|

GRAND TETON

A Tale of Dough Gods, Bear Grease, Cantaloupe, and Sucker Oil: Marymere/Pinetree/Mae-Lou/AMK Ranch |

|

BEROL ERA

As executor of Johnson's estate, the Irving Trust Company retained Slim Lawrence as caretaker of the Mae-Lou property for the period of 1931-36. One unfortunate event during this time was their ordering Slim Lawrence to destroy the Sargent cabin. It was the feeling of Irving Trust that the cabin detracted from the appearance of the site they had selected for the Johnson grave (Fig. 43) (Teton Magazine, 1977). Lawrence tried to prevent the destruction; but under threat of being fired, he carried out the elimination order (W. Lawrence, 1978).

|

| Fig. 43. Deserted Sargent cabin, 1929. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

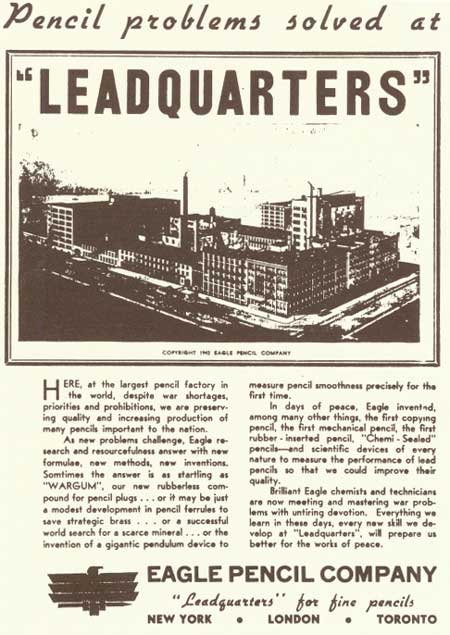

During this period, Alfred Berolzheimer and his wife Madeleine, two Easterners, became acquainted with the Rocky Mountain West through stays at the Miller dude ranch between West Yellowstone and Bozeman, Montana (Untermyer, 1978), and the Belden ranch just west of Meteetsee, Wyoming (W. Lawrence, 1981). Alfred and his brothers, Edwin and Henry, were fourth generation family members engaged in the manufacture of pencils and writing materials through the family's Eagle Pencil Company of New York City. In 1856, this business had been started by their great-grandfather, Daniel, a resident of Fuerth, Bavaria, in a small factory in Yonkers, New York. The business grew so rapidly that in 1877 a city block on Manhattan Island was acquired for the expanding industry (Fig. 44) (Harvard Univ., 1962; N.Y Times, 1922; 1949).

|

| Fig. 44. Eagle Pencil Co. ad., New York City, 1942. (Berol Corporation Coll., Danbury, CT.) |

Alfred was born on October 5, 1892, in New York City to Emil and Gella Goldsmith Berolzheimer. Emil immigrated to this country in 1883 to work in the established Eagle Pencil Company and became its President in 1885 (N.Y. Times, 1922). Alfred's boyhood was spent in New York City and Tarrytown, New York. He attended preparatory school at the prestigious private boy's school, Phillips Exeter Academy (Who's Who, 1974-75; K. Berol, 1986). The Academy was founded in 1781 in New Hampshire's second oldest town, Exeter, which is described as "perhaps more than any New England town, reminiscent of an English provincial village" (Anon., 1985). In 1913, Alfred graduated cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts degree from Harvard University. Following graduation from college, Alfred was employed by the banking firm of Speyer and Company where he gained experience in commercial, industrial and international finance (Harvard Univ., 1962; Jackson Hole News, 1974).

During 1915, Alfred started his work with the family-owned Eagle Pencil company, which became the Berol Corporation in 1969 (N.Y Times, 1974). However, World War I interrupted this employment: Alfred was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in 1917 and served with the Army in France. At the end of World War I, Alfred once more returned to the Eagle Pencil Company (Harvard Univ., 1962).

