|

Hopewell Culture

Amidst Ancient Monuments The Administrative History of Mound City Group National Monument / Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio |

|

CHAPTER EIGHT

Resource Management and Visitor Protection

The natural and cultural resource management functions and visitor protection program grew in a haphazard fashion during the pre-development era of Mound City Group National Monument. Until proper facilities were built and funding became available for professional positions, the monument operated as a "one man show" in the form of Clyde B. King. While King could depend on professional advice and assistance from the Region One Office in Richmond (1946-1955) and Northeast Regional Office in Philadelphia (1955-61), actual permanent staff positions for these program areas did not materialize until after King's departure and the MISSION 66 facility developments were in place and operating. Staff additions came only incrementally. Until the late 1960s, only an archeologist supplemented the permanent staff . The resource management and visitor protection (RM & VP) functions grew slowly, a secondary consideration to the more basic need for interpreters to help educate the visiting public concerning the prehistoric Hopewell culture. In essence, the interpretive program was preeminent in the small park's Division of Interpretation and Resource Management, which took form during the decade of the 1970s.

After Clyde King, most of the men who held the job of superintendent were in the park ranger series and possessed law enforcement certification, a skill that only rarely required active use during any calendar year. Surrounded by larger federal installations with capabilities and personnel in far superior numbers to the small National Park Service unit, national monument managers found having these federal neighbors proved invaluable whenever emergency services were required for visitor protection. Resource management issues were readily identified, but were seldom addressed unless one could no longer be ignored or threatened to impede park operations. For decades the park lacked any formal resource management plan. The first one addressing both cultural and natural resources appeared in 1982. [1]

A 1968 management appraisal of Mound City Group's initial forays into resource management interpretation brought the recommendation to kill it. Citing tight budget and personnel ceilings, Assistant Regional Director George A. Palmer advised the practice of holding late evening programs on the visitor center's patio be discontinued because they attracted only small groups of local residents. He doubted the time and expense of providing such a service could be justified, suggesting instead special open house events be held. Palmer believed other means of engendering local support for the monument should be found. [2]

Park managers ignored Palmer's advice, opting not to cancel the special programs that addressed a variety of topics beyond the immediate Hopewell culture theme. The park possessed an array of resources, and managers felt the programs would help establish an appreciation for their promotion and protection. Such an attitude has prevailed to the present day.

Resource Management Concerns

Following the visitor center's opening in 1960, damaged turf and shrubbery around the building appeared to be caused by burrowing gophers. Superintendent John C. W. Riddle invited two members of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's rodent and predator control unit based in Columbus to visit and advise on this damaged area as well as similar depredations within the mounds enclosure. On October 2, 1962, the experts determined that the omnipresent thirteen-lined ground squirrels were the chief culprits for turf damage, while mice were wreaking havoc on the new shrubbery. Recommended chemical deterrents included calcium cyanide for the ground squirrels and zinc phosphide-treated grain for prairie voles. The rodent control regimen received Washington Office approval, and the first treatments were applied in November 1962. [3]

Controlling the orchard mouse or prairie vole proved difficult. The vegetarian rodents constructed noticeable surface runways through the turf, and frequently availed themselves to tunnels abandoned by ground squirrels. They particularly were fond of seeds and roots and bark of young trees and shrubs, and used burlap from young plantings to construct nests. Monument workers applied zinc phosphide to poison feed grain that was then broadcast to the mounds and along edges of unmowed fields at a rate of six to ten pounds per acre. A January 1963 assessment deemed the poisoning an effective deterrent with reapplication used as conditions warranted.

|

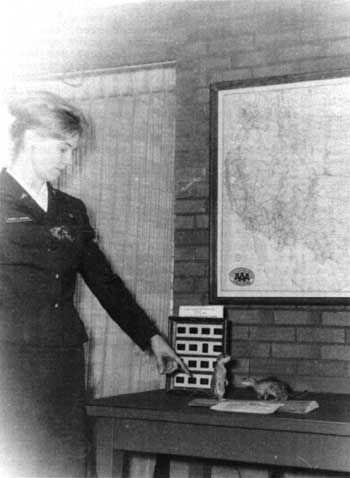

| Figure 71: Park Guide Frances Spetnagel indicates a display on ground squirrels in the visitor center lobby. (NPS/early 1960s) |

Most methods to control ground squirrels at Mound City Group failed. These included using a twenty-two caliber air gun and pumping in water to flood burrow entrances. Although the rodents produced only one litter per year, each litter typically varied from five to fourteen young. If left unchecked, the colony could become very destructive. Application of calcium cyanide using a foot pump duster involved inserting the device into burrow openings and pumping the poison gas into the dens in early spring and late fall, periods of light visitation. While leaving turf areas unsightly, the rodents constituted a real safety hazard as Riddle explained, "They become a nuisance in public use areas by burrowing holes and throwing up small mounds of gravel. This is a hazard to the visitor, as the ground or path that the visitor must walk over to visit the different points of interest become unstabilized and constantly pitted with holes and loose mounds of gravel. The mounds of loose gravel also create a hazard during the periods that the mound area must be mowed." [4]

