|

GRAND TETON

A Tale of Dough Gods, Bear Grease, Cantaloupe, and Sucker Oil: Marymere/Pinetree/Mae-Lou/AMK Ranch |

|

LAWRENCE ERA

As one looks back on the history of the Sargent-Johnson-Berol ranch, none of the owners were able to enjoy life on it to the same extent as did William Cecil "Slim" Lawrence. As a young man, he had tried unsuccessfully to buy the Sargent ranch. That event appears to have been a blessing in disguise as he later related, his caretaker position with Johnson and Berol fulfilled a boyhood dream:

"'I first come up here and got stuck on Jackson Hole in 1912', Slim says, as he explains his first visit to Jackson Hole. 'I was only 14. I never could get it out of my mind. Then I moved up here to live in 1921. I wanted to live up here at this end of the lake where I could hunt and fish all I wanted and trap and do a lot of reading and be independent. It's just the job I wanted because I was by myself all the time. I done the work, of course, and always had it ready for 'em, and I've had a great life up here. Done what I wanted to do and made a good living'" (Teton Magazine, 1977).

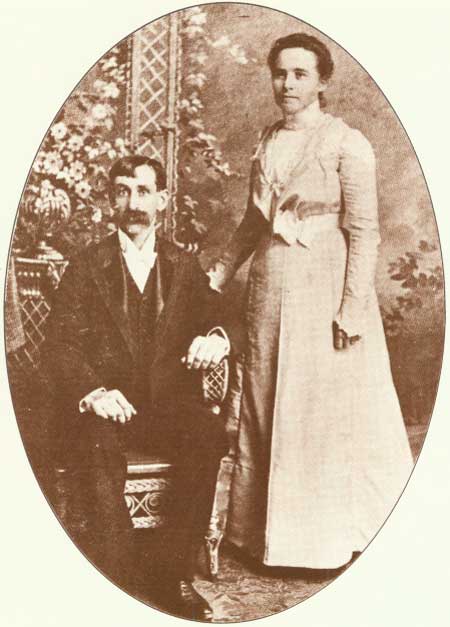

Like the Sargents, Johnsons and Berols, the Lawrence family ties were strongly Eastern, beginning in Yonkers, Westchester County, New York. The Lawrence name in Yonkers was old, descending from three brothers who came to the United States in 1635. Slim's father, Sidney Herbert Lawrence, was one of 12 children born to William H. Lawrence and Maria V. Back. He was almost a "New Year baby" being born, along with his twin brother, Cecil, on December 31, 1852 (Fig. 56) (Scharf, 1886; St. John's Church, No date). Sidney's father's occupation as a coroner was recorded in the U.S. Census (1860b) and in a later census, as a lumber merchant (U.S. Census, 1870).

|

| Fig. 56. The Lawrence twins, Sidney H. (l) and Cecil R. (r). (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

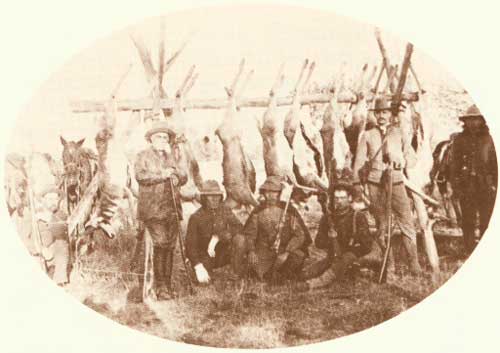

Three of the Lawrence brothers were drawn to the West, becoming successful game hunters to supply the markets in Cheyenne and Denver (Fig. 57). While the record is not clear, it appears that the twins, Sidney and Cecil, made trips to the West during the late 1870s; and Eugene, the youngest brother, joined them later in Colorado when they became settlers.

|

| Fig. 57. Wild game market hunters for Cheyenne, WY and Denver, CO markets: Cecil Lawrence, far left, and Sidney Lawrence, third from right. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Sidney was listed in the 1870 Yonkers Census as a grocer's clerk and in 1880 as a collector. The only reference to Sidney in the Yonkers City Directory was for the years 1877-78 when his occupation was listed as a planer (U.S. Census, 1870; 1880a; Yonkers City Directory, 1877-78). He was described as a small man, about 5 feet 6 inches tall and weighing 150 pounds (Laramie Daily Boomerang, 1912). Slim Lawrence remembered his father telling him about the wonderful Jackson Hole country and its abundance of game. Sidney had gone there in 1876, looking for game to supply meat for the railroad workers in Cheyenne, Wyoming (W. Lawrence, 1979).

Eventually, the Lawrence brothers settled in North Park, Colorado, which was surrounded by mountains and located in an isolated area near the border of Colorado and Wyoming (Fig. 58). Charlie Winscom, an early homesteader, listed "the Lawrence boys, Cid, Cecil and Gene" as settlers on the Canadian River in North Park in 1883-84 (Gresham, 1975). In the History of Westchester County, Eugene, Sidney and Cecil are mentioned as residing in Colorado in 1886 (Scharf, 1886).

|

| Fig. 58. Lawrences' North Park homestead, 1894: (l-r) Mrs. Cecil Lawrence, Elizabeth Schork, Sidney Lawrence, Charley Schork and Cecil Lawrence. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

In North Park, the brothers pursued many types of occupations in order to survive in this mountain region. They probably continued as meat hunters for:

"The country at this time swarmed with deer, antelope and elk and bear and mountain sheep were quite common.... it was the usual custom for many settlers in the fall of the year to kill enough deer, elk or antelope to make a wagon load and haul the meat to outside towns and sell it and bring back a load of ranch supplies" (Gresham, 1975).

Cecil was listed as the postmaster at Otis in North Park near Independence Mountain in 1881. Herb Hill, an early prospector, remembered the Lawrence brothers as staking a mining claim in the Lawrence Draw of Independence Mountain (Gresham, 1975). Sidney located the Last Chance Claim in the Independence Mining District in 1896 (Larimer Co., 1896). The Lawrence name has been given to many topographic features in that region and appears on recent USGS maps. Both Sidney and Cecil had a registered stock brand for Pinkhampton, a small settlement in North Park, which indicates they raised either cattle or horses (W. Lawrence, No date).

Sidney's twin, Cecil, had been married since 1874 (St. John's Church, 1874) and in the 1890s went back with his wife to Yonkers to join the family business. Also, it appears that Eugene, Sidney's youngest brother, married Elizabeth Margaret Schork who came to Pinkhampton with her brother, Charlie. (Later she married Sidney.)

Elizabeth, born in 1876, came to the United States from Germany with her parents in 1881 (U.S. Census, 1900a). Her father was a scissors maker, who worked in a factory in Elizabeth, New Jersey (W. Lawrence, 1980). The record of Eugene's marriage to her and events following are vague. Mabel, a daughter, was born in October 1896 (W. Lawrence, 1981; P. Lawrence, 1981; U.S. Census, 1900a; 1910a). No records could be found about Eugene after that time. Slim Lawrence remembered that his mother (Elizabeth) married another Lawrence in North Park who died (W. Lawrence, 1981). There's also some indication there was a divorce between Elizabeth and Eugene (W. Lawrence, No date).

Sometime in the late 1800s, Sidney began driving the stage out of Pinkhampton on the Walden-to-Laramie line (Laramie Daily Boomerang, 1912; W. Lawrence, No date). He also acquired property along with Lizzie Lawrence near Pinkhampton, which was a stage stop, post office and store (Jackson Co., 1894). After Eugene's death or divorce, Elizabeth Schork Lawrence married Sidney Lawrence on February 7, 1897 (Daily Boomerang, 1897; Albany Co., 1897). Following their marriage, they settled in Laramie where Sidney was employed to drive the 25-mile Laramie-to Woods Landing leg of the Trabing Brothers Laramie-to-Walden mail and stage line (Fig. 59) (Laramie Daily Boomerang, 1912; Laramie Republican, 1912). Their only child, William Cecil, was born in Laramie on August 31, 1899 (Fig. 60) (W. Lawrence, 1979; U.S. Census, 1900a).

|

| Fig. 59. Sidney Lawrence (l) and Trabing Brothers Laramie-to-Walden stage. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 60. Sidney Lawrence's family: (l-r) Elizabeth, Sidney, Mabel, Mrs. Schork (Elizabeth's mother) and William. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

After several moves, Sidney settled his family in their final Laramie home (Fig. 61) at Fourth and Thornburg Streets (The present Laramie City Hall stands on that lot which is now Fourth and Ivinson.) (W. Lawrence, 1979; U.S Census, 1910a). Because of Laramie's school enrollment and classroom space limitations, Slim's first and second grade school years had to be spent in the basement of the University of Wyoming's main building (W. Lawrence, 1980).

|

| Fig. 61. Lawrences' Thornburg home, Laramie, WY: (l-r) Elizabeth, William, Sidney and Mrs. Fred W. Phifer of Wheatland, WY, 1905. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Slim attended school in Laramie until sometime around 1910 (Fig. 62). About that time, Trabing's stage line lost its mail contract and Sidney lost his job. Ted Olson (1973) lamented the loss of Sid Lawrence and paid tribute to his dedication and service:

"But when I started school our mail was still being brought by stage, and dropped off where the Sodergreen ranch road joined the highway, a half mile beyond the school-house. It wasn't the kind of stagecoach you see in the movies, merely a big wagon with three seats. The driver was a weather-bitten, laconic man named Sid Lawrence. He made the thirty-mile trip between Laramie and Woods Landing six times a week, going out one day and returning the next, delivering and picking up mail, light cargo and a few passengers. He was true to the tradition of the service: neither rain, nor snow, nor dark of night stayed him from his appointed rounds.

Rural Free Delivery put Sid out of business. I recognize now that he was obsolescent, a victim of what economists later would call technological unemployment. But like many others displaced by supposedly more efficient ways of doing things he left a gap.

Now we had to ride five miles for our mail instead of two. Passenger service was terminated; if you fired a hay hand you couldn't ship him back to town on the stage, and only outrageous misconduct — like abusing a horse — justified making him foot it. So you didn't fire him. Sid had always been glad to do small errands. If you needed something urgently you could send in a note to the store and he would bring it out the next trip. The RFD man, being a government employee, couldn't be so accommodating; besides, his one-horse four-wheeled mobile post office had no room for any object bulkier than a mail-order catalogue.

We missed Sid Lawrence. It was some years before the telephone and automobile bridged the gulf his retirement had left."

|

| Fig. 62. Slim Lawrence and his friends, Cecil Ballard and Clarence Ovitt, Laramie, WY. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Slim Lawrence remembered riding with his father on the stage and curling up in a buffalo hide under the seat to keep warm (W. Lawrence, 1979).

Also around 1910, Sidney and Elizabeth separated (W. Lawrence, 1980; Albany Co., 1911). Sidney obtained work at the Baldwin Ranch (Fig. 63) on the Big Laramie River near Gleneyre, Colorado, just across the Wyoming border (Albany Co., 1911; Laramie Republican, 1912). While living on this ranch with his father, Slim attended a rural school at Gleneyre for 1 year. The children would ride horses or ski to school (W. Lawrence, 1979). At this time, Slim's stepsister, Mabel, was living with one of her relatives in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and attending school (W. Lawrence, 1980; Laramie Daily Boomerang, 1912). Elizabeth remained at the Lawrence home in Laramie where she continued renting furnished rooms (Polk, 1911) and was listed as a "nurse, at home" and having seven roomers in the Laramie U.S. Census (1910a).

|

| Fig. 63. Baldwin Ranch on Big Laramie River, where Sidney and Slim lived in the log cabin on the right. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Life on the Baldwin Ranch was a wonderful and at times painful experience for Slim. His father had given him a 25-20 rifle to use when horseback riding, cautioning Slim not to hold a loaded rifle while getting on a horse. Slim disregarded this advice and his loaded rifle fell and fired. Slim still carries the bullet in his side to remind him of the incident (W. Lawrence, 1979).

During the ranch stay, his father had taught him how to trap coyotes, bobcats, mountain lions and wolves. Also, he took care of the dogs that were used to hunt bears (W. Lawrence, 1979). A newspaper account in early 1912 described one of Slim's trapping adventures:

"Cecil Lawrence, the 12-year old son of Sidney Lawrence, of the upper Laramie river ranch had a very close call a few days ago with a big wolf weighing 130 pounds. The wolves in that section have been very bad this winter and everybody who has a wolf trap is setting it in the hope of catching some of the animals. Young Lawrence had a trap fastened to the fence with a chain and staple. Going to the trap one morning this week he found the large wolf enmeshed therein. The animal made a lunge at the boy, who threw a hatchet at lupus, but missed him. The wolf made another lunge and broke the chain, charging the lad, who threw his gloves at the huge animal and then ran. A dog belonging to Mr. Lawrence attacked the wolf from the rear and permitted the boy to escape. Summoning his father they armed themselves and started in pursuit, being able to follow the tracks of the animal and the marks of the trap and dragging chain, Mr. Lawrence killing the wolf with his gun. The boy had a very close call but showed his pluck and now has the pelt for a trophy."

In addition to selling the pelt, Slim collected his first and probably largest fur price because of a bounty levied on each head of cattle on the district's range which amounted to $400 (W. Lawrence, No date).

The Baldwin Ranch stay ended in tragedy. When his father did not respond to the ranch dinner bell, Mrs. Baldwin sent Slim to find his father. Slim discovered him dead in a corral with a jack stud mule. While there was no autopsy, the undertaker said the nature of Sid's injuries and broken bones indicated he had been kicked very hard and that was likely the primary cause of death (Abbott, 1912; Laramie Daily Boomerang, 1912). Unfortunately at this time, Slim's mother was sick in a Denver hospital. In this trying period, Slim was cared for by friends and ultimately was placed in a boy's boarding school in Denver (W. Lawrence, 1979). In the meantime, his father's remains were sent back to Yonkers for burial (Laramie Daily Boomerang, 1912a). According to the death certificate, Slim's father died on February 13, 1912 (State of WY, 1912).

The Denver boarding school stay was short-lived; for sometime in the Spring 1912, Slim ran away to Gleneyre where he stayed with the Schroeder family. Slim remembered that "they had 10 children so one more didn't matter." His education continued when his mother sent him to live with a friend in South Denver to attend the public school (W. Lawrence, 1979).

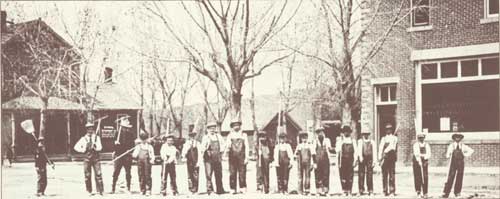

During this time, his mother was undergoing nurse's training, graduating from Cheyenne Private Hospital with honors on October 30, 1913 (Laramie Republican, 1913). In the summers, before her graduation, she worked with Dr. Phifer in the Wheatland hospital (Fig. 64). Even though Slim didn't like the town, he recalled two outstanding summer experiences there. Slim joined one of the earliest Boy Scout troops in Wyoming under Wheatland's Leon Goodrich. For a project, the scouts cleaned the town streets to earn money to go to Fort Laramie to hunt for arrowheads (Fig. 65). This collecting experience was likely one of the early influences which stimulated Slim's interest in Indian artifacts.

|

| Fig. 64. Elizabeth Lawrence (r) carrying Wheatland hospital laundry to Dr. Phifer's home for washing. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 65. Wheatland Boy Scout troop, 1912. Slim Lawrence, third from right. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Another long remembered experience was Slim's 1912 summer trip with the Kirk family, traveling from Rawlins to Jackson Hole and Yellowstone National Park using a wagon drawn by two horses, saddle horses, a cookbox on the back of the wagon and tepee tents for sleeping. He remembered camping near Sargent's cabin and meeting John. He also recalled the dust because of the water wagons and tourist coaches traveling at a trot (W. Lawrence, 1979). Despite the inconveniences, Slim thought many times of going back to Jackson Hole, not dreaming he would spend most of his adult life in the area where they camped by Jackson Lake.

All of the trials and tribulations of Slim, his sister and his mother culminated happily with his mother's marriage to a prominent resident of Rawlins, Frank Hadsell, on November 10, 1913, in Cheyenne (Figs. 66; 67) (Laramie Republican, 1913a). Slim's stepfather was a remarkable man. He was born in 1852 in Hancock, Massachusetts, on the family homestead acquired from the Crown of England. As a teenager, he learned the butcher trade from his father and at 17, he was a partner in a Rhode Island butchershop. In 1872, he moved to Traer, Iowa, where he successfully ran a mercantile store. In 1880, he came to Wyoming where he became involved in horse raising and then sheep ranching which developed into one of the oldest sheep companies in Carbon County, Wyoming. Hadsell moved to the town of Rawlins in 1888 and maintained the sheep business from a ranch near Green Mountain, north of Rawlins. On May 27, 1920, he was appointed Warden of the State Penitentiary at Rawlins (WY Bd. of Charities and Reform, 1920) and became inactive in the sheep business; Kleber, his son by a former marriage, had already taken over the management of the ranch.

|

| Figs. 66 and 67. Slim, Mabel and Elizabeth Lawrence (top, left); Frank Hadsell (bottom, right). (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Hadsell's activities were not solely confined to ranching. He served as Carbon County Sheriff between 1889 and 1893 and was appointed as a U.S. Marshal from 1899-1908. In addition, he was elected to the 1911 Wyoming Senate (Rawlins Republican, 1927; Daily Times, 1971). When Frank Hadsell died on October 18, 1927 (State of WY, 1927), his friend for 45 years, Rubie Rivera (No date), was prompted to pay tribute to his close friend:

"I have eaten and slept with him on the ground, in pullman cars and in hotels. He enjoyed them all for he was a real fellow. He was a friend of dumb animals and a very good judge of stock. He was a charitable man. Many poor families and old friends and children were benefited by his help but you never heard him even mention the fact that he had helped anybody. As an entertainer Hadsell might have had equals but there was never any better. He had a wonderful memory and his ability to tell old time stories or carry conversations on any subject was an enviable characteristic. His home was always open to his friends.

It was generally known that Hadsell was possessed of a mean temper. He was of a high, quick, temperament through no fault of his. He was born that way. But he was also endowed with what I call good judgement and could apologize to a fellow if in his judgement he was satisfied he had offended and was in the wrong....

Mr. Hadsell was a high class man. One who could make friends easily, he had thousands of them and seldom lost a friend. When he did there was a reason for it and Hadsell could never forgive his lost friends. For this man knew himself and was always right. I don't wish to say that he was perfect but he was close to it in my estimation.

He had brains way above the average man and would use them either in an emergency or he could deliberate and plan most any transaction generally to the satisfaction of all concerned. He was fearless as an officer yet he had personality and magnetism and was very convincing."

Because of the dynamic personality of his stepfather, Slim Lawrence likely acquired many traits and skills under his guidance.

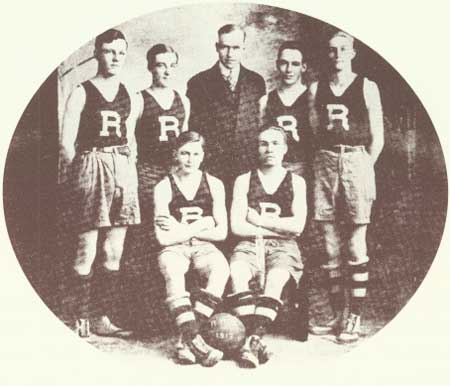

Slim finished high school in Rawlins, an environment he found more to his liking than in Denver. Even then his height was a useful resource as he played center on his school's basketball team. In addition, he was a member of the baseball and track teams (Fig. 68) (W. Lawrence, 1980; 1979).

|

| Fig. 68. Slim Lawrence with Rawlins High School basketball team, ca 1916. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

The Hadsell Green Mountain ranch afforded Slim an opportunity in the summers to live a life he had grown to enjoy with his father. He was able to acquire hands-on experience in a wide range of ranch work. Also, Slim recalls learning a new way of hunting coyotes and wolves by using greyhounds raised on the ranch. While herding sheep, Slim was impressed with the amount of jade in the area and returned later in life to pursue one of his hobbies of collecting rocks. One old timer, Cal Lemon, taught Slim about freight wagons and handling teams of horses. Slim accompanied Cal as he hauled sheep wool from the ranches to the railroad. Cal would let Slim ride one of the wheel horses and handle the jerkline when the road was smooth. Meanwhile Cal would sip his whiskey and sleep on the load (W. Lawrence, 1979).

Another influence was Oscar Kipp, head of the sheep operation for the Green Mountain ranch (Fig. 69). Slim credits Oscar for teaching him the fundamentals of the sheep and ranch business, information which became invaluable in future years.

|

| Fig. 69. Oscar Kipp at Hadsell's Green Mountain ranch. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Slim's curiosity led him to participate in the Farlow Wolf Roundup on August 13, 1917, even though his stepfather had opposed participation in the drive. This was a 3-day affair with participants arranged in a circular pattern riding towards a common center covering 1,600 square miles. Fires were built at night to keep the predatory animals inside the circle. The area involved stretched from Riverton through parts of the Gas Hills and the Rattlesnake Hills. This highly publicized event had 17 companies consisting of 30-40 horseback riders each. After the drive, there was a dance and Wild West events for prizes. Numerous coyotes, 3 wolves, 1 bear, many game animals and rattlesnakes were killed by the participants (Lawrence, 1979; 1980).

Sometime in late 1917 or early 1918, World War I fever caught up with Slim and he enlisted in the U.S. Navy for training as a hospital corpsman at a Pacific Coast base (Fig. 70). That training assignment was changed and he was transfered to a ship as a fireman trainee. He was ultimately assigned to a troop transport ship; however, after serving a short time, he was discharged on April 1, 1919 (W. Lawrence, 1979; No date).

|

| Fig. 70. Slim Lawrence with his close friend, Carl Krueger. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Between his discharge from the Navy and 1921, Slim tried a number of different jobs. He served as a crew member on a private ocean freighter on a round trip to England and France. Back in the U.S., he was employed as part of a crew spraying weeds from a train along railroad tracks from San Francisco to Sacramento, California, and Portland, Oregon. Finally, Slim unexpectedly met his old friend from Hadsell's Green Mountain ranch, Oscar Kipp, in California. Oscar, now associated with the Yellowstone Sheep Company, gave Slim a train ticket back to Wyoming and immediately hired him to work for that Company (W. Lawrence, 1980).

During more than a year's employment by the Yellowstone Sheep Company headquartered at Arapahoe, Wyoming, Slim was in charge of the Lander area flocks. Those flocks, tended by Mexican herders, were summered in the Wind River Range from Fort Washakie and the Little Wind River to Bull Lake Creek and were wintered in the Pavillion area north of Riverton. This meant much of his summer was spent living in a tepee tent and traveling with a saddle horse and a pack horse. Bear predation was a major problem on that summer range, causing Slim to kill many of them. Because of a decline in the sheep business and an anticipated failure of the Yellowstone Sheep Company, Slim decided it was time to do something else (W. Lawrence, 1979).

During his employment with the Yellowstone Sheep Company, Slim got to know a number of people in Hudson, Lander and Riverton. Consequently, it was not surprising that Slim's next major job was with the Lander-Yellowstone Transportation Company. This company was formed to serve the Amoretti Hotel and Camp Company, as well as to carry mail between Lander, Crow heart, Dubois and Moran. While it is not clear who owned what, H. O. Barber of Hudson coal mining fame, Eugene Amoretti of Lander and J. T. Gratiot of the Diamond G Ranch (Brooks Lake Inn) appear to have been the major investors in all or part of these enterprises. In 1924, the Jackson's Hole Courier announced, "The Amoretti Company is going into the tourist business on a scale that indicates that they have great faith in this part of the west as a summer playground."

The Amoretti Company included the Amoretti Inn near the present site of the Jackson Lake Lodge and seven tent camps located at the South Fork of the Buffalo River, Soda Fork, Two Ocean Pass, Fox Creek, Harebell Creek, Heart Lake and Lewis Lake. These tent camps were in the Teton National Forest or in Yellowstone National Park under a special use permit. All of the tent camps, except Lewis Lake, could only be reached by horseback. As a result, at one time Amoretti operated with 300 head of horses (WY State Journal, 1974; W. Lawrence, 1979; Jackson's Hole Courier, 1924; 1926).

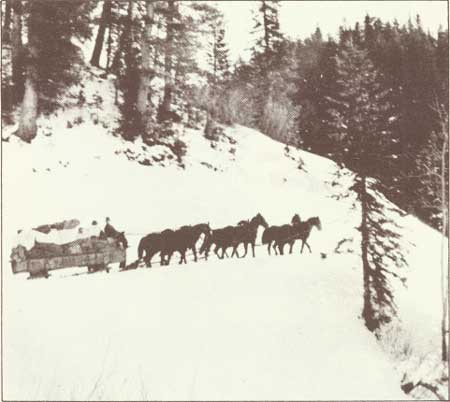

Slim returned to Jackson Hole in 1921 as a driver for the Lander-Yellowstone Transportation Company (Teton Magazine, 1977). Before he could begin work, he had to wait for the company's new Graham bus to be brought over Teton Pass from Idaho by horse-drawn freight sled in winter (Fig. 71). Only one vehicle could be loaded and hauled per day. Since Slim was 10th in line, he spent 10 days working for Harold Scott at his Teton Pass "lunch and change of horses" station waiting for his bus to be delivered. Much of that first summer he traveled in Yellowstone Park with H. O. Barber promoting travel to Jackson Hole. During his bus driving years, Slim had two buses, the Graham and then a White Motor Car on a 3/4 ton chassis (W. Lawrence, 1979; 1981).

|

| Fig. 71. Harry Scott's mail and freight sled on Teton Pass. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Even with these new vehicles, the trip to transport tourists from Lander initially took 2 days over dirt roads. From Lander (the end of the railroad) the road passed through Fort Washakie over a bad stretch to Ethete, the Diversion Dam, Sand Draw, Lenore and the Wind River-Dinwoody Creek crossing. They had lunch in the Welty dining room in Dubois and stopped overnight at Brooks Lake Inn (Fig. 72). On the second day, they could travel either below Barber Point on a stretch of black gumbo road or on the upper Barber Point road which was in bentonite (Fig. 73). Both routes were equally exciting and when wet, frequently required Slim to put chains on all four wheels. From there the road passed by Wind River Lake over Togwotee Pass to Turpin Meadow (Fig. 74). From Turpin, the route traveled along the north side of the Buffalo River to the old bridge at the Blackrock Ranger Station, to the Hatchet Ranch and on to the Amoretti Inn near Moran (Fig. 75). By the mid to late 1920s, the Lander-Moran road had improved to the extent Slim could make the entire trip in 1 day (W. Lawrence, 1981; Teton Co. Hist. Res. Center, 1979).

|

| Fig. 72. Slim's bus at the Diamond G Ranch (Brooks Lake Inn). (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 73. Slim's bus on the Upper Barber Point Road. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 74. Slim's bus, Mrs. Roy White, Slim and Mrs. White's son in front of the Turpin Meadowstore, 1926. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 75. The Jackson Lake Lodge, formerly the Amoretti Inn, July 28, 1929. (Dan W. Greenburg Coll., Acc. No. 1642, Photo File W 994-t-jh-jll, "Jackson Lake Lodge." Archives Div., Amer. Heritage Center, Univ. of WY, Laramie.) |

The informality of the job allowed Slim the opportunity to engage in diverse activities. Each spring, logs were floated down the Wind River from the winter logging areas to the sawmills in Riverton to be made into railroad ties. To the delight of his passengers, Slim always carried his logging boots and a pike pole and would stop and join in with the tie hacks working the floating logs (W. Lawrence, 1980). The postmistress at Crowheart frequently gave Slim pie when he brought the mail. Returning the favor, Slim bypassed the Dubois post office and brought the mail to be canceled at Crowheart. Since the postmistress' salary was based on the amount of mail canceled at her post office, this was of considerable benefit to her. However, postal inspectors took a dim view of this and Slim had to cease that practice.

While in Jackson Hole during his employment as a bus driver, Slim stayed in one of Ben Sheffield's Moran cabins and kept a horse at Ben's stables. In return, Slim worked for Sheffield by punching cattle, hauling wood and serving as a fishing guide and butcher (W. Lawrence, 1979).

During the off season, Slim's diverse talents and self-confidence provided him many other employment opportunities, some successful and some not so successful. Besides the odd jobs around Moran, he guided hunters in the fall and worked as a tool dresser sharpening drill bits in the oil fields. One winter he worked for the Ohio Oil Company laying an oil pipeline from Coalville, Utah, to Green River, Wyoming. He helped hire draft horses from the surrounding ranches and locate the pipeline route. Usually he was done by noon and spent the rest of the day hunting mountain lions in the Coalville mountains (W. Lawrence, 1980; 1981).

Besides these jobs, Slim became involved in a variety of cooperative ventures, some of which took him back to Rawlins. One of these was a fur buying company which bought and sold fur, cattle hides and sheep pelts from ranchers in the Rawlins and Saratoga areas (W. Lawrence, 1981). In another venture, he and five friends filed on grazing land where the town of Sinclair now stands. They had heard about an oil company's interest in the area and speculated on it being a site for a tank farm. Slim and his friends proved up on the property with only one roll of barbed wire; consequently, they would keep shifting the fencing around on their different grazing claims to show improvements. Only after they sold their lands to Producers and Refiners Oil Company (now Sinclair Oil Company) did they realize they had sold their land at lower tank farm prices rather than the prices for a refinery which was to be built there (W. Lawrence, 1979; 1980).

He had more lucrative employment when his stepfather, Frank Hadsell, needed Slim's help at the penitentiary for short periods. Those penitentiary jobs included care of the cell keys at night, escorting a prisoner to California, inspecting packages, bringing prisoners from other jails to the penitentiary and even helping round up an escaped convict (W. Lawrence, 1979; 1980).

Another profitable enterprise with a partner, Jules Farlow, was leasing the Yellowstone Sheep Company's dipping vats for 1 month during 2 years (Fig. 76). About this time, Wyoming passed a law requiring all sheep to be dipped once a year for ectoparasites. Unfortunately, the state soon repealed the law and the dipping vat business was dissolved (W. Lawrence, 1979).

|

| Fig. 76. Yellowstone Sheep Company's dipping vats. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Several business ventures took him far away from Wyoming. In 1925-26, he and several Rawlins friends took several White freight trucks to Florida in another speculation enterprise. This time they hoped to cash in on a building boom by hauling lumber to Florida from as far away as Tennessee. Unfortunately, that enterprise was a financial failure. A more successful venture with his friend Jules Farlow, was a movie contract in Hollywood. These men spent about a month in Hollywood as managers for 50 Indians in the filming of the movie "Iron Horse" (W. Lawrence, 1980; Riverton Ranger, 1966).

Coincident with Slim's enlistment in the Navy, he married a high school classmate, Dorothy M. Evans, on December 28, 1917 (Arapahoe Co., 1917). They had one child, Shirley Louise, who was born in Denver on June 12, 1919 (W. Lawrence, No date). Unfortunately, the marriage ended with a divorce on January 8, 1921 (Carbon Co., 1921). His daughter, Shirley, married and had three children (Fig. 77). She died relatively young in Portland, Oregon, on June 17, 1971 (State of OR, 1971).

|

| Fig. 77. Slim and his daughter Shirley. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

One of the social events that attracted the young Jackson Hole bachelors was the dances held at various ranches and communities in the area. Slim met Verba Mary Delaney at a dance held in the old Kelly, Wyoming, store.

Verba was born in Dedham, Iowa, on June 12, 1905, to Joseph and Sarah Lewis Delaney (Fig. 78). When Verba was 1 year old, the family moved to Teton Valley on the west side of the Teton Range and settled on a ranch 5 miles from Driggs, Idaho. Verba's mother was 47 when she died in 1919, which caused some hardship for the large family. Even in 1967, Verba remembered her mother on February 7 and wrote in her diary, "My mother's Birthday—We had her with us such a short time, I wonder often how different life would have been if we could have had her longer." In the summers, starting in 1921, Verba worked for different families in Jackson Hole. She first was employed by the Edicks of Kelly and then the Frews of Moose, ending up at Ben Sheffield's Teton Lodge in Moran as a waitress around 1923-24 (W. Lawrence, 1981; No date; Jackson Hole Guide, 1970; V. Lawrence, 1967-68).

|

| Fig. 78. Joseph and Sarah Lewis Delaney. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Verba's contacts with Slim became more frequent when she stayed in Moran. Her love of the outdoors and history provided a point of common interest. In another context, Slim humorously referring to an old gas lamp said,

"Well, that's how I won my wife. The girls down at Sheffield's old lodge at Moran had 75 of them to pump and fill up with gas every night. So I used to go over and help them" (Teton Magazine, 1977).

One way or other, Slim must have impressed Verba and their friendship culminated with their marriage at Wind River, Wyoming, on September 20, 1929, with the well-known Reverend John Roberts officiating (Fremont Co., 1929).

As previously stated, William Lewis Johnson hired Slim Lawrence as his caretaker in December 1929, completely fulfilling Slim's dream of a settled ranch life in Jackson Hole. Slim and Verba lived at Sheffield's that winter and moved into the Johnson Mae-Lou-Lodge on May 9, 1930 (W. Lawrence, 1979).

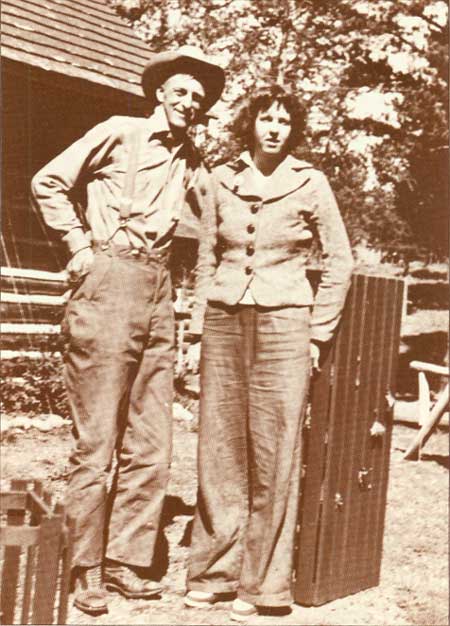

Over the next 40 years, as caretakers for Johnson and Berol and in their personal lives, Slim and Verba were able to enjoy a unique life-style (Fig. 79). Their life on the ranch consisted of several different stages. Initially, the years from 1930-42 were characterized by marked winter isolation and heavy physical exertion at work and during winter travel for supplies, mail, trapping and even social activities. Also, they were able to enjoy relatively unconstrained outdoor activities largely due to the low number of residents and visitors in the north end of Jackson Hole.

|

| Fig. 79. Slim and Verba at Johnson's Mae-Lou-Lodge, 1932. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

From 1942-54, the degree of winter isolation was sharply reduced by increased plowing of roads and development of mechanized oversnow vehicles. Also, Slim's physical activities were reduced because of serious physical injuries. Furthermore, after World War II, there was a marked increase in recreational use of the general area by people from outside Jackson Hole. Lastly, during this period, the extension of Grand Teton National Park severely limited the kind of land and resource use the Lawrences historically had available to them.

From 1954-67, Verba served as Moran's postmistress, which reduced her activities at the ranch and the amount of time she could spend with Slim. Slim had further physical limitations on his outdoor activities resulting from his old back injuries. Also, the establishment of the Jackson Hole Museum required much of his time, further reducing those activities they had traditionally conducted together. Their isolation and tranquility at the ranch essentially disappeared with the increased visitor use of Grand Teton National Park. It was in this period that they consistently spent their winters outside of the ranch.

Finally, 1967-71 represented a time of winding down during retirement. Unfortunately, the period came to an abrupt close with the untimely death of Verba.

Until the 1950s, the Lawrences' nearest neighbors for most of the year were at Moran or the South Entrance to Yellowstone National Park, about 10 miles south and 16 miles north, respectively. Consequently, they had to rely heavily on each other to carry out routine chores. It was here that their ranch backgrounds became so important.

Six months of the year they had to contend with cold, snowy weather. During their first 5 years on the job, their water system was shut off in early December until the middle of April. This necessitated using an outhouse. Turning the water on in spring was a time of elation, for it meant a bath could be taken in the bathtub instead of a galvanized wash tub (V. Lawrence, 1931-35). In the winter, water could be obtained only by melting snow or hauling it from the lake. On wash days, Slim recalled he used a wooden neck yoke to carry two pails of water from Jackson Lake which was over 200 yards away. He would make 10-20 trips during each wash day (W. Lawrence, 1981). In 1936, these winter problems were eliminated when Berol had the water system reworked and winterized (V. Lawrence, 1936-40).

Verba liked to hang her clothes in the sun to dry. Consequently, she frequently had to use snowshoes to hang out the clothes. Also, the clothesline height could be adjusted according to snow depth by using hooks Slim had put at different levels on the trees (W. Lawrence, 1981).

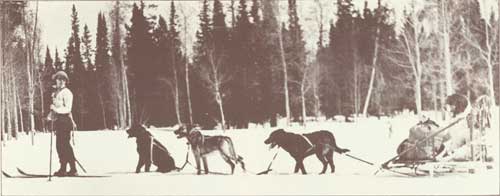

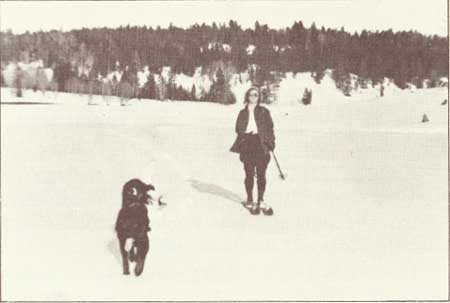

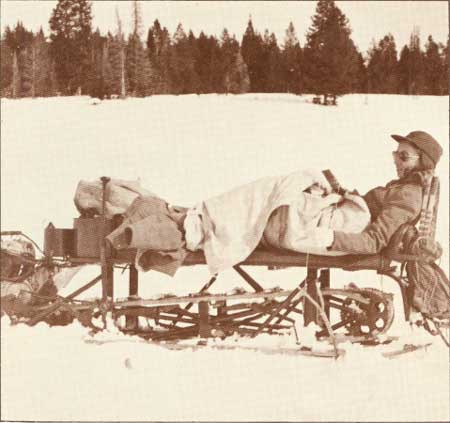

Usually the snow depths would be such by mid-December that wheeled vehicle travel into the ranch was impossible and closed the road until late April or early May. Therefore, the most reliable form of transportation in winter was snowshoes or skis. It was common to travel 15-20 miles a day on these and Slim and Verba used both. However, they also used a three or four dog team to pull a sled (Fig. 80). At the same time, depending on snow conditions, one dog would pull Verba on skis (Fig. 81). Once trails were packed, this was a good mode of transportation to facilitate hauling supplies (V. Lawrence, 1931-35; 1936-40; 1941-45). Locations of the trails followed were identified by willows that Slim stuck in the snow (W. Lawrence, 1979).

|

| Fig. 80. Verba and the Lawrences' dog team and sled. Cap is riding in the sled because he was bitten in the foot by one of the other dogs. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 81. Verba on skis being pulled by a sled dog. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Their dog team consisted of an Irish setter lead dog, a Lewellyn setter-collie cross and a mixed breed dog. Slim preferred these dogs because they were good pulling animals with amiable dispositions.

Travel with the dog sled did have its hazards. The sled trail was a convenient place to walk for moose. When the dogs and the moose met, they frequently took exception to each other with unpredictable results. On one such occasion, Slim was traveling the narrow swamp road trail to Moran and met a moose and her calf. During the encounter, the cow moose jump ed over the sled, kicked and hit the sled and severely damaged it (V. Lawrence, 1936-40).

The Lawrences made their own dog food by combining cracklings (bought in 100 lb. sacks) with their homemade corn bread. The dogs also got bones of wild game when available (W. Lawrence, 1981).

Getting to the outside world in winter was a chore for the Lawrences. The Jackson Hole News (1976) related,

"It took one day to snowshoe to Moran, another to take the mailsled to Jackson, and another to go over Teton Pass to Victor to catch the train to Pocatello. After spending four days getting to Salt Lake City, Slim told the taxi driver to slow down when he was driving 30 miles an hour. 'It felt like 100 miles an hour to me,' Slim recalls."

Later the Lawrences kept a car in Moran. At one time, they had to use some ingenuity to get a snowbound vehicle out to the highway from the ranch. In the Spring 1954, a trip to the Southwest was planned. In order to get their snow-bound jeep to Moran, Slim put on long hub bolts and four more tires and took it out on the snow crust early in the morning (W. Lawrence, 1981).

Motorized oversnow vehicles were just making their debut in the 1940s and helped to alleviate some of the primitive travel methods. In July 1941, Slim bought one of the earliest motorized toboggans produced by the Four Wheel Drive Company (Fig. 82).

|

| Fig. 82. Slim and Verba on Four-Wheel Drive motorized toboggan. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

As with all prototype models, some adjustments and modifications had to be made. However, this machine seemed to have more problems than its share. As Verba remarked (V. Lawrence, 1941-45), "it is a pusher type too. I'm the pusher." Again a couple of years later, . . . Cecil has worked on the motor toboggan for two or three days it should work, it gets good care." Besides the breakdowns, the major problem, which was never solved, was the snow spray which engulfed all of the toboggan occupants.

After 5 years and numerous modifications of two different machines, Slim and Verba sold their motorized toboggan and bought a snowplane in July 1946 (Fig. 83) (V. Lawrence, 1946-50). Certainly the snowplane was faster and much warmer than the toboggan, but it too had its drawbacks. It operated well on level surfaces but could not negotiate hilly, uneven terrain. The engine and propeller were noisy. Also, the metal runners frequently froze in the snow when parked, requiring considerable force to free them.

|

| Fig. 83. Lawrences' snowplane, March 1952. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

In order to solve the problem of impassable roads in the spring, Slim would furnish shovels for the Moran community's annual road opening. Trucks were furnished and everyone would gather to open the Jenny Lake road first, then the Yellowstone road, finishing up with the Togwotee Pass road (W. Lawrence, 1981).

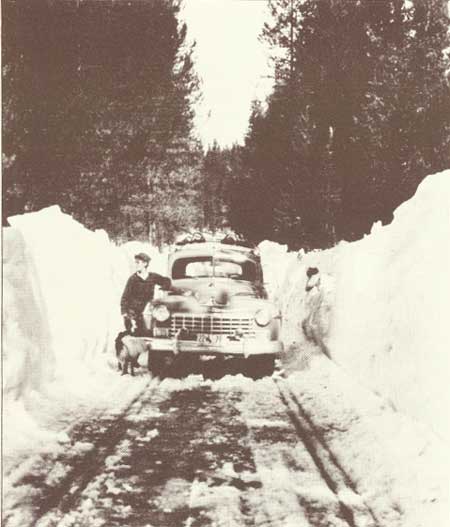

Following the enlargement of Grand Teton National Park in 1950 and consequently the increased plowing, snow closures of roads diminished sharply. The ranch road to the highway was the only remaining problem (Fig. 84). To cope with this, sometime in the 1960s, the Lawrences purchased two small double-track Ski-doos. These proved to be the long sought-for solution to their oversnow travel problems.

|

| Fig. 84. Verba on freshly plowed road into the AMK. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Most of the travel to Moran was for the mail which was the Lawrences major source of information and communication. The Jackson Hole Guide (1971) recounted,

"Lawrence remembers one winter when there was no mail for three weeks. 'I packed home 21 Denver Posts,' he said 'and read every one in order.'"

Slim and Verba also received many books and periodicals through the mail. The Jackson Hole Guide (1971) further interviewed Slim:

"The isolation of snowbound winters never bothers him the way it does some people. 'They don't know how to read,' he said. 'Living out like this you have to learn to read. A good book is lots of company.'"

Later in 1974, the Jackson Hole Guide commented, "Slim's extensive library is enough proof that he is an avid and thorough reader and researcher ...."

During the winters 1947 through 1950, the Lawrences began to spend the season in and around Moran where they had ready access to their car and plowed roads. Initially, reasons for these moves centered around Slim's back problems and the associated restrictions on his oversnow winter travel. They spent the winters 1951 through 1954 at the AMK. Once Verba became postmistress in 1954, they moved to Moran again in the winters. At first, they stayed in cabins in Moran and at the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's work center at the Jackson Lake Dam. Beginning in 1960, they stayed in an apartment at the Jackson Lake Lodge. They did not spend another winter at the AMK until they had their new house built there in 1968.

The weight of snow on the ranch building roofs could seriously damage those buildings and was a concern for the caretaker. As much as 3 feet or more of snow could fall in a single storm. This snow accumulation not only required bracing of the roof structures, it also required shoveling snow off of them. The steep nature of the Johnson Lodge roof was both an advantage and a hazard: snow could slide off under the right conditions. However, so could the snow shoveler as Verba described (V. Lawrence, 1951-55), "Slim came off the roof in a slide." In 1940, Slim began using a surveyor's chain tied to two long pieces of rope to cut the snow loose from the roof (V. Lawrence, 1936-40). This worked so well that it is still being used today. Usually the roofs had to be shoveled three or four times a winter, as well as shoveling to open up window areas and walkways covered by roof snow slides (Fig. 85).

|

| Fig. 85. Verba shoveling snow off of Johnson lodge, 1936. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Another annual winter chore in the 1930s was putting up blocks of ice for refrigeration. Part of the boathouse was insulated with sawdust and the ice was cut from Jackson Lake and stored there for summer use (Fig. 86). With the advent of electric refrigeration, this chore was happily eliminated.

|

| Fig. 86. Cutting ice on Jackson Lake for AMK icehouse. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Both Slim and Verba thoroughly enjoyed their solitary life on the ranch. As one reads through Verba's yearly diaries, 1931-68, the Lawrences never seemed to have any periods when they suffered from boredom. Even those times when Slim was away from the ranch, Verba methodically combated loneliness by working at staying busy. On October 29, 1955, their installation of a TV set further mitigated winter isolation.

Both Verba and Slim liked to ride horses. Since horses were always available on the ranch, they used them to carry out a wide variety of activities. Saddle horses were used for travel as long as the horses could comfortably buck the snow (V. Lawrence, 1931-35; 1936-40; 1941-45). The degree that Verba enjoyed riding is best expressed by her diary statement (V. Lawrence, 1946-50):

"Took Boone and Socks to the pasture for a week while I catch up on my house work. Heck with housework if I have a horse around."

The horses were particularly important for Verba during the hectic times when the Berols were at the ranch. Having a horse available allowed her to slip away quickly for some peaceful relaxation. The Berols' summer stays were trying at times for Verba as she wrote (V. Lawrence, 1936-40),

"Well here they are, such a 'hub ub' .... Up to the big house most of the day, I'm so tired just from so many around.... Oh for the peace and quiet of a good, long winter."

While horses were utilized extensively for hunting, artifact searching and trapping, Slim and Verba also used them for the pure enjoyment of the wilderness setting. The Lawrences' feeling of companionship with some of their horses on these trips was revealed by Verba (V. Lawrence, 1956-60):

"Felt heart-broken, Boone is gone—the best friend I ever had. I went hunting everywhere I went Boone was with me . . . he has packed me over every trail and mountain near here. I'll never forget him."

Trapping fur bearers was an important supplemental source of income to many Jackson Hole residents until the expansion of Grand Teton National Park in 1950. To preserve order, specific trapping areas were assigned by permit by the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission. Even so, each trapper was secretive about the location of his traplines and the nature of his trapping operations.

Slim obtained Bob Grimmesey's trapping area in the Arizona Creek drainage, which included the area north of Pilgrim Mountain, west of Pilgrim Creek, east of Jackson Lake and Arizona Creek and bounded on the north by Brown's Meadow. Slim had no trouble with other trappers and stated, "I minded my own business." Also, Slim worked closely with Herb Whitman who had the adjoining trapping area (W. Lawrence, 1981).

Until she married Slim, Verba had never done any trapping; however, with Slim's help she quickly became quite proficient. Together they operated two traplines with about 150 traps plus some irregular sets at a few special spots. Each trapline was about a 10-mile round trip which could be covered in 1 day and was checked several times a week. Verba could do both of them alone in the winter. An extension of the traplines to Brown's Meadows was not permanently maintained. Because of the length of the trip, Slim would set the traps on the way to the Meadows, stay overnight and spring the traps on the way back.

Saddle horses were used to run the traplines until snow depths made that impossible. Then snowshoes or skis were utilized. The dog sled was never used because of the scent the dogs left. Usually, the motorized toboggan, the snowplane and the Ski-doos were not practical because they were too noisy and too difficult to use in the terrain and timber of the area (W. Lawrence, 1981).

While many trappers used secret concoctions for scent and bait, Slim and Verba used a simple preparation for most of their trapping. In the spring, they acquired spawning suckers in Arizona Creek and Arizona Lake. Those suckers would then be placed in a jar to decompose in the sun over the summer. The oily residue was then used in the fall as the bait scent.

Their major trapping efforts were directed at pine marten and coyotes. They never trapped for beaver because of the difficulty in skinning them. Except where restricted by specific seasons, they trapped from October to early April, with their greatest effort being concentrated from November through January. Generally, the quality of the fur for marten was best in the months of November and December.

During the years of their trapping, the larger adult male marten appeared to prefer the higher elevation riparian areas; whereas, the females and younger males were found in the lower elevations around the ranch and along the lake shore. The Lawrences tried to avoid trapping the females. Coyote pelts were best before the snow crusted; once crusting occurred, the coyotes would lose large tufts of hair when they sat on their haunches and the hair adhered to the snow.

Marten trap sets involved placing a log for a runway against a tree in the fashion as shown in Fig. 87. The upper end of the log was flattened as a surface to hold the trap. The scented bait was attached to the tree above the trap and just out of reach of the marten. The catch was made when the marten's front feet dropped down to the trap. The trap was set in such a manner that it would fall off when tripped, swinging the captured marten away from the tree to avoid getting pitch on the fur. Each marten set usually consisted of several trap arrangements as described above. Several scent trails were laid down by dragging a piece of burlap soaked with sucker oil across the snow to each runway log.

|

| Fig. 87. Typical Lawrence marten set with runway log and staple attachment for scented bait. (Kenneth Diem Coll., Laramie, WY.) |

Coyote trapping was similar with several variations. Usually a bone soaked in sucker oil was wired to a tree as shown in Fig. 88. Traps covered with litter and/or snow were then placed around the base of the tree and one in a path leading to it. The coyote was captured while it was trying to reach the bait. In addition, traps were buried in runways used by the coyotes. Mink, weasels, red fox and lynx were also captured by these methods. Coyotes were also shot over bait. The method used most often involved placement of pieces of horse or coyote carcass under brush and logs usually on the open space of the ice of Jackson Lake. The coyotes were shot while attempting to dig down to the carcass.

|

| Fig. 88. Typical Lawrence coyote scented bone set. (Kenneth Diem Coll., Laramie, WY.) |

Coyote pelts were removed at the trap site and pelts of all other animals were removed at the ranch in the form of a tube or "case" skinned. If pitch from the tree got on the pelt, Verba used butter or lard and a fine tooth comb to remove it. The fleas on the marten were a problem, so the marten were brought home in a plastic bag. Since Verba was allergic to the flea bites, it was fortunate the fleas did not stay in the house.

Complete accurate records of the Lawrences' fur catches were not available. However, Verba's diaries provide data that represent at least the minimum number of animals and the proportions of each species taken. For the years 1931 through 1950, a period of the most active trapping by the Lawrences, she reported they trapped or shot the following (V. Lawrence, 1931-35; 1936-40; 1941-45; 1946-50):

101 coyotes

63 weasels

1 lynx

8 mink217 pine marten

5 red fox

1 skunk

Slim said their catch averaged $1,000 to $1,500 per year from the sale of their pelts to Lipshawn, a fur buyer in Idaho Falls, Idaho (Fig. 89). Their best marten fur price was $70 for a prime pelt right after World War II (W. Lawrence, 1981).

|

| Fig. 89. Slim with half a season's fur catch. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

The Lawrences received some trapping assistance from a large tomcat they inherited from the Grimmeseys when Slim and Verba moved into the Mae-Lou-Lodge. The cat lived a hazardous life outside the buildings since the coyotes were constantly running him up a tree. However, he caught a lot of weasels and brought them back to the lodge for Slim. One winter, the cat accounted for 20 of Slim's weasel pelts (W. Lawrence, 1981).

During the 1940s and later, Verba was doing much of the trapping. On December 11, 1944, she wrote (V. Lawrence, 1941-45), "Can't trap everyday — Two weeks wash." Reflecting back on all of their trapping, Slim commented (Teton Magazine, 1977),

"Funny thing I used to trap coyotes to beat hell; marten, too. Had to make a livin' by trappin' marten. I wouldn't touch one now. I just wouldn't. Wouldn't think of hurtin' one of them. It's funny how you change. Of course that was the goin' thing then. Everybody trapped. They had to get a little extra money. Ranchers didn't have much money in the early days."

Being proficient with firearms was an absolute necessity when your next meal or your life might depend on it. Both Slim and Verba were excellent marksmen which was attested to not only by the game they killed but by their numerous prizes at local shooting contests. Slim's preferred gun was his 30-06 rifle. Verba used two rifles but used her 270-caliber most often. She was a particularly good shot with a 22-caliber pistol.

The local contests involved turkey, prize money, ham, chicken and grocery shoots. Contestants paid an entry fee which helped finance the prizes. In 13 contests during the months of November, December and January between 1951-54, Slim won 7 turkeys, 8 money prizes, 9 hams, 5 chickens and 2 boxes of groceries. In one shoot on December 14, 1952, Slim won 3 hams and 4 chickens. Unfortunately, women's equality had not yet been heard of; and for most of the shooting contests, Verba was not allowed to participate (V. Lawrence, 1951-55).

Hunting was more of a necessary activity for Jackson Hole residents than a means of recreation. Slim recalled "Everybody lived on elk. You had to.... My wife and I would each have an elk. We just hung it up and let it freeze and thaw all winter. It got awful tough by spring" (Jackson Hole Guide, 1971).

Like her trapping, Verba's hunting skills were not developed until after her marriage to Slim. The majority of their elk were killed east of Arizona Lake. They used saddle horses for most of their hunting. As mentioned before, Slim had suffered a series of serious injuries to his back. The cumulative effect of these injuries made it impossible for Slim to ride a horse or walk any long distances after 1947. Nevertheless, Slim stayed active with the use of his four-wheel drive vehicles by clearing several jeep trails to a few of his favorite hunting areas (V. Lawrence, 1931-35; 1936-40; 1941-45; 1946-50).

After 1947, Verba was the primary hunter-trapper of the family. She was not a large woman, but was apparently well-coordinated, strong, durable and self-confident. On October 29, 1952, Verba reported, "Took off for Pilgrim Butte about 1:00—left Boone at the lake—took a short walk to the south, got a cow elk—surely surprised me, Packed half in." She also killed several moose when hunting alone but required Slim's help to dress and haul the animals home (Fig. 90) (V. Lawrence, 1941-45; 1951-55).

|

| Fig. 90. Verba leading a pack horse carrying a moose she killed. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

The Arizona Creek, Arizona Lake and Pilgrim Creek area seemed to have an inordinate number of black and grizzly bears. Slim felt Yellowstone Park rangers were regularly dumping some of their problem bears in that area (W. Lawrence, 1979). Some credence for that was the observation of seven grizzly bears on May 24, 1943, five of which were yearlings and two were cubs unaccompanied by adults (V. Lawrence, 1941-45).

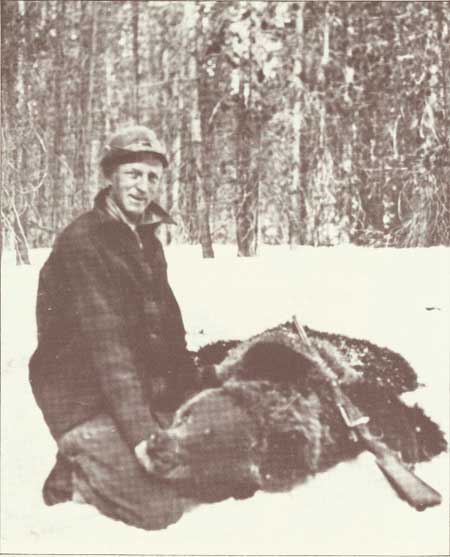

All too frequently, bear hunting turned out to be a matter of animal control at the ranch. Their dogs and particularly Cap, the Lewellyn setter-collie cross, were good deterrences to keep the bears out of the ranch. During the construction of the Berol Lodge, the workers maintained a cookhouse and meathouse on the property. Slim recalled that 30-35 bears were continually breaking into those structures which necessitated the killing of some of those animals (Fig. 91). Bears continued to damage ranch property. A number of these incidents occurred at night. The dog, Cap, probably saved Slim's life when three grizzly bears created such a turmoil early in the morning of May 14, 1934, that Slim had to intervene. He shot and wounded one bear and the other two bears ran off. The wounded bear charged Slim who had only one escape route and that was the chicken house. Cap harried the wounded bear long enough to allow Slim to climb onto the roof. The next morning the wounded bear was found dead several hundred yards from the ranch (V. Lawrence, 1931-35; W. Lawrence, 1981). When Cap died years later, Verba commented, "Old Cap our most faithful friend is gone. I hope they will let him chase bear in dog heaven. No human was ever as loyal as old Cap" (V. Lawrence, 1941-45).

|

| Fig. 91. Slim with grizzly bear he shot near Sargent's Bay. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Slim searched for bear dens during the winter hibernation period because the best pelts for fur rugs were on hibernating bears. Spring bear hunting over bait was another means to acquire a good quality skin. Also, the Lawrences maintained two bear bait cribs near Arizona Lake where they, Johnson and Berol would shoot bears in the spring (Fig. 92) (W. Lawrence, 1981).

|

| Fig. 92. Lawrences' bear bait crib: (A) vertical log wall enclosure and (B) horizontal log decking within log walls which covered the decaying bait. (Kenneth Diem Coll., Laramie, WY.) |

Verba enjoyed the excitement of hunting bears. In the blind near one of the cribs, Verba had constructed a comfortable seat of old bedding; and while waiting for bears to come, she would mend socks (V. Lawrence, 1936-40). Verba commented about one of her horseback trips, "Went up to Lookout, on my way home I found the biggest grizzly at the bait. Too frightened to shoot. He was gone when C and I went back."

In addition to the waterfowl hunting described earlier with Johnson and Berol, Verba and Slim hunted ducks at the various ponds between the ranch and Moran. Ruffed and Blue Grouse were taken regularly by Verba with her 22 pistol as she rode horseback in the fall. She and Slim went after their antelope in a variety of places including the Pitchfork Ranch west of Meteetsee, along the Green River, the Big Sandy area and around the Sweetwater River Crossing (V. Lawrence, 1931-35; 1936-40; 1941-45; 1946-50).

Besides his bighorn sheep and mountain goat hunting with Johnson, Slim hunted bighorn sheep at the head of Red Creek in the Gros Ventre Range and the Hidden Basin area northwest of Dubois. On one October hunt to Hidden Basin, Slim recalled a terrible snow storm. They had to drive the horses out ahead of them to make a trail to leave camp. When they left, Slim did manage to carry out a sheep head, even though they had to leave their gear in the Basin until spring (W. Lawrence, 1979; 1981).

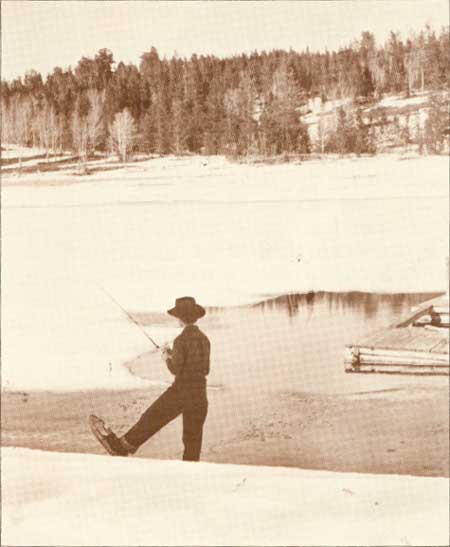

While Slim enjoyed occasional fishing, Verba was a fishing fiend (Fig. 93). She had not fished prior to her marrying Slim. Her first catch was so exciting, she used her new rod as a club to disable the fish, breaking the rod (W. Lawrence, 1981). From that time on she was addicted. Even in 1942, after she broke her leg skiing behind the motor toboggan (W. Lawrence, 1979), she went ice fishing with a cast on her leg (Fig. 94). Besides Jackson Lake, they fished in a number of ponds and lakes. Slim had helped build and stock many of these in the late 1920s and early 1930s with brook trout obtained from the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission hatchery at Daniel (V. Lawrence, 1931-35; W. Lawrence, 1981).

|

| Fig. 93. Verba on snowshoes fishing Sargent's Bay in spring. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 94. Verba fishing from motorized toboggan after breaking her leg. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Of all of the Lawrences' outdoor activities, they probably pursued hunting for Indian artifacts with the greatest fervor, especially around Jackson Lake. These were usually early morning excursions looking for surface finds. In later years, some of the collecting extended to exploration trips to the desert Southwest in their trailer and camper truck. The results of some of their efforts in Jackson Hole have been well-documented (G. Wright, 1975-76; Rudd, 1983).

"Tuskers" were part of the history of northern Jackson Hole, particularly around 1905. These men illegally killed bull elk just to extract the animal's two ivory teeth. Charles Purdy, a notorious tusker, told the Lawrences years later about six old cabins used by these men and the general locations (Casper Morning Star, 1960). Again, the Lawrences' curiosity got the best of them. Consequently, they sought out these tusker structures and gathered valuable information about their function and use. As Verba recounted,

"In so doing, it has taken us all over Jackson Hole, both on horse and by foot ... every trip has been a never-tiring scenic thrill, adding to it the possibility that we might find something..." (V. Lawrence, 1954).

One of the early tusker cabins was located in the middle of the area where Slim and Verba hunted and trapped. It was so well hidden, it took four trips to relocate it after Slim first discovered it (W. Lawrence, 1981).

By the time Slim had spent over 20 years on the Johnson-Berol ranch, his insatiable appetite for the collecting of historical artifacts, memorabilia and photographs was fast outstripping his ability to store those items, which ranged in size from Indian trade beads to old ox yokes and wagon parts (Fig. 95). Verba urged Slim to reach a decision to do something with the collection besides storing it in their house and on the property. The problem was solved on June 5, 1958, when he and Homer Richards established the Jackson Hole Museum to house and display the many historical items Slim had collected. They used a building in the town of Jackson owned by Homer. Over the next 12 years, organizing and operating this museum from Moran consumed much of Slim's and even Verba's free time (W. Lawrence, 1979; Jackson Hole Guide, 1977; Jackson Hole Museum, 1958).

|

| Fig. 95. Slim in his living room with a small part of his artifact, memorabilia and gun collection. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

When reading Verba's diaries, particularly prior to 1947, one is struck by the relatively few days they spent confined indoors because of adverse weather. During these periods, Slim and Verba invariably worked with the collection of various artifacts, memorabilia and historical photographs. In addition, Slim had a fine tool shop and ammunition reloading facility in which he spent many hours. Verba occupied herself with braiding rag rugs, sewing and putting together jigsaw puzzles. Also, she and Slim would play a lot of cribbage. Verba tried with little success to interest Slim in chess (V. Lawrence, 1931-35).

During those years when the road to Moran was blocked with snow, park rangers wintering at the South Entrance of Yellowstone National Park stopped at the Lawrences for a halfway rest stop on their way to Moran for supplies and mail. Two of these rangers, John Jay and Lee Colman, shared a common interest in guns and dogs with Slim. It was John Jay who brought the dog, Cap, to Slim and Verba. Slim and Lee Colman talked and traded guns for hours. On one visit in 1932, Verba (V. Lawrence, 1931-35) observed, "Lee and Cecil talked guns even more than usual, on second thot could it be possible." Many of the evenings with the rangers were spent playing bridge. With the advent of the snow plane in the 1950s, these visits by the park rangers diminished.

Verba liked to ski for pleasure and had Slim clear a run at the AMK, from the ridge down to Jackson Lake. In addition, Verba would harness one of the sled dogs to pull her as she skied. In later years, she skied on Togwotee Pass and in Jackson. Slim's back injuries eliminated that activity for him in the 1940s.

While they did a lot of walking in their earlier years on the ranch, one of the hikes they looked forward to each year was at Easter. They kept a special trail cleared of fallen trees from the ranch along the west edge of the timber above the Lake to the northern end of Sargent's Point where the snow melted early. Another ritual they followed was to take flowers to the graves of Sargent and Johnson on Memorial Days.

Besides their entertainment value, community social affairs were particularly important winter events which served to mitigate the adverse impacts of isolation, as well as providing an opportunity to visit with distant friends and neighbors. In winter, travel to these social affairs could be slow and difficult (Fig. 96). Consequently, prior to the 1950s, parties and dances were all night affairs with participants getting home the next day (Fig. 97). Verba and Slim attended many of these parties and dances at the Moran schoolhouse, Toppings ranch at Elk, and along the Buffalo Fork at Turner's ranch, Hatchet ranch, Gregory's ranch and Neal's dance hall (Fig. 98). Many of the affairs were ski parties followed by a dance. Later, a number of these events were held in Jackson in connection with the Elks, Old Timer's Party, Wort Hotel and the Cowboy Bar.

|

| Fig. 96. Bobsled transportation to dance at the Hatchet Ranch leaving from Gregory ranch. Slim and Noble Gregory on skis in front. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 97. The Wolff band: Willie, Stippie and Bessie. Ben Sheffield's lodge, Moran, WY. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

|

| Fig. 98. Easter party at Turpin Meadow Ranch: Back row, John S. "Dad" Turner, Jim Simon, Verna Allen, Betty Feuz, Marion Turner Scott, Dorothy Simon, Eunice Braman; Front row, Florence Lozier, Kay Davis, Verba Lawrence, Maytie "Ma" Turner, Esther Allan. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Slim and Verba had broad interests that extended beyond Jackson Hole and Wyoming. From the late 1930s on, they were able to travel either in the late fall or early spring. In 1949, they bought a trailer for these trips and then an Alaskan camper for their pickup in the 1960s. Their curiosity took them to all of the western states with more frequent trips to the Southwest. They also made short trips by plane and car to see special events like the Western Stock Show in Denver. Other trips were made around Wyoming to attend gun and gem shows or to search for rocks and old, purple bottles, etc.

In 1953, Verba learned of the opening of the Moran postmaster's position. Slim stated she was curious about the job responsibilities and decided she'd further her education by studying the examination materials. When the exam was given, Verba took it and had the highest score; and after Congressional approval, she started as Moran's new postmistress on July 26, 1954 (Fig. 99) (Wyoming State Archives, 1954). This new responsibility, along with Slim's work in the Jackson Hole Museum, changed their life-style considerably. Both Slim and Verba found the freedom and flexibility of the early years being eroded away. Even so, Verba adjusted and still got out to ride horseback and ski. She held this post until her retirement on June 12, 1967 (V. Lawrence, 1967-68).

|

| Fig. 99. Verba outside old Moran post office. (W. C. Lawrence Coll., Moran, WY (Jackson Hole Museum).) |

Like his uncles and father, Slim succumbed to the adventure of mining hidden wealth. In the early 1930s, Slim and three partners, Charlie Fesler, Don Graham and James Webb, located and worked an asbestos-talc mine in Owl Creek at the northern end of the Teton Range. They had built a blacksmith shop, a tool shed and a lean-to on this mining claim, situated on the south facing slope of Owl Creek just above the confluence of Owl and Berry Creek. This site is not to be confused with another company's asbestos mining venture in Berry Creek. The talc deposit was likely the source of the many soapstone Indian artifacts that Slim and Verba were finding. In addition, Slim filed a gold claim at Colter Bay. Nothing came of any of these ventures (W. Lawrence, 1979; 1981; Jackson s Hole Courier, 1935).

Like so many things Slim did, he could not be so close to such a rugged mountain range like the Tetons without trying to do some mountain climbing. Even though his climbing experience was short-lived, he did participate in two first-time climbs. On August 30, 1932, Phil Smith, Walcott Watson and Slim completed the first climb of Eagles Rest Peak just north of Mount Moran (Fryxell, 1978; Watson, No date). Verba's anxiety and concern about the appropriateness of Slim's climbing were reflected in her diary when she wrote (V. Lawrence, 1931-35), "They reached here at 7:30 this morning. I was never so relieved in my life, Cecil's Mt. climbing days are over." The next day Verba remarked, "Poor Cecil, his feet and hand are swollen yet. I'm certain he'll be content on low ground, from now on." Verba's predictions did not come true for Slim was persuaded to attempt the first successful moonlight climb of the Grand Teton with Len Exum's group on September 9-10, 1933 (W. Lawrence, 1979).

Sometime in the 1940s, Slim helped originate the "Jackson Lake Ice Breakup" contest to give residents of Moran a new interest in the winter and spring. A 50-gallon metal barrel was placed on the ice west of Moran. Jackson Hole residents then made their prediction of the exact time when the barrel would touch the shore which was then the official time of the ice breakup (W. Lawrence, 1979; W. Lawrence, No date).

Despite all of their other activities, Slim and Verba found time to belong to a number of organizations. To name a few, Slim was particularly active as a 32nd degree Mason and as a Shrinner member of the Sheridan Kalif Temple and a lifetime honorary member of the Rawlins Korein Temple. Verba was a member of the Eastern Star and American Legion Auxiliary. She also served as Secretary and Treasurer of the Wyoming Section of the National Association of Postmasters of the U.S. Both Slim and Verba were active in the Elks (BPOE). In 1935, Slim was a charter member and on the Board of Directors of the Jackson Chapter of the Izaak Walton League of America. In the early 1940s, Slim served two terms as a member of the Wyoming State Historical Advisory Board. Continuing his historical interests, he became a charter member of the Wyoming State Historical Society. Also, he was a charter member of the Westerners first Wyoming Chapter (Laramie) where he had been a contributor to their Brand Book and had been elected "Top Hand" in one of them (W. Lawrence, 1979; 1980; No date; V. Lawrence, 1961-65; Jackson Hole News, 1970; Jackson's Hole Courier, 1935a).

Besides Slim's Jackson Hole Museum collections, his other contributions were especially significant. The selection of his design for the Union Pass Commemorative Medallion was important, as well as his work to establish recognition of the Trapper's Trail along the east shore of Jackson Lake. It was he who located and arranged for the transportation of the granite stone marker that was placed on the trail near Leek's Lodge (Jackson Hole Guide, 1966; 1973).

Several organizations have made special efforts to recognize Slim for his many and varied contributions. Slim and Homer Richards were honored in 1958, by the Wyoming State Historical Society, which presented them with their Historical Award for establishing and maintaining a fine private museum and for preserving Wyoming history (W. Lawrence, No date). On May 16, 1974, the Teton County Historical Society honored them for "having had the foresight to save some of the more important things of Jackson Hole" (Jackson Hole Guide, 1974a). In 1975, the Jackson Hole Outfitters and Guide Association presented Slim with an honorary lifetime membership (W. Lawrence, 1981).

When Verba retired as postmistress in 1967, she and Slim were looking forward to building a house of their own. In an agreement with Alfred Berol, they were to build the house on the AMK Ranch. Slim and Verba worked hard clearing out trees and brush at their homesite in the Spring 1968. Work began on construction of the house on July 10, 1968, and was completed that fall. Unfortunately, Verba suffered a stroke during that period. Even though she was able to return to the ranch and their new home, her physical condition was progressively deteriorating. On July 8, 1970, Verba died of a self-inflicted bullet wound (Jackson Hole News, 1970). She was buried at the Lawrence gravesite immediately adjacent to the Johnson memorial and near Sargent's grave.

Slim remained active and lived alone in his new house on the ranch until 1983. At that time, he moved to a nursing home.

Seventy-one years had elapsed since Slim met John D. Sargent and first saw the ranch. Together, Slim and Verba had spent 40 continuous years working for Johnson and Berol on that same property. Their contributions in those many years to the ranch and to its owners were significant. With the passing of the Lawrence era, hopefully the present owners, the National Park Service, will continue the historic dedication and support necessary to preserve the unique Marymere/Pinetree/Mae-Lou/AMK Ranch.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

dough_gods/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 17-Jun-2011