|

Hopewell Culture National Historical Park Ohio |

|

NPS photo | |

Mounds and earthworks along the Scioto River, no doubt the work of many human hands, make us wonder. Who made them? How long have they stood? What role did they play in the lives of their builders?

Beginning in the late 1700s, settlers from the eastern states migrating to the Ohio Valley found hundreds of mounds and earthworks. The Shawnee and other American Indian peoples of the region apparently knew little of the builders. Many tried to solve the mystery of the mounds. Some thought that the moundbuilders must be a "lost race" who vanished before the Indians of historic times arrived.

In the 1840s Ephraim G. Squier, a Chillicothe newspaper editor, and Edwin H. Davis, a Chillicothe physician, systematically mapped the mounds and documented what was found inside them. The Smithsonian Institution published Squier and Davis's findings in the 1848 Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. Through later scientific studies, the "lost race" notion was laid to rest. The Hopewell peoples—American Indians who lived between 2,200 and 1,500 years ago—were recognized as the architects and builders of the mounds.

The Hopewell were named for Capt. Mordecai Hopewell, who owned the farm where part of an extensive earthwork site was excavated in 1891. The Hopewell settled along riverbanks in present-day Ohio and in other regions between the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico. Excavations of dwelling sites show that they made their living by hunting, gathering, gardening, and trading.

No one lived at the earthworks; artifacts found inside reveal that some of the mounds were built primarily to cover burials. A mound was typically built in stages: A wooden structure containing a clay platform was probably the scene of funeral ceremonies and other gatherings. The dead were either cremated or buried on-site. Objects of copper, stone, shell, and bone were placed near the remains. After many such ceremonies the structure was burned or dismantled, and the entire site was covered with a large mound of earth. Wall-like earthworks sometimes surrounded groups of mounds. Squier and Davis named one site Mound City because of its unusual concentration of mounds, at least 23, encircled by a low earthen wall. During World War I Mound City was covered by part of an army training facility, Camp Sherman, and many of the mounds were destroyed. The Ohio Historical and Archaeological Society conducted excavation and restoration work in 1920-21. In 1923 the Mound City Group was declared a national monument.

The National Park Service conducted additional excavations in the 1960s and '70s. In 1992 Mound City Group became Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, which also includes four other sites in the region: High Bank Works, Hopeton Earthworks, Hopewell Mound Group, and Seip Earthworks. As you walk the grounds of Mound City, remember that although we know of the Hopewell peoples primarily through the way they memorialized their dead, their world was very much alive.

The Hopewell World

Imagine Mound City 2,000 years ago: On a midsummer day, young men spear fish while women and children scoop mussels from the riverbank and pick berries. A toolmaker sharpens new flint bladelets. Nearby a potter mixes grit into clay in order to strengthen it for forming into a bowl. An elderly man secures a deerskin cover over a bent-pole structure that serves as a dwelling. Nettle fibers are drying in the sun; they will be twisted into fiber for fabric. Artisans, using copper and mica newly obtained in trade, fashion ornaments for use in a ceremony at the earthworks under construction on the bluffs overhead.

Archeological excavations at Hopewell habitation sites provide a wealth of information about daily life long ago. Middens and trash sites indicate that Hopewell peoples hunted, fished, and gathered wild foods, supplementing their diet with cultivated plants. Patterns of small holes outline the sites of dwellings constructed of bent poles and covered with skins, mats, or bark. Food processing areas marked by large, deep storage pits, earth ovens, and shallow basins are often found outside these structures. Many habitation sites were probably occupied year-round for several years before being vacated when firewood and other local resources ran out.

Scattered groups probably gathered at the major earthwork centers seasonally and for important occasions: feasting, trading, presenting gifts, marriages, competitions, mourning ceremonies, and of course, mound construction. Tools and ornaments used in and worn for these occasions were often made of materials obtained in trade: copper and silver from near the Great Lakes, obsidian (volcanic glass) from a site in present-day Yellowstone National Park, sharks' teeth and seashells from the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico, and mica from the southern Appalachian Mountains. Artisans fashioned these raw materials into fine objects that have been found under the mounds.

By about 1,500 years ago the Hopewell way of life had ended. Within a few hundred years new societies emerged along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. These groups were more fully agricultural and politically more structured. Only the great mounds and earthworks remained as monuments to the once-flourishing Hopewell world.

The Sites of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park

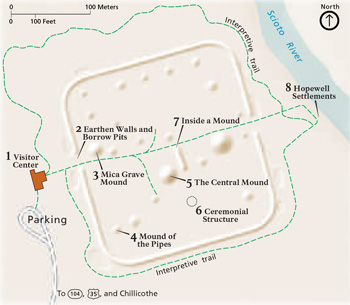

(click for larger map) |

Mound City Group

This ceremonial center consists of 23 mounds that cover the remains of

ceremonial buildings. A low earthen embankment encloses the dense

concentration of mounds. The embankment is ringed by eight sizeable

borrow pits, from which earth was taken for the mounds. A museum inside

the visitor center contains objects recovered from the mounds during two

major archeological digs at the site, including objects made of copper,

flint, mica, and pipestone. An interactive computer kiosk also provides

virtual tours of a wide range of Hopewell sites and topics.