Elise Untermyer remembered Alfred as being tall and well-built with reddish-blonde hair. Throughout his youth, Alfred had been waited on "hand and foot" with numerous servants to care for his needs. As a young man, the girls liked to date him because they always received a special, exotic green orchid (grown in the family greenhouse) which was quite distinct from the usual purple variety. One of the girls who dated Alfred was Madeleine Rossin, the youngest of two daughters of the Morris Rossins (Untermyer, 1978; 1986).

Madeleine was born in New York City and was brought up there and in Europe, living a sheltered life (K. Berol, 1986a). Elise Untermyer, a friend, recalled that she was not only protected from germs but from contact with persons unknown to her parents. Madeleine went to a private school after some years of lessons at home. She was carefully chaperoned by her mother or a governess at all times (Untermyer, 1986).

A long-time friendship culminated with Alfred and Madeleine being married on May 4, 1922 (N.Y Times, 1922a). Their only child, Kenneth Rossin, was born on April 16, 1925, in New York City (Who's Who, 1984-85). While they maintained an apartment in that city, Faraway Farm at Cross River, New York, was the Berols' primary residence (Fig. 45) (K. Berol, 1986). Sometime during World War II, Alfred and his brother, Henry, changed their name from Berolzheimer to Berol (Berolzheimer, No date).

|

| Fig. 45. Berol Faraway Farm, Cross River, NY. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

By 1946, Alfred had experience in nearly every part of the Eagle Pencil Company, as well as having served as Secretary, Treasurer and Vice President. In that year, Alfred was elected President of the Company and in 1962, he was elected as Chairman of the Board of Directors. In honor of his 70th birthday and nearly 50 years with the Company, the Board of Directors passed the following resolution (Harvard Univ., 1962):

Mr. Alfred C. Berol had devoted nearly half a century to the welfare and development of the Eagle Pencil Company; and,

WHEREAS during this period his far sighted vision, penetrating intellect, and creative imagination were dominant factors in the Company's growth and success in the United States and abroad; and,

WHEREAS his outstanding leadership, personal integrity and warm understanding of human values have been a source of inspiration to his associates; and,

WHEREAS on the occasion of his 70th birthday, the Members of the Board of Directors wish to acknowledge their deep appreciation of Mr. Alfred C. Berol's dedication to the affairs of the Company and to express their great affection and esteem for him,

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT UNANIMOUSLY RESOLVED that there be established an endowment fund at the Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration. . . known as the Eagle Pencil Company-Alfred C. Berol Fellowship...."

Harvard University (1962) further commented on the Eagle Pencil Company:

"This large and complex company, a leader in its field throughout the world, is a remarkable example of a relatively rare institution—a major concern entirely owned and continuously operated by the same family."

By 1962, the Eagle Pencil Company headquarters and main plant had moved to Danbury, Connecticut (Fig. 46). Other factories were located in England, Canada, Mexico, Columbia and Venezuela. In addition, they operated a sawmill and the Hudson Lumber Company in California where they pioneered the use of California incense cedar in their products (Harvard Univ., 1962; Who's Who, 1974-75).

|

| Fig. 46. Berol Corporation, Danbury, CT. (Berol Corporation Coll., Danbury, CT.) |

The Berolzheimer brothers' family background apparently generated their mutual interest in the outdoor activities of hunting and raising purebred animals. Edwin had one of the finest kennels in the U.S. of field trial Irish setters (N.Y Times, 1949). Henry raised English pointers and Tennessee walking horses on his 10,000-acre Georgia plantation. He also served as President of the Georgia Field Trial Association (N.Y Times, 1976). As early as 1932, Alfred and his family spent their summers in various locations in the Rocky Mountains. Alfred acquired much of his early love of the wilderness and hunting in the Canadian Rockies around Jasper Park, Alberta, and at dude ranches in Montana and Wyoming (K. Berol, l986; W. Lawrence, 1981).

During one of Alfred's visits to the Montana Miller ranch, he learned that the Sargent-Johnson property was for sale (K. Berol, 1986a). Following up on this lead, he was soon negotiating for the property with the Irving Trust Company. On June 15, 1936, Irving Trust secured quiet title to the property and on June 29, 1936, Alfred purchased the 142-acre Sargent-Johnson property including the Mae-Lou-Lodge and nine outbuildings for $24,300 (Teton Co., 1936; 1936a; Berolzheimer, 1936; 1940).

