless area where travel would be primarily by boat. The monument was "essentially an undeveloped area," requiring "a minimum of developments." [47]

But even a small physical plant required a much greater outlay of money than the monument had heretofore received, and Mission 66 provided Glacier Bay National Monument for the first time with significant funds for development. Indeed, during the first four years of the program Glacier Bay received $1,823,000 in Mission 66 funds, topping the amount expended for Mount McKinley and exceeding the combined amount expended for Katmai and Sitka. [48]

Prior to the commencement of this construction program the patrol cabin on Lagoon Island in Bartlett Cove was the only fixture of NPS administration in the area. Park ranger Bruce W. Black occupied this cabin with his wife and three children for short periods during the mid-1950s, but otherwise it saw little use. [49] In 1955 the Park Service replaced M/V Nunatak with a larger, 65-foot motor vessel, Nunatak II, which was based in Bartlett Cove and served as a combination patrol boat and ranger station. [50]

Beginning in 1957, construction began on a pier, dock, and seaplane float, a water and sewer system, and two residences. [51] This was followed shortly by a larger dock, repair shop, power plant, small administration building, and more employee residences. A permanent ranger station opened for business in 1960. [52] By 1965, the monument was equipped with two outboard patrol boats in addition to Nunatak II, a 5-ton snowplow, a half-ton pickup, a station wagon, a bulldozer, and a backhoe. [53]

While construction of facilities at Bartlett Cove proceeded, the Park Service established a strictly administrative site fifteen miles north of Juneau at a place called Indian Point. The development of the Indian Point site resulted from the decisions of two succeeding superintendents, Henry G. Schmidt and Leone J. Mitchell. Schmidt, appointed superintendent of both Glacier Bay and Sitka national monuments in 1953, decided to move the superintendent's headquarters from Sitka to Juneau in 1957. Although this move was resisted by the mayor of Sitka, Schmidt justified it on the grounds that the new location was closer to Glacier Bay, and would allow better access to the governor of the territory and other federal agencies. [54] It was a timely move, for Mission 66 developments in the next few years would go far toward making Glacier Bay National Monument much the more important of the two monuments from an administrative standpoint. Schmidt established an NPS office in the federal building in downtown Juneau. But he left it to superintendent Mitchell, who took his place in 1958, to develop a permanent administrative site at Indian Point.

This site consists of sixteen acres of upland where Indian Point juts into Auke Bay. Auke Bay opens into Stephens Passage and lies directly on the water route between Juneau and Bartlett Cove. A road along the edge of the mainland connects Auke Bay to Juneau, fifteen miles to the south. Mitchell selected this site primarily in order to cut down travel time for Nunatak II during resupply operations. It was also cheaper to build a superintendent's residence and other employee housing at Indian Point than to purchase or rent space in Juneau. Moreover, Auke Bay was itself the site of a Forest Service ranger station and a Fish and Wildlife Service research installation. [55] The concentration of these federal agency facilities at Auke Bay has proven useful.

For many years Indian Point served as the superintendent's headquarters while the staff at Bartlett Cove was under the direct supervision of a resident chief ranger. Sitka National Monument received its own superintendent in 1969 and was redesignated a national historic park three years later. The superintendent of Glacier Bay National Monument, meanwhile, made Bartlett Cove his summer headquarters and moved back to Indian Point during the off-season.

Although the superintendent's residence was eventually relocated permanently to Bartlett Cove in 1978, Indian Point acquired another function, as home port for the NPS vessel. In 1962, Mitchell decided that it would be more efficient to base M/V Nunatak II at Indian Point rather than Bartlett Cove, as this vessel came to be used less for patrol and more for resupply and logistical support of science in the monument. Consequently the Park Service obtained a lease on 4.7 acres of tideland in Auke Bay on which it constructed a dock. [56] In 1968, M/V Nunatak II was replaced by M/V Nunatak III. [57] Indian Point continues to serve the monument as a permanent moorage for M/V Nunatak III; in 1990 the dock facility was equipped with a crane, new dock flotation, and improved electrical wiring. [58]

Mission 66 established the basic facilities for administering the monument. With the completion of the long-awaited visitor lodge in 1966, campground, Bartlett Cove nature trail, and concomitant increases in visitor use and staffing, the monument entered a new phase of administration. These important developments in Glacier Bay National Monument coincided with broad changes in the national park system and the wilderness preservation movement.

|

| View of the Nunatak as seen from the cabin on the island west of NPS headquarters. This boat served the NPS from 1947 to 1955, when it was replaced by the Nunatak II. (GLBA Collection.) |

|

| The Nunatak II, which served the agency from 1955 to 1968, is shown with a smaller boat at Indian Point, in Auke Bay (near Juneau), November 1966. (Robert Howe Collection, photo GB 519.) |

|

| Glacier Bay Superintendent Leone Mitchell (left) and Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, on the Nunatak II in Glacier Bay National Monument, July 31, 1965. (Ted Swem Collection.) |

|

| The Nunatak III, which has served the park since 1968, is seen in this March 1974 photo. (GLBA Collection, photo X-175.) |

|

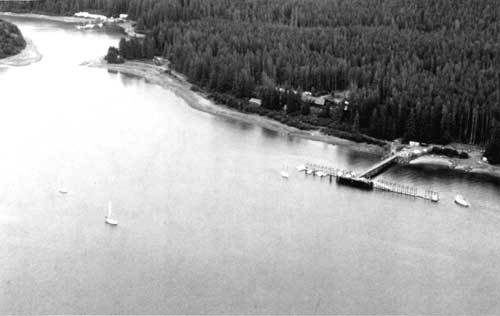

| Aerial photo of NPS headquarters complex, looking south, during the mid-1970s. Shown (left to right) are lumber shed, maintenance shop (with attached marine railway), headquarters, and boat dock. The string of trailers served as seasonal quarters for NPS rangers and interpreters. (GLBA Collection) |

|

| Aerial photo taken over Bartlett Cove shows NPS headquarters area (top left), Glacier Bay Lodge (center, behind trees) and Outer Dock (right). Laurel Devaney, then a seasonal interpreter, took this September 1984 photo. (GLBA Collection, photo X-1-1.) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 24-Sep-2000