Location: Three miles north of Chillicothe on State

Route 104.

Site Acreage: 120

Hopewell Mound Group

This site includes about three miles of earthen embankments (four to six

feet high in the 1840s); at least 40 mounds, including the largest known

Hopewell mound; and two smaller interior earthworks. It is one of the

largest and most complex Hopewell earthwork centers. The site was named

after the Mordecai Hopewell family, which owned the site in the 1890s

when Warren K. Moorehead conducted excavations here. Sulphur Lick Road

and the Tri-County Triangle bike trail cross this park unit. It is open

year-round.

Location: A few miles west of Chillicothe along

Sulphur Lick Road, near the Intersection with Maple Grove Road. It lies

along the north fork of Paint Creek.

Site Acreage: 316

Seip Earthworks

Seip Earthworks, one of five distinctive tripartite Hopewell earthwork

complexes in the Ross County area, is made up of a large circular

embankment connected to a smaller circle and a square embankment. At

least 18 mounds are found within and around the earthworks, with as many

as 19 interspersed borrow pits. Two mounds, one near the center of the

earthwork, cover the remains of large ceremonial buildings. Nearby are

exhibits and a picnic area. The site is managed in conjunction with the

Ohio Historical Society. It is open year-round.

Location: On U.S. Route 50, 17 miles west of

Chillicothe, between Bourneville and Bainbridge.

Site Acreage: 168

Hopeton Earthworks

Low parallel embankments

of earth nearly 2,500 feet long led up to a set of joined enclosures in

the shape of a large circle and a square. The walls of the square

enclosure were 12 feet tall in the 1840s. Four mounds and several borrow

pits are found along the southern and eastern edges. Two small circular

embankments open onto the area enclosed by the square. It is thought

that this earthwork complex was constructed at a time when use of the

Mound City Group was declining. Site is closed to the public, except

by permit or for special events.

Site Acreage: 292

High Bank Works

This is one of only two Hopewell earthwork complexes known to have an

octagonal enclosure. Eight mounds are found inside the octagon, the

earthen walls of which were 12 A 20-acre circular enclosure is attached

to the northern edge of the octagon by a narrow opening. Large borrow

pits line the edges of the octagon and low, elaborate embankments extend

to the south. This important site is one of the least understood

Hopewell earthworks in Ross County. Site is closed to the public,

except by permit or for special events.

Site Acreage: 190

General Information

Hours and Activities The park visitor center, located at Mound City Group, is on State Route 104, two miles north of U.S. 35 and three miles north of Chillicothe. The visitor center is open seven days a week. It is closed on Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1. Hours are 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. with extended hours in summer. The grounds close at dark.

Mound City has a small picnic area. Food, campgrounds, and lodging are available nearby. Regularly scheduled programs are held throughout the year. For a calendar of events or to receive the park's newsletter, please write to the park or visit our website at www.nps.gov/hocu. Please arrange group tours and school tours in advance of your visit.

For a Safe Visit Watch your children. The Scioto River is swift and deep, so please remain behind the railing. • Poison ivy is plentiful along the trails and in wooded areas. • Watch your footing in grassy areas and do not run. Ground squirrels dig holes that can trip the unwary. • Be alert to changing weather. Thunderstorms are common in spring and summer.

Other Hopewell Sites in Ohio: Mound City is just one of many Hopewell earthwork centers in the Scioto Valley. The Ohio Historical Society maintains a number of these sites. For more information about Ohio Historical Society sites, visit www.ohiohistory.org.

Source: NPS Brochure (2015)

|

Establishment

Hopewell Culture National Historical Park — May 27, 1992 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Pilot Study: 2006 Land Cover Baseline Report for Hopewell Culture National Historic Park NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2014/618 (Jennifer L. Haack-Gaynor, February 2014)

Amidst Ancient Monuments: The Administrative History of Mound City Group National Monument / Hopewell Culture National Historic Park, Ohio (HTML edition) (Ron Cockrell, 1999)

An Evaluation of the Feasibility of Adding Hopeton Earthworks to Mound City Group National Monument (June 1978)

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (E.G. Squier and E.H. Davis, 1848)

Art and Burials in Ancient Ohio: A Tour of the Mound City Necropolis (Eastern National Park & Monument Association, undated)

Bird Community Monitoring at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio: 2005-2007 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2008/101 (David G. Peitz, September 2008)

Bird Community Monitoring at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio: Status Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS-2012/232 (David G. Peitz, January 2012)

Bird Community Monitoring at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio: Status Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS-2015/998 (David G. Peitz, December 2015)