Superintendent James Coleman made the best of the situation. An avid golfer, Coleman enjoyed practicing his putting upon the lawn of the superintendent's residence. Taking advantage of the ground squirrel holes for making put shots, Coleman sometimes was unable to retrieve his golf balls. After the poison gas regimen was ruled a failure at curbing the ground squirrel population, Coleman authorized purchase of a pellet gun. Concerned by the safety hazard, particularly to small children who enjoyed, despite NPS restrictions, running through the mound area, the staff declared war on the rodents. During one week in March 1966, forty-two ground squirrels were killed as they began emerging from hibernation. Coleman, Maintenance Leader J. Vernon Acton, and Archeologist Lee Hanson took turns using the gun. Hanson later recalled, "We... used to take turns shooting them when there were no visitors around. I thought highly of my marksmanship and did most of the shooting. I found that the ground squirrels had one flaw in their character which was curiosity. I took advantage of this and whenever one would dive into its hole, I would draw a bead on the hole and wait for it to stick its head up to see if I was still there. I got a lot of head shots. We tried to retrieve the carcasses but once in a while one would go down into its burrow and we couldn't reach it." Following a complaint from an irate visitor who viewed one of the poor deceased creatures, the monument put the gun away. [5]

The thirteen-lined ground squirrel issue, and to a lesser extent groundhog burrowing, remains to be solved. Permitting native grass to grow tall has changed the habitat and made it less desirable. Overall numbers of these rodents have decreased. Resource managers continue to seek alternatives to control or remove this exotic species that has few natural predators. New forms of poison gas approved by the Washington Office for rodent control were tried in 1991 by depositing gas cartridges into burrow openings. [6] Such measures have helped keep the nuisance rodent population under control.

Jon Casson, the monument's integrated pest management (IPM) coordinator, prepared a draft IPM plan in 1990. Its primary feature included converting existing turf grasses to native grasses, a radical reversal of past management practices. The plan suggested the same treatment for the Hopeton Earthworks Unit, converting cultivated fields to a mixed native grass species. While the monument lacked sufficient human and fiscal resources to launch its own IPM program, it did engage in cooperating with the U.S. Forest Service to monitor for gypsy moths in the area. By 1990, Mound City Group had six traps installed with negative results. In 1991, it was one of four Midwest parks participating in a regional gypsy moth monitoring program. Chillicothe results were negative until the summer of 1996, when the first specimen appeared in one of seven traps set at Mound City Group. Migrating from northern Ohio, the gypsy moth began to infiltrate the Chillicothe area. [7]

Riverbank erosion became a key issue to be addressed as early as 1977, several years prior to the area of primary erosion being added to the monument. Thirty-five acres of a 52.7-acre tract on the north boundary suffered intensive erosion. Over a fifty-year period, the bank had been worn away an estimated foot per year by the Scioto. The activity threatened to undermine a Hopewell habitation site, and posed an immediate safety hazard to agricultural workers. Park managers needed immediate studies to determine how best to halt the erosion along the large horseshoe river bend as well as learn how mitigative measures might impact private land across the river. That landowner, Bill Houser, had long before contacted the Federal Bureau of Prisons and Chillicothe Correctional Institute (CCI) over the federally-built levee that he contended caused accelerated erosion. Houser's suggestion of a flood channel across CCI land to alleviate potential flooding in north Chillicothe received swift rejection from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, but the opinion was not backed up by research. In early 1983, Ken Apschnikat formally requested the Corps' assistance in developing alternatives for riverbank stabilization. [8]

Erosion-control engineers arrived for an inspection in late March 1983, and it soon became apparent that offering technical assistance under section 55 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1974 might be problematic. Because the legislation lacked language authorizing Corps assistance to another federal agency, the needed assistance had to be postponed for two years in order for the National Park Service to program fiscal resources to reimburse the Corps of Engineers. [9]

Riverbank stabilization work resumed in 1985 with up to $25,000 available for a design analysis of stabilization alternatives and cost estimates, but no full-scale plans and specifications. The Corps' August 1985 study found severe erosion along an eighty-five-foot section of the west bank where piping or surface water leaching off the cultivated field contributed to the accelerated riverbank erosion. To a much lesser extent, erosion caused by high-water events also claimed slough-off. The Corps recommended three courses of action with cost estimates all in excess of $100,000. Because of lack of funds and no visitor use of the area, Superintendent Apschnikat determined to monitor the area every two years and post signs warning people of the dropoff danger. In 1986, two seasonal engineers from the Midwest Regional Office established two monitoring points. These were replaced in 1990 with more accurate fixed datum points to assess the rate and degree of erosion pending construction funds to arrest the problem. [10]

Under provision of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, federal land managing agencies are required to identify all threatened and endangered plants and animals and their critical habitats. National Park Service policy also holds that species considered rare or unique to a park unit be identified and their distribution noted on maps. Federal managers are mandated to protect the species from development or other human-caused harm. While Clyde King prepared lists of plants and animals as early as 1947, no professional survey for threatened and endangered species had been conducted until Ken Apschnikat submitted a funding request in the early 1980s. Resource management experts believed any endangered species would likely exist along the relatively undisturbed Scioto River. In 1987, Apschnikat requested the Natural Areas and Preserves Division of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources to help identify threatened and endangered species that might exist at Mound City Group National Monument. The state findings determined no endangered or rare species within the monument, but four sensitive species known to be in the Chillicothe vicinity. A request for information to be added to a computerized database in 1991 brought the response of lack of staff and funds to compile information on park species. [11]

As the small monument grew beyond the immediate Mound City Group in the early 1990s, it became necessary to expand resources management capabilities in Chillicothe. While still prone to seek expertise at the regional office or closer to home, the park clearly established its need for professional expertise to manage and preserve its increasing number of resources. This professionalization of the staff included for the first time in a quarter-century the addition of an archeologist.

A scoping session to prepare Hopewell Culture National Historical Park's first resource management plan came in November 1993. Hosted by Superintendent Neal and park staff, team specialists included, Associate Regional Director James Loach, Regional Museum Specialist Abby Sue Fisher, Regional Chief of Resource Management Steve Cinnamon, Regional Historian Ron Cockrell, Regional Historical Landscape Architect Mary V. Hughes, and Regional Archeologist Mark J. Lynott. Recognizing the evolving nature of the expanded park, another revision of the key document came in 1995. [12]

Natural resource management in 1995 saw a comprehensive inventory of plants within the five discontiguous units by the National Biological Survey. The agency hired Jennifer Course, a graduate of the University of Wisconsin, to conduct the effort with assistance from volunteers. The team collected 438 species, and found two state-listed species. [13]

Law Enforcement

Simplicity characterized law enforcement activities during Clyde King's superintendency, and he saw fit to solve his most vexing problems by posting a sign stating monument regulations. In May 1947, King reported, "Much of our trouble comes from three sources: picking flowers and damaging trees, the latter to get sticks for use in picnics; using the river bank as a shooting gallery; and driving cars off the roadways as well as operating bicycles on the mounds themselves." For more serious infractions, King sought close ties with the State Highway Patrol as well as the Ross County Sheriff. [14]

King typically found himself acting as a surrogate parent to rowdy and vandal-prone juveniles. In one instance, he had to inform a scoutmaster that the only reason four scouts did not light a fire on the floor of the picnic shelter was because the boys could not get the firewood to ignite. When another boy ignored King's warnings about riding his motor scooter over the earthworks, King's phone call to the boy's father resulted in never seeing the boy or the machine inside the park again. Sometimes King found himself warning adults to behave themselves. One group that used the picnic area every Sunday afternoon in the summer of 1953 became too loud and intoxicated for a public park. King warned them that another infraction would result in their expulsion, and he promised to have State Highway Patrolmen waiting to arrest them for drunk driving. The warning proved a sufficient deterrent. [15]

King's philosophy of always having a uniformed employee visible to the visiting public worked for more than fifteen years. During his tenure, there were no arrests made and vandalism constituted nothing more than carving initials into wooden picnic tables. King's remedy for miscreant carvings was to scour them out as soon as they were discovered in order to discourage other potential vandals. In March 1962, prior to his transfer, King proudly reported that his watchful method worked well, adding that "law violation was at a minimum here where it was almost impossible to hide from the employee on duty, the occupants of the residence, and the twenty-four-hour vigil of the watchtowers of the Federal Reformatory." [16]

On the eve of King's transfer, theft of two audio speakers from atop the visitor center proved an omen of future depredations. Even with the assistance of the local Federal Bureau of Investigation officers to help solve the theft of government property, increasing visitation and expanded park infrastructure foreshadowed more law enforcement incidents. In the absence of adding more staff, park managers had to rely on Clyde King's method as well as assistance from area federal, state, and local law enforcement officers. [17]

Indeed, the monument lacked any formal law enforcement program for another fifteen years. It was not until the late 1970s that a formal program emerged with the requirement that the chief of interpretation and resource management hold a law enforcement commission. It represented the first full-time staff member to hold such a commission beyond the superintendent. Beginning in 1980, law enforcement appeared as a permanent category in the superintendent's annual report. [18]

What made the program possible was the resolution of the thorny issue of jurisdiction. Because the army paid local farmers for Scioto Valley farmland to form the Camp Sherman Reservation in the late 1910s and early 1920s, the federal reserve had exclusive jurisdiction and could rely on only federal law enforcement officers for assistance. The date used for federal acceptance of exclusive jurisdiction for the 67.50 acres of Mound City Group National Monument was December 2, 1919. [19]

In response to recommendations made by the Department of the Interior's Public Land Law Review Commission in 1971, Director George B. Hartzog, Jr., ordered a systemwide review of jurisdictional status and speedy retrocession of jurisdiction. For Mound City Group, the exercise rekindled interest in changing from exclusive to concurrent jurisdiction. [20] The change could not come soon enough for park managers unable to call upon local assistance and frustrated by lack of concern by the U.S. District Court in Columbus. The court refused to adopt a bail forfeiture or collateral system or even process misdemeanor cases. An exasperated Fred Fagergren, Jr., exerting constant pressure on Columbus court officials, exclaimed "[my] staff is placed in the position of being unable to take effective enforcement action itself and being unable to call for local assistance. While the enforcement problem in this area is negligible, we are remiss in not having a truly effective course of action short of arrest." [21]

Fagergren's concerted pressure on U.S. Attorney William Milligan prompted Milligan to present the dilemma to Chief District Judge Timothy Hogan in Cincinnati. Hogan convened a meeting of district judges to discuss the issue and the group, "with some misgivings" to assume the increased workload, agreed in August 1976 to establish a collateral forfeiture system for all federal non-military installations in the Southern District of Ohio. Referred to as the "ticket system" for minor offenses, Judge Hogan called upon each agency to submit a list of offenses and recommended fines for consideration. Omaha officials sent Interior's Twin Cities field solicitor Elmer T. Nitzschke to Cincinnati to assist the court in establishing the new system that went into effect September 1, 1977. [22]

Public Law 94-458, National Park System Improvement in Administration Act of 1976, directed the Secretary of the Interior to standardize disparate jurisdictional issues in the national park system, and to this end the Midwest Regional Office in 1977 sought to obtain concurrent jurisdiction for fourteen parks in six states. Only Mound City Group had exclusive jurisdiction and to retrocede jurisdiction to the state required both congressional and gubernatorial approval. Success finally arrived on November 15, 1982, when Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes signed the document accepting concurrent jurisdiction at Mound City Group National Monument. The action became official upon its recording in Ross County on January 13, 1983. [23]

With the addition of two parcels of excess Department of Justice land in April 1983, the issue of jurisdiction again emerged for the newly-acquired 52.7 acres. Two years later, officials determined the status of the land to be concurrent jurisdiction. With the acquisition of Hopeton Earthworks, Park Service officials in 1987 again had to consider petitioning the state to change jurisdiction for the new additions. [24]

Addition of Hopeton Earthworks also prompted the need for a park radio system for visitor and resource protection. In January 1981, Fagergren initiated steps with the Denver Service Center to get a radio frequency assigned to Mound City Group. Denver officials recommended sharing the same frequency used by Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area in northeast Ohio to promote further cooperation between the two parks. Citing the lack of an effective communications system as a hinderance to efficient management and park operations, Ken Apschnikat listed a radio system in the park's management efficiency standards in 1983. He envisioned the system could be invaluable not only for park operations, but for partnership relations with surrounding agencies, including helping prison and hospital authorities search for escapees and patients, and responding after-hours to visitor center security alarms. [25]

Approval of sharing Cuyahoga Valley's radio frequency came in the fall of 1983, but the equipment was not installed until early spring 1984. With local availability of LEADS service in January 1987, Ross County Sheriff Thomas L. Hamman extended the service as a courtesy to Mound City Group. [26]

In February 1981, the monument prepared its first official policy on commissioned rangers bearing arms. Recognizing the historical reality of few law enforcement cases, officers were not to be routinely armed. Rangers were instead instructed to use their own discretion concerning arms when answering burglar alarms, transporting prisoners, engaging in hunting patrols, or any other instance when physical harm might threaten. Following park expansion in the late 1980s and early 1990s, however, managers recognized the need for at least one additional staff person with a law enforcement commission to address patrolling for Archeological Resources Protection Act violations, poaching, and illicit drug cultivation. The expanded park rendered the radio system nearly obsolete, with a repeater needed for Seip Earthworks and increasing occurrences of receiving Cuyahoga Valley's routine radio traffic. [27]

Because the radio system did not always operate consistently from the new outlying park units, two cellular telephones were acquired in the fall of 1993. The special purchase obviated any disruption in communication during potential emergencies. [28]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hocu/adhi/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 04-Dec-2000