Immediately following his purchase of the Johnson-Sargent property, Alfred initiated a variety of activities: (1) Slim Lawrence and his wife, Verba, continued as caretakers of the property; (2) the water system of the Mae-Lou-Lodge was remodeled; (3) New York architect, George W. Kosmak, was retained to draw plans for a new log residence for the Berol family; and, (4) Paul T. Colbron of Wilson was appointed as Mr. Kosmak's Wyoming representative (Berolzheimer, 1936; 1936a).

Less than a month after the purchase, the Berols arrived at their ranch. Madeleine and Kenneth returned to New York in early fall and Alfred stayed until October 18 to elk hunt and attend to construction details. During 1936 and the next summer, they stayed in the Mae-Lou-Lodge (V. Lawrence, 1936-40).

One important project completed in 1936 was the acquisition of a horse grazing permit and construction of a fenced pasture on the Teton National Forest. This pasture was located south of Arizona Lake and was large enough to accommodate 10-15 of the Berols' horses (W. Lawrence, 1978; V. Lawrence, 1936-40).

Construction of the new Berol Lodge was started in the Spring 1937 with the Nelson Brothers of Jackson hired as the general contractor. Ernest Moore, who did the fireplace work for Johnson, was hired as a subcontractor for the 6 fireplaces and 3 stove chimneys scheduled in the new house. The deadline for completion of the building was the Fall 1937 (Berolzheimer, 1936a). Coincident with these activities, a new name, the AMK Ranch, was adopted. Represented were the first letters of the first name of each member of the family (Jackson Hole News, 1976).

In contrast to the Mae-Lou-Lodge log source at Moran Bay, logs for the Berol residence were cut on the northwest end of the Arizona Lake meadows. The large spruce logs on each side of the main entrance were cut in the swamp 1 mile north of Moran. Rocks for the fireplaces, except in the master bedroom, came from the Gros Ventre Canyon. The master bedroom fireplace rocks are pink volcanic tuff quarried near Rexburg, Idaho. Some of the flat stone slabs used for walkways were taken from Beaver Dick's abandoned homesite several miles north of the AMK (W. Lawrence, 1978).

On-site work commenced on May 17, 1937. The nature of the log construction project required a sizeable work force, which in those depression times provided a considerable benefit to the local economy. In addition, the quality of work performed was very high; because for every position filled, there were several unemployed skilled workers waiting to take over (W. Lawrence, 1978; V. Lawrence, 1936-40).

Probably, the many anecdotes about Alfred had their beginning at this time with his fascination with the dynamiting of the tree stumps from the building site. Bill Rodenbush of Moran was the "powder monkey" hired for the job. Alfred closely followed Rodenbush; and when Rodenbush was ready to set the dynamite off, he would poke Alfred in the ribs and Alfred would shout, "Powder, powder gentlemen" in a most memorable New York accent (W. Lawrence, 1978).

In contrast with Johnson's Mae-Lou-Lodge, the new Berol residence was an elongated, single-story structure covering some 5,200 square feet (Fig. 47). It contained many windows overlooking Jackson Lake. Consequently, those windows produced a light and airy atmosphere which resulted in a more esthetically pleasing environment than that of the Mae-Lou-Lodge. Kenneth Berol (1986a) related, "An interesting feature was the angular bay in the dining room. Alfred got the idea from a lodge in the province of Quebec, Canada where he went salmon fishing. Told that such angular construction was impossible with logs, he persisted and prevailed." The building was not ready for occupancy until late July and early August 1938 (V. Lawrence, 1936-40).

|

| Fig. 47. Berol Lodge, west side, 1977. (Kenneth Diem Coll., Laramie, WY.) |

The general motif of the furnishings of the Berol Lodge became a mix of Western crafted wood furniture and Southwestern Indian artcraft in the form of rugs and pottery. Many of the pine furniture items were produced in Bozeman, Montana (Fig. 48). Big game trophies were hung on the walls and over fireplaces. Fig. 49 best depicts the character of those furnishings.

|

| Fig. 48. Hauling new furniture from Gardiner and Bozeman, MT, to Berols' AMK Lodge. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 49. Madeleine and Alfred Berol in AMK living room. (William Balderson Coll., Meadowbrook, PA.) |

In addition to the main lodge construction, several other projects were being completed. Remodeling of the caretaker's quarters in the Mae-Lou-Lodge provided better winter heating and more window space. The hayloft of the Johnson barn was remodeled into three sleeping rooms and a bath. To handle the anticipated horse use at the ranch, they constructed a new pole and frame barn and a log cabin to store saddles and other horse gear (Berolzheimer, 1936a; V. Lawrence, 1936-40; W. Lawrence, 1978).

Before construction activities were completed, Alfred became involved in several frustrating long-term events. On June 8, 1938, just before the main lodge was completed, a storm on Jackson Lake washed away 5 feet of the ranch shoreline and undermined the boathouse porch (V. Lawrence, 1936-40). In early 1939, Alfred began a long and futile battle with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to lower the maximum level of Jackson Lake or to get some agency to build cribbing to prevent further wave erosion of his property (Berolzheimer, 1939; 1939a).

In correspondence to the Director of the National Park Service, he lamented, "The fine work which the Park Service has done in cleaning up Jackson Lake is gradually again being undone by the unsightliness of washed away shores, and I do hope that an effort will be made to maintain this magnificent country (probably the finest we have in the entire United States) in as pleasing a condition as possible in spite of the damage caused by man (Berolzheimer, l939b).

Horace Albright's letter to Alfred explained the frustrating situation:

"The divided jurisdiction I think, is the chief difficulty in the way of getting some workable plan developed. The National Park Service has no jurisdiction whatever over Jackson Lake. The Lake itself is under the Reclamation Service and the borders of the Lake are under the Forest Service" (Albright, 1940).

After his personal campaigning failed, Alfred invested thousands of dollars (W. Lawrence, 1978) in efforts to establish riprap devices to prevent the wave erosion (Fig. 50). The futility of that approach was painfully evident when a severe storm on Jackson Lake destroyed all of those riprap structures in a brief 10 minute period in July 1941 or 1942 (W. Lawrence, 1978). Alfred was still investing in some kind of device to stop erosion as late as 1966 (Seaton, 1966).

|

| Fig. 50. Berol cribbing and riprap, Jackson Lake, early 1940s. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

In 1953, the issue was very much alive when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation budget request included $5,000 for condemnation of Alfred's shoreline area (A. Berol, 1953). What is not clear is whether Alfred or the Bureau of Reclamation knew about Sargent's motion, which was part of his homestead patent and probably the final reason the patent was approved (J. Sargent, 1907; U.S. Reclamation Service, 1907). The following statement of J. R. Garfield (1907), Secretary of the Department of Interior, pointed out this very important part of the patent:

"Claimant hereby further tenders to the United States Government any and all portions of said land that may be submerged by any reclamation works now contemplated, or which may hereafter be constructed, free of charge to the government, ...."

In any event, no condemnation occurred. The erosion problem was never resolved but only deferred to the future.

As early as 1938, another frustrating event occurred when Alfred became concerned that the National Park Service would condemn the AMK as part of a proposed extension of the Grand Teton National Park boundaries (O'Mahoney, 1938). Even though Alfred perceived a threat, there is no evidence that his property was ever proposed for condemnation.

Finally, the age old problem of county property tax assessments for improvements also surfaced for Alfred. His total assessment valuation increased $9,000 in 1939 over that in 1938 (Berolzhiemer, 1939c). Despite all of his protests, legal services and a Petition on Appeal in Teton County District Court, the issue was unresolved (Teton Co., 1940; Simpson, 1939).

Life on the AMK for the Berols was quite different from that of either Sargent or Johnson. Much of their time at the ranch was spent entertaining friends and visitors. Their general life-style "was a curious mixture of Eastern (even European) formal traditions and the free-and-easy style of the West" (K. Berol, 1986a). Their daily activities followed a well-defined routine (Jonak, 1984).

Between 1936 and 1969, the Berols average stay per year was 2-1/2 months, extending from about the last week in July until sometime in the first week of October. Prior to the mid-1960s, they generally traveled by train with their arrivals most frequently at Rawlins, Green River, or Evanston, Wyoming; however, one-third of their arrivals were at Gardner and Livingston, Montana. Their departures were usually from the Wyoming towns. In the mid-1960s, they began using air travel to reach the ranch. On most of these occasions, the caretaker transported them and their large amounts of luggage between the ranch and their various embarkation points (Diaries of V. Lawrence, 1936-68).

The Berols employed several caretakers during their ownership of the ranch. Slim Lawrence and his wife, Verba, served from 1936-71. Lee and Madeline Brendenstahl worked for Slim and the Berols from 1965-71. John B. Adams and his wife, Cheryl, were employed from 1971 until the property was sold to the Park Service. In 1968, Mr. Berol provided Slim Lawrence with a new house on the AMK property for his retirement years (V. Lawrence, 1967-68). Also, in an effort to provide suitable living quarters for the family of John and Cheryl Adams, the Berols in 1974 arranged for construction of a new prefabricated home just east of the Mae-Lou-Lodge (Adams, 1985).

In addition to the caretakers, the Berols usually employed a cook, two or three maids and a chauffeur-handyman for the times they occupied the lodge in the summer. The caretakers hired the seasonal employees and generally supervised their work. The chauffeur-handyman lived above the Johnson garage or in the Hogan 3-room cabin. The maids and cook were provided rooms off of the kitchen in the Berol Lodge.

One of the main jobs of the handyman was chopping and supplying wood for 10 fireplaces, a furnace and a variety of heating stoves. All of these employees usually reported for work before the arrival of the Berols to help clean the buildings, unpack and put in place the 68 Indian woven rugs and other valuable interior furnishings. Each item had its special place and the positioning of each item was precisely specified by the Berols (Jonak, 1984; Adams, 1985).

The maids and the cook were issued four uniforms which always had to appear clean, crisp and pressed. The maids served in a variety of capacities. As personal maids, they carried out the usual housekeeping chores according to a routine schedule. The private character of the Berols day to day life-style was such that they used the master bedroom, dressing rooms and Alfred's study for reading and relaxing. The living room area was mostly used for entertaining guests. As a consequence, the maids could only work in the private areas when the Berols were at meals or away from the lodge. For example, one of the maids had to slip away from the dinner duties to turn down the bed sheets in the prescribed manner.

At breakfast and dinner, the maids became waitresses and also helped the cook prepare the food. Alfred Berol always carved the meat and summoned the help by using a buzzer at the table. Alfred liked his meat blood red and everyone had to eat it that way. There was a set order in which things were brought to the table and served. Separate china settings were used for breakfast and dinner. A centerpiece of flowers or fresh fruit was always required (Fig. 51). During parties, the maids also served drinks to the guests (Jonak, 1984; Adams, 1985).

|

| Fig. 51. AMK Lodge dining room. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Even the menus were a product of a specific routine. Kenneth Berol remembered, "While my mother planned most of the meals, my father always discussed party-menus directly with the cook, sometimes to the discomfort of both mother and cook when 'routines' were violated" (K. Berol, 1986a). Guests at their parties knew they would be served either ham, leg of lamb or turkey, preceded by a scalloped half of cantaloupe with maraschino cherries in the scallops (Untermyer, 1978; Jonak, 1984; Adams, 1985).

Kenneth further recalled, "for house guests, there were printed cards in each room setting forth the time for meals (which were always punctual): Breakfast 8:30; Lunch-1:00; Cocktails-6:30; Dinner-7:15."

Alfred was a consummate reader, staying up until 2 or 3 a.m. to read. The 3,000-watt Kohler generator at the Mae-Lou-Lodge was unable to furnish power to both houses. Consequently, Alfred had a 15 KW 4-cylinder diesel generator installed at the north end of the barn. It ran 24 hours a day and furnished power through the first underground electric cable used in Jackson Hole (W. Lawrence, 1981). The diesel generator was retired in 1955 when Alfred had the Lower Valley Power and Light REA Company construct power lines to the ranch (V. Lawrence, 1951-55). With this new source of power, Berol also had electric baseboard heaters installed in the Mae-Lou and Berol lodges, markedly reducing the wood cutting efforts.

With all of their entertaining, Alfred did not want his guests or family to be inconvenienced with the failure of a water pump. Consequently, he had three interconnected wells drilled with separate pumps to serve as backup systems (W. Lawrence, 1978).

The Berols were socially inclined with as many as seven or eight guests staying at the AMK at one time. These friends were accommodated in the Mae-Lou-Lodge or the quarters above the garage (Jonak, 1984). Alfred loved parties; and at least in the early years at the ranch, they would have six to eight parties per month with 12-22 people in attendance (K. Berol, 1986a). One of the larger parties of the summer involved around 30 guests invited to celebrate Alfred's birthday on October 5 (V. Lawrence, 1956-60; 1961-65). A regular summer guest was publisher Alfred Knopf. Banker and friend, Felix Buchenroth, was a frequent local guest (Jonak, 1984). Several notable visitors included labor leader John L. Lewis and Wyoming Governor Nels Smith. Verba Lawrence (1951-55) in her diary sums up the frustration of the employees during 2 days in September, "No rides—too many house guests and fire places to watch.... More house guests arrived—No end to the company this summer—Another Dinner party at the Big house."

Since the private living area of the Berols was never shared with guests except for a few special individuals who were invited to Alfred's study (Fig. 52) (Untermyer, 1978), a guest bathroom facility was located off of the living room entrance. Despite the fact that many parties were held in September and early October, when the weather could be inclement, there was no hot water or heat provided for the guests in this facility even though it was in every other area in the lodge. As one frequent guest noted, "Stays in that bathroom facility were of very short duration."

|

| Fig. 52. Alfred's study, AMK Lodge. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Alfred loved to shoot both shotguns and rifles. During the Berols' first 20-25 years at the AMK, they invited many of their friends to participate in trap shooting and other types of shooting matches involving bench rests and offhand matches. Even though Madeleine didn't participate, she would faithfully attend those affairs with her husband. Alfred had a trap shooting range installed in the clearing to the east of the Johnson Monument and the Sargent cabin site. A 200-yard rifle range, complete with bench rests and a "dark tunnel," was located on the southwest side of Sargent's Bay. A combination 100-yard rifle and a 50-yard pistol range was located adjacent to the south side of the blacksmith shop and east of the present parking area. Sometime in the 1960s, Alfred ceased using their trap shooting range; however, he continued shooting at the Jackson Hole Trap Club.

During most of their first 10 years at the AMK, the Berols frequently provided day-long horseback trips for their guests into the forested area east of the AMK and the highway to Yellowstone Park. While Slim and sometimes Verba generally guided those trips, Esther Allan, wife of Forest Ranger Sunny Allan, remembered serving as a guide a few times. The horses for those trips were maintained in the fenced pasture near Arizona Lake (W. Lawrence, 1981; Allan, 1978). Both Alfred and Madeleine were good horseback riders and accompanied their guests on most of those trips. In addition, Madeleine liked to ride horseback with Slim Lawrence when he would explore or look for Indian artifacts (W. Lawrence, 1978). Unfortunately, after a back injury in the early 1940s, an operation in 1947 and complications afterwards, Slim was forced to give up horseback riding (W. Lawrence, 1980). About the same time, Alfred also gave up that activity because of a leg circulation problem (W. Lawrence, 1981).

Hunting was a natural extension of the horseback riding and the shooting activities of the Berols. Alfred hunted Sage Grouse around the Daniel area. As with Johnson, this was often combined with his antelope hunts to Sweetwater County with Slim Lawrence. They also hunted antelope on the Belden Pitchfork Ranch west of Meteetsee. John Wort and the Nelson brothers normally guided Alfred on his elk hunts in the Pacific Creek area. Alfred hunted bighorn sheep with Charles Nelson in the Crystal Creek drainage of the Gros Ventre Range. His bear hunting was usually done in the same Arizona Lake region where Johnson had also hunted bears (W. Lawrence, 1981).

In connection with his hunting, Alfred expressed his opinion about Wyoming's wildlife management and regulations in frequent letters to Richard Winger; Felix Buchenroth and W. L. Simpson of Jackson; Governor Nels Smith; and John Scott, Director of the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission (Berolzheimer, 1938-53). At one time, he developed a memo about his ideas which he sent to these men. The following (Berolzheimer, 1939d) is an excerpt:

"I favor very much the creation of areas restricted to the use of trophy hunters only for elk on special license, restricted naturally to bull elk only with the possible further proviso that no elk smaller than a five point could be shot in this area. I would further permit the shooting of buck deer only, bear and grouse in these restricted areas with this special license. The season in these restricted areas I would have from September 15th to November 1st only. This might result in attracting a considerable number of desirable Eastern hunters who bring the most money into the state."

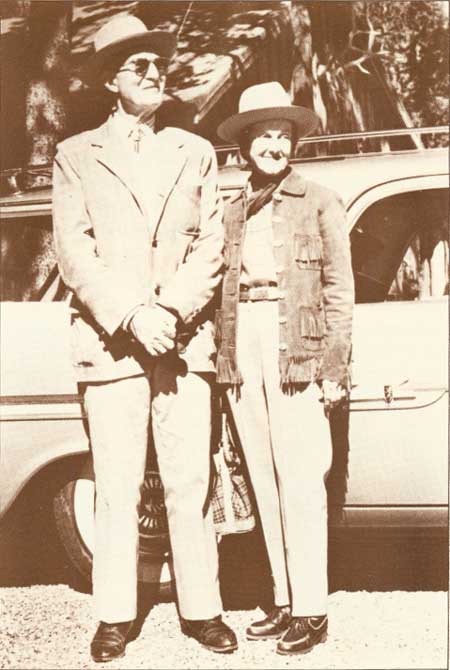

Like the Sargents, the Berol family was a paternally dominated one. Alfred appears to have been a man with highly contrasting and diverse interests and abilities (Fig. 53). Beginning with his early schooling, he maintained an active interest in literature, history and the fine arts. He became a trustee of the Columbia University Library and in 1970, was cited by the Friends of the Library for his service. Also, he was on the Overseers Committee of the Harvard University Library (N.Y. Times, 1974). He was considered a scholar and wrote about the literature and history of the 18th and 19th century England (Westminster College, 1963). As a collector with his wife, he donated rare paintings by various artists and letters by George Washington and by John Jay to Columbia University, as well as a letter of Galileo to Harvard University (N.Y Times, 1974). The New York Times wrote a complimentary article when Madeleine and Kenneth Berol donated Alfred's collection of Lewis Carroll's "writings, photographs, letters and memorabilia" to the New York University Library. "It was considered to be one of the best collections of Carroll that was still available in private hands here" (N.Y. Times, 1975).

|

| Fig. 53. Alfred Berol. (Berol Corporation Coll., Danbury, CT.) |

Alfred was also interested in agriculture, which included raising purebred Aberdeen Angus cattle at his Faraway Farm in Cross River, New York (Fig. 45). Besides his accomplishments in the family-owned business, he extended his industrial leadership by being a Trustee of the Stationers' Board of Trade and President of the Pencil Makers' Association. As a result of these scholarly and business activities, Alfred was presented an honorary degree, Doctor of Humanities, at the 1963 commencement exercises at Westminster College of Salt Lake City (Westminster College, 1963).

Alfred was hard of hearing, partly because of injuries incurred during his World War I service. Adjusting to this loss caused him to become unnecessarily irritated at times and to talk in a loud tone (Untermyer, 1978). In his correspondence on a variety of matters, Alfred displayed an ability to be understanding and diplomatic, as well as authoritative. He also could display the attitude that by reason of his position or status, he expected to receive special treatment and had no compunction in asking for it (Berolzheimer, 1938-53). As an example, in a letter to Richard Winger Alfred (Berolzheimer, 1938) protested against the method of obtaining sheep hunting permits:

"I made my application for a permit on November 4, 1937 for the succeeding year and mailed my check, and I am now informed that as more than 25 applications have been received, there will be a drawing on May 1st. I consider this eminently unfair and think that the method to be adopted should be first come, first served. Further more, it seems to me that a man who owns a home, such as I do on Jackson Lake, should have distinct preference over people who are not property owners in Wyoming."

Despite some of these traits, Alfred appeared to have the right personality to enjoy good relations with his business employees (Untermyer, 1978). Slim Lawrence enjoyed a fine working relationship with him (W. Lawrence, 1981).

In contrast to Alfred's temperament, Madeleine or "Mady" as her husband called her, was gentle, gracious and soft-spoken. Everyone who knew her described her in these terms. Her physical stature was petite and delicate, and she had long blond hair pulled back in a bun. She liked to wear western cut pants and a cowboy hat and was impeccably well-groomed at all times (Fig. 54). She was able to keep up with her husband in outside activities where she enjoyed horseback riding, swimming and tennis. She spoke fluent French and German. At times, she was intimidated by Alfred; but she was never known to have said an unkind word about anyone (K. Berol, 1986; Untermyer, 1978; W. Lawrence, 1979; Jonak, 1984; Adams, 1985). She always ran a smooth household, beautifully appointed, with excellant service. Alfred became her sole concern and there was little spare time after taking care of three households and servants and running his errands (Untermyer, 1986). After Alfred's death in 1974, she continued to live in their Hotel Pierre residence in New York City until her death in January 1985 (K. Berol, 1986).

|

| Fig. 54. Alfred and Madeleine Berol. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

As the only child, Kenneth's parents were strict with him and tended to be over protective when he was at the AMK (W. Lawrence, 1978). Kenneth arrived at the ranch when he was 11 years old and learned to enjoy the activities of his parents such as hunting, fishing and horseback riding. His association with the ranch was primarily during 1936-43. After that period, he or his family only visited for a few weeks each summer. Between 1961 and 1970, he was absent from the ranch (K. Berol, 1986a). Kenneth recalled, "As a child, I adored the ranch since it represented relative freedom from the 'stuffiness' of the East."

Kenneth had always been intrigued with the sea; however, it was on Jackson Lake where he learned to sail. "Capt." Mapes of Jackson Hole was his teacher (K. Berol, 1986) and sailing in a Snipe class sailboat was a special pleasure for him (W. Lawrence, 1980). This love of boating carried over into his adult years when he became a member of the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Clubs. His clubs include Stamford Yacht, Port Royal and Naples Yacht (K. Berol, 1986a). Kenneth had special praise for Slim Lawrence: "He taught me to love nature, respect it, but not to fear it. Those lessons learned in the mountains of Wyoming are necessary prerequisites for a mastery of the sea."

Kenneth's preparatory education was obtained at Milton Academy, Milton, Massachusetts (K. Berol, 1986). Following the tradition of his father, Kenneth obtained his Bachelor of Arts degree at Harvard University and continued at that institution, receiving a Master of Business Administration degree in 1950. He served in the Army during World War II for several years and met June Waterous of St. Paul, Minnesota, during that period. He married her on August 14, 1947, and they had two children, John Alfred and Margaret June (Fig. 55) (Who's Who, 1984-85). Kenneth's family enjoyed the AMK Ranch and took advantage of the outdoor activities, having remodeled one of the Hogan cabins as their summer home in 1972 (W. Lawrence, 1979; Adams, 1985). June passed away in 1983. Subsequently, Kenneth married Betty Brookfield, a widow from Kansas City, Missouri, in 1984 (K. Berol, 1986a).

|

| Fig. 55. Kenneth Berols family (l-r) John, Margaret and June, Jackson Lake. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Like his father, Ken had served in different capacities in the family Berol Corporation such as Vice President, Treasurer and President. In 1979, he became Chairman of the Board of Directors, carrying on the family tradition (Who's Who, 1984-85; Standard & Poor's, 1980-85).

Alfred Berol died on June 14, 1974, in Danbury, Connecticut, closing out 38 years of continuous summer residency at the AMK Ranch (N.Y Times, 1974). Kenneth Berol, as executor of the estate, deeded the property to the United States of America in 1976 for $3.3 million (Teton Co., 1976). The Berol Lodge and other buildings are now on the Grand Teton National Park's list of classified structures to be protected, a fitting memorial to the Berol family and their great love for the West.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

dough_gods/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 17-Jun-2011