Cultural Landscape Report and Environmental Assessment, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (September 7, 2016)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Hopeton Earthworks, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (1999)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Hopewell Mound Group, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (undated)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Mound City Group, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (1999)

Foundation Document, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio (March 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio January 2017)

General Management Plan, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio (April 1997)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2013/640 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, March 2013)

Guide to Serpent Mound (Emerson F. Greenman, 1964, The Ohio Historical Society)

Historic Structure Report: Carson-Steel Barn, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (February 28, 2025)

Hopewell Airburst

The Hopewell airburst event, 1699-1567 years ago (252-383 CE) (Kenneth Barnett Tankersley, Stephen D. Meyers, Stephanie A. Meyers, James A. Jordon, Louis Herzner, David L. Lentz and Dylan Zedaker, extract from Scientific Reports, 12:1706, February 1, 2022)

Arguments for a comet as cause of the Hopewell airburst are unsubstantiated (Ralph Neuhäuser and Dagmar Neuhäuser, extract from Scientific Reports, 12:12090, July 12, 2022)

Reply to: Arguments for a comet as cause of the Hopewell airburst are unsubstantiated (Kenneth Barnett Tankersley, Stephen D. Meyers, Stephanie A. Meyers and David L. Lentz, extract from Scientific Reports, 12:12113, July 15, 2022)

Refuting the sensational claim of a Hopewell-ending cosmic airburst (Kevin C. Nolan, Andrew Weiland, Bradley T. Lepper, Jennifer Aultman, Laura R. Murphy, Bret J. Ruby, Kevin Schwarz, Matthew Davidson, DeeAnne Wymer, Timothy D. Everhart, Anthony M. Krus and Timothy J. McCoy, extract from Scientific Reports, 13:12910, August 9, 2023)

Hopewell Archeology: The Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley

Volume 7, Number 1 (December 2006) • Volume 7, Number 2 (June 2010)

Volume 6, Number 1 (September 2004) • Volume 6, Number 2 (March 2005)

Volume 5, Number 1 (June 2002) • Volume 5, Number 2 (December 2002)

Volume 4, Number 1 (June 2000) • Volume 4, Number 2 (May 2001)

Volume 3, Number 1 (July 1998) • Volume 3, Number 2 (April 1999)

Volume 2, Number 1 (October 1996) • Volume 2, Number 2 (October 1997)

Volume 1, Number 1 (May 1995) • Volume 1, Number 2 (December 1995)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park: Year 1 (2008) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2008/148 (Craig C. Young, Jennifer L. Haack and Melanie S. Weber, December 2008)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park: Year 2 (2011) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2012/346 (Craig C. Young, Jordan C. Bell, Chad S. Gross and Ashley D. Dunkle, July 2012)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring (Year 3) for Hopewell Culture National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR—2016/1117 (Craig C. Young, Jennifer L. Haack-Gaynor and Jordan C. Bell, January 2016)

Junior Ranger Booklet, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Mound City: The Archaeology of a Renowned Ohio Hopewell Mound Center Midwest Archeological Center Special Report No. 6 (James A. Brown, rev. ed. 2017)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Mound City Group National Monument (David Arbogast and Jill M. York, March 7, 1976, July 1, 1982)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HOCU/NRR-2020/2179 (David S. Jones, Roy Cook, John Sovell, Matt Ley, Hannah Shepler, David Weinzimmer and Carolos Linares, October 2020)

Park Newsletter (The Falcon): Fall/Winter 1996-1997

Park Newspaper (Hopewell Happenings): 2006 • 2007 • 2008 • 2009 • 2011 • 2014

People Who Came Before: The Hopewell Culture Curriculum Guide (Rebecca Jones, Anne Gibson, Cathy Nelson and Mecca Caron, 1999)

Preliminary Report: The Hopeton Earthworks (1964)

Resource Briefs

2012 Breeding Bird Survey Results for Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio (David G. Peitz, undated)

2013 Breeding Bird Survey Results for Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio (David G. Peitz, undated)

2016 Monitoring Summary for Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio (David G. Peitz, undated)

Bird Monitoring at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (2012)

Bird Monitoring at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio (March 10, 2017)

Climate, Trees, Pests, and Weeds: Change, Uncertainty, and Biotic Stressors in Eastern National Park Forests (January 20, 2015)

Climate, Trees, Pests, and Weeds: Change, Uncertainty, and Biotic Stressors in Eastern National Park Forests (January 29, 2015)

Hopewell Culture National Historical Park: How might future warming alter visitation? (June 21, 2015)

Night Skies and Photic Environment (2014)

Recent Climate Change Exposure of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (July 31, 2014)

Results of the 2014 Birding Efforts at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio (David W. Londe, undated)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio: Project Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HOCU/NRR—2014/793 (David D. Diamond, Lee F. Elliott, Michael D. DeBacker, Kevin M. James, Dyanna L. Pursell, Alicia Struckhoff, April 2014)

hocu/index.htm

Last Updated: 15-Apr-2025