|

Hopewell Culture

Amidst Ancient Monuments The Administrative History of Mound City Group National Monument / Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio |

|

CHAPTER TEN

The Long Road to Hopeton

From the onset of National Park Service involvement at Mound City Group National Monument, managers and cultural experts lamented that the site under their care represented a macabre aspect of Hopewell culture, its peculiar graveyard and funerary aspects. "The City of the Dead" itself was surrounded in Ross County by other Hopewell-related earthworks containing clues that might shed more light upon this mysterious civilization, the greatest prehistoric culture of eastern North America. While a surprising number of these sites had survived centuries of Euro-American occupation, efforts to preserve them had largely been as a result of enlightened and sympathetic private landowners. As time passed and economic conditions changed, however, such private sector benevolence could not guarantee the preservation of remaining Hopewell sites in perpetuity. The public sector slowly came to this realization in the late twentieth century.

|

|

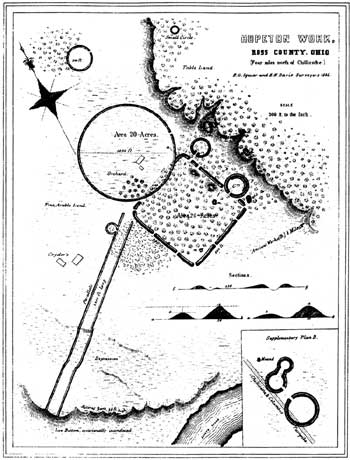

Figure 77: Squier and Davis' drawing of Hopeton

Earthworks. ("Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi

Valley"/1848) (click on image for larger size) |

Clearly, if the National Park Service took its preservation mandate seriously, the Mound City Group could not be the sole Hopewellian site within the national park system. As serious planning efforts for Mound City Group began in the 1950s, this concept received much discussion, especially once MISSION 66 development for the Chillicothe monument became agency policy, forever renouncing notions of allowing Mound City Group to revert to state management and operation. From the late 1950s onward, the National Park Service committed itself to playing a key leadership role in understanding, educating, and preserving significant sites related to the Hopewell culture. The impetus for this preservation vision lay just across the Scioto River from Mound City Group National Monument at the Hopeton Earthworks.

Significance of the Hopeton Earthworks

E. G. Squier and E. H. Davis first described "Hopeton Works" in 1846, stating the earthworks consisted of "a rectangle, with an attached circle, the latter extending into the former, instead of being connected with it in the usual manner. The rectangle measures nine hundred and fifty by nine hundred feet in diameter." Continuing the description, they wrote: "The walls of the rectangular work are... twelve feet high by fifty feet base, and are destitute of a ditch on either side. The wall of the great circle was never as high as that of the rectangle; yet, although it has been much reduced of late by the plough, it is still about five feet in average height." [1] The accompanying lithograph depicts the site, spelled slightly different than the nearby settlement of Hopetown about four miles north of Chillicothe, sitting beneath the table land on "fine, arable land." Four small mounds and three small attached circular enclosures are depicted. Where the twenty-acre circle and equally large square conjoin, two, 2,400-foot-long parallel earthwalls proceed across the farmland toward the river, slicing through a natural depression, to an area marked "low bottom, occasionally inundated." The manmade feature, perhaps intended as a promenade, points to the south of Mound City Group on the opposite bank of the Scioto. [2]

While Superintendent Clyde King spoke often of the Hopeton Earthworks to anyone who would listen, his belief in the site's significance and its inherent interrelation with the national monument received validation when the Washington Office instructed Northeast Region officials on October 3, 1958, to assist in preparing site surveys for potential national historic landmarks (NHL). NHLs were recommended by the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments for designation by the secretary of the interior. Known as the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings, the NHL program was authorized by the Historic Sites Act of 1935. Once contextual themes were developed following World War II, concerted initial nationwide surveys began in the 1950s and concluded in the early 1960s. While outstanding sites could receive NHL status and remain in private ownership, others found to possess exceptional value to the nation's history were eligible for inclusion in the national park system.

Regional Archeologist John L. Cotter got the nod to prepare the "Hopeton Group" site survey. Philadelphia officials were eager "to formulate a definite opinion as to the nature and value" of the site, but believed from the start that Ohio should manage it and would "encourage them to obtain title to it." [3] Cotter finished his survey and sent it to Washington in early 1959, when Regional Director Tobin informed Director Wirth that "It is our feeling that Hopeton Group is a portion of an archeological unit represented by Hopeton Group, Mound City Group, and the large adjacent circular earthwork now on the land of the Department of Justice which should be considered as closely related to the rectangular necropolis of Mound City Group. Therefore, full consideration should be given to the interpretation of all of these earthworks together." [4]

Relating the results to Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society Director Erwin Zepp, Tobin stated, "We believe that at present too little is known of the actual cultural definition of this site to link it positively with Mound City Group. Nevertheless, in our opinion, the Hopeton Group represents one of the few presumably Hopewellian earthworks which still has a trace of circular and rectangular earthworks in conjunction, together with an associated causeway of parallel earth walls and earth mounds." He nominated the state society as the best agency to preserve the site, and should further study establish a definite association with Mound City Group, Tobin pledged to integrate interpretive programs at both sites. [5]

Philadelphia officials placed too much credence in Erwin Zepp's statements that the Hopeton Earthworks would be favorably considered for acquisition by the Ohio legislature. This belief pervaded state-federal discussions in the late 1950s and perhaps influenced a 1958-59 boundary study by Andrew Feil of the Northeast Region's National Parks Planning division to recommend against administratively declaring Hopeton to be within Mound City Group National Monument's boundaries. In the fall of 1960, National Park Service officials were stunned to learn that Zepp had not included Hopeton on the 1960 list of to-be-acquired sites, nor had he done so in previous years. In response, dramatically shifting its position, the Philadelphia office recommended Hopeton as one of two sites in the Northeast Region to be considered as potential national monuments. [6]

Zepp's duplicity prompted Regional Archeologist John Cotter to press ahead and make the case for Hopeton's national significance. In the total absence of state action, Cotter declared "the Hopeton site can only be preserved through the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings recommendations." [7] Cotter felt the two sites were strongly linked, and NPS management of an enlarged national monument was "logical and warranted for the complete interpretation of the story." Further, he concluded, "The statement of purpose and justification in the enabling legislation of Mound City Group can as well apply to Hopeton." [8]

In February 1961, Regional Director Ronald F. Lee brought events at Hopeton to Director Conrad Wirth's attention. The previous month, Lee agreed to consider amending Mound City Group's boundary survey report to include Hopeton. He reported news from Clyde King concerning a threat of residential subdivision within the earthworks itself. A sixty-eight-acre section called the McKell tract was subdivided by owner/developer Merrill Vaughn of Chillicothe and his agent, Donald H. Watt of Columbus. The immediate threat was one side of the twenty-acre square had one of its earthwalls leveled by a bulldozer. To help orchestrate public pressure to halt the destruction, the National Park Service notified Robert Garvey, National Trust for Historic Preservation director. [9]

While no additional ground disturbance occurred, the development action by a landowner unimpressed by prehistoric values prompted King to prepare information about the site to send to Columbus and Philadelphia in March 1961. [10] In the fall of 1962, a meeting with Ohio Historical Society's Curator of Archeology Raymond S. Baby and Mound City Group Superintendent John C. W. Riddle and Archeologist Richard Faust took place in Columbus primarily to discuss contractual relations the following year for an Accelerated Public Works program. The men spent considerable time discussing Hopeton Earthworks and its need for preservation. The meeting laid the groundwork for a new spirit of cooperation between the two agencies, and Baby pledged to keep an eye on Hopeton for the state. A change in the society's site management leadership promised new hope for state acquisition efforts. [11]

Renewed NPS confidence in Ohio's acquisition of Hopeton lead to incorporating into the 1963 Mound City Group interpretive prospectus the assertion that "The State of Ohio plans legislation to acquire and develop Hopeton." [12] But even before the document's ink was dry, NPS officials knew state action would not be forthcoming. On March 12, 1963, Cotter learned from Raymond Baby that severe state budget cuts not only resulted in closing all state memorial parks, but ended plans for Hopeton until fiscal matters improved. Faced by this news, John C. W. Riddle continued to support NPS acquisition by revising Mound City Group's boundary. Cotter concurred, calling it "the only possibility of saving this site." [13]

Monument staff researched county deeds to determine Hopeton land ownership and prepared plat maps on each interest for Riddle's meeting in April 1964 with regional officials. Riddle reported an "interesting discussion" took place, and mused about "the possibilities, someday, of a direct tie in with Mound City." [14] Riddle's lack of enthusiasm was probably related to the 1964 "Parks for America" publication, the last such NPS report anticipated for nationwide park planning before that function officially transferred within the Interior department to newly-created Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. In its treatment of Ohio, "Parks for America" noted "sites illustrating the prehistoric cultures that once flourished in Ohio have great educational value." Unfortunately for Hopeton Earthworks and other meritorious archeological sites, the agency's recommendation called for adding no prehistoric sites to the national park system. [15]

In July 1964, a public announcement from Interior Secretary Stewart L. Udall's office included Hopeton Earthworks on a list of four Ohio national historic landmarks. Completing work by the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings of archeological properties, Hopeton Earthworks joined Newark, Serpent Mound, and Fort Ancient National Historic Landmarks thus elevating these sites for preservation in the public mindset. [16]

Four years passed before any substantive state action transpired regarding Hopeton Earthworks NHL. On December 13, 1968, the Board of Advisors of the Ohio Historical Society considered a proposal by Raymond S. Baby to acquire 250 acres at Hopeton. While the board viewed Baby's pitch favorably, it viewed owners Vaughn and Barnhart as unwilling sellers by asking an inflated selling price. The board threw its support to acquiring Seip Mound as its first priority, but instructed the society's director to try acquiring Hopeton by "other means," including options to buy. Spurred by developments in Columbus, Superintendent George Schesventer advocated proceeding with more Hopewell-related research, concluding "Hopeton and Mound City may be miles apart in the bureaucratic sense, but they are almost as one in the story of the Hopewell Culture of the Scioto Valley." It was up to the Park Service, Schesventer believed, to make the case crystal clear. [17]

Park Expansion and Local Reaction

The ambitious park expansion effort launched by Superintendent William C. Birdsell in the early 1970s had Hopeton Earthworks as the only tract nominated for acquisition not already federally owned. While Birdsell worked to secure state and local support for Hopeton's addition, he also used his political savvy to court congressional representatives and expressed optimism about having the national historic landmark included in the final legislative package. Gone were the days when the agency could merely administratively determine adjustments in park boundaries. During the 1960s and 1970s, Congress had clearly asserted its authority over the executive branch in such matters. [18]

Bill Birdsell failed to see progress made on Hopeton Earthworks during his tenure other than the preparation of a formal National Register nomination, the primary purpose of which was to establish a firm boundary. Upon passage of the National Historic Preservation Act on October 15, 1966 and creation of the National Register of Historic Places, cultural units of the national park system like Mound City Group and all NHLs, including Hopeton Earthworks, were automatically added to the national inventory of significant properties. Because Hopeton Earthworks NHL preceded the 1966 act, it lacked the required nomination form and an official boundary determination. When Fran Weiss, Washington Office archeologist, accompanied by Martha Otto of the Ohio Historical Society, arrived in August 1974 to walk the NHL and decide on a boundary, they stood on the Barnhart tract and peered over the fence at the Vaughn tract. The latter landowner flatly denied permission to access his property. Nonetheless, the National Register nomination form went forward on November 8, 1974. [19]

Archeological testing at Hopeton Earthworks to determine its significance and integrity took place in the summer of 1976 by David S. Brose, curator of archeology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and instructor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Brose's September 1976 report represented the first phase of a suitability/feasibility study undertaken by the Midwest Regional Office. Brose determined the site's national significance and integrity made it a worthy addition to the national park system. [20]

The second phase to determine feasibility began in January 1977 with formation of the planning team. Primary members were team captain Allen Hagood and Park Planner Donald Clark, both of the Denver Service Center, and Superintendent Fred Fagergren. Technical experts were F. A. Calabrese, manager of Midwest Archeological Center, and Finis Rayburn, land appraiser at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, Indiana. Delays in Denver postponed team information-gathering and public meetings until late July 1977, and other service center projects intervened to push progress on Hopeton until later the following year. [21]

The delay proved costly. In October 1977, the Chillicothe Planning Commission approved a development plan for a one hundred-fifty-unit apartment complex south of Barnhart Road, adjacent to Ohio Highway 159 or North Bridge Street. Named "North River Place," the apartment complex, financed in part through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), was set for construction in spring 1978. Fagergren immediately informed both city and county planning commissions of the potential park development conflict, and found no zoning in effect to halt adverse developments, the city commission had merely ruled there were no housing code violations. Because planning was still underway and the agency's position remained "speculative and uncertain" without congressional action, Omaha regional experts determined NPS had no grounds to halt the development. [22]

|

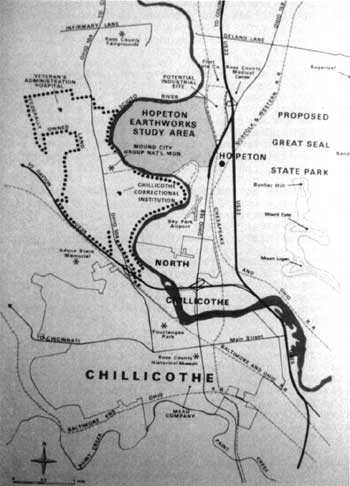

| Figure 78: Map of the Hopeton study area from the 1978 feasibility report in relation to other Chillicothe sites. (NPS/1978) |

Bordering on "apologetic," this unfortunate attitude permeated the agency's regional and Washington-level decision-making, which resulted in reactive, not proactive, resource preservation. On matters archeological, NPS lacked political will or astuteness. Indeed, the Park Service failed to include its own Midwest Archeological Center as a full partner in the discussion concerning Hopeton and other Hopewellian sites. Testifying before Congress, NPS officials could not answer basic questions concerning the endangered resources, reflecting its ingrained bias and second-class treatment of all things archeological. At the regional level, communication became funneled through the Midwest Regional Office's public affairs officer, Bill Dean, who strangely enough also served as liaison to Washington Office legislative specialists. Dean placed tight restrictions on information exchanges, and at one point forbade professional interaction with the Archaeological Conservancy, a group he perceived as unwelcome interlopers, and not valued preservation partners. To his credit, Regional Archeologist Mark J. Lynott ignored Dean's order. Lynott later recalled,

The Park Service's whole involvement in Hopeton was one of an apology. All the problems that we have out there today we have only ourselves to blame because we have never taken an assertive stance on preservation of that resource. It's a chronic problem that this organization has. I mean, in my opinion, we like to wave the flag that we're this great preservation agency; but the fact of the matter is, there is absolutely no courage on the part of any of our leadership to preserve something that's worthwhile.... It's been a view from management at the top: Washington and some of the former upper level managers at the Midwest Region. The commitment just has not been there to take the stance to preserve the resources in Ross County that should be preserved. [23]

In the interim as planning efforts plodded ahead, the first academic conference ever held in Chillicothe concerning the Hopewell culture took place for four days in March 1978. Co-sponsored by Mound City Group National Monument, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and the Mid-Continental Journal of Archeology, the gathering represented the first such conference since 1961 and produced a valuable synthesis on Hopewell archeology. More than forty professional papers were presented at the well-attended "Conference on Hopewellian Archeology." The NPS arranged an afternoon tour of area Hopewell sites, with much discussion concerning Hopeton Earthworks and the need to preserve such sites. [24]

By late May 1978, Regional Director Beal approved final changes to "An Evaluation of the Feasibility of Adding Hopeton Earthworks to Mound City Group National Monument." It boldly stated that "Hopeton Earthworks and Mound City Group should be protected as a combined resource, administrated [sic] as a single unit of the National Park System. Should the combination of alternatives we recommend be approved and enacted, approximately 1,020 acres would be added to the System--477 acres in fee and 543 acres with a combined scenic and archeological easement." [25] Fagergren seized the opportunity to press for consideration of a name change for the expanded park, but offered no suggestion. He also heralded the idea of establishing an archeological center similar to the Chaco Archeological Center to study the Eastern Woodland Indians. Finally, he urged expedited drafting of legislation for Interior department approval so that citizens could hear the federal government's position as soon as possible. [26]

Fagergren's concern over public reaction proved well-founded as rumors about federal land acquisition plans swept Ross County. Even before official study results were known, special interest groups such as the Ross County Taxpayers Association, Ross County Farm Bureau, and East Side Civic Improvement Association passed resolutions opposing park expansion to include Hopeton and other prime industrial, commercial land. An informal group representing these opponents from the business community appeared before the Ross County Planning Commission in late June 1978 to urge that body to pass a similar resolution. Group leader, Larry Hardin, president of Hardin Real Estate and an investor in the stalled North River Place development, warned that the buffer surrounding the forty-acre Hopeton circle and square would be a thousand acres, putting a total of seven percent of Ross County in federal ownership. Hardin subsequently launched a petition drive objecting to the land being removed from tax rolls. [27]

Rushing to stave-off an avalanche of public opposition, Fagergren released the sixty-six-page suitability-feasibility study for public review on July 7. Stressing that the government had taken no position and the final approval was up to Congress, the alternatives ranged from the status quo to full federal purchase of 1,020.39 acres. Briefing the Ross County Planning Commission on July 18, Fagergren noted Maston Samson, owner of forty-five acres, as the lone favorable landowner, and acknowledged the selfish interests of the growing opposition. He downplayed economic impacts to the county's tax base, citing 1977 figures crediting more than seven million dollars annually pumped into the county by heritage tourism. Adding Hopeton, Fagergren argued, would only increase tourism profits. [28]

Congress had already acted on adverse impacts to local tax districts affected by federal land acquisition by passing Public Law 94-565, providing payments in lieu of taxes. In an effort to influence Congressman William H. Harsha, thought to be sympathetic with his anti-Hopeton constituents, NPS calculated 1976 valuations of the 1,020 acres at $4,080. Thanks to Congress, Ross County would get the same amount for the first five years following federal acquisition plus an additional $765 annually. After five years, the annual payment would remain at $765. With increased tourism revenues, Ross County would experience no adverse economic impact by this tax base reduction. [29]

Harsha's supportive nature as cultivated by Bill Birdsell in the early 1970s all but turned to hostility, thanks to miscommunication between the Washington and Midwest Regional Offices. Irked when his June request for a copy of the suitability-feasibility report was denied in Washington because of that office's understanding that it would not be available until fall, Harsha was rebuffed again even as the report freely circulated in Chillicothe. In an indignant letter to Secretary Cecil B. Andrus, Harsha claimed "I believe the National Park Service deliberately misled me. This apparent effort on the part of the bureaucracy to deceive a member of Congress is outrageous." Explaining the blunder, Andrus said the study could not be considered complete until Interior's position had been determined sometime in the fall, and apologized for the inadvertent error. [30]

With Carter administration approval, Interior's nod to include Hopeton Earthworks in the national park system finally came in February 1979. Previous suggestions to accomplish it by executive proclamation under authority of the 1906 Antiquities Act granting the president power to declare a national monument were laid to rest in favor of congressional action. Although approved for submission under section 8 of the General Authorities Act for 1978 and 1979, Interior's delay had spawned additional slowness in drafting legislation and pushing it through laborious reviews throughout 1979 [31].

News of firm federal plans for Hopeton prompted the Ross County Planning Commission to request Congress not to permit land or easement purchases until planning and funding were available for park development. It requested further that the minimum land area be acquired and current tax values be used for compensation. [32]

Commissioners made their statement based upon the knowledge that land values continued to climb. In December 1978, the commission gave final approval to developers HRH Properties, Ltd., for the 120-unit, $3.7 million North River Place apartment complex. Word of grant approval confounded NPS officials. The Washington Office informed Ohio HUD officials that funding for North River Place constituted a "direct conflict with adding Hopeton Earthworks to the National Park System." Receiving no response from HUD, Fagergren later learned that HUD claimed to have received none of the previous NPS protest letters on the subject, and lacking any written objections, HUD decided to proceed with the loan application. [33]

HUD did delay the project during 1978, requiring HRH to secure an archeological survey and then to supply the negative results to the state historic preservation office (SHPO) and the Keeper of the National Register, both of whom concurred that the tract lacked cultural resources. Intentionally deciding not to consult with NPS officials over the project, HUD proceeded through the section 106 consultation process, in accordance with the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, receiving both SHPO and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation's concurrence with a "no adverse effect" determination. Once the section 106 process concluded, HUD was free to proceed. Fagergren first learned in June 1979 of these developments as well as HUD's resolve not to change its mind, but to continue granting HRH time extensions to secure bonding for the HUD grant. A furious Fagergren found HUD officials had not bothered to read the NPS Hopeton study, believing that land lacking in cultural resources should not be of interest to NPS. When Fagergren pointed out the tract was ideal for his agency's own development facilities for Hopeton, the explanation fell on deaf ears. [34]

In a desperate effort to get the HUD grant terminated, Fred Fagergren attempted to reopen the section 106 process by contending NPS was omitted from the consultation and that adverse visual and audible effects to the adjacent Hopeton Earthworks NHL were not considered. His request for Omaha officials to reopen the case with the Advisory Council did precipitate news that the Council had determined that the low-rise nature of the buildings would have a minimal impact on the NHL. There was no precedent for reopening a completed section 106 case, but the Council said it would consult its solicitor should NPS decide to press the issue. To Fagergren's dismay, Regional Director Jimmie L. Dunning decided against it. [35]

On August 30, 1979, North River Place developers closed with HUD on its loan and were set to begin construction. The letter that Fagergren coaxed the Washington Office to prepare two months before for the interior secretary's signature was too late. Signed by Acting Secretary Robert L. Herbst to Acting HUD Secretary Jay Janis on September 9, the letter sought to prevent the two departments from working at "cross-purposes." It warned North River Place would "occupy the only available entrance for 100,000 visitors to Hopeton" and exappropriate the site for an NPS administrative facility. It warned that Interior faced the "unpleasant possibility" of condemning the HUD project. [36]

Reporting on the North River Place groundbreaking ceremony in late September, a dejected Fred Fagergren refused to give up. Pressing Omaha officials do more, including pressing for condemnation, Fagergren asserted: "I am appalled that we were unable to deal with the bureaucracy and have some effect upon this project. I remain convinced that some effort should be made to work with the Advisory Council to have them at least place requirements upon the apartment developers to provide the screening, which will be necessary, on their acreage. The responsibility is with the Council to minimize impact on historic resources. The NPS should not bear the responsibility of screening for off-site projects which are Federally backed. To plant vegetation north of Barnhart Road as screening will be very difficult and extremely expensive." [37]

Determined to put the matter back into perspective, Dunning stated no legislation had yet been introduced, and condemnation was "both premature and presumptive." With no acquired interests, screening requirements had no basis. Two events, however, soon changed Dunning's negative position. First, fall 1979 draft legislation to add Hopeton was introduced, then got incorporated into an omnibus parks bill. Second, Fagergren reported in mid-November 1979 that land east of Hopeton was under consideration for an industrial park development by Ross County Community Improvement Corporation. Encouraged by progress made on North River Place, developers were salivating to improve agricultural land to the east. [38]

In a December 20, 1979, meeting at the HUD office in Columbus, Jimmie Dunning spoke bluntly. Concerned by HUD's failure to communicate honestly, he threatened the political reality of one government department condemning the project of another, an embarrassing prospect in an approaching presidential election year. Dunning presented three ways to reach common ground and avoid condemnation: realigning the apartment complex entrance from Highway 23, not Barnhart Road as designed; installing extensive vegetative screening; and to fence along the south edge of Barnhart Road to separate apartment dwellers from tourists. Should these modifications be made, NPS would then request that the development site be removed from the Hopeton acquisition. Dunning called for another meeting in early 1980 to discuss mitigation measures. Failure to satisfy NPS concerns, he warned, would bring certain litigation. [39]

Threats Escalate, but Congress is Slow to Act

The promised mitigation meeting had ominous results. The developer failed to attend, contending instead with a construction site strike, and HUD reneged on earlier assurances it could leverage the developer to make changes. Fred Fagergren's suspicions that the earlier meeting had merely allowed HUD to claim it listened to NPS concerns proved accurate. He later learned that an Advisory Council on Historic Preservation stipulation to HUD was for that agency to consult with NPS on the project. Until it did, and reported back to the Council, section 106 compliance had not been completed, and HUD illegally proceeded with project approval. Surprisingly, a meeting with developers did take place a week later and representatives were amenable to making design changes. [40]

A mid-February conference in Washington, D.C., on the apartment complex brought consensus that NPS could not afford to pursue condemnation with a tract price of $1.8 million and improvements at $3.5 million. NPS would instead work for maximum mitigation measures, and if those failed to materialize, language would then be inserted in the Hopeton legislation to provide funding for NPS to install mitigative features. The following day, Fagergren and Dunning met with Advisory Council officials to confirm that HUD failed to complete section 106 compliance and would be notified of their illegal action and urged to work closely with NPS on mitigation. Council staff members acknowledged that intense political pressure had been imposed on them to pass the apartment complex project through the section 106 process. [41]

Although no names were used, NPS knew the political pressure originated from Congressman William Harsha's office. Harsha staff members wanted NPS to compromise further so that the retiring congressman could support the Hopeton bill and tell constituents he helped reduce the total acreage. NPS officials asserted the agency had already compromised by its willingness to delete the apartment complex and pursue easements in lieu of fee purchases. NPS would compromise no further because a minimum boundary for preservation purposes had already been defined. [42]

Reducing the amount of farmland taken for Hopeton was precisely what Congressman Harsha intended to do. By May 1980, the House subcommittee added two new potential boundary packages for discussion, one consisting of 150 acres encompassing little beyond the earthworks themselves, the other a slightly larger tract at 320 acres. Fagergren opposed both, stating, "We would be taking the traditional Ohio approach and concentrating on the mounds and earthworks alone, ignoring the village, camp, and other type sites." [43] He favored no less than 450 acres. Harsha's persistent lobbying of the House subcommittee paid off and the 150-acre proposal prevailed with the strong backing of Congressman John Seiberling (Democrat-Ohio). The House of Representatives passed H.R. 3 304-102 on May 20. [44]

Ohio Senator Howard Metzenbaum pledged to shepherd the measure through the Senate and he proved true to his word. By fall 1980, all NPS-related legislation got lumped together into an omnibus national parks bill that became known as the National Park and Recreation Act of 1980. President Jimmy Carter signed Public Law 96-607 on December 28, 1980. Section 701 pertained to expansion of Mound City Group National Monument. For Hopeton Earthworks, a map called "Parcel X," drawn by Harsha's staff, served as the official boundary map. The 1980 law specified that no more than 150 acres could be bought in fee, and "Access to lands in the vicinity of the mounds by existing roadways shall in no way be encumbered by Federal acquisition or administration of the Monument." It also included a one million dollar ceiling for land acquisition and development, archeological studies not to exceed $100,000, and two years to investigate adjacent land to determine their significance to the expanded national monument. [45]

Progress in 1981 and 1982 on acquiring Hopeton Earthworks stalled with the ushering in of President Ronald Reagan's administration. Secretary of the Interior James G. Watt, hostile to further national park system expansion, invoked a land acquisition moratorium and froze further allocations from the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Mound City Group management changed in April as Ken Apschnikat entered on duty as superintendent. Park Service energy expended on Hopeton during these years involved identifying road corridor alternatives to eliminate vehicular routes that bisected Hopeton Earthworks and producing an official 150-acre boundary map. Property owners threatened to stall negotiations for purchase, and take the fight to court, if need be. Conservation organizations like the National Parks and Conservation Association began criticizing James Watt for not proceeding with Hopeton's acquisition. [46]

Lack of progress characterized 1983, too, as the Reagan-Watt land acquisition moratorium continued. In the face of growing criticism, Interior officials mandated that each NPS unit possessing non-federal land within congressionally-authorized boundaries must prepare "land protection plans" (LPP) to replace all existing land acquisition plans. LPPs were to consider the most fiscally-responsible methods for land protection compatible with the purposes for which Congress authorized each park. LPPs would provide landowners and other citizens with the reasoning behind federal intentions for fee simple or other land protection methods.

The massive paperwork exercise began for Mound City Group in March 1983, with a draft LPP produced late in the year. NPS inaction on assessing Hopewellian-related sites and reporting to Congress within two years evoked a critical letter from Ohio State Historic Preservation Officer (SHPO) W. Ray Luce. An inquiry from John Seiberling, House chairman of the Public Lands and National Parks subcommittee, brought the agency's reply that Congress had not authorized nor appropriated funds for such a new area study, and no funding requests would be made until the LPP was approved. By late 1983, however, the Midwest Regional Office determined it would proceed with the "Hopewell Sites Study." [47]

Phase one of the Hopewell Sites Study, an archeological evaluation with recommendations, was awarded under contract to John Blank of Cleveland State University. Blank's findings would serve as the basis of phase two, a feasibility evaluation for adding significant sites. NPS also authorized Blank to include evaluative work at Hopeton, using an emergency grant from the Ohio SHPO. As this effort commenced, news came that American Aggregates Corporation of Greenville, Ohio, commenced negotiations with Hopeton area landowners about sand and gravel mining operations. In June 1984, Ken Apschnikat learned that John Barnhart planned to join with Carmel G. (Bud) Tackett to form the Chief Cornstalk Sand and Gravel Company. Commencing in a gravel pit first used during the Depression, large areas of topsoil were peeled away and a bulldozer began excavating gravel as Barnhart pledged not to mine near the earthworks. By July, the company applied for a mining permit from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Apschnikat began working closely with the SHPO to get the permit denied. He found that no legal avenue existed to halt mining operations from impacting an NHL. Apschnikat nonetheless reported the activity for the 1984 "Threats to the Parks" report for Congress as well as having Hopeton included as a threatened NHL. [48]

Ohio law provided that two hundred tons could be removed without a state permit. SHPO approval no longer was required for such permits, although SHPO staff could be involved in the process to protect the NHL. Estimates on gravel content were as high as a 188-year supply at 150 truckloads per day. By mid-July Apschnikat received the news he dreaded most: with no federal regulation or action in the area to prevent it, Ohio had no other choice but to grant the mining permit. While projected excavations were within the southern boundaries of the NHL, it did not infringe on the parsimonious 150-acres dictated by William Harsha. In the fall, Congressman Bob McEwen, Harsha's successor, inserted one million dollars for Hopeton acquisition in the House's Interior bill, but it failed to clear the Senate. [49]

Dr. John E. Blank completed the first phase of the Hopewell Sites Study in July 1985, identifying more than one hundred sites in Ross County alone. Keeping citizens informed, Blank's study underwent public review. Well-known sites were determined to be significant over other lesser-known sites like villages. To obviate this bias, NPS circulated the report to the professional community and in late 1985, convened a special group hosted by the SHPO to make final site selections to be included in an environmental assessment. The professionals expressed concern that the limited area identified for purchase did not include all of its related archeological resources. Habitation sites on the terraces surrounding the earthworks needed to be preserved and were endangered by gravel quarrying. One expert reported seeing human skeletal remains and post holes in an area exposed by quarrying. [50]

Efforts to secure the one-million-dollar Hopeton acquisition appropriation nearly succeeded in 1985. While McEwen again attached it to the House version, the Senate failed to adopt it. NPS Director William Penn Mott, Jr., lobbied heavily for the funding, and succeeded in getting a half-million-dollars introduced during the conference committee. The funding failed to be included in the bill's final passage at the Christmas recess. Thanks to Mott's personal interest, however, the director pledged to redouble his efforts for fiscal year 1987. [51]

Mott enlisted Howard Metzenbaum and the National Parks and Conservation Association in 1986 to champion Hopeton's acquisition appropriation in the Senate, and by fall, the five-year effort finally succeeded, the result of an exchange of favors between Metzenbaum and Senator James McClure (Republican-Idaho). Much of the year was spent conducting a boundary survey, but the Vaughn family's steadfast refusal to permit entry forced NPS to file a condemnation for right of entry lawsuit. By the end of the year, a draft environmental assessment included six sites for acquisition: Hopeton Earthworks (including additional land beyond 150 acres as well as the quarrying operation), High Banks Works, Hopewell Mound Group, Spruce Hill Works, Seip Earthworks, and Harness Group. For the fifth consecutive year, Hopeton NHL made the endangered landmark list, threatened both by agriculture and gravel quarrying. John Blank added a sense of increased urgency by declaring what remained at Hopeton might be gone in as little as five years. Blank, using aerial photography, satellite imaging, and computer projections, asserted that cultivation had rapidly decimated the earthworks and scant time remained before Hopeton disappeared. The year also proved significant with John Barnhart declaring bankruptcy, then filing an inverse condemnation lawsuit against the federal government, claiming it had restricted his full use and enjoyment of the disputed Hopeton tract. [52]

Even with funding approved for acquisition, prospects for purchasing the 150-acres at Hopeton Earthworks were dim. In January 1987, the U.S. District Court in Columbus ordered the Vaughn family to permit NPS access for a boundary study. Work began on this the following month, and an official appraisal offer went to the Vaughns and Barnhart at summer's end. Both rejected it. As legal troubles already complicated the Barnhart acquisition, the Vaughn negotiation became more problematic upon the death of Gladys Vaughn and uncertain probate issues. In August 1987, phase two of the Hopewell Sites Study, the environmental assessment, went on public review, the results of which urged purchase of more Hopewellian sites.

At this time, the Archaeological Conservancy joined in full partnership with NPS as a key player in preserving significant sites. The Conservancy, led by president Mark Michel, owned ninety acres at Hopewell Mound Group, an interest in High Banks Works, and negotiations were underway to buy Spruce Hill Works. The Archaeological Conservancy and National Parks and Conservation Association stood in the wings, ready to push Congress to add the sites to an enlarged Mound City Group National Monument. Assessing the progress at year's end, Apschnikat recommended that any proposed legislation include a stipulation to rename the NPS unit Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. [53]

Acquisition negotiations continued through 1988 without positive results. In May 1988, Regional Director Don H. Castleberry transmitted the Hopewell Sites Study, mandated by the 1980 Public Law 96-607, to Director Mott. Castleberry recommended four sites be authorized for immediate inclusion with Mound City Group: 224 more acres at Hopeton, High Banks Works, Hopewell Mound Group, and Seip Earthworks. Castleberry deferred inclusion of Spruce Hill Works because of questions raised concerning its Hopewellian origins, and Harness Group was not recommended because of loss of integrity. He called for acquisition, donation, or exchange authority as well as cooperative management flexibility. The Omaha director urged further boundary studies of the four sites to determine that all significant resources were included as well as authority to make minor boundary adjustments up to ten percent of the park unit's total acreage. Castleberry also endorsed the monument's name change and sufficient appropriations, including deleting the parsimonious $100,000 development and research ceiling for Hopeton imposed by Public Law 96-607. Director William Penn Mott, Jr., endorsed the Midwest Regional Office's recommendation in July 1988. [54]

Settlement on the Barnhart tract of 57.87 acres came in late 1988 with a sheriff's sale of the bankrupt property. NPS purchased the Hopeton-related parcel under authority of the 1980 legislation, and was dismayed when another sand and gravel operation acquired the remaining Barnhart interests, including portions within the NHL boundaries. The Hopeton Unit of Mound City Group National Monument became official with the deed filing on January 8, 1990. Under NPS ownership were the southeast corner of the square earthwork wall, and the southwest ends of the parallel walls. Negotiations with the Vaughns continued even as NPS helped draft legislation incorporating the Hopewell Sites Study recommendations. The Archaeological Conservancy pressed NPS to include Cedar Banks and Spruce Hill, once testing proved the latter's authenticity, in the legislative package. Superintendent William Gibson took the recommendation under advisement, seeking input from the Hopewell Sites Study's seventeen original advisors. [55]

|

| Figure 79: View of Hopeton Earthworks looking west. (NPS/ February 1980) |

After a decade of hard work and enduring public skepticism and muted opposition concerning its efforts, the National Park Service's vision of an expanded park became more clear in the public mindset. With the passage of Ronald Reagan's administration to that of George Bush, less dominant and arbitrary policymakers held reign within Interior and expansion of the national park system, while not resuming its earlier frenetic pace, continued with better coordination and far less acrimony. Political support in Congress, bolstered by growing unanimity within the Ohio delegation, flowered as NPS presented convincing data to support its position. While those involved in the Mound City Group National Monument expansion effort experienced considerable frustration during the contentious 1980s, the decade served as a necessary catalyst, permitting Congress to perform an amazing metamorphosis in Ross County, Ohio.

Transformation: Hopewell Culture National Historical Park

While political momentum grew, threats to Hopeton Earthworks NHL continued unabated as the 1990s dawned. Cultivation continued on the disputed Vaughn tract with a condemnation trial set for late summer. Shelly Gravel Company, successor to the bankrupt Chief Cornstalk operation, set up a crusher plant in May 1990 and began excavating within the NHL's western edge. Superintendent William Gibson reported amicable relations with Tim Evans, president of the Thornville, Ohio-based company, and his willingness to avoid known mounds and earthworks inside the NHL boundary. Shelly Gravel, operating under the name Chillicothe Sand and Gravel Company, permitted announced NPS visits onto its property to view operations. One such December visit came as a result of a complaint received at Ohio Historical Society concerning a human burial exposed in one of the gravel pits. An NPS inspection found the area obliterated with no sighting of human bones. Quarrying operations there consumed about eighty square meters of ground per year. [56]

James Ridenour became the third National Park Service director to visit Mound City Group in its history. On his way home to Indiana, Ridenour stopped on June 14, 1990, to view Hopeton and familiarize himself with the area and its issues. While not expressing strong support, Ridenour did nothing to impede or promote progress on Hopeton and the expanded park bill. [57]

Acquisition of Hopeton's remaining 92.13 acres of the authorized 150 came in late September 1990. In a condemnation trial in U.S. District Court with defendants Merrill and Lawrence Vaughn, a federal jury awarded the Vaughns compensation at less than three percent over the government's final offer. NPS took immediate possession of the land, along with the right of access along a farm road. [58]

Prompted by lobbying from the Archaeological Conservancy, Ohio Historical Society, Ohio Archaeological Council, and the Chillicothe-Ross Chamber of Commerce, Howard Metzenbaum announced his intention in September 1990 to sponsor legislation expanding Mound City Group National Monument. Metzenbaum cited his concern for encroaching developments threatening the areas NPS identified for acquisition. One such site, the Hopewell Mound Group, received increased security when the Archaeological Conservancy purchased the railroad right of way adjacent to Anderson Station Road. The purchase blocked potential residential development and preserved Hopewell Mound Group's integrity. [59]

With persistent claims that human bones were being exhumed in the topsoil overburden, a January 9, 1991, onsite meeting at the quarry site took place with Superintendent Gibson, Ohio

Deputy SHPO Franco Ruffini, and Regional Archeologist Mark J. Lynott. They were accompanied by Oliver Collins, member of the Tallige Cherokee Nation and a representative of the Ohio Traditional Indian Rights Council. Unlike the December inspection, pieces of human bone and lithic debris were discovered and given to Oliver Collins for ceremonial reinterment elsewhere. The meeting also produced the startling revelation that spring 1991 quarrying would take place twenty feet away from the NPS boundary. Should quarrying be allowed to progress unchecked, Regional Archeologist Lynott observed that NPS' 150 acres "will be a remnant pedestal surrounded by quarry waste."

Lynott recommended invoking section 9 of the Mining in the National Parks Act of 1976 (Public Law 94-429), with its provisions of notifying Congress and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation of mining threats to national historic landmarks. He also called on NPS to work with the Ohio SHPO to acquire emergency funds for a research program to salvage areas in advance of quarrying to recover archeological information before it could be obliterated. Concurring with Lynott's findings, Midwest Archeological Center manager F. A. Calabrese informed Regional Director Don Castleberry "It is imperative that the Service immediately respond to this threat... [because] a significant part of the NHL will be destroyed in 1991." [60]

Notifying congressional representatives and the Shelly Company of the adverse effect caused by mining, the non-confrontational NPS action and persistent calls for cooperation resulted in such a positive atmosphere that the local newspaper hailed the development. Congressman Bob McEwen pledged his utmost to effect a "reasonable and equitable settlement." A coalition of national conservation organizations stepped up efforts to convince Congress and the Bush administration to use Land and Water Conservation Fund money to purchase the entire Hopeton Earthworks NHL. [61]

On March 21, 1991, Howard Metzenbaum, member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, introduced S. 749, to transform Mound City Group National Monument into Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. The legislation incorporated recommendations of the Hopewell Sites Study, calling for adding 224 more acres to complete Hopeton Earthworks NHL, High Banks Works (190 acres), Hopewell Mound Group (180 acres), and Seip Earthworks (168 acres). Metzenbaum's bill called for further evaluative studies for possible addition of Spruce Hill, Harness Site, and Cedar Banks, as well as "other areas significant to Hopewellian culture." He informed his colleagues of the need for swift action. [62]

Perpetuating the cooperative spirit, a public and private sector meeting in late March 1991 with representatives from NPS, Metzenbaum's office, Ohio Historical Society, and Chillicothe Sand and Gravel reached agreement on salvaging Hopeton artifacts. Volunteer archeologists, working in advance of bulldozers, began finding hearths used for baking food or pottery and other Hopewellian objects. [63]

As gravel quarrying proceeded at full speed, Congressman Bob McEwen introduced a companion House bill to Metzenbaum's S. 749 designated H.R. 2328 on May 14, 1991. A week later, Senate subcommittee hearings began with the most convincing testimony delivered by Mark Michel, president of the Archaeological Conservancy. Michel urged preserving as much as possible of "Prehistoric America's Golden Age," and recommended additional acreage to preserve Hopewell Mound Group and Seip Earthworks, to avoid future Hopeton-like adverse developments. [64]

On July 11, 1991, property estimates for the Hopewell sites developed by the Midwest Regional Office lands division in cooperation with the Trust for Public Land were presented to Congress. Advised of the three-million-dollar pricetag for the combined 762 acres, neither Senate nor House subcommittees took any action before their end-of-summer recess. Chances for early acquisition of one site, the High Banks Works, improved in late July when its owners sold a one-year option to the Archaeological Conservancy. Celebrating all of these positive developments, including the NPS's diamond anniversary, Mound City Group hosted a ceremony dedicating the Hopeton NHL with a plaque and Hopeton Unit's addition to the monument on August 25, complete with a bus tour to the site. [65]

On September 23, the Senate unanimously passed S. 749, and on November 19, the House Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands first held hearings on it. Superintendent William Gibson sat with Director James M. Ridenour as he testified for the Bush administration in favor of both bills. Ridenour informed the subcommittee that the gravel company's self-imposed moratorium on excavating next to the earthworks in the same area where human remains were uncovered had ended in late October. Ridenour stated, "The mined area has been expanded and topsoil is now being stripped off heretofore undisturbed areas that likely may contain additional remains of the Hopewell people and their culture. Without the protection offered by S. 749 the gravel company will destroy the remaining 60% of the Landmark that they currently own." [66]

Weighing in on the quarrying threat and supporting full federal acquisition of Hopeton Earthworks NHL, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation issued a special report per section 9a of Mining in the National Parks Act of 1976. Visiting the site on September 5, the Council made formal recommendations to Interior Secretary Manuel Lujan on November 4. Supporting the bills before Congress, the Council recommended salvage archeology in advance of short-term topsoil stripping, called on NPS to conduct a professional NHL boundary survey, and urged preservation of all historic resources at the site. [67]

While the House subcommittee approved H.R. 2328 in early December, it did not mark up the bill until March 19, 1992. On March 25, the House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee approved it with a voice vote and sent it to the full House of Representatives for consideration. First scheduled for a vote on April 7, H.R. 2328 was pulled from the schedule upon Congressman Bob McEwen's request when he discovered he could not attend. Following the Easter recess, the House took up and passed the measure on May 12. [68]

The final step on the long, tortuous road to add all of Hopeton Earthworks NHL and other related Hopewell culture sites to the national park system came on May 27, 1992. President George Bush signed Public Law 102-294 authorizing Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. Upon Bush's signature, Mound City Group National Monument ceased to exist as a distinct administrative entity. Mound City Group became a unit, like the previously-added 150 acres of Hopeton Earthworks, of the larger national historical park. Hopewell Mound Group, Seip Earthworks, High Banks Works, and additional Hopeton acreage were authorized for acquisition, but the act did not include appropriations to carry out its provisions. Thanks to lobbying by the Archaeological Conservancy's Mark Michel, the act called for further study and consideration for adding Cedar Bank, Spruce Hill, and the Harness Site (Liberty Works). Interest by a southern Indiana congressman resulted in the Mann Site of that state being added to the study list. [69]

Elation over the president's signature creating the expanded national historical park, soon became tempered by political reality, expressed best by Superintendent Bill Gibson: "My real concern was the funding issue, which I knew was the crux of the matter; the mere legislation would be insufficient. In fact, Director Ridenour at one point commented that 'the sites are not preserved because they're not funded,' even though the legislation existed. He had had the experience--and I gained it through this process--to know that having a law on the books that set aside an area is not the same as acquiring and managing it.... I didn't appreciate it at that time because the immediate goal was to get that legislation, and it was wonderful.... [It] turned out you can't do much until you do the acquisition." [70]

|

| Figure 80: At top of this aerial view is Hopeton Earthworks with the immediately adjacent Chillicothe Sand and Gravel Company. (NPS/1993) |

Gravel operations continued during the 1992, and land acquisition negotiations with the gravel company were conducted by the Trust for Public Land. By December, an impasse developed over price. The company's demand for more than $30 million did not come close to the estimates provided to Congress. Trust for Public Land negotiators withdrew, turning the matter back to NPS for resolution. In early January 1993, Superintendent Gibson reported renewed, aggressive quarrying at Hopeton. Heavy equipment moved eastward, toward the NPS boundary. Gibson requested that Omaha officials seek condemnation authority and emergency reprogramming of acquisition funds to halt the gravel quarrying within Hopewell Culture National Historical Park's authorized boundaries. [71]

On February 23, 1993, Acting Assistant Secretary for Policy, Management, and Budget Brad Leonard notified Congress of Interior's intention to file a declaration of taking. The emergency condemnation covered 211.40 acres owned by the Chillicothe Sand and Gravel Company. Leonard argued the measure was the only way to stop the quarrying, estimating that "Approximately 60-70 acres within the park have been stripped and we have no assurance that the destruction will cease." To reimburse the gravel company, up to $1.5 million were reprogrammed from Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia, to cover the costs. [72]

Quarrying at Hopeton during 1993 continued to accelerate as acquisition negotiations intensified. Of the 201 proposed acres, sixty-seven were destroyed by mining, and NPS determined not to purchase those acres, but concentrate on the remaining 134 acres. In the failure of negotiations, the declaration of taking action continued. [73]

Without undergoing legal proceedings in U.S. District Court, settlement came in 1995 as result of the declaration of taking initiative on 134 acres at Hopeton Earthworks. An arbitrator successfully negotiated agreement between NPS and Chillicothe Sand and Gravel Company. Eight acres in agricultural easement also were negotiated for Hopeton, and good progress was made on the Hopewell Mound Group acquisition with the Archaeological Conservancy that same year. [74] In 1996, surveys of three parcels of land totalling ninety-three acres took place to the west and south of Hopewell Mound Group's proposed boundary. Late in the year, surveying along the north boundary began. [75]

Planning for the future of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park includes additional land acquisition, development, and increased staff depending on congressional appropriations. Surely no preservation battle will be as grueling, time-consuming, and resource-degrading as the one fought over Hopeton Earthworks. NPS remains vigilant, having put the public on notice that other significant Hopewellian sites merit concern and preservation.

The National Park Service is programming for and building the fundamental infrastructure needed for an expanded national historical park, utilizing its historic Ross County base at the former Mound City Group National Monument. Facilities reconfiguration of the 1990s, conducted throughout the Mound City Group unit, proved not only excitingly disruptive to NPS staff, but reinforced the concept that times had indeed changed. Working at the Mound City Group unit headquarters was nothing like what it had been in decades past, and certainly the "City of the Dead" during the mid-1990s had found new life, challenge, and excitement. And that is how it should be, as present and future Americans strive to understand the Hopewell culture, by walking amidst ancient monuments.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hocu/adhi/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 04-Dec